In early December 2021, a new ransomware actor started advertising its services on a Russian underground forum. They presented themselves as ALPHV, a new generation Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) group. Shortly afterwards, they dialed up their activity, infecting numerous corporate victims around the world. The group is also known as BlackCat.

One of the biggest differences from other ransomware actors is that BlackCat malware is written in Rust, which is unusual for malware developers. Their infrastructure websites are also developed differently from other ransomware groups. Due to Rust’s advanced cross-compilation capabilities, both Windows and Linux samples appear in the wild. In other words, BlackCat has introduced incremental advances and a shift in technologies to address the challenges of ransomware development.

The actor portrays itself as a successor to notorious ransomware groups like BlackMatter and REvil. The cybercriminals claim they have addressed all the mistakes and problems in ransomware development and created the perfect product in terms of coding and infrastructure. However, some researchers see the group not only as the successors to the BlackMatter and REvil groups, but as a complete rebranding. Our telemetry suggests that at least some members of the new BlackCat group have links to the BlackMatter group, because they modified and reused a custom exfiltration tool we call Fendr and which has only been observed in BlackMatter activity.

This use of a modified Fendr, also known as ExMatter, represents a new data point connecting BlackCat with past BlackMatter activity. The group attempted to deploy the malware extensively within organizations in December 2021 and January 2022. BlackMatter prioritized collection of sensitive information with Fendr to successfully support their scheme of double coercion. In addition, the modification of this reused tool demonstrates a more sophisticated planning and development regimen for adapting requirements to target environments, characteristic of a maturing criminal enterprise.

Two incidents of special interest

Two recent BlackCat incidents stand out as particularly interesting. One demonstrates the risk presented by shared cloud hosting resources, and the other demonstrates an agile approach to customized malware re-use across BlackMatter and BlackCat activity.

In the first case, it appears the ransomware group penetrated a vulnerable ERP provider in the Middle East hosting multiple sites. The attackers delivered two different executables simultaneously to the same physical server, targeting two different organizations virtually hosted there. The initial access was mistaken by the attackers for two different physical systems and drives to infect and encrypt. The kill chain was triggered prior to the “pre-encryption” activity, but the real point of interest here lies in the shared vulnerabilities and thedemonstrable risk of shared assets across cloud resources. At the same time, the group also delivered a Mimikatz batch file along with executables and Nirsoft network password recovery utilities. In a similar incident dating back to 2019, REvil, a predecessor of BlackMatter, appears to have penetrated a cloud service supporting a large number of dental offices in the US. Perhaps this same affiliate has reverted to some old tactics.

The second case involves an oil, gas, mining and construction company in South America. This related incident further connects BlackMatter ransomware activity with BlackCat. Not only did the affiliate behind this ransomware incident attempt to deliver BlackCat ransomware within the target network, but approximately 1 hour 40 minutes before its delivery they installed a modified custom exfiltration utility that we call Fendr. Also known as ExMatter, this utility had previously been used exclusively in BlackMatter ransomware activity.

Here, we can see that the BlackCat group increased the number of file extensions for automatic collection and exfiltration by the tool:

| Fendr file extensions (17146b91dfe7f3760107f8bc35f4fd71) | |||||

| .doc | .docx | .xls | .xlsx | .xlsm | |

| .msg | .ppt | .pptx | .sda | .sdm | .sdw |

| .zip | .json | .config | .ts | .cs | .sqlite |

| .aspx | .pst | .rdp | .accdb | .catpart | .catproduct |

| .catdrawing | .3ds | .dwt | .dxf | .csv | |

These additional file extensions are used in industrial design applications, like CAD drawings and some databases, as well as RDP configuration settings, making the tool more customized towards the industrial environments that we see being targeted by this group. And, if we believe the PE header timestamp, the group compiled this Fendr modification just a few hours before its initial use. One of the organizations targeted with the Fendr exfiltration tool has branches all over the world, resulting in a surprising mix of locations. Not all of the systems received a ransomware executable.

Technical details

| MD5 | B6B9D449C9416ABF96D21B356A41A28E |

| SHA1 | 38fa2979382615bbee32d1f58295447c33ca4316 |

| SHA256 | be8c5d07ab6e39db28c40db20a32f47a97b7ec9f26c9003f9101a154a5a98486 |

| Compiler | Rust |

| Filesize | 2.94 MB |

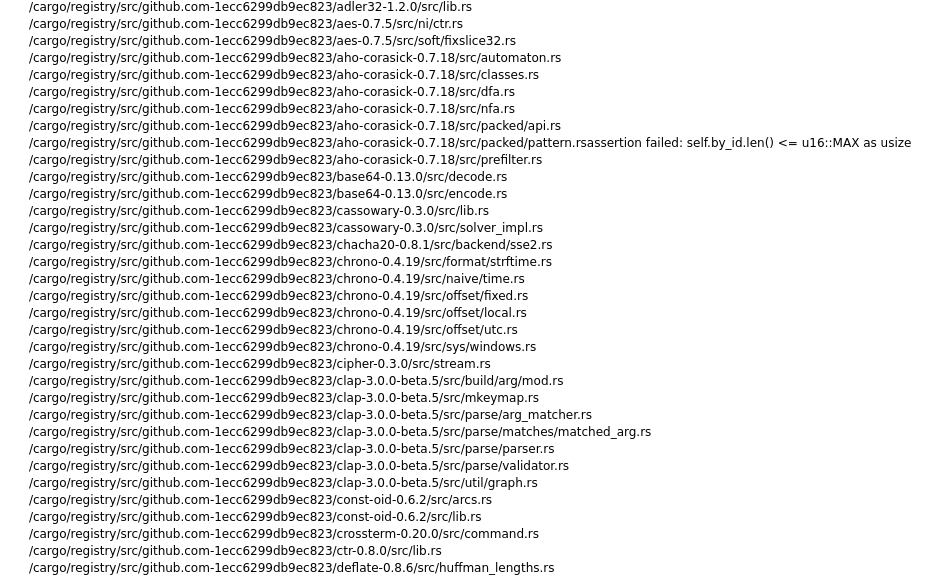

The analyzed BlackCat ransomware file “<xxx>_alpha_x86_32_windows_encrypt_app.exe” is a 32-bit Windows executable file that was coded in Rust. The resulting Rust compiled binaries use the Rust standard library with a lot of safety checks, memory allocations, string processing, and other operations. They also include various external crates with libraries for required functionality, like Base64, AES encryption, etc. This particular language, and its compilation overhead, makes disassembly analysis more complicated. However, with the proper approach and Rust STD function signatures applied in IDA (or your disassembler of choice, for example Ghidra), it’s possible to understand the full malware capabilities with static analysis. Additional Rust library usage can be obtained from strings in clear form as no obfuscation is whatsoever used by the malware:

External cargo is used in malware

Rust is a cross-compilation language, so a number of BlackCat Linux samples quickly appeared in the wild shortly after their Windows counterparts.

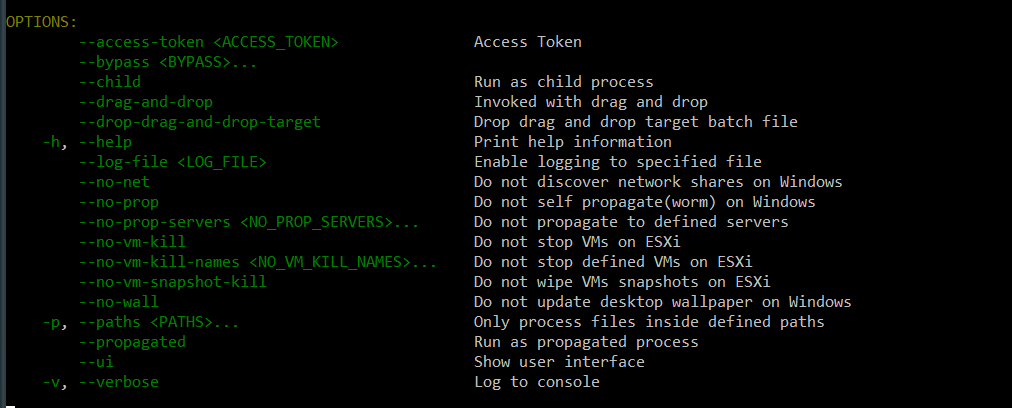

This BlackCat sample is a command line application. After execution, it checks the command line arguments provided:

Command line arguments for malware

BlackCat is an affiliate actor. This means it provides infrastructure, malware samples, ransom negotiations, and probably cash-out. Anyone who already has access to compromised environments can use BlackCat’s samples to infect a target. And a little help with ransomware execution is likely to come in handy.

The command line arguments are pretty self-explanatory. Some are related to VM’s, such as wiping or not wiping VM snapshots or stopping VM on ESXi. Also, it’s possible to select specific file folders to process or execute malware as a child process.

Shortly after execution, the malware gets the “MachineGuid” from the corresponding Windows registry key:

This GUID will be used later in the encryption key generation process.

The malware then gets a unique machine identifier (UUID) using a WMIC query executed as a separate command by creating a new cmd.exe process:

This UUID is used together with the “–access-token” command-line argument to generate a unique ACCESS_KEY for victim identification.

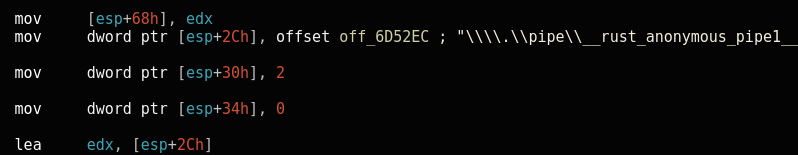

BlackCat ransomware uses Windows named pipes for inter-process communication. For example, data returned by the cmd.exe process will be written into named pipes and later processed by malware:

The names of the pipes are not unique and are hard-coded into malicious samples.

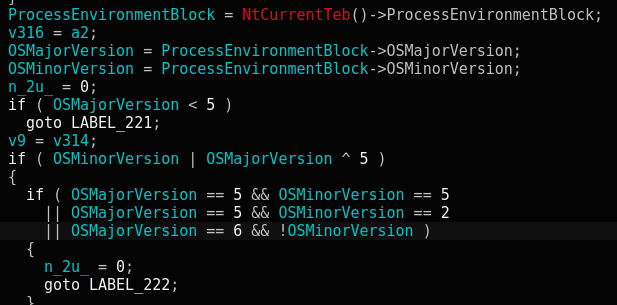

The malware checks which version of the Windows operating system it’s being executed under. That is done using the fairly standard technique of getting this information from the Process Environment Block structure:

The operating system version is required to implement a proper Privilege Escalation technique such as:

- Simple process token impersonation

- COM elevation moniker UAC Bypass

The malware uses a previously known technique, used by LockBit ransomware, for example, to exploit an undocumented COM object (3E5FC7F9-9A51-4367-9063-A120244FBEC7). It is vulnerable to the CMSTPLUA UAC bypass.

Using “cmd.exe” malware executes a special command:

fsutil behavior set SymlinkEvaluation R2L:1 |

This command adjusts the behavior of the Windows file system symlinks. It allows the malware to follow shortcuts with remote paths.

Another command executed as part of pre-encryption is:

vssadmin.exe delete shadows /all /quiet |

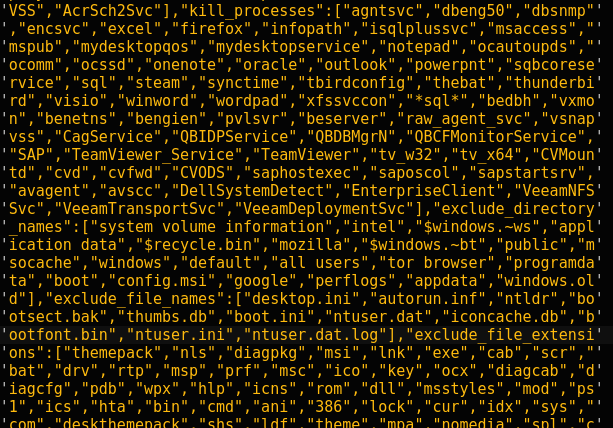

This is almost standard for any ransomware and deletes all Windows shadow copy backups. Then the malware gets a list of services to be killed, as well as files and folders to be excluded from the encryption process, kills processes and starts encryption using separate working threads:

Embedded process list to kill

This particular sample was observed to be run with “–access-token xxx –no-prop-servers \\xxx –propagated” command line parameters. In addition to the activity detailed above, the malware will attempt to propagate, but will not re-infect the server that it is attempting to run on. It will perform a hard stop on any IIS services hosted on the system with “iisreset.exe /stop”, check the local area network for immediately reachable systems with “arp -a”, and increase the upper limit on the number of concurrent commands that can be outstanding between a client and a server by increasing the MaxMpxCt to the maximum allowed with:

cmd /c reg add HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\LanmanServer\Parameters /v MaxMpxCt /d 65535 /t REG_DWORD /f |

Also, it is notable that the group uses a compressed version of PsExec to spread laterally within an organization, as was observed with the remote execution of this sample.

The malware appends an extension to the encrypted files, but the exact extension varies from sample to sample. The extension can be found hard-coded in the malware’s JSON formatted configuration file.

For encryption, the malware used the standard “BCryptGenRandom” Windows API function to generate encryption keys. AES or CHACHA20 algorithms are used for file encryption. The global public key that is used to encrypt local keys is extracted from the configuration file.

Most of these executables maintain a hard-coded set of username/password combinations that were stolen earlier from the victim organization for use during propagation and privilege escalation. There often appears to be almost half a dozen accounts, and a combination of domain administrative and service level credentials. This means the individual executable is compiled specifically for the target organization, containing sensitive information about the organization.

After the encryption process, the malware drops a ransomware note with details on how to contact the BlackCat ransomware operators.

Conclusion

After the REvil and BlackMatter groups shut down their operations, it was only a matter of time before another ransomware group took over the niche. Knowledge of malware development, a new written-from-scratch sample in an unusual programming language, and experience in maintaining infrastructure is turning the BlackCat group into a major player on the ransomware market.

Here we present a new data point connecting BlackCat with past BlackMatter activity – the reuse of the exfiltration malware Fendr. The group modified the malware for a new set of victims collected from data stores commonly seen in industrial network environments. BlackCat attempted to deploy the malware extensively within at least two organizations in December 2021 and January 2022. In the past, BlackMatter prioritized collection of sensitive information with Fendr to successfully support their double coercion scheme, just as BlackCat is now doing, and it demonstrates a practical but brazen example of malware re-use to execute their multi-layered blackmail. The modification of this reused tool demonstrates a more sophisticated planning and development regimen for adapting requirements to target environments, characteristic of a more effective and experienced criminal program.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh