Ahead of the Anti-Ransomware Day, we summarized the tendencies that characterize ransomware landscape in 2022. This year, ransomware is no less active than before: cybercriminals continue to threaten nationwide retailers and enterprises, old variants of malware return while the new ones develop. Watching and assessing these tendencies not only provides us with threat intelligence to fight cybercrime today, but also helps us deduce what trends may see in the months to come and prepare for them better.

In the report, we analyze what happened in late 2021 and 2022 on both the technological and geopolitical levels and what caused the new ransomware trends to emerge. First, we will review the trend of cross-platform ransomware development that is becoming more and more widespread among threat actors. Next, we will concentrate on how the ransomware gangs continue to industrialize and evolve into real businesses by adopting techniques of benign software companies. Last, we will delve into how ransomware gangs put on a political hat and engaged in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

Trend #1: Threat actors are trying to develop cross-platform ransomware to be as adaptive as possible

As a consequence of the Big Game Hunting (BGH) scheme that has become increasingly popular over the years, cybercriminals have been penetrating more and more complex environments where a wide variety of systems are running. In order to cause as much damage as possible and to make recovery very difficult (if not impossible), they try to encrypt as many systems as possible. This means that their ransomware should be able to run on different combinations of architectures and operation systems.

One way to overcome this is to write the ransomware in a “cross-platform programming language” such as Rust or Golang. There are a few other reasons to use a cross-platform language. For example, even though the ransomware might be aimed at one platform at the moment, writing it in a cross platform makes it easier to port it to other platforms. Another reason is that analysis of cross-platform binaries is a bit harder than that of malware written in plain C.

In our crimeware reporting section on the Threat Intelligence Platform we cover some of these ransomware variants that work on different platforms. The following are the most important highlights from these reports.

Conti cross-platform functionality

Conti is a group conducting BGH, targeting a wide variety of organizations across the globe. Just like many other BGH groups, it uses the double extortion technique as well as an affiliate-based structure.

We noticed that only certain affiliates have access to a Linux variant of the Conti ransomware, targeting ESXi systems. It supports a variety of different command-line arguments that can be used by the affiliate to customize the execution. The version for Linux supports the following parameters:

| Parameter | Description |

| –detach | The sample is executed in the background and it is detached from the terminal |

| –log | For debugging purposes, with a filename specified, Conti will write the actions to a log file |

| –path | Conti needs this path to encrypt the system. With the selected path, the ransomware will encrypt the entire folder structure recursively |

| –prockiller | This flag allows the ransomware to kill those processes that have the selected files for encryption |

| –size | Function not implemented |

| –vmlist | Flag used to skip virtual machines during the encryption process |

| –vmkiller | It will terminate all the virtual machines for the ESXi ecosystem |

Conti parameters (Linux ESXi)

BlackCat cross-platform functionality

BlackCat started offering their services in December 2021 on the dark web. Although the malware is written in Rust from scratch, we found some links to the BlackMatter group as the actor used the same custom exfiltration tool that had been observed earlier in BlackMatter activities. Due to Rust cross-compilation capabilities, it did not take long time for us to find BlackCat samples that work on Linux as well.

The Linux sample of BlackCat is very similar to the Windows one. In terms of functionality, it has slightly more, as it is capable of shutting down the machine and deleting ESXi VMs. Naturally, typical Windows functionality (e.g., executing commands through cmd.exe) was removed and replaced with the Linux equivalent so the ransomware still holds the same functionality on the different platforms it operates on.

Deadbolt cross-platform functionality

Deadbolt is an example of ransomware written in a cross-platform language, but currently aimed at only one target – QNAP NAS systems. It is also an interesting combination of Bash, HTML and Golang. Deadbolt itself is written in Golang, the ransom note is an HTML file that replaces the standard index file used by the QNAP NAS, and the Bash script is used to start the decryption process if the provided decryption key is correct. There is another peculiar thing about the ransomware: it doesn’t need any interaction with attackers because a decryption key is provided in a Bitcoin transaction OP_RETURN field. The Bash file is shown below.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 |

#!/bin/sh echo "Content-Type: text/html" echo "" get_value () { echo "$1" | awk -F "${2}=" '{ print $2 }' | awk -F '&' '{ print $1 }' } not_running() { echo '{"status":"not_running"}'; exit; } PID_FILENAME=/tmp/deadbolt.pid STATUS_FILENAME=/tmp/deadbolt.status FINISH_FILENAME=/tmp/deadbolt.finish TOOL=/mnt/HDA_ROOT/722 CRYPTDIR=/share if [ "$REQUEST_METHOD" = "POST" ]; then DATA=`dd count=$CONTENT_LENGTH bs=1 2> /dev/null`'&' ACTION=$(get_value "$DATA" "action") if [ "$ACTION" = "decrypt" ]; then KEY=$(get_value "$DATA" "key") if [ "${#KEY}" != 32 ]; then echo "invalid key len" exit fi K=/tmp/k-$RANDOM echo -n > $K for i in `seq 0 2 30`; do printf "\x"${KEY:$i:2} >> $K done SUM=$(sha256sum $K | awk '{ print $1 }') rm $K if [ "$SUM" = "915767a56cb58349b1e34c765b82be6b117db7e784c3efb801f327ff00355d15" ]; then echo "correct key" exec >&- exec 2>&- ${TOOL} -d "$KEY" "$CRYPTDIR" elif [ "$SUM" = "93f21756aeeb5a9547cc62dea8d58581b0da4f23286f14d10559e6f89b078052" ]; then echo "correct master key" exec >&- exec 2>&- ${TOOL} -d "$KEY" "$CRYPTDIR" else echo "wrong key." fi elif [ "$ACTION" = "status" ]; then if [ -f "$FINISH_FILENAME" ]; then echo '{"status":"finished"}' exit fi if [ -f "$PID_FILENAME" ]; then PID=$(cat "$PID_FILENAME") if [ "$PID" = "" ]; then not_running fi if [ ! -d "/proc/$PID" ]; then not_running fi fi if [ -f "$STATUS_FILENAME" ]; then COUNT=$(cat "$STATUS_FILENAME") echo '{"status":"running","count":"'${COUNT}'"}' else not_running fi else echo "invalid action" fi else echo |

Trend #2: The ransomware ecosystem is evolving and becoming even more “industrialized”

Just like legitimate software companies, cybercriminal groups are continually developing their tool kit for themselves and their customers – for example, to make the process of data exfiltration quicker and easier. Another trick that threat actors sometimes pull off is rebranding their ransomware, changing bits and pieces in the process. Let’s delve into the new tools and “business” strategies ransomware gangs are employing these days.

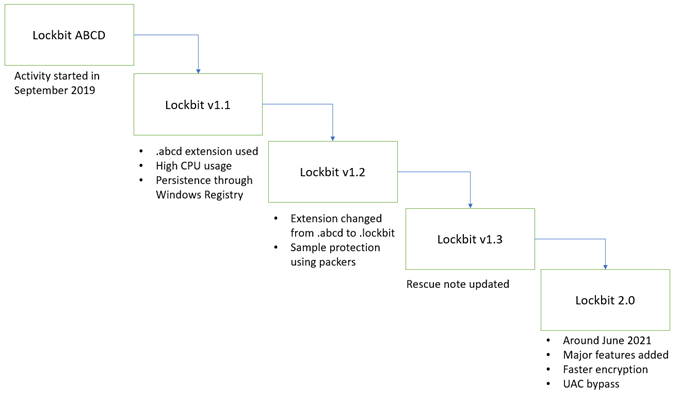

Evolution of Lockbit, one of the most successful RaaS since 2019

Lockbit started in 2019, and then in 2020, its affiliate program was announced. Over time, the group has been developing actively, as can be seen in the figure below:

When the group started with its malicious activities, it did not have any leak portal, was not doing double extortion, and there was no data exfiltration before data encryption.

The infrastructure was also improved over time. Like other ransomware families, Lockbit’s infrastructure suffered several attacks that forced the group to implement some countermeasures to protect its assets. These attacks included hacking of the Lockbit’s administration panels and DDOS-attacks to force the group to shut down its activity.

The latest security addition made by the Lockbit developers is a “waiting page” that redirects users to one of the available mirrors.

StealBIT: custom data exfiltration tool utilized by Lockbit ransomware

Data exfiltration, which is used when groups apply double extortion, is possible in many different ways. Initially cybercriminals used publicly available tools such as Filezilla, and then later replaced them with their own custom tools such as StealBIT. There are a few reasons for this:

- Publicly available tools are not always known for their speed. For ransomware operators speed is important, because the longer it takes to exfiltrate data, the greater the chance that ransomware operators will be caught,

- Flexibility is another reason. Standard tools are not designed with the requirements for ransomware operators in mind. For example, with most tools it is possible to upload the data only to one host. If that host is down, another host must be specified manually. There is always the chance that criminal infrastructure will be taken down or fall into the hands of LEAs. To provide more flexibility and overcome these limitations, StealBIT has a list of hardcoded hosts the data can be exfiltrated to. If the first one is down for some reason, the second host is tried.

- Ransomware operators have requirements that are not met with publicly available tools. One such requirement is to exfiltrate not all the data, but only the interesting data. In StealBIT this is implemented by having a hardcoded list of extensions that should be extracted. Another functionality is that the affiliate ID is sent when data is uploaded.

In the figure below, the data exfiltration is compared (by the authors) to that of other tools:

SoftShade deploys Fendr exfiltration client

Fendr, also known as Exmatter, is a malicious data exfiltration tool used by several ransomware groups such as BlackMatter, Conti and BlackCat. Fendr was not seen in all the BlackMatter and Conti incidents we observed, but we did see them in all BlackCat-related incidents. Therefore, we believe that Fendr was used by a crimeware group that participated in a few affiliate schemes.

Internally, SoftShade developers called it “file_sender” and “sender2”. The malware is written in C# .Net, and was frequently deployed alongside BlackMatter and Conti malware as a packed .Net executable, but most samples deployed alongside Conti and BlackCat ransomware were not packed (except for one Conti incident in November 2021). It is designed to efficiently manage large amounts of selective file collection and upload activity on a victim system and then remove itself from the system. Fendr is built with several open-source libraries, and its design is clearly the result of maturing, professionalised experience in the ransomware space, handling arbitrary large file volumes across various Windows systems and networks.

Also interesting is the deployment and packaging of Fendr and their chosen ransomware. Across each affiliate scheme (except for one Conti incident), the ransomware and Fendr are delivered simultaneously across a network to many systems as “v2.exe” and “v2c.exe”, or as “v2.exe” and “sender2.exe”. This simultaneous push seems to prioritize coordination and efficiency over raising risk of detection. In a Conti-related exception, it appears that a Fendr variant was pushed across the network to many systems as “\\hostname\$temp\sender2.exe”.

Trend #3 Ransomware gangs take sides in geopolitical conflicts

Cybercriminals use news headlines to achieve their malicious goals. We saw this during the initial phase of the global Covid-19 pandemic, when there was a surge of Covid-19-related spam and phishing e-mails. The same happened with the geopolitical conflict in Ukraine in 2022.

There is, however, one big difference. The usage of the pandemic wasn’t personal because it was just another topic from a long list of holidays, events, incidents, etc. In the case of the conflict, threat actors decided to choose sides, and this makes the topic much more personal.

Typically in a geopolitical conflict such as this one, one would associate the source of the cyberattacks with state-sponsored threat actors. This is not always true, as we have noted a new type of engagement in this conflict: cybercrime forums and ransomware groups reacting to the situation and taking action.

There have been consequences: for example, the disclosure of the Conti-related information. We also see this in malware variants that have been recently deployed. Specific variants that are exclusively found in Ukraine or in Russia often choose sides, either against Ukraine or against Russia. Let’s look at the most notable ransomware gang activity around the conflict.

Ransomware gangs taking sides

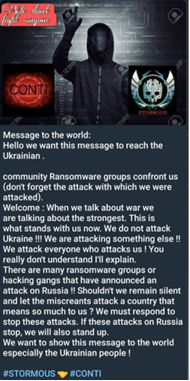

The most significant reaction of all is likely the Conti ransomware group. On February 25, Conti published a message on its news site with a statement that it would retaliate with full capabilities against any “enemy’s” critical infrastructure if Russia became a target of cyberattacks. This is probably a rare example of a cybercriminal group supporting a nation-state publicly. As a result, an allegedly Ukrainian member shared chats and other internal Conti-related information online.

Conti ransomware group posting a warning message on its news site

On the other side there are other communities such as Anonymous, IT Army of Ukraine and Belarusian Cyber Partisans openly supporting Ukraine.

The table below highlights the position of several groups and forums during the beginning of the conflict.

| Open UA support | Open RU support | Neutral |

| RaidForums | Conti | Lockbit |

| Anonymous collective | CoomingProject | |

| IT Army of Ukraine | Stormous | |

| Belarusian Cyber Partisans |

Freeud: brand-new ransomware with wiper capabilities

Kaspersky recently discovered Freeud, a brand-new ransomware variant that supports Ukraine. The Freeud’s ransom note says — not very subtly — that Russian troops should leave Ukraine. The choice of words and how the note is written suggest that it is written by a native Russian speaker. Other language artifacts that we found suggest the authors are non-native English speakers. For example, the word “lending” was found several times in places where the writers should have used “landing”.

The political view of the malware authors is expressed not only through the ransom note but also through the malware features. One of them is wiping functionality. If the malware contains a list of files, instead of encrypting, the malware wipes them from the system.

Another property that stands out is the high quality of the malware, highlighted by the encryption methods applied and the way multithreading is used.

Elections GoRansom (HermeticRansom) covering up destructive activity

GoRansom was found at the end of February in Ukraine at the same time the HermeticWiper attack was carried out. We covered in a post published in March. There are a few things that GoRansom does that are different from other ransomware variants:

- It creates hundreds of copies of itself and runs them.

- The function naming scheme refers to the US presidential elections.

- There is no obfuscation and it has pretty straightforward functionality.

Self-copies made by HermeticRansom

For these reasons we believe it was created to boost the effectiveness of cyberoperations in Ukraine.

Stormous ransomware joins the Ukraine crisis with a PHP malware

It is not very often that we come across malware written in PHP. Most of the time when we analyze PHP code it is either a web shell or some botnet panel code. Stormous is one of the few exceptions. Aside from being a backdoor, it also contains ransomware functionality. The threat actor hunts for web servers supporting PHP technology and weaknesses that are vulnerable to web apps.

An analysis of the malware suggests the threat actor is Arabic speaking from a North African region. Stormous sides with Russia:

The PHP script provides a web interface for remote interaction over HTTP, where several encryption options are offered: “OpenSSL”, “Mcrypt” and “Xor”. It is quite possible that these three were developed into the script because of external considerations at the target, like the version of PHP running on the server (some extensions are deprecated or unavailable from one version to the next).

DoubleZero wiper targets Ukraine

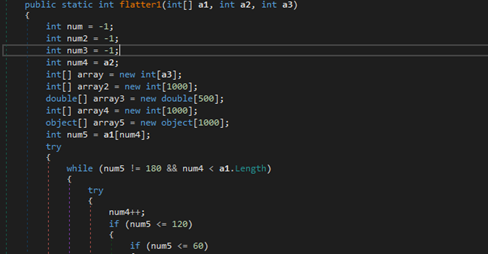

The DoubleZero wiper was initially published by the Ukrainian CERT on the March 22. It is a completely new wiper written in C#; it is not similar to any other known wipers and targets only Ukrainian entities. The binary itself is heavily obfuscated by an unknown C# obfuscator. Classes and method names are randomly generated.

Obfuscation

Control flow is organized using a function-flattening mechanism created to slow down analysis of malicious code.

Obfuscated decompiled code

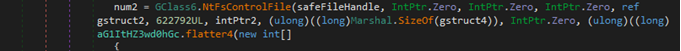

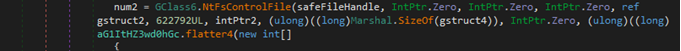

When all the preparations are over, malware starts its wiping operations. First, it checks for user (nonsystem files) by comparing folder names with a hardcoded list and starts wiping them using quite an interesting implementation of NtFsControlFile API.

Hardcoded list of folders

File wiping

The NtFsControlFile routine sends a control code directly to a specified file system or file system filter driver, causing the corresponding driver to perform the specified action. As seen in the screenshot, the control code has the value of 622792 (0x980C8in hex), which corresponds to the FSCTL_SET_ZERO_DATA control code of the FCSTL structure. Data in the file will be overwritten by ZERO values that are pointed by intPtr2 variable. If the function fails, the wiper will execute the standard .Net FileStream.Write function for the same purpose. Then malware wipes the system files found.

Malware then deletes the Windows registry tree subkeys in HKU, HKLM and kills the “lsass” process to reboot the infected machine.

Conclusion

As the saying goes, forewarned is forearmed, and this also applies to cybersecurity. In recent years, ransomware groups have come a long way from being scattered gangs to businesses with distinctive traits of full-fledged industry. As a result, attacks have become more sophisticated and more targeted, exposing victims to more threats. Monitoring the activity of ransomware groups and their developments provides us with threat intelligence that enables better defences.

We witnessed cross-platform ransomware written in Rust and Golang becoming a weapon of the “new-generation” of ransomware groups. Thanks to the software’s flexibility, the attacks can be conducted on a larger scale with no regard to what operating system the victim is using. This flexibility allows ransomware gangs to quickly adapt their strategy when carrying out attacks, diversify their targets and affect more victims.

Second, we witnessed a significant development in how ransomware groups rebuild their inner processes to facilitate their activity increasingly resembling legitimate software developers. While their efforts in branding (and re-branding) aren’t entirely new, the segmentation of their ‘businesses’ as well creation of new exfiltration tools point towards maturing Ransomware-as-a-Service industry, where the ransomware owner simplifies the job for the operators as much as possible.

Finally, ransomware group’s engagement in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine have set a precedent in the way cybercriminals operate in relation to geopolitics. While it is widely seen that advanced persistent threat (APT) actors are usually the ones to take on the mission of carrying out advanced attacks in the interest of the state, we now see that ransomware actors voluntarily engage in such activities as well, often leading to quite destructive consequences.

These tendencies are already affecting the way we need to defend against ransomware today. Ahead of the Anti-Ransomware Day, Kaspersky encourages organization to follow these best practices that help them safeguard against ransomware:

- Always keep software updated on all the devices you use, to prevent attackers from infiltrating your network by exploiting vulnerabilities.

- Focus your defence strategy on detecting lateral movements and data exfiltration to the internet. Pay special attention to the outgoing traffic to detect cybercriminals’ connections. Set up offline backups that intruders cannot tamper with. Make sure you can quickly access them in an emergency when needed.

- Enable ransomware protection for all endpoints. There is a free Kaspersky Anti-Ransomware Tool for Business that shields computers and servers from ransomware and other types of malware, prevent exploits and is compatible with already installed security solutions.

- Install anti-APT and EDR solutions, enabling capabilities for advanced threat discovery and detection, investigation and timely remediation of incidents. Provide your SOC team with access to the latest threat intelligence and regularly upskill them with professional training. All of the above is available within Kaspersky Expert Security framework.

- Provide your SOC team with access to the latest threat intelligence (TI). The Kaspersky Threat Intelligence Portal is a single point of access for the company’s TI, including crimeware, providing cyberattack data and insights gathered by Kaspersky spanning over 20 years. To help businesses enable effective defences in these turbulent times, Kaspersky announced access to independent, continuously updated and globally-sourced information on ongoing cyberattacks and threats, at no charge. Request your access to this offer here: crimewareintel[at]kaspersky.com.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh