2022-9-9 00:7:59 Author: www.thezdi.com(查看原文) 阅读量:21 收藏

In my first blog post covering bugs in Ivanti Avalanche, I covered how I reversed the Avalanche custom InfoRail protocol, which allowed me to communicate with multiple services deployed within this product. This allowed me to find multiple vulnerabilities in the popular mobile device management (MDM) tool. If you aren’t familiar with it, Ivanti Avalanche allows enterprises to manage mobile device and supply chain mobility solutions. That’s why the bugs discussed here could be used by threat actors to disrupt centrally managed Android, iOS and Windows devices. To refresh your memory, the following vulnerabilities were presented in the previous post:

· Five XStream insecure deserialization issues, where deserialization was performed on the level of message handling.

· A race condition leading to authentication bypass, wherein I abused a weakness in the protocol and the communication between services.

This post is a continuation of that research. By understanding the expanded attack surface exposed by the InfoRail protocol, I was able to discover an additional 20 critical and high severity vulnerabilities. This blog post takes a detailed look at three of my favorite vulnerabilities, two of which have a rating of CVSS 9.8:

· CVE-2022-36971 – Insecure deserialization.

· CVE-2021-42133 – Arbitrary file write/read through the SMB server.

· CVE-2022-36981 – Path traversal, delivered with a fun authentication bypass.

Each of these three vulnerabilities leads to remote code execution as SYSTEM.

CVE-2022-36971: A Tricky Insecure Deserialization

I discovered the first vulnerability when I came across an interesting class named JwtTokenUtility, which defines a non-default constructor that could be a potential target:

At [1], the function base64-decodes one of the arguments.

At [2], it checks if the publicOnly argument is true.

If not, it deserializes the base64 decoded argument at [3].

This looks like a possible insecure deserialization sink. In addition, it is invoked from many locations within the codebase. The following screenshot illustrates several instances where it is invoked with the first argument set to false:

Figure 1 - Example invocations of JwtTokenUtility non-default constructor

It turned out that most of these potential vectors require control over the SQL database. The serialized object is retrieved from the database, and I found no direct way to modify this value. Luckily, there are two services with a more direct attack vector: the Printer Device Server and the Smart Device Server. The exploitation of both services is almost identical. We will focus on the Printer Device Server (PDS).

Let’s have a look at the PDS AmcConfigDirector.createAccessTokenGenerator method:

At [1], it uses acctApi.getGlobal to retrieve an object that implements IGlobal.

At [2], it retrieves the pkk string by calling global.getAccessKeyPair.

At [3], it decrypts the pkk string by calling PasswordUtils.decryptPassword. We are not going to analyze this decryption routine. This decryption function implements a fixed algorithm with a hardcoded key, thus the attacker can easily perform the encryption or decryption on their own.

At [4], it invokes the vulnerable JwtTokenUtility constructor, passing the pkk string as an argument.

At this point, we are aware that there is potential for abusing the non-default JwtTokenUtility constructor. However, we are missing two things:

-- How can we control the pkk string?

-- How can we reach createAccessTokenGenerator?

Let’s start with the control of the pkk string.

Controlling the value of pkk

To begin, we know that:

-- The code retrieves an object to assign to the global variable. This object implements IGlobal.

-- It calls the global.getAccessKeyPair getter to retrieve pkk.

There is a Global class that appears to control the PDS service global settings. It implements the IGlobal interface and both the getter and the setter for the accessKeyPair member, so this is probably the class we’re looking for.

Next, we must look for corresponding setAccessKeyPair setter calls. Such a call can be found in the AmcConfigDirector.processServerProfile method.

At [1], processServerProfile accepts the config argument, which is of type PrinterAgentConfig.

At [2], it retrieves a list of PropertyPayload objects by calling config.getPayload.

At [3], the code iterates over the list of PropertyPayload objects.

At [4], there is a switch statement based on the property.name field.

At [5], the code checks to see if property.name is equal to the string "webfs.ac.ppk".

If so, it calls setAccessKeyPair at [6].

So, the AmcConfigDirector.processServerProfile method can be used to control the pkk value. Finally, we note that this method can be invoked remotely through a ServerConfigHandler InfoRail message:

At [1], we see that this message type can be accessed through the subcategory 1000000 (see first blog post - Message Processing and Subcategories section).

At [2], the main processMessage method is defined. It will be called during message handling.

At [3], the code retrieves the message payload.

At [4], it calls the second processMessage method.

At [5], it deserializes the payload and casts it to the PrinterAgentConfig type.

At [6], it calls processServerProfile and provides the deserialized config object as an argument.

Success! We can now deliver our own configuration through the ServerConfigHandler method of the PDS server. This method can be invoked through the InfoRail protocol. Next, we need to get familiar with the PrinterAgentConfig class to prepare the appropriate serialized object.

It has a member called payload, which is of type List<PropertyPayload>.

PropertyPayload has two members that are interesting for us: name and value. Recall that the processServerProfile method does the following:

-- Iterates through the list of PropertyPayload objects with a for loop.

-- Executes switch statement based on PropertyPayload.name.

-- Sets values based on PropertyPayload.value.

With this in mind, we can understand how to deliver a serialized object and control the pkk variable. We have to prepare an appropriate gadget (we can use the Ysoserial C3P0 or CommonsBeanutils1 gadgets), encrypt it (decryption will be handled by the PasswordUtils.decryptPassword method) and deliver through the InfoRail protocol.

The properties of the InfoRail message should be as follows:

-- Message subcategory: 1000000.

-- InfoRail distribution list address: 255.3.5.15 (PDS server).

Here is an example payload:

The first step of the exploitation is completed. Next, we must find a way to call the createAccessTokenGenerator function.

Triggering the Deserialization

Because the full flow that leads to the invocation of createAccessTokenGenerator is extensive, I will omit some of the more tedious details. We will instead focus on the InfoRail message that allows us to trigger the deserialization via the needFullConfigSync function. Be aware that the PDS server frequently performs synchronization operations, but typically does not perform a synchronization of the full configuration. By calling needFullConfigSync, a full synchronization will be performed, leading to execution of doPostDeploymentCleanup:

At [1], the code invokes our target method, createAccessTokenGenerator.

The following snippet presents the NotificationHandler message, which calls the needFullConfigSync method:

At [1], the message subcategory is defined as 2200.

At [2], the main processMessage method is defined.

At [3], the payload is deserialized and casted to the NotifyUpdate type (variable nu).

At [4], the code iterates through the entries of the NotifyUpdateEntry object that was obtained from nu.getEntries.

At [5], [6], and [7], the code checks to see if entry.ObjectType is equal to 61, 64, or 59.

If one of the conditions is true, the code sets the universalDeployment variable to true value at [8], [9], or [10], so that needFullConfigSync will be called at [11].

The last step is to create an appropriate serialized message object. An example payload is presented below. Here, the objectType field is equal to 61.

The attacker must send this payload through a message with the following properties:

-- Message subcategory: 2200.

-- InfoRail distribution list address: 255.3.5.15 (PDS server).

To summarize, we must send two different InfoRail messages to exploit this deserialization issue. The first message is to invoke ServerConfigHandler, which delivers a serialized pkk string. The second message is to invoke NotificationHandler, to trigger the insecure deserialization of the pkk value. The final result is a nice pre-auth remote code execution as SYSTEM.

CVE-2021-42133: One Vuln to Rule Them All - Arbitrary File Read and Write

Ivanti Avalanche has a File Store functionality, which can be used to upload files of various types. This functionality has been already abused in the past, in CVE-2021-42125, where an administrative user could:

-- Use the web application to change the location of the File Storage and point it to the web root.

-- Upload a file of any extension, such as a JSP webshell, through the web-based functionality.

-- Use the webshell to get code execution.

The File Store configuration operations are performed through the Enterprise Server, and they can be invoked through InfoRail messages. I quickly discovered three interesting properties of the File Store:

- It supports Samba shares. Therefore, it is possible to connect it to any reachable SMB server. The attacker can set the File Store path pointing to his server by specifying a UNC path.

- Whenever the File Store path is changed, Avalanche copies all files from the previous File Store directory to the new one. If a file of the same name already exists in the new location, it will be overwritten.

- The File Store path can also be set to any location in the local file system.

These properties allow an attacker to freely exchange files between their SMB server and the Ivanti Avalanche local file system. In order to modify the File Store configuration, the attacker needs to send a SetFileStoreConfig message:

At [1], the subcategory is defined as 1501.

At [2], the standard Enterprise Server processMessage method is defined. The implementation of message processing is a little bit different in the Enterprise Server, although the underlying idea is the same as in previous examples.

At [3] and [4], the method saves the new configuration values.

The only thing that we must know about the saveConfig method is that it overwrites all the properties with the new ones provided in the serialized payload. Moreover, some of the properties, such as the username and password for the SMB share, are encrypted in the same manner as in the previously described deserialization vulnerability.

To sum up this part, we must send an InfoRail message with the following properties:

--Message subcategory: 1501.

--Message distribution list: 255.3.2.5 (Enterprise Server).

Below is a fragment of an example payload, which sets the File Store path to an attacker-controlled SMB server:

Arbitrary File Read Scenario

The whole Arbitrary File Read scenario can be summarized in the following picture:

Figure 2 - Example scenario for the Arbitrary File Read exploitation

- The attacker points the File Store to a non-existent SMB share. This step is optional, but makes the exploit cleaner by ensuring that files from the current File Store location will not be copied to the location where the attacker wants to retrieve the files.

- The attacker points the File Store to a desired local file system path from which he wants to disclose files.

- The attacker points the File Store to his SMB share.

- Files from the previous File Store path (local file system) are transferred to the attacker’s SMB share.

The following screenshot presents an example exploitation of this scenario:

Figure 3 - Exploitation of the Arbitrary File Read scenario

As shown, the exploit is targeting the main Ivanti Avalanche directory: C:\Program Files\Wavelink\Avalanche.

The following screenshot presents the exploitation results. Files from the Avalanche main directory were gradually copied to the attacker’s server:

Figure 4 - Exploitation of the Arbitrary File Read scenario - results

Arbitrary File Write Scenario

The following screenshot presents the Arbitrary File Write scenario:

Figure 5 - Example scenario for the Arbitrary File Write scenario

- The attacker creates an SMB share that contains the JSP webshell.

- The attacker points the File Store to a non-existent SMB share. This step is optional, but makes the exploit cleaner by ensuring that files from the current File Store location will not be copied to the Avalanche webroot.

- The attacker points the File Store to the SMB share containing the webshell file.

- The attacker points the File Store to the Ivanti Avalanche webroot directory.

- Avalanche copies the webshell to the webroot.

- The attacker executes code through the webshell.

The following screenshot presents an example exploitation attempt. It uploads a file named poc-upload.jsp to C:\Program Files\Wavelink\Avalanche\Web\webapps\ROOT:

Figure 6 - Exploitation of the Arbitrary File Write scenario

Finally, one can use the uploaded webshell to execute arbitrary commands.

Figure 7 - Executing arbitrary code via the webshell

CVE-2022-36981: Path Traversal in File Upload, Plus Authentication Bypass

We made it to the final vulnerability we will discuss today. This time, we will exploit a path traversal vulnerability in the Avalanche Smart Device Server, which listens on port TCP 8888 by default. However, InfoRail will play a role during the authentication bypass that allows us to reach the vulnerable code.

Path Traversal in File Upload

Our analysis begins with examining the uploadFile method.

At [1], the endpoint path is defined. The path contains two arguments: uuid and targetbasename.

At [2], the doUploadFile method is called.

Let’s start with the second part of the doUploadFile method, as I want to save the authentication analysis for later in this section.

At [1], the uploadPath string is obtained by calling getUploadFilePath. This method accepts two controllable input arguments: uuid and baseFileName.

At [2], the method instantiates a File object based on uploadPath.

At [3], the method invokes writeToFile, passing the attacker-controlled input stream together with the File object.

We will now analyze the crucial getUploadFilePath method, as this is the method that composes the destination path.

At [1], it constructs deviceRoot as an object of type File. The parameters passed to the constructor are the hardcoded path obtained from getCachePath() and the attacker-controllable uuid value. As shown above, uuid is not subjected to any validation, so we can perform path traversal here.

At [2], the code verifies that the deviceRoot directory exists. From here we see that uuid is intended to specify a directory. If the directory does not exist, the code creates it at [3].

At [4], it validates the attacker-controlled baseFileName against a regular expression. If the validation fails, baseFileName is reassigned at [5].

At [6], it creates a new filename fn, based on the current datetime, an integer value, and baseFileName.

At [7], it instantiates a new object of type File. The path for this File object is composed from uuid and fn.

After ensuring that the file does not already exist, the file path is returned at [8].

After analyzing this method, we can draw two conclusions:

-- The uuid parameter is not validated to guard against path traversal sequences. An attacker can use this to escape to a different directory.

-- The extension of baseFileName is not validated. An attacker can use this to upload a file with any extension, though the filename will be prepended with a datetime and an integer.

Ultimately, when doUploadFile calls writeToFile, it will create a new file with this name and write the attacker-controlled input stream to the file. This makes it seem that we can exploit this as a path traversal vulnerability and write an arbitrary file to the filesystem. However, there are two major obstacles that will be presented in the next section.

Authentication and Additional UUID Verification

Now that we’ve covered the second part, let’s go back and analyze the first part of the doUploadFile method.

At [1], the code retrieves the mysterious testFlags.

At [2], it validates the length of the uuid, to ensure it is at least 5 characters long.

At [3], it performs an authorization check (perhaps better thought of as an authentication check) by calling isAuthorized. This method accepts uuid, credentials (authorization), and testFlags.

At [4], the code retrieves the deviceId based on the provided uuid.

At [5], the code checks to see if any device was retrieved. If not, it checks for a specific value in testFlags at [6]. If this second check is also not successful, the code raises an exception.

At [7], it calls allowUpload to perform one additional check. However, this final check has nothing to do with validating uuid. It only verifies the amount of available disk space, and this should not pose any difficulties for us.

We can spot two potential roadblocks:

-- There is an authentication check.

-- There is a check on the value of uuid, in that it must map to a known deviceId. However, we can bypass this check if we could get control over testFlags. If testFlags & 0x100 is not equal to 0, the exception will not be thrown, and execution will proceed.

Let’s analyze the most important fragments of the isAuthorized method:

At [1], the method retrieves enrollmentId, found within the token submitted by the requester.

At [2], it tries to retrieve the enrollment object from the database, based on enrollmentId.

At [3], it checks to see if enrollment was retrieved.

Supposing that enrollment was not retrieved successfully, the code checks for a particular value in testFlags at [4]. If not, it will return false at [6]. But if the relevant value is found in testFlags, the authentication routine will return true at [5], even though the requester’s authorization token did not contain a valid enrollmentId.

Note that this method also checks an enrollment password, although that part is not important for our purposes.

Here as well, testFlags can also be used to bypass the relevant check. Hence, if we can control testFlags, neither the authentication nor the uuid validation will cause any further trouble for us.

Here is where InfoRail comes into play. It turns out that the Smart Device Server AgentTaskHandler message can be used to modify testFlags:

At [1], it retrieves flagsToSet from the sds.modflags.set property.

At [2], it obtains the Config Directory API interface.

At [3], it uses flagsToSet to calculate the new flags value.

At [4], it saves the new flag value.

To sum up, an attacker can control testFlags, and use this to bypass both the authentication check and the uuid check.

Exploitation

Exploitation includes two steps.

1) Set testFlags to bypass the authentication and the uuid check.

To modify the testFlags, the attacker must send an InfoRail message with the following parameters:

-- Message subcategory: 2500.

-- Distribution list: 255.3.2.17 (SDS server).

-- Payload:

2) Exploit the path Traversal through a web request

The path traversal can be exploited with an HTTP Request, as in the following example:

The response will return the name of the uploaded webshell:

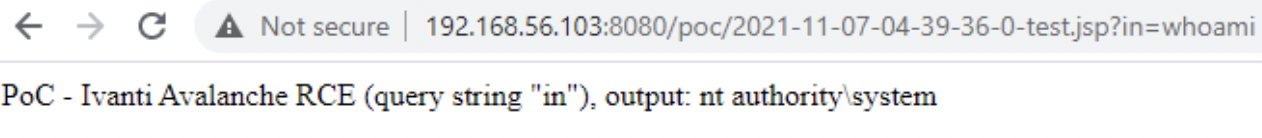

Finally, an attacker can use the uploaded JSP webshell for remote code execution as SYSTEM.

Figure 8 - Remote Code Execution with the uploaded webshell

Conclusion

I really hope that you were able to make it through this blog post, as I was not able to describe those issues with a smaller number of details (believe me, I have tried). As you can see, undiscovered attack surfaces can lead to both cool and dangerous vulnerabilities. It is something that you must look for, especially in products that are responsible for the administration of many other devices.

This blog post is the last in this series of articles on Ivanti Avalanche research. However, I am planning something new, and yes, it concerns Java deserialization. Until then, you can follow me @chudypb and follow the team on Twitter or Instagram for the latest in exploit techniques and security patches.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh