![]() The state of stalkerware in 2021 (PDF)

The state of stalkerware in 2021 (PDF)

Main findings of 2021

Every year Kaspersky analyzes the use of stalkerware around the world to better understand the threat it poses. We partner with stakeholders across public and private sectors to raise awareness and find solutions to best tackle this important issue.

Stalkerware enables people to secretly spy on other people’s private lives via smart devices and is often used to facilitate psychological and physical violence against intimate partners. The software is commercially available and can access an array of personal data, including device location, browser history, text messages, social media chats, photos and more. The marketing of stalkerware is not illegal, but its use without the victim’s consent is. Perpetrators benefit from this vague legal framework that still exists in many countries. Stalkerware is a breach of privacy and a form of tech abuse. To address this complex threat in a comprehensive way that best supports victims and survivors, innovative tools from a legislative, social and technological point of view are needed.

2021 data highlights

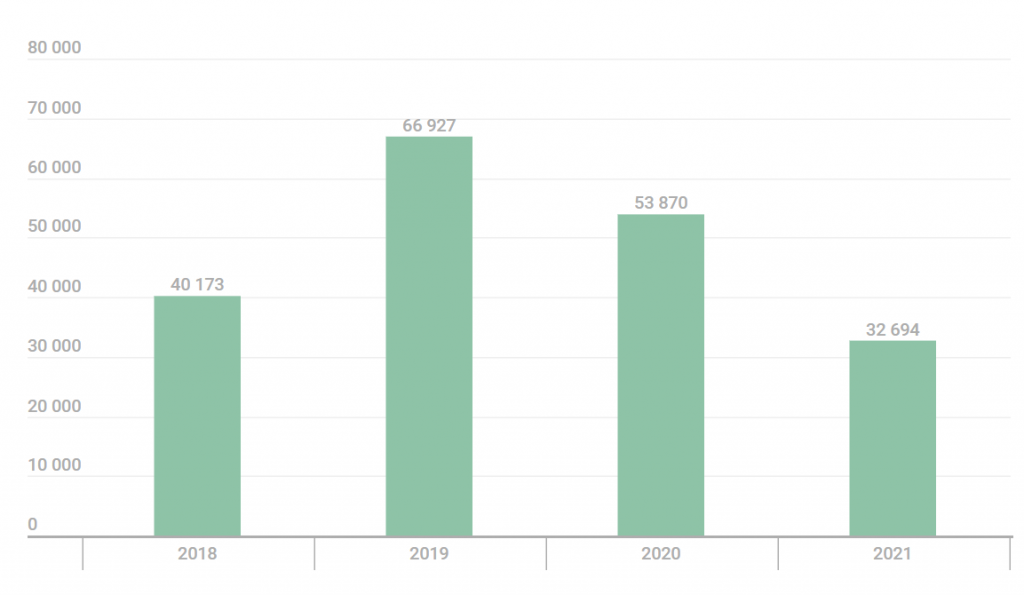

- In 2021, Kaspersky’s data shows that 32,694 unique users were affected by stalkerware globally. This is a decrease from our 2020 numbers and a historic low since we first started gathering data on stalkerware in 2018. While this could be seen as a reason for celebration, it is not.

- Cyber-violence is on the rise, especially since the beginning of the pandemic. As people have continued to socialize less and spend more time at home, perpetrators feel more in control, possibly making them less prone to installing stalkerware to spy on their partner. In addition, abusers, unfortunately, have a wider range of means, in the form of smart devices, to spy on or stalk their victims. Non-profit organizations (NPOs) with which Kaspersky works closely have shared similar observations from working with perpetrators and victims of stakerware. It is important to remember that these numbers only include Kaspersky users: they do not take into account users who use the IT security solutions of our competitors or those who do not have any IT security solutions installed on their mobiles. Therefore, we see only the tip of the iceberg: while it is difficult to calculate the exact number of affected users in the world, members from the Coalition against Stalkerware estimate that it could be at least 30 times higher, with close to one million victims globally, each year.

- Based on data obtained from the Kaspersky Security Network, the most affected countries remain Russia, Brazil and the United States. This is in line with statistics from the past two years. At the regional level, we find the highest numbers of affected users in:

- Germany, Italy and the UK (Europe)

- Turkey, Egypt and Saudi Arabia (Middle East and Africa)

- India, Indonesia and Vietnam (Asia-Pacific)

- Brazil, Mexico and Columbia (Latin America)

- The United States (North America)

- The Russian Federation, Ukraine and Kazakhstan (Russia and Central Asia)

- Cerberus and Reptilicus were the most used stalkerware applications, with 5,575 and 4,417 affected users, respectively, globally.

Trends observed by Kaspersky

Methodology

The data in this report has been taken from aggregated threat statistics obtained from the Kaspersky Security Network. The Kaspersky Security Network is dedicated to processing cybersecurity-related data streams from millions of volunteer participants around the world. All received data is anonymized. To calculate our statistics, we review the consumer line of Kaspersky’s mobile security solutions applying only the Coalition Against Stalkerware’s detection criteria on stalkerware. This means that the affected number of users were targeted by stalkerware only. Other types of monitoring or spyware apps that fall outside of the Coalition’s definition are not included in our statistics.

The statistics reflect unique mobile users affected by stalkerware: this is different from the number of detections. The number of detections can be higher as we may detect stalkerware several times on the same device of the same unique user if they decided not to remove the app after receiving our notification.

Finally, the statistics reflect only mobile users using Kaspersky’s IT security solutions. Some users may use another cybersecurity solution on their devices, while some do not use any solution at all.

Global detection figures: affected users

In this section, we highlight the global and regional numbers observed by Kaspersky in 2021 and how they compare with those from previous years.

In 2021, a total of 32,694 single users were affected by stalkerware. The graphic below shows the evolution of affected users year on year since 2018.

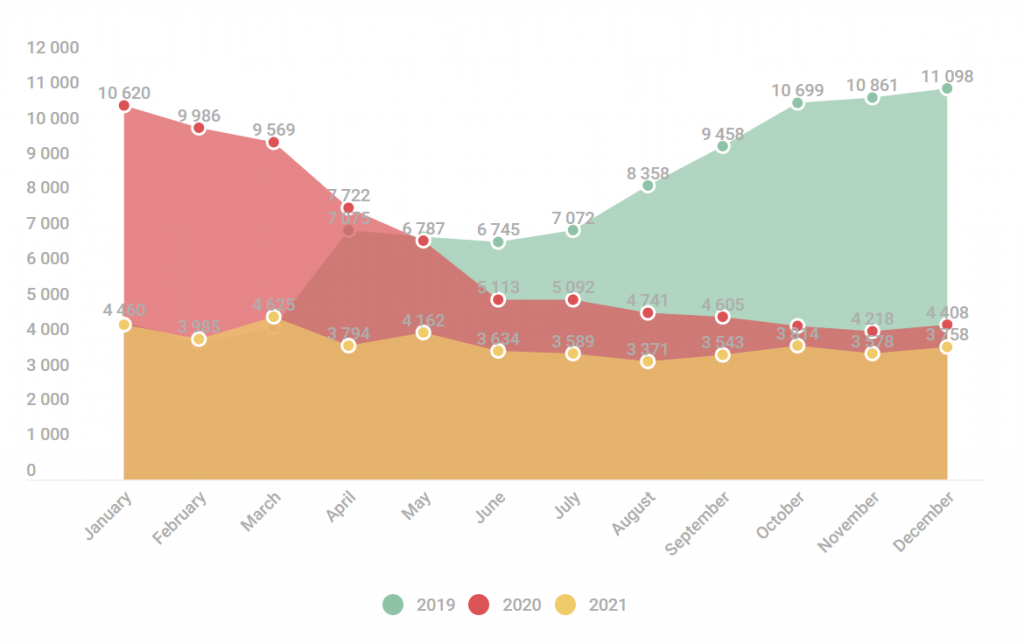

The graphic below shows unique affected users per month over the 2019-2021 period. We can see that in 2021 the trend was more stable than in 2020, which saw a visible decrease during the months most impacted by lockdowns and quarantine measures.

Global and regional detection figures: geography of affected users

Stalkerware continues to affect people across the world: in 2021, Kaspersky detected affected users in 185 countries or territories.

As in 2020, Russia, Brazil, the United States and India are, again, the top four countries with the most identified single affected users. Interestingly, Mexico has fallen from fifth to ninth place and Algeria, Turkey and Egypt have entered the top 10. They have replaced Italy, the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia, which are no longer in the top 10 countries most affected by stalkerware.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 7541 |

| 2 | Brazil | 4807 |

| 3 | United States of America | 2319 |

| 4 | India | 2105 |

| 5 | Germany | 1012 |

| 6 | Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 891 |

| 7 | Algeria | 665 |

| 8 | Turkey | 660 |

| 9 | Mexico | 657 |

| 10 | Egypt | 640 |

Table 1 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – globally

In this year’s report, we provide more detailed regional statistics with numbers for Europe, Asia-Pacific, Latin America, North America, Russia and Central Asia and the Middle East and Africa.

In Europe, the total number of single affected users was 4,236 in 2021. Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom rank at the top of the list, repeating their top rankings last year. Austria has been replaced in the top 10 by Czechia.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | Germany | 1012 |

| 2 | Italy | 611 |

| 3 | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | 430 |

| 4 | France | 410 |

| 5 | Poland | 321 |

| 6 | Spain | 321 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 165 |

| 8 | Romania | 125 |

| 9 | Belgium | 94 |

| 10 | Czechia | 82 |

Table 2 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – Europe

In Russia and Central Asia, the total number of single affected users was 9,207. The top three countries were Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 7541 |

| 2 | Ukraine | 490 |

| 3 | Kazakhstan | 461 |

| 4 | Belarus | 250 |

| 5 | Uzbekistan | 223 |

| 6 | Azerbaijan | 92 |

| 7 | Republic of Moldova | 51 |

| 8 | Tajikistan | 49 |

| 9 | Kyrgyzstan | 40 |

| 10 | Turkmenistan | 19 |

Table 3 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – Russia and Central Asia

In the Middle East and Africa region, the total number of affected users in the entire region was 6,270 with Turkey, Egypt and Saudi Arabia having the most affected users.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | Turkey | 660 |

| 2 | Egypt | 640 |

| 3 | Saudi Arabia | 575 |

| 4 | Kenya | 271 |

| 5 | South Africa | 240 |

| 6 | United Arab Emirates | 143 |

| 7 | Nigeria | 123 |

| 8 | Kuwait | 68 |

| 9 | Oman | 58 |

| 10 | Ethiopia | 46 |

Table 4 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – META

In APAC, the total number of affected users was 4,243. India was substantially ahead of other countries with 2,105 single users affected. It was followed by Indonesia and Vietnam.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | India | 2105 |

| 2 | Indonesia | 353 |

| 3 | Vietnam | 258 |

| 4 | Philippines | 240 |

| 5 | Malaysia | 229 |

| 6 | Australia | 205 |

| 7 | Bangladesh | 169 |

| 8 | Japan | 167 |

| 9 | Pakistan | 98 |

| 10 | Sri Lanka | 83 |

Table 5 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – Asia Pacific

The Latin America and Caribbean region ranking was dominated by one country: Brazil, which represented 72.5% of the total number of affected users in the region (and accounts for roughly 32% of the region’s population). Brazil was followed by Mexico and Colombia. The entire region had 6,609 affected users.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | Brazil | 4807 |

| 2 | Mexico | 657 |

| 3 | Colombia | 202 |

| 4 | Ecuador | 192 |

| 5 | Peru | 179 |

| 6 | Argentina | 90 |

| 7 | Chile | 73 |

| 8 | Venezuela | 58 |

| 9 | Bolivia | 46 |

| 10 | Haiti | 36 |

Table 6 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – Latin America

Finally, in North America, the United States accounted for 87% of all affected users in the region, which was expected given that its population is ten times larger than that of Canada. The total number of affected users in North America, excluding Mexico which has been included with the Latin America data, is 2,666.

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | United States of America | 2319 |

| 2 | Canada | 347 |

Table 7 – 2021’s top 10 countries affected by stalkerware – North America

Common functionalities of stalkerware applications

This section lists the stalkerware applications that are the most used to control mobile devices on a global level. Cerberus and Reptilicus were the most used stalkerware applications with 5,575 and 4,417 affected users, respectively, globally.

| Application name | Affected users | |

| 1 | Cerberus | 5,575 |

| 2 | Reptilicus (aka Vkurse) | 4,417 |

| 3 | Track My Phones | 1,919 |

| 4 | AndroidLost | 1,731 |

| 5 | MobileTracker Free | 1670 |

| 6 | Hoverwatch | 1,094 |

| 7 | wSpy | 1,050 |

Table 8 – 2021’s top list of stalkerware applications

Stalkerware applications can give tremendous power and access to its users, depending on the applications and whether they are used in free or paying mode. Some of them are marketed as anti-theft or parental control applications, however, they are different in many ways, beginning with the fact that they work in stealth mode without the consent and knowledge of the victim.

Most of the popular applications provide common stalkerware functionality such as:

- Hiding app icon

- Reading SMS, MMS and call logs

- Getting lists of contacts

- Tracking GPS location

- Tracking calendar events

- Reading messages from popular messenger services and social networks, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, Viber, Instagram, Skype, Hangouts, Line, Kik, WeChat, Tinder, IMO, Gmail, Tango, SnapChat, Hike, TikTok, Kwai, Badoo, BBM, TextMe, Tumblr, Weico, Reddit etc.

- Viewing photos and pictures from phones’ image galleries

- Taking screenshots

- Taking front (selfie-mode) camera photos

Are Android OS and iOS equally affected by stalkerware?

Stalkerware tools are less frequent on iPhones than Android devices because iOS is traditionally a closed system. However, perpetrators can work around this limitation on jailbroken iPhones, but they still require direct physical access to the phone to jailbreak it. iPhone users who fear surveillance should always keep an eye on their device.

Alternatively, an abuser can offer their victim an iPhone – or any other device – with pre-installed stalkerware. There are many companies that make these services available online, allowing abusers to have these tools installed on new phones, which can then be delivered in factory packaging under the guise of a gift to the intended victim.

The use of stalkerware may be decreasing, but violence is not

While we observe a decrease of 39% of affected users from our 2020 data, the fight against stalkerware and against cyber violence is far from over. The number of affected users and some of the behaviors and perceptions around the use of stalkerware are still concerning. In November 2021, Kaspersky commissioned a global survey of more than 21,000 participants in 21 countries on their attitudes towards privacy and digital stalking in intimate relationships. While the majority of respondents (70%) do not believe it is acceptable to monitor their partner without consent, a significant share of people (30%) doesn’t see any issue with it and find it acceptable under certain circumstances. Of those who think there are justifiable reasons for secret surveillance, almost two thirds would engage in the behavior if they believed their partner was being unfaithful (64%) or if it was related to their safety (63%) and half would if they believed their partner was involved in criminal activities (50%).

High-speed internet in conjunction with the rapid spread of information and communication technology (ICT) has supported cyber-violence by creating another tool for abusers to share violent and dangerous materials or engage in behaviors that affect emotional, psychological or physical damage. While these technologies have given people the ability to maintain social and emotional relationships across wide-ranging physical distances, ICT has also enabled cyber-violence – a consequence that’s far-reaching effects extend to the offline world with real-life negative impacts on its victims.

The results of our survey corroborate this, with 15% of respondents worldwide being required by their partner to install a monitoring app and 34% of those also experiencing physical and/or verbal abuse by that intimate partner.

While it is too early to make definitive conclusions on the decrease of affected users in 2021, there are two theories that could explain this trend.

Firstly, we believe that all aspects of our lives are still heavily impacted by the pandemic. Recent studies[1] show that new behaviors are emerging across areas of life such as work, learning, home, consumption, communications and information, travel and mobility. In short, people are staying at home more (49% avoid leaving their homes and 50% are working from home partially or entirely), reducing face to face interactions (57% indicate that they are socially distancing from friends and the community) and traveling, and shopping, educating and entertaining themselves increasingly online. From an abuser’s point of view, this could result in less need to spy on their partner, who is now in their sight most of the time.

Secondly, the Internet of Things (IoT) and digitization are now everywhere in our lives. It fills our daily routines and our homes, cars and offices. While the opportunities and advantages are endless, many devices also enable tracking by third parties. Our research suggests that perpetrators might also use other means, aside from stalkerware, to track their partners, with 50% of respondents to our survey indicating that they have been tracked through phone apps, another 29% mentioning they had been traced through tracking devices, 22% through webcams and 18% through smart home devices.

Apple’s recent January 2022 publication of a safety manual for its AirTag product marks a shift in the perception of the situation.

NNEDV, the National Network to End Domestic Violence and WWP EN, the European Network for the Work with Perpetrators of Domestic Violence share with us their experience and views on these two theories and on tech abuse in general.

How measures imposed by governments during the pandemic facilitated and reinforced perpetrators’ coercive control – Berta Vall Castelló, Research and Development manager and Anna McKenzie, Communications manager at WWP EN

The European Network for the Work With Perpetrators of domestic violence (WWP EN) is a membership association of organisations directly or indirectly working with people who perpetrate violence in close relationships. The main focus of WWP EN is violence perpetrated by men against women and children. The mission of WWP EN is to improve the safety of women and their children and others at risk from violence in close relationships, through the promotion of effective work with those who perpetrate this violence, mainly men.

Coercive control is defined as “a pattern of abusive behavior designed to exercise domination and control over the other party to a relationship. It can include a range of abusive behaviors – physical, psychological, emotional or financial – the cumulative effect of which over time robs victim-survivors of their autonomy and independence as an individual” (McGorrery and McMahon, 2020). As we write in our manual “Same Violence, New Tools – How to work with violent men who use cyberviolence,” perpetrators isolate their partners and make them emotionally dependent. They use assaults, threats, intimidation, humiliation, isolation and more to create a constant sense of fear, as well as a general loss of a sense of freedom. ICT technologies are powerful tools for perpetrators exerting coercive control, especially in relationships where violence is already present offline.

A recent review on domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic found that the measures imposed by the government during lockdown facilitate and reinforce perpetrators’ coercive control. The authors suggested that the conditions of isolation/physical distancing imposed by the governments overlap with coercive control strategies used by perpetrators to control their partners (Pentaraki and Speake, 2020). Considering these results, it seems likely that perpetrators feel less of a “need” to use stalkerware to exert coercive control over their partners. Moreover, recent research has observed that technology-facilitated abuse often escalates during a period of separation (George and Harris 2014; Woodlock 2016). Therefore, during a lockdown situation where couples were forced to stay together at home, they are less likely to use technology-facilitated abuse.

We must remember that a decrease in the use of stalkerware does not equal a decrease in overall intimate partner violence (IPV) during the pandemic. On the contrary, Boxall, Morgan and Brown (2020) note that IPV has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the results in this report indicate that stalkerware has been replaced with other tools. As Elena Gajotto, from Italian NGO Una Casa per l’Uomo, remarks: “It is so easy to monitor and track someone, for example by using their Google account, that you don’t really need to use stalkerware.” The wide variety of possible technology-facilitated abuse might have had an impact on the decrease in the use of stalkerware specifically. Letizia Baroncelli, from Italian NGO Centro Ascolto Uomini Malttratanti (CAM), agrees and adds: “I think we see less stalkerware because there are so many other forms of perpetrating digital abuse.”

However, NGOs, governments and researchers have reported a substantial increase in image-based abuse and sextortion since the start of the pandemic (Boniello, 2020; CCRI, personal communication, June 2, 2020; FBI, 2020, 2021). It seems that this type of technology-facilitated abuse has escalated, especially among teenagers and couples who do not live together. As Letizia Baroncelli notes: “Sharing personal pictures has increased a lot since the pandemic, especially among young perpetrators. They do not understand that they are committing a crime.” As Elena Gajotto adds: “Image-based abuse causes devastating harm to the women who experience it, while the men don’t even understand that they did something bad.”

Several WWP EN members have shared that the most common form of digital violence is men monitoring their partners’ digital activities, e.g. by checking emails, phones and social accounts. This is in line with observations from Daniel Antunovic, from Croatian NGO UZOR, who agrees that the ‘primitive’ forms of digital stalking are the ones he sees most often.

At WWP EN, we consider it key to focus on tech-facilitated abuse to ensure victim safety. Elena Gajotto adds: “Around half of the men share their digital violence, without realizing that this is abuse. If we don’t explicitly focus on this violence in our work with perpetrators, it doesn’t come up.” Therefore, there is a need to increase the capacity of professionals working with perpetrators and professionals working with victims of domestic violence to screen for and intervene in cases of digital violence. As Daniel Antunovic adds: “We haven’t encountered as many cases of digital violence as I expected since COVID-19. However, technology-facilitated abuse is in some ways like sexualized violence. It happens a lot, but it remains hidden.”

There is a growing rate of “smart devices” used in intimate partner violence – Toby Shulruff, Tech Safety Project Manager at NNEDV

NNEDVs Safety Net Project focuses on the intersection of technology, privacy, confidentiality, and innovation, as it relates to safety and abuse by advocating for policies, educating and training advocates and professionals in the justice system, and working with communities, agencies, and technology companies to respond to technology abuse, support survivors in their use of tech, and harness tech to improve services.

While stalkerware is a common concern, there are many other tools available for tech abuse that may appear to be stalkerware, but are not. For example, personal information available online and the everyday features of devices and accounts can be used to find a person’s location or track their activity. The complexity and connections between devices, accounts, and information on the internet can make it difficult for victims and those who work with them to assess what’s happening, and to implement an effective response. It can be terrifying and overwhelming for a survivor to realize an abuser knows multiple details about their everyday lives.

Unfortunately, there is a growing rate of “smart” devices— including home assistants, connected appliances, and security systems connected to WiFi networks and smartphones—used in intimate partner violence.

In a survey conducted by the NNEDV in December 2020 and January 2021, responses revealed an increase in every type of tech abuse during the pandemic. While phones are the technology most often misused, NNEDV’s needs assessment shows this to be the case 87% of the time, “smart” or connected devices were also identified as technologies that are increasingly misused in the context of tech abuse, seen regularly by about a third of support professionals.

As more people adopt the use of IoT devices, this will likely grow. These products are intended to increase convenience and efficiency. The manufacture of IoT devices is a rapidly emerging global market with both larger, well-established players as well as many smaller, newer companies[2]. IoT is made possible by several overlapping trends in technology: miniaturization, increased processing capacity, increased data storage, decreased cost of manufacturing, and connectivity.

Due to a variety of factors – market pressures, the rapid emergence of the technology, and the complexity of the IoT – profound risks to security and privacy are increasingly apparent[3]. Smart home devices in particular are being misused in the context of intimate partner violence to control, threaten, and cause harm to victims. [Researchers at the Gender + IoT project at University College London[4] have been exploring these harms] [and proposing remedies in partnership with support professionals in the field.]

NNEDV’s recent needs assessment documented increases in tech abuse tactics throughout the pandemic. We are concerned that as we emerge from this public health crisis, abusers who have adopted these tactics or have increased their misuse of technology during this time will not have any incentive to discontinue this form of abuse. Recent research[5] suggests support professionals should ask about all kinds of tech abuse, including stalkerware and smart home devices. There is a strong likelihood the spike in tech abuse support professionals have seen will stay with us. It’s imperative we continue to support victims, and work to prevent technology abuse.

How Kaspersky and its partners are collaborating to fight stalkerware

The threat of stalkerware is not just a technical problem: all parts of society need to be involved in resolving the issue. For the past few years, Kaspersky has been at the forefront of the stalkerware debate. We are reaching out to public and private stakeholders to better understand this issue and find common solutions. We are contributing to the development of training materials and practical tools to support non-profit organizations, corporations, institutions and individuals with developing resilience to stalkerware. We are organizing and participating in webinars and roundtables with institutions to share our voices and contribute to discussions that will shape tomorrow’s legislation.

Kaspersky is one of the co-founders and drivers of the Coalition Against Stalkerware (CAS) – an international working group dedicated to tackling stalkerware and combating domestic violence. The Coalition brings together organizations that work with victims and abusers, digital activists and cybersecurity vendors. It is a unique platform that enables all relevant stakeholders to share best practices and join forces to tackle the issue of stalkerware.

Kaspersky is also one of the partners of the DeStalk project. Funded by the European Commission, this research project aims to develop a strategy to train and support professionals working in victims support services and perpetrator programmes, officers of institutions and local governments along with other relevant groups. The consortium plans to upgrade and test existing tools for practitioners and is developing a regional pilot awareness campaign in Italy.

In 2021, we teamed up with INTERPOL and two respected non-profit organizations from the US and Australia to provide law enforcement officials with two online training sessions. These courses were attended by over 210 participants from around the world.

At the end of 2021, Kaspersky also participated in an event, “Combating violence against women in a digital age – utilising the Istanbul Convention”, organized by the Council of Europe. This event was an opportunity to discuss the recommendations of the Group of Experts on combating violence against women and domestic violence (GREVIO).

TinyCheck: a tool to support victims of domestic violence

Kaspersky’s work with the TinyCheck tool is an initiative worth highlighting. It is a free, open-source tool developed and supported by Kaspersky. Initially created to help NPOs protect victims of domestic violence and their privacy, TinyCheck facilitates the detection of stalkerware on victims’ devices and on any OS in a simple, quick and non-invasive way without making the perpetrator aware. While security solutions can also check for and alert about stalkerware, they need to be installed on the device, so there is a risk of the perpetrator also being alerted. Developments like the TinyCheck tool aim to ensure that survivors can use their devices without concerns about being surveilled.

With TinyCheck, no application needs to be installed on the device to perform the check, and the results of the check are not displayed on or transmitted to the potentially infected device. In addition, TinyCheck allows victims to check any device regardless of whether it uses iOS, Android or another OS. These features address the two major issues in the fight to protect users against stalkerware. The tool has been developed to run on a Raspberry Pi, using a regular Wi-Fi connection. TinyCheck quickly analyzes a mobile device’s outgoing traffic and identifies Indicators of Compromise (IOCs), such as interactions with known malicious sources like stalkerware-related servers. Currently, the tool uses IOCs collected not only by Kaspersky researchers but also by repositories maintained by independent security researchers (special thanks to Etienne Maynier, also known as Tek, from Echap and Cian Heasley). We hope that the community will continue this work by keeping IOCs up-to-date.

Having said that, the limitations of TinyCheck need to be understood. The tool should be used with the following warning in mind: IOCs do not provide complete real-time detection of all stalkerware apps like an IT Security solution does. Therefore, a result detecting no stalkerware does not exclude the possibility that stalkerware has been installed but not detected by TinyCheck.

In 2021, more NPOs in the field of domestic violence tested TinyCheck and provided feedback to help improve the service. Police forces and judicial bodies in several countries have also taken an interest in the tool to better support victims.

2021 has seen positive developments on the regulatory and institutional fronts

Across the world, 2021 has seen some positive developments in the fight against stalkerware from a regulatory and institutional point of view. In May 2021, the Diet, Japan’s parliament, enacted a bill to amend their stalker regulation law. Under the revised law, in addition to other stipulations, obtaining location information of people’s smartphones through apps without their authorization is now illegal.

In August 2021, the Federal Trade Commission in the United States barred one app maker from offering stalkerware. It was the first ban of its kind.

On August 17, 2021, the German Bundestag passed the “Act to Amend the Criminal Code – More Effective Combating of Stalking and Better Coverage of Cyberstalking” (translated from German). The new law entered into force on October 1, 2021, and now includes cyberstalking in their catalog of offenses. The change is because of continued technological progress and the associated increase in cyberstalking, particularly via stalking apps or stalkerware. In addition, an important part of the new law is that it classifies a case as serious if the offender “in the course of an offense, uses a computer program whose purpose is the digital spying on other persons.”

The Council of Europe has been very active on this topic in 2021. In its first recommendation on the “digital dimension” of violence against women, the Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO) defines and outlines the problems of both gender-based violence against women committed online and technology-enabled attacks against women, such as legally obtainable tracking devices that enable perpetrators to stalk their victims. This was shortly followed in December 2021 by a legislative initiative report on gender-based cyberviolence that was adopted by the European Parliament. The report calls for (i) a common definition of gender-based cyberviolence and (ii) capacity building for stakeholders. It highlights stalkerware among the key methods of cyberviolence and “dismisses the notion that stalkerware applications can be considered parental control applications”. Following the general recommendations of the Council of Europe, this report, although non-binding, is another positive official document highlighting the stalkerware issue and pushing European states to adapt their legislations and actions to counter the issue. Finally, on March 8th, 2022, the European Commission published a proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on combating violence against women and domestic violence. The document covers cyber violence and dedicates two articles to cyber stalking (Art 8) and cyber harassment (Art 9) that it proposes to criminalize.

Think you are a victim of stalkerware? Here are a few tips

Whether or not you are a victim of stalkerware, here are a few tips if you want to better protect yourself:

- Protect your phone with a strong password that you never share with your partner, friends or colleagues

- Change passwords for all of your accounts periodically and don’t share them with anyone

- Only download apps from official sources, such as Google Play or the Apple App Store

- Install a reliable IT security solution like Kaspersky Internet Security for Android on devices and scan them regularly. However, in the case of potentially already installed stalkerware, this should only be done after the risk to the victim has been assessed, as the abuser may notice the use of a cybersecurity solution.

Victims of stalkerware may be victims of a larger cycle of abuse, including physical. In some cases, the perpetrator is notified if their victim performs a device scan or removes a stalkerware app. If this happens, it can lead to an escalation of the situation and further aggression. This is why it is important to proceed with caution if you think you are being targeted by stalkerware.

- Reach out to a local support organization: to find one close to you, check the Coalition Against Stalkerware website.

- Keep an eye out for the following warning signs: these can include a fast-draining battery due to unknown or suspicious apps using up its charge and newly-installed applications with suspicious access to use and track your location, send or receive text messages and other personal activities. Also check if your “unknown sources” setting is enabled, it may be a sign that unwanted software has been installed from a third party source. It is important to note that the above signs are only symptoms of possible stalkerware installation, not a definitive indication.

- Do not try to erase the stalkerware, change any settings or tamper with your phone: this may alert your potential perpetrator and lead to an escalation of the situation. You also risk erasing important data or evidence that could be used in a prosecution.

[1] https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/consumer-markets/library/covid-19-consumer-behavior-survey.html; https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/how%20covid%2019%20is%20changing%20consumer%20behavior%20now%20and%20forever/how-covid-19-is-changing-consumer-behaviornow-and-forever.pdf;

[2] Internet Society. (2015). The Internet of Things: An overview. https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ISOC-IoT-Overview-20151221-en.pdf or https://www.internetsociety.org/iot/

[3] Internet Society. (2015). The Internet of Things: An overview. https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ISOC-IoT-Overview-20151221-en.pdf or https://www.internetsociety.org/iot/

[4] Tanczer, L., Neira, I. L., Parkin, S., Patel, T., & Danezis, G. (2018). The rise of the Internet of Things and implications for technology-facilitated abuse. University College London.

[5] Freed, D., Palmer, J., Minchala, D., Levy, K., Ristenpart, T., & Dell, N. (2017). Digital technologies and intimate partner violence: A qualitative analysis with multiple stakeholders. Proceedings of the ACM on human-computer interaction, 1(CSCW), p.1-22.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh