After 4 long months of development, Binary Ninja 3.2 is finally here with a huge list of major changes and an even bigger list of minor ones:

- Enhanced Windows Experience

- Decompiler Improvements

- Objective-C Support

- Segments and Sections Editing UI

- Default to Clang Type Parser

- Named and Computer Licenses for Enterprise

- Many More

While we have some additional Windows improvements coming in future releases, the majority of our short-term Windows roadmap has been completed for this release and should represent a major improvement for all Binary Ninja users working with PE binaries.

Price Change

As a reminder: The price of Commercial license purchases and support renewals will be increasing to $1499 and $749 respectively on November 1, 2022. If you’d like to get a copy (or renew your support) of Binary Ninja Commercial at its current price, act fast! And, if you really like the product, remember that you can purchase multiple years of support at once to lock in the current price.

Major Changes

Enhanced Windows Experience

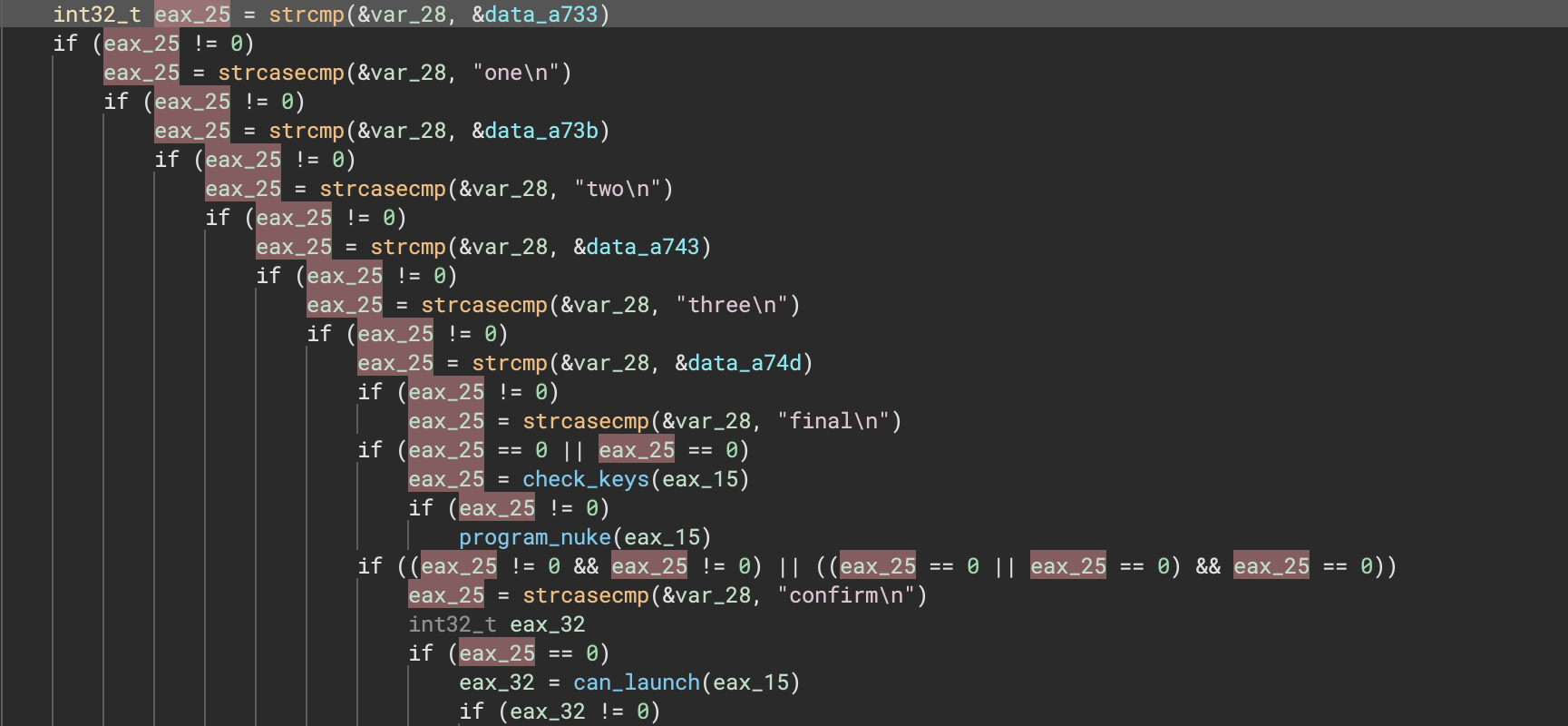

For a long time, we labelled this release as the “Windows” release. While it’s a bit presumptuous to think any single release could contain everything to solve all Windows binary analysis, our goal was to have this release represent a major step forward for PE support. And, of course, not all the features are headliners or Windows-specific, but will still show important improvements. For example, the improved enumeration support below isn’t explicitly for Windows, but PE files definitely benefit, especially with improved type library information.

Improved Enumerations

The most commonly up-voted issue still open is about specifying enumeration values. While that specific issue has unfortunately been moved to the next release, it turns out that changes made on this release render it unnecessary for most situations! With this release, enums are rendered appropriately in most places in IL once the appropriate type has been set. Even better, this is often handled for you automatically with the improved Windows type libraries from 3.1.

Consider the following simple example (to the right) showing how comparisons, math operations, and switch operations using an enum all properly render. Note that this is in addition to existing support for enumerations when typed as a function argument (shown below). That leaves a UI picker to let you choose appropriately matching enums for a given constant as the only remaining feature to be completed.

Next-Generation PDB Support

Binary Ninja’s PDB support has been rewritten from the ground up. Our previous PDB support was written in-house before any public specification releases and, while we’re proud to have had one of the first cross-platform solutions to loading PDB files in a reverse engineering tool (we’ve never required a particular OS to load debug information, all our features are fully cross-platform), our previous solution for loading PDBs was not without downsides. To improve PDB support, we’ve rewritten it entirely to leverage pdb-rs, which we’re happy to be committing improvements to upstream. There’s also more fixes planned once that PR is accepted.

This rewrite resulted in a ton of improvements to Binary Ninja’s PDB support. From leveraging the DebugInfo APIs for automatically applying PDB information when available to much better support for loading types, our ability to ingest PDB information has dramatically improved. It’s also been helpful to have a first-class solution to test the new DebugInfo APIs so that we could work on the workflows and UI associated with loading debug information in a way that will benefit other types of debug information in the future.

But, don’t just take the number of closed issues as proof, here’s a great before/after showing how much better the new PDB support is for one particular binary. Note that significantly more types are being properly extracted:

The experience for loading files with associated PDBs is also vastly improved. Instead of having to manually trigger a PDB load as you did on 3.1 (with the Tools -> Plugins -> PDB -> Load menu option), the default behavior is to simply open a PDB (if one exists) or download one from public PDB servers (if one is available). Additionally, loading a PDB is both faster and results in more accurate analysis. The old default behavior did a full linear sweep and complete analysis before applying any information gleaned from the PDB, which often resulted in redoing a significant amount of analysis. The new behavior is to load and use the PDB before other analysis begins. We also support significantly more search/discovery of PDB files such as following ptr files and environment variables. You can, of course, modify this default behavior using Open With Options or by changing settings in the PDB category.

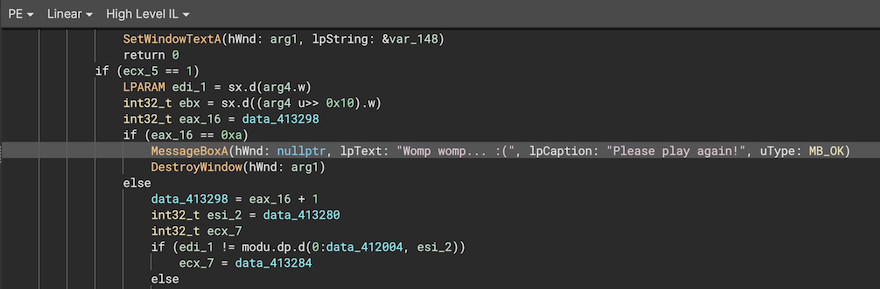

CFG Call Handling

Two important issues for Control Flow Guard (CFG) call handling were fixed that can really improve the reversing experience for PE files. First, the CFG array will now be created and secondly (and more importantly), calls protected by CFG will no longer be opaque in decompilation. Let’s take a look at some disassembly for a call protected by CFG:

call qword [rel MmGetSystemRoutineAddress]

lea r8, [rbp-0x60]

mov qword [rsp+0x20], rsi ; {0x0}

test rax, rax

mov rdx, rdi ; {data_1c002f000, "NdisWan\Parameters"}

mov ecx, r14d ; {0x1}

cmove rax, qword [rel RtlQueryRegistryValues]

xor r9d, r9d ; {0x0}

call qword [rel __guard_dispatch_icall_fptr]

test eax, eax

jne 0x1c00301d7

Not immediately obvious what’s going on, is it? Prior to 3.2, here’s what the decompilation looked like:

RtlInitUnicodeString(&var_7f0, "RtlQueryRegistryValuesEx")

MmGetSystemRoutineAddress(&var_7f0)

if (sub_1c0001330(1, "NdisWan\Parameters", &var_788, 0, 0) == 0)

In 3.2, however, you can much more easily see that the call is to RtlQueryRegisterValuesEx:

int64_t rax_13 = MmGetSystemRoutineAddress(&var_7f0)

int64_t (** r8_5)(int64_t arg1, int32_t arg2, int32_t* arg3, int32_t arg4, int32_t* arg5) = &var_788

if (rax_13 == 0)

rax_13 = RtlQueryRegistryValues

if (rax_13(1, "NdisWan\Parameters", r8_5, 0, 0).d == 0)

In fact, if you want to make it even more obvious, you can switch to MLIL, use User-Informed Dataflow and hard-code the value of rax_13 to a ConstantValue of 0 for all return values of MmGetSystemRoutineAddress. You’ll get something even simpler:

if (RtlQueryRegistryValues(1, "NdisWan\Parameters", &var_788, 0, 0).d == 0)

A few lines of Python can fully automate this for all cross-references, too!

zero = PossibleValueSet.constant(0)

for ref in bv.get_code_refs(bv.get_symbols_by_name('MmGetSystemRoutineAddress')[0].address):

if isinstance(ref.mlil, Localcall):

v = ref.mlil.vars_written[0]

ref.mlil.function.source_function.set_user_var_value(v, ref.address, zero)

MS Demangler Improvements

One of the problems our users have been facing when disassembling Windows targets is symbols not being demangled and having their type information applied properly. To this end, we’ve made a number of improvements in our demangler to better handle some of the edge cases we missed before:

- PE files compiled with

gccorclanghave a slightly different format than MSVC for their mangled function names. These are now handled properly. - Functions with mangled names that specify or hint at a certain calling convention will now properly pass that information along to Binary Ninja. We may not actually use that information if we have a better source of truth (it is, occasionally, a lie), but it is no longer outright ignored.

- As an example of the edge case above, demangled C++ types no longer override types provided from our platform type libraries. Our type libraries are a manually curated set of types with higher confidence, so we always prefer their information over what’s been recovered from the binary via demangling.

- A large number of MSVC mangled names that were not demangled properly before, now are. Reaching feature parity with a closed-source compiler that is always changing is a Sisyphean task, so we still have some edge cases we don’t handle properly. But, we now handle many new conventions correctly. See this issue for an example of some of the mangled names we do (and don’t) handle properly. (And, if you’ve got some others, please let us know!)

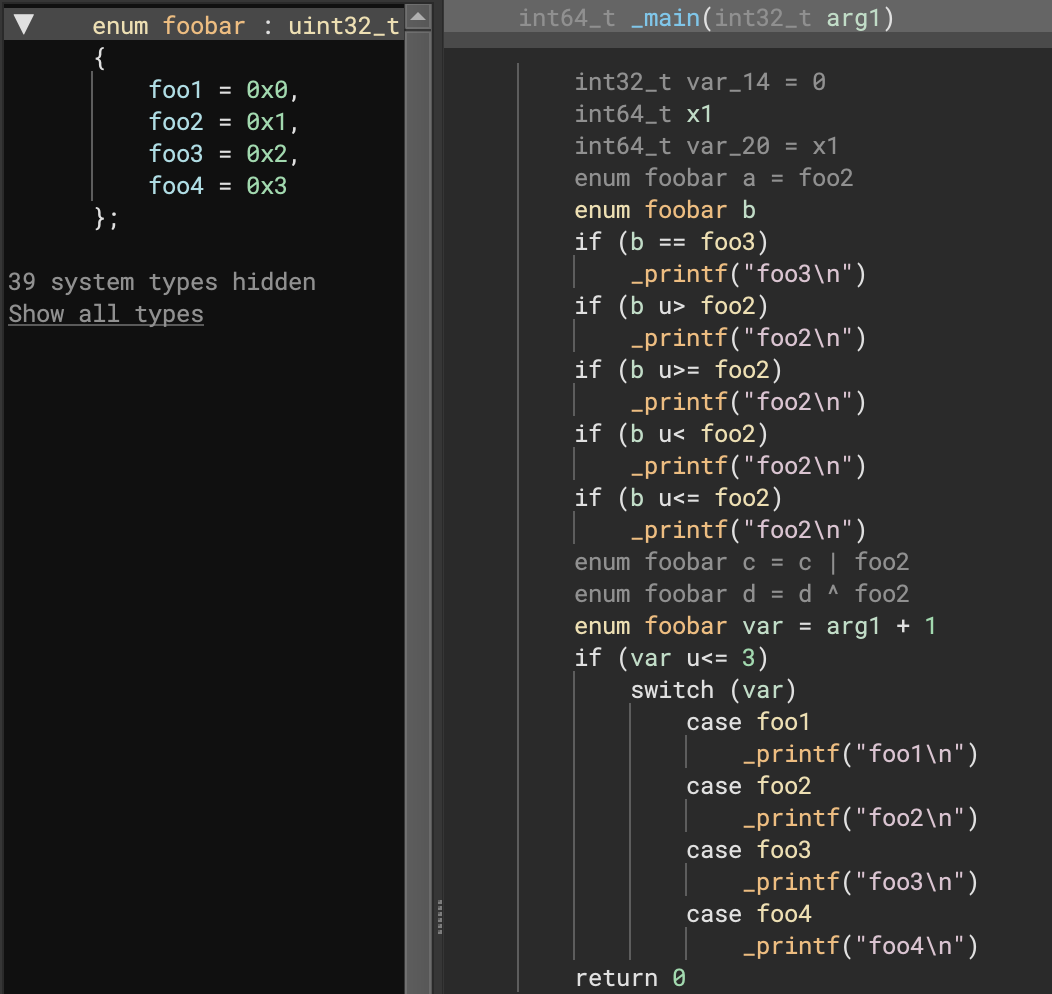

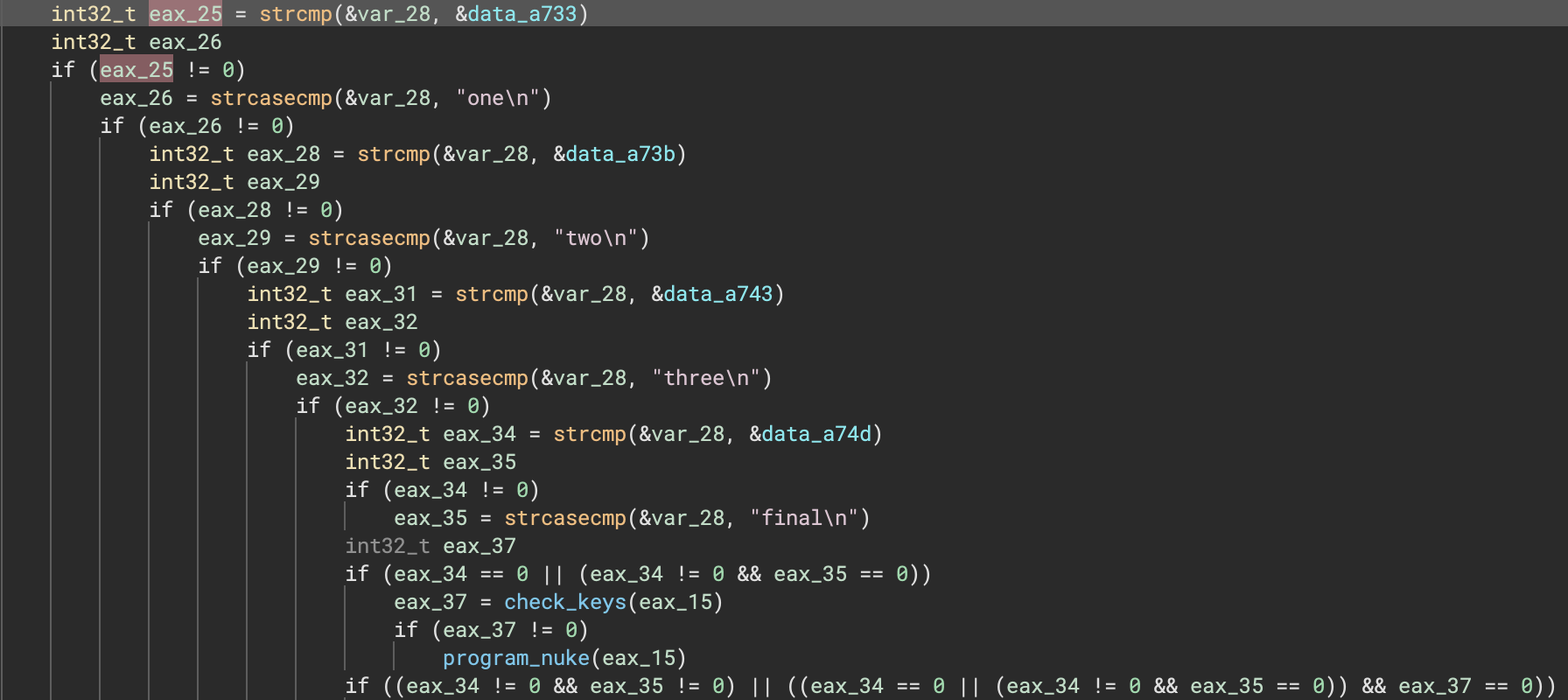

Decompiler Improvements

Want to know a secret? Decompilers are impossible. Ok, clearly they’re not or we wouldn’t be talking so much about ours. Instead let’s say that perfect decompilation is impossible (barring extra debug information or some other outside source of information). So if no decompiler can be perfect, how do you get the best result possible? You automate as much as you can, provide the best APIs for third-parties to automate as much as possible, and you make sure that the quality of the decompilation can be improved either manually or via those APIs when perfect automatic recovery isn’t possible. To that end, we’ve introduced several important features that can dramatically improve the performance of our decompiler both automatically and when manually informing analysis.

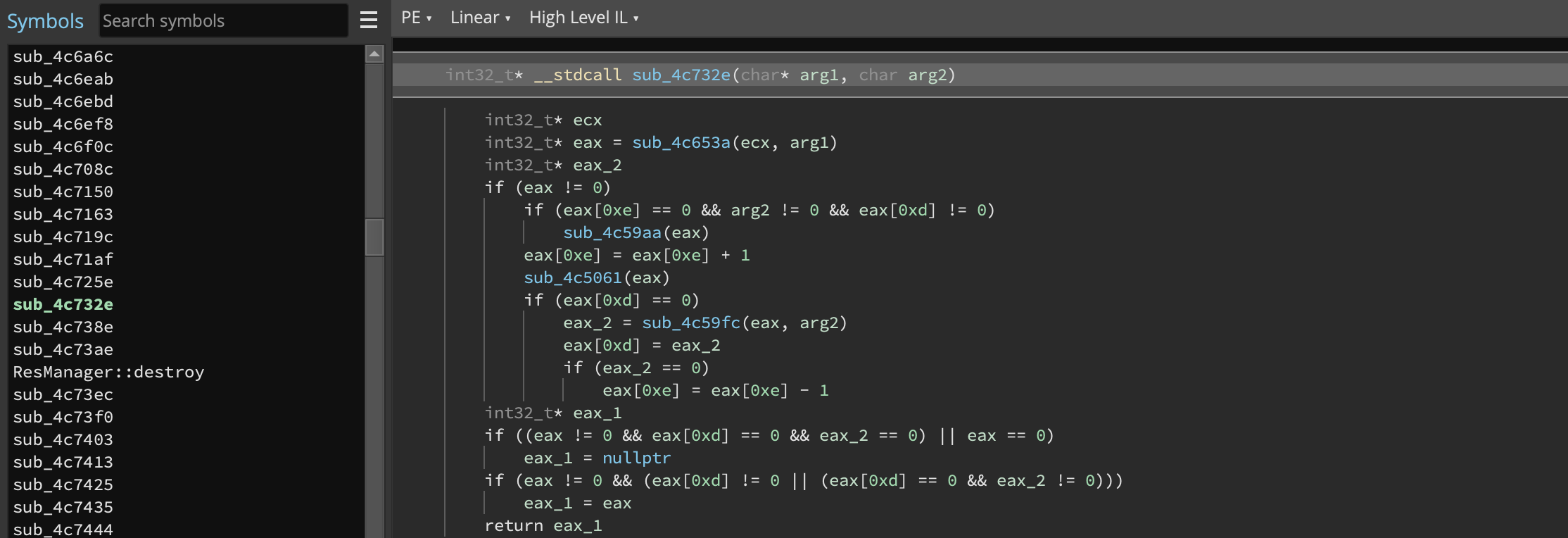

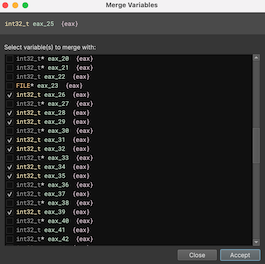

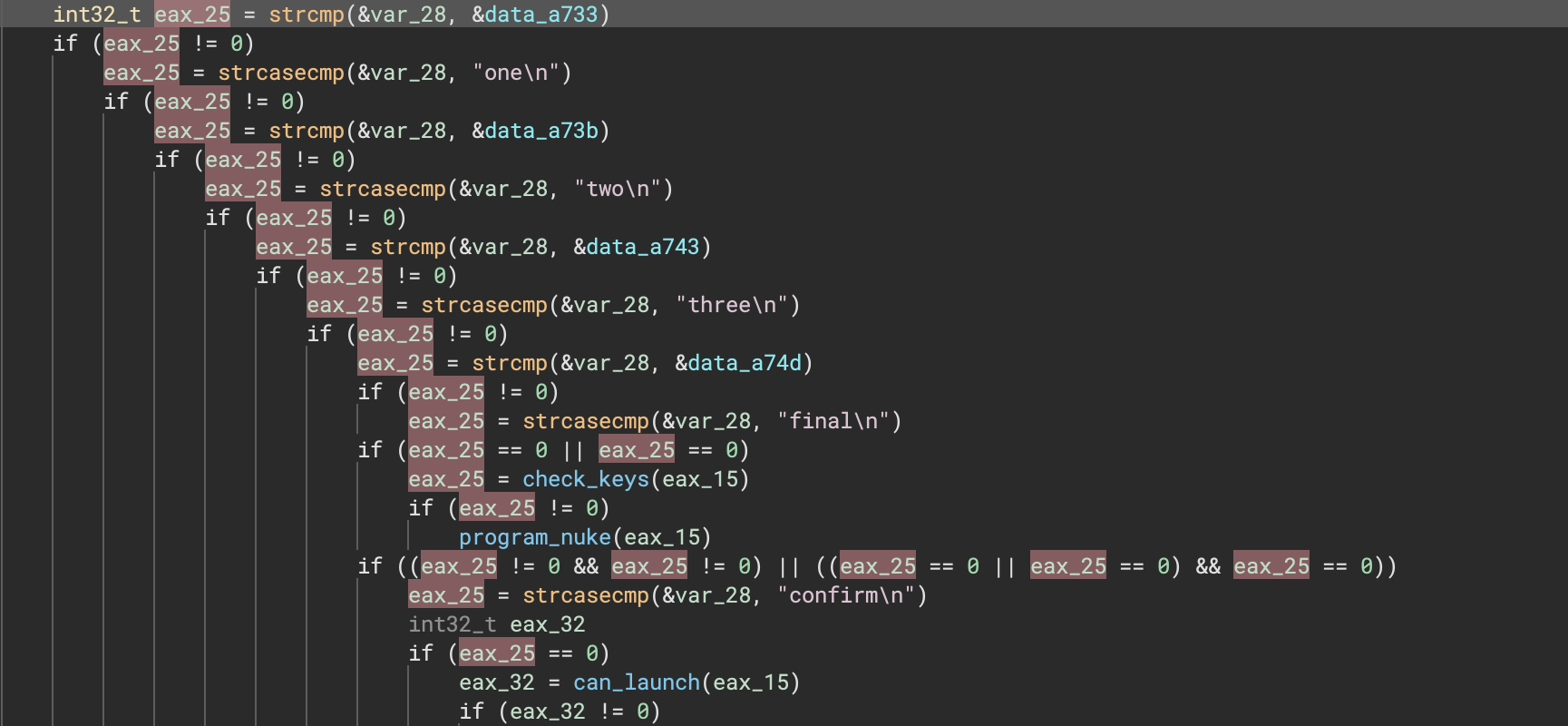

Variable Merging/Splitting

Our second most highly-requested feature before this release was the ability to merge and split variables. There are many reasons you might want to merge or split a variable. Usually, it’s a case of you, the reverse engineer, being more confident about a variable use being the same or different than the decompiler’s analysis. Or, sometimes, it’s just wanting to simplify the representation even if it’s not a sound transformation.

Consider the following before/after when splitting variables:

mov al, [ecx]

mov dl, al

mov al, [ecx+1]

add dl, al

mov al, [ecx+2]

add dl, al

mov al, [ecx+3]

add dl, al

mov al, [ecx+4]

add dl, al

mov al, [ecx+5]

add dl, al

mov al, [ecx+6]

add dl, al

mov eax, edx

retn

This optimized copy by default will render in HLIL as:

int32_t edx

edx.b = *arg1

edx.b = edx.b + arg1[1]

edx.b = edx.b + arg1[2]

edx.b = edx.b + arg1[3]

edx.b = edx.b + arg1[4]

edx.b = edx.b + arg1[5]

edx.b = edx.b + arg1[6]

return edx

If, instead, you right-click on the first edx.b and choose Split Variable at Definition (and repeat the process for each new variable), you can end up with the much more simplified:

int32_t edx_6

edx_6.b = *arg1 + arg1[1] + arg1[2] + arg1[3] + arg1[4] + arg1[5] + arg1[6]

return edx_6

Note that you will receive a warning when selecting this option as it can result in unsound analysis! Don’t worry, though, there’s always a fast “Undo” if it doesn’t do what you expect.

Likewise, sometimes the decompiler thinks two uses of the same variable are distinct when they aren’t and you may want to merge them. In that case, select the variable you’d like to merge into and either use the = hotkey or right-click and select Merge Variables....

Next, select one or more variables to merge with and the decompilation will be updated accordingly. If you change your mind, you can either use the undo hotkey, menu item, or re-use the same right-click menu and de-select a particular variable that was merged from the dialog.

Here’s a nice before and after showing how much cleaner the decompilation can be for one example:

Offset Pointers

Offset pointers, often called shifted pointers or relative pointers, are used to provide extra information about the “origin” of a pointer. They can include offset information about a struct and member, for example. Note that this offset can be negative and is quite useful in a number of situations. The best part is that you can get most of the benefits automatically as Binary Ninja will attempt to identify these references without any interaction. When Binary Ninja is unable to resolve an access through the pointer type directly, it will attempt to resolve the type a second time using the adjusted base (and lifting the access in terms of an access against the origin pointer type instead of the pointer’s direct type).

When arithmetic operations are performed on pointer types, Binary Ninja’s analysis automatically stores this information in the resulting type. (It isn’t shown in the UI unless the resulting type is unknown, though, but it can be used later.) For example, given the following:

struct SomeStruct {

uint64_t a_member;

char some_array[0x100];

};

…and given that we have a pointer of type SomeStruct* our_example_pointer;, an 8-byte load such as [our_example_pointer].q would be translated as an access to a_member and a one-byte access like [our_example_ptr + 0x60].b would be treated as an access into some_array.

But, what would we expect the types of [unknown_type] example1 = our_example_pointer + 0x8 and [unknown type] example2 = our_example_pointer + 0x300 to be? While the simplest answer might be that example1 is just a char*, our more complete answer is that it would be char* __offset(SomeStruct, 0x8). For example2, we can’t determine a useful type to use as the pointed-to type directly, but we can at least leverage both our confidence systems and offset systems to arrive at void* __offset(SomeStruct, 0x300), where we have 0 confidence in the void component of the type.

Now that we’ve seen some examples where analysis would generate offset pointer types, let’s look at where we leverage those types in the analysis to improve our output: How should we pick types for [unknown_type] example3 = [example1 + 1].b or [unknown_type] example4 = [example2 - 0x300].q?

For example3, it’s easy enough to see that we’d give example1[1] a result of char, though we’d have the option of two ways to understand it: example1[1] or (example1 - 0x8)->some_array[1], thanks to the extra information we’ve preserved in the type. For example4, the motivation becomes clearer: Despite ostensibly being a pointer to a void type, we’re able to subtract the displacement of the load from the pointer offset to translate this as uint64_t example4 = (example2 - 0x300)->a_member;.

This tracking of pointer offsets is enabled for all constant value add/subtract operations involving pointers to struct types or pointer types that already have offset information associated with them. In order to improve readability of our output, we don’t render the __offset(origin, offset) components in pointer types unless:

- They are derived directly from user input

- The direct pointed-to type of the result of an arithmetic op is a low confidence void type (e.g., a pointer to a member that Binary Ninja doesn’t know about yet)

This makes it so that a pointer to a struct member that exists will render as it did before, minimizing clutter, even though that information is still tracked in the type and can be accessed through the API.

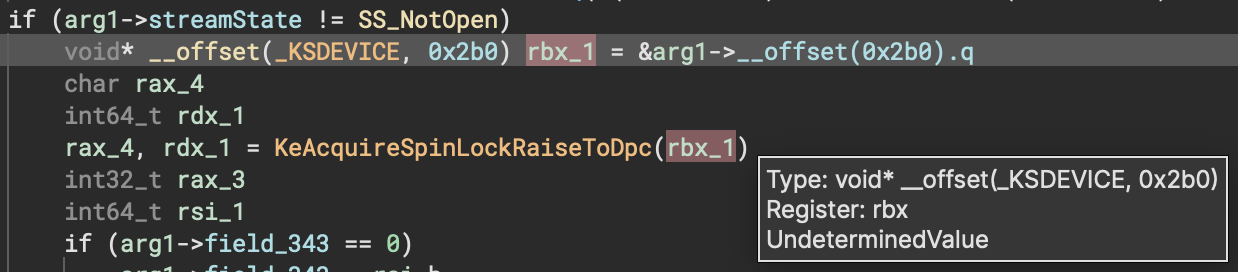

One area where our new offset pointers shine is making it easier to identify and mark up struct members. In the example below, _KSDEVICE is only partially marked up and there’s no member at offset 0x2b0 yet (making this similar to example2 above). This immediately draws attention to how pointers to unknown members are used in the function, making it easy for a user to go back and contribute that information to the struct type in the form of new members or changes to existing members.

Of course, automatic analysis might not find all offset pointers or propagate them as far as you’d like. If you need to specify one manually, you can do so using the syntax shown in the screenshot above.

Split Loads and Stores

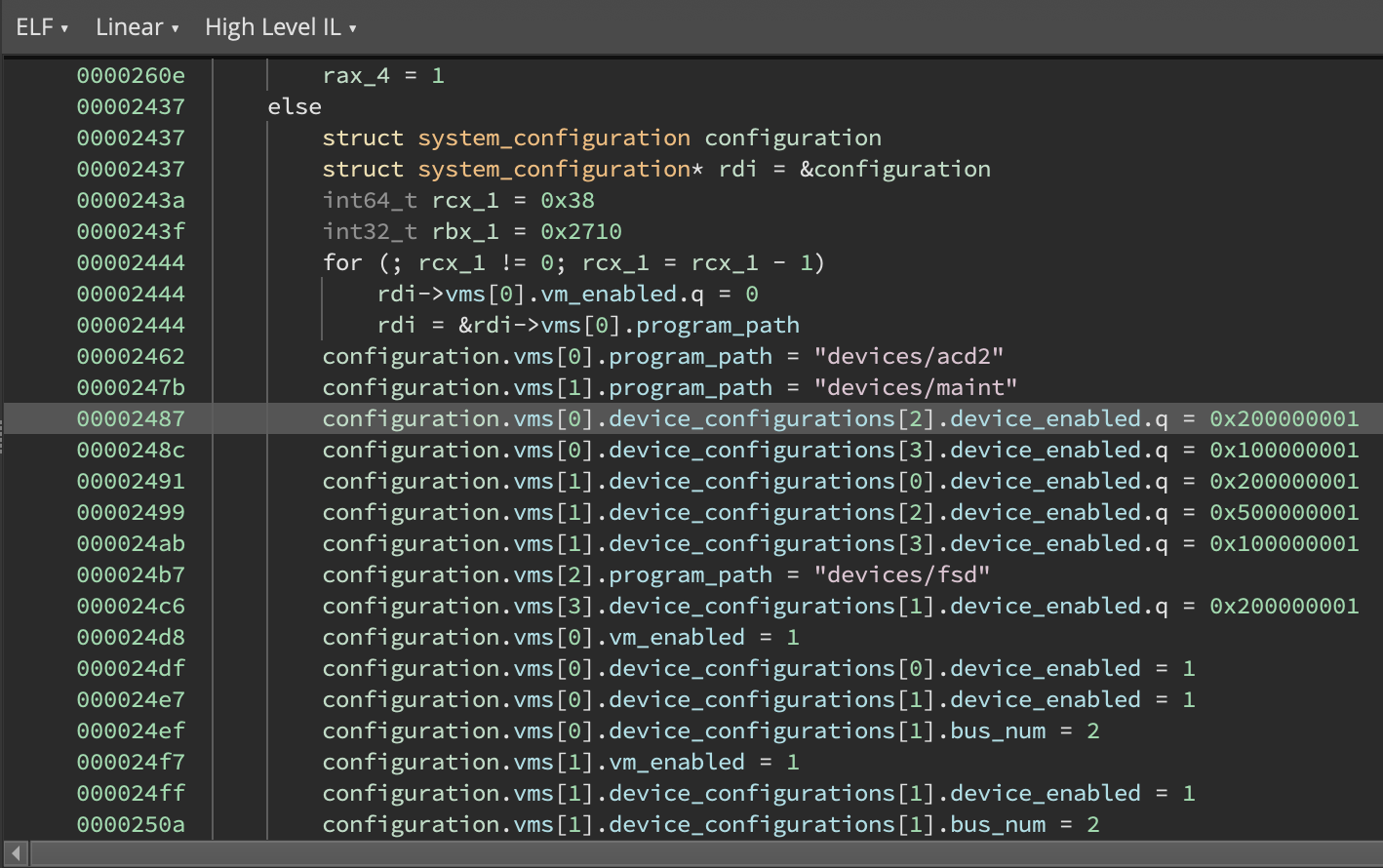

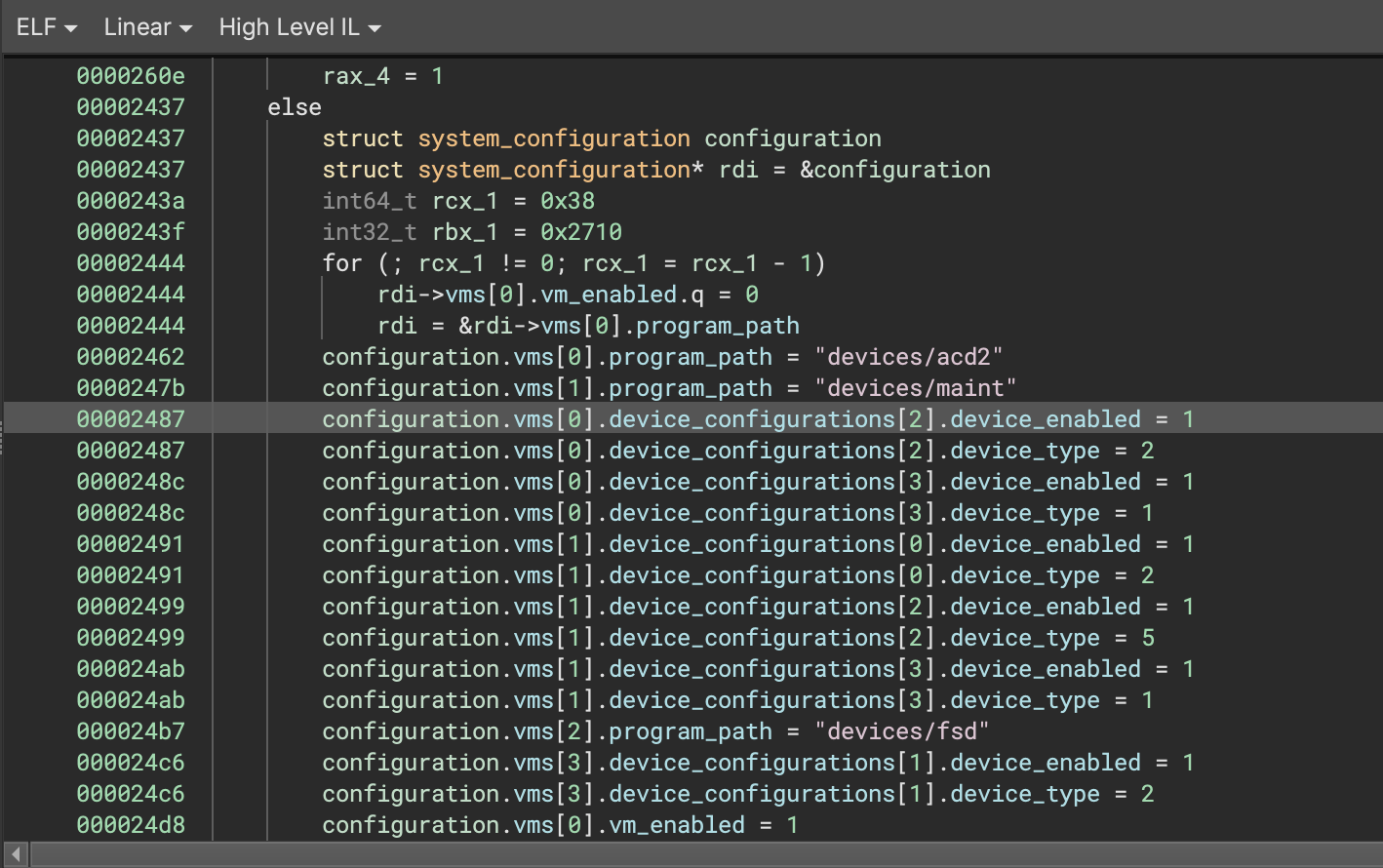

In 3.2, Binary Ninja can now split memory accesses that span multiple struct members into separate operations for each member while respecting the size of each member. We apply this transformation during MLIL generation, and it’s reflected in both MLIL and HLIL output. One of the most common scenarios where this is useful is when a compiler sets multiple adjacent fields to constant values with a single store of an oversized constant as an optimization, seen here:

This feature is motivated by compilers frequently setting multiple fields in a single assembly instruction, such as during copies by value, moves, and initialization of adjacent members with constant values. This previously posed issues for accurate tracking of struct member cross-references as each memory access would only generate one cross reference into a struct.

As MLIL is largely where our analysis becomes type-aware, respecting type information available to us during translation is a natural step forward. This change allows us to ensure that all struct members accessed receive their own MLIL instructions, and additionally allows us to trim out loads/stores to gaps in a struct (e.g. padding/alignment bytes that aren’t actual members).

Load/store splitting can operate in three different modes, controlled by its settings in the MLIL category. The three modes are off, validFieldsOnly, and allOffsets:

offsupresses splitting entirely, meaning that MLIL memory accesses always have a size matching the LLIL operation from which they were derived.validFieldsOnlyemits size-respecting accesses to all struct members, and omits accesses to any gaps in the structure.allOffsetsensures that all bytes touched by an access will have correspond to at least some instruction in the MLIL translation, even if there’s no members for some portion of the access. In other words, an 8 byte store operation in LLIL will always have 8 bytes worth of MLIL accesses, respecting type information for members where available.

We’ve selected validFieldsOnly as the default behavior. While this might seem like a loss of some information due to skipping gaps in a struct, we believe this is well-motivated for a few reasons:

- Due to our architecture leveraging the use of multiple ILs representing different levels of abstraction, information about the size of the access performed by the assembly instruction is preserved within LLIL.

- In the absence of knowledge of the size of any potential members here, our only option would be to guess at the width and even the number of members in the gap we’re trying to fill, with the consequence of contributing cross-references with bogus sizes into the struct type.

- By not contributing cross-references to gaps in a struct from accesses that we’ve split, that leaves appropriately-sized accesses to those regions of the struct elsewhere in the binary free to contribute cross-references that are accurate without us adding clutter.

Here’s an example showing an 8 byte struct having a uint8_t member added into the middle of a 3 byte gap would look like, in both HLIL and MLIL:

We perform load/store splitting where at least one side of the operation involves a struct, accesses at least two members, and where the overall instruction a simple copy (e.g. read/write from struct, variable, constant, etc.).

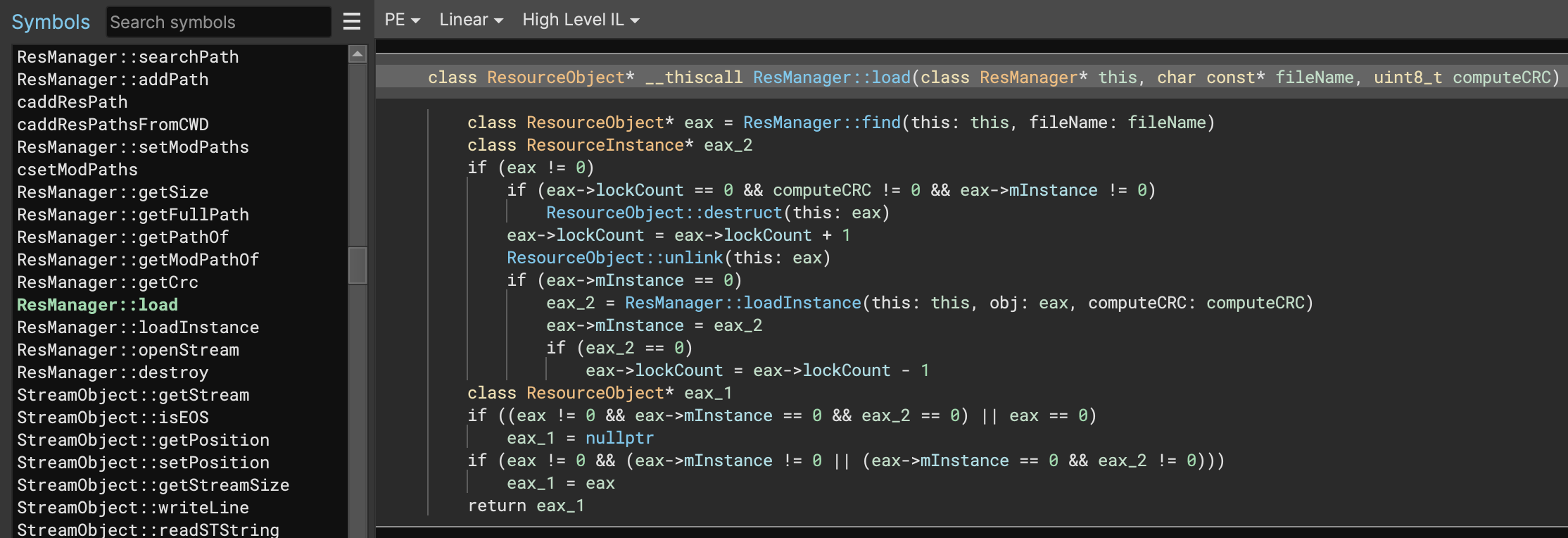

Objective-C Support

While Objective Ninja was originally a plugin built on the Workflow API implemented by Jon after his internship last summer, it’s been integrated and adopted internally and is now maintained as a first class feature. It’s keeping its open source roots (along with many other components that were developed in-house and later released as open source projects) and contributions are welcome.

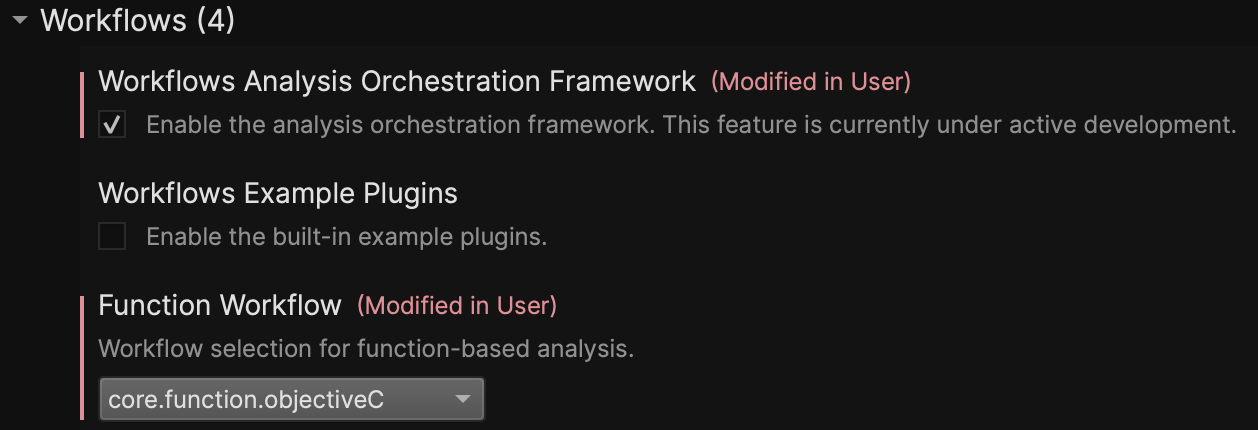

Like other Workflows, the current model for using it requires both changing the Function Workflow setting as well as enabling the Workflow Framework. Future work will remove this step entirely, causing the workflow to be automatically loaded and used when appropriate.

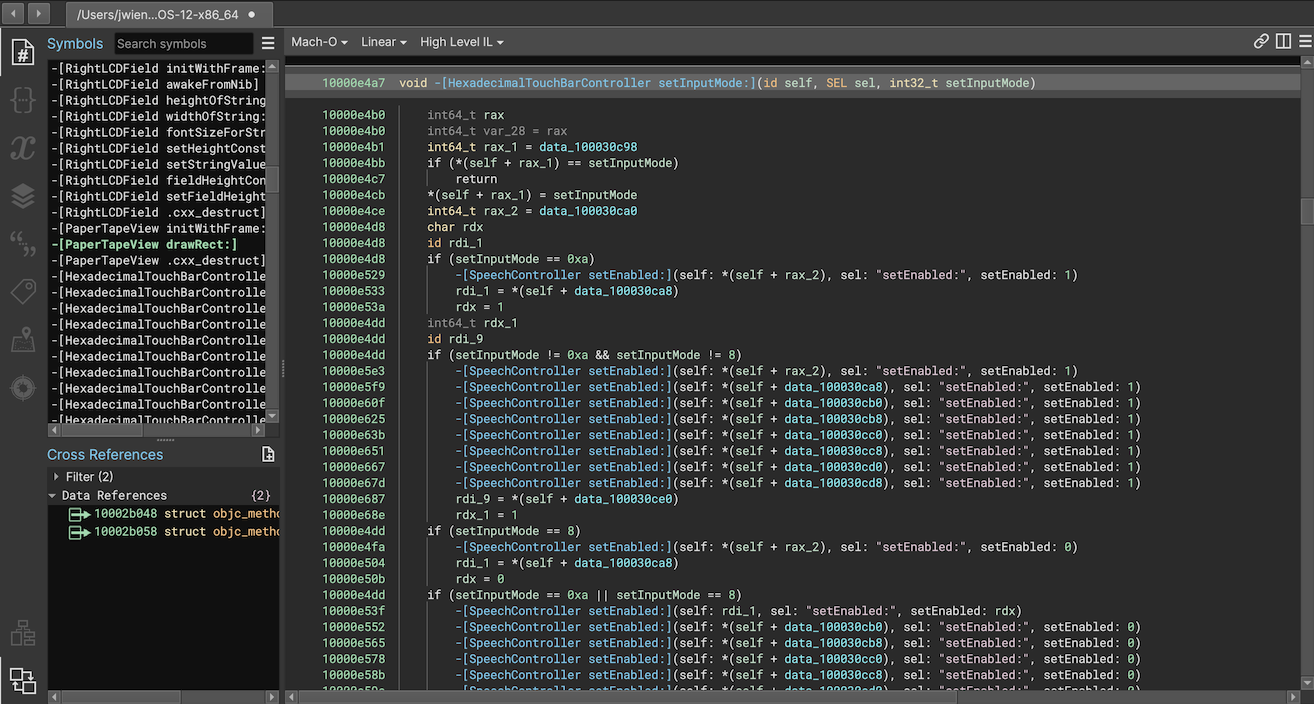

How much of a difference does this make? A huge one! Using the Workflow API the plugin can rewrite the IL producing true virtual method calls instead of simply annotating a call to msgSend. That, plus parsing and loading types and symbols makes the improvement extremely obvious. Here’s a quick before-and-after when using it to analyze /Applications/Calculator.app:

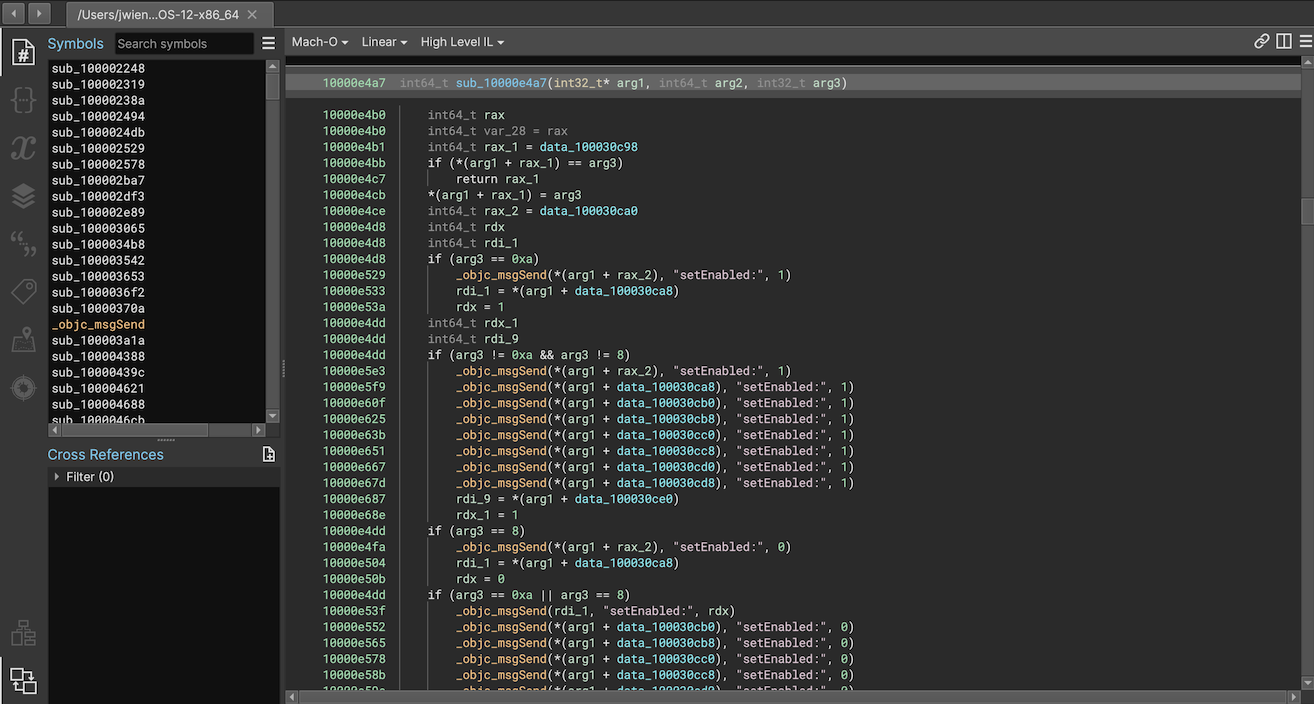

Segments and Sections Editing UI

New to 3.2 is the Memory Map, which allows for editing Segments and Sections. While this was originally slated for the upcoming ‘embedded’ milestone, we slipped an early version into this release. Note that the UI is not final and it will likely receive some additional polish changes in the upcoming release but we figured folks would rather have it sooner than later!

The future release will include a version of this UI during open-with-options to let you define segments and sections when opening a flat file instead of the current loader.segments and loader.sections settings.

Both segments and sections can be created using the right-click menu, and while some segments cannot be edited after a view is loaded, sections can always be edited.

This feature can be especially useful when analyzing files whose section permissions impact Binary Ninja’s data-flow analysis. For example, a section marked “writable” will not make any assumptions about the contents. If the sections contain data it’s useful to let the analysis assume is still the same, you can either mark individual variables as const, or you can simply change the section permissions to make the entire section read-only. Note however, this might result in incorrect decompilation in the case of global variables that are not constant.

Default to Clang Type Parser

The new type parser we added as a beta feature in 3.1, the Clang type parser, is now our new default. As you might’ve guessed from the name, this type parser now leverages clang instead of our custom “Core” type parser. The biggest thing this enables us to do is consume header files directly - even big behemoth headers like windows.h!

This new type parser supports a whole lot of stuff, including:

- Basic types

- Structures

- Unions

- Enumerations

- Functions

- Variables

- Includes

- Macros

- Attributes

__packedstructures- Structure offsets like

__offset(0x8)(see the section on Offset Pointers above) - Calling conventions with

__convention(("name")) @ eax-style register locations- Syscalls like

__syscall(0) __noreturn

- Escaped identifiers (with backticks)

- This means types that include

<,>,:, and other commonly reserved glyphs will now also work

- This means types that include

- …and probably some others we’re forgetting to mention

Named and Computer Licenses for Enterprise

When we launched our Enterprise edition 11 months ago, we did so with floating licenses managed completely by the Enterprise server. This configuration enables large, Enterprise organizations to have a pool of licenses they can have available for incidental use. Unfortunately, floating licenses can sometimes be a hassle for users that are consistently using Binary Ninja Enterprise day in and day out - even with the option to check out a floating license for a long period of time.

To address this, we now have named and computer licenses available for purchase with Enterprise. Clients using these licenses are not tied to any specific Enterprise server (great for environments with multiple servers) and will not use up a floating license when connected. New purchases of Enterprise can opt for named or computer licenses in lieu of floating, and existing Enterprise customers can contact us to have existing floating licenses swapped out for named or computer licenses when renewing support.

Other Updates

Special thanks to kr1tzy, d0now, Lukas-Dresel, ehntoo, holmesmr, yrp604, nshp, and ek0 for your contributions to our open source components!

Documentation

While it’s not in the “major changes” section, for many people the many improvements made to the user and API documentation might indeed be major! First, the Getting Started Guide is no-longer a catch-all for all documentation but as its name implies, it’s actually a brief guide just to get you started. Much of the content that used to live there is now in the User Manual which also contains a number of other sections.

Not only that but we’ve updated the layout to use mkdocs for material as you can see above. This lets you more quickly navigate between both sections and topics.

And it’s not just the user documentation being improved – we’ve also completely refreshed the C++ documentation. The C++ improvements aren’t just skin deep either! Kat has been hard at work cleaning up and adding documentation so the C++ APIs are no longer just the leftovers amongst all our documentation but are significantly more complete. This means the C++ docs are no longer a bare-bones resource, but a much more complete and useful reference. This is especially helpful if you’ve struggled to work with the PySide/binaryninjaui APIs that cannot be documented using our existing Sphinx documentation system.

UI Updates

- Feature: Add “Restart and Reopen Files” command

- Feature: “Run Script” Action and menu item

- Feature: Add a recent file right-click menu for ‘Open with Options’

- Feature: Lots of new “magic” console variables

- Feature: Add “Zoom to Fit” and “Zoom to Cursor” hotkeys

- Feature: Add various filtering options to StringsView

- Feature: Add ‘Copy’ options in the ‘Strings’ and ‘Symbols’ views

- Feature: Restore window layout and location when reopening files

- Feature: Show list of imported libraries in TriageView and if they have TypeLibrary information or not

- Feature: Hotkeys for toggling integer size “D” and and sign “-“ in TypesView

- Feature: Kill to end of line hotkey in python console

- Feature: Undo/Redo now show action summaries for what will be done or undone

- Feature: New Light Theme (Summer)

- Improvement: Configurable HLIL tab width

- Improvement: Move exact match to top of symbol list if found

- Improvement: Hotkeys now searchable in the keybindings menu

- Improvement: Wayland support (partial)

- Improvement: Consistency of hotkeys in StackView (1, 2, 3)

- Improvement: Menu organization (1, 2)

- Improvement: Allow programmatically closing a global area widget

- Improvement: “firstnavigate”, prefer triage, and other potentially conflicting default options normalized and documented

- Fix: Text rendering glitch in hex view on Windows

- Fix: Default font on Windows along with other font related improvements

- Fix: Create structure ‘S’ hotkey wasn’t appearing to work during analysis

- Fix: Right-click losing selection

- Fix: BN hangs when it fails to open a URL

- Fix: SettingsView filtering bug when pasting search text

- Fix: ‘Display As’ for array index annotations

- Fix: Various theme handling fixes (1, 2)

- Fix: x86 assembler on Windows

- Fix: Missing linear view updates when creating analysis objects via API

Binary View Improvements

- Improvement: PE more in-depth parsing of the

LoadConfigstructure - Improvement: PE create a symbol for the

__security_cookie - Improvement: PE make DataVariables for XFG hashes

- Improvement: PE identify

_guard_check_icalland_guard_check_icall_checkand their pointers - Improvement: PE Demangle GNU3 (clang) Mangled Names

- Improvement: ELF Thumb2 entry point detection

- Improvement: Mach-O Create DataVariables for ‘dylib’ and ‘dylib_command’

- Improvement: Mach-O Fix DYLIB and DYLD commands

- Improvement: Mach-O Warn when encountering an unsupported

INDIRECT_SYMBOL_LOCALsymbol - Fix: COFF loader does not respect address size when creating external symbols

- Fix: COFF loader now recognizes (and stops loading) CIL and import library COFF files

- Fix: PE Bug with parsing exception handlers

- Fix: ELF hang when displaying DataVariables when section header count is too high

Analysis

- Feature: Added experimental option for keeping dead code branches

- Feature: Setting to disable “pure” function call elimination

- Feature: Add BinaryView metadata about which libraries have applied type information

- Feature: Type extraction from mangled names is now optional

- Feature: Recognition of

thiscallandfastcallconventions on Win32 x86 - Improvement: Add support for indirect tailcall translation

- Improvement: Improved string detection

- Improvement: HLIL to other IL and assembly mappings

- Improvement: Resolve dereferencing a structure into accessing the first member

- Improvement: Create structure references for unknown field offsets

- Improvement: Propagate pointer child type to dereference expression

- Improvement: Template simplifier (from 2.3) now enabled by default

- Improvement: Range clamping to improve jump table detection

- Improvement: Add additional no-return function to Platform types

- Fix: Issue where function analysis could timeout unintentionally

- Fix: Invalid HLIL under some conditions

- Fix: Missing empty cases in switch statements

- Fix: HLIL graph when only default case falls through

- Fix: Crash when wide string ends without null at section boundary

- Fix: Fix hang in Pseudo C

- Fix: Crash when importing function type info from unknown type

- Fix: Constant propagation from writable memory for constant arrays

- Fix: Properly decode and render strings with BOMs

- Fix: Prevent demangler from making function types with single ‘void’ parameter

- Fix: Don’t allow demangled types to override Platform types

- Fix: MS Demangler fix order of multidimensional arrays

- Fix: MS Demangler properly set calling convention

- Fix: MS Demangler disambiguate int/long

- Fix: MS Demangler add implicit ‘this’ pointer when demangling ‘thiscall’

- Fix: MS Demangler demangle SwiftCallingConvention

API

- New API: Merge and split variables

- New API: Variable liveness API for determining soundness of merging/splitting variables

- New API: Components class and notifications

- New API: Get and set offset pointers

- New API: Implement .tokens property on HLIL

- New API: Function.get_variable_by_name

- New API: Get and delete for DebugInfo API

- New API: CallingConvention::GetVariablesForParameters

- New API: BinaryView.get_default_load_settings

- New API: Interaction.run_progress_dialog

- New API: Function.is_thunk

- New API: Notifications for Segment/Section Added/Updated/Removed

- New API: Function.caller_sites

- New API: HLIL_UNREACHABLE

- New Example: Feature map

- Improvement: Add progress callback to DebugInfo::ParseInfo

- Improvement: Implement missing APIs in BinaryNinja::Metadata

- Improvement: Add channel to core_version_info

- Improvement: DebugInfo.parse_debug_info returns a boolean

- Improvement: Many type hint additions and fixes

- Improvement: Python/C++ APIs to get registers, register stacks, and flags for LLIL

- Improvement: Allow DataVariable.name to be assigned a QualifiedName

- Improvement: Added a significant amount of C++ API Documentation

- Improvement: New theme for C++ documentation

- Improvement: Allow passing QualifiedNameType instead of QualifiedName to many functions

- Deprecation: BinaryViewTypeArchitectureConstant

- Deprecation: BNLogRegisterLoggerCallback

- Fix: Variable use/def API for aliased variables

- Fix: Platform.os_list

- Fix: DebugInfo.function

- Fix: issue where EnumerationBuilder couldn’t set the width of the enumeration

- Fix: BinaryView.get_functions_by_name to handle cases like

sub_main - Fix: Trying to delete incomplete LowLevelILFunction

- Fix: stack_adjustment.setter

- Fix: Type annotation & documentation for

define_auto_symbol_and_var_or_function - Fix: Issue where notification callbacks were not being called

- Fix: missing debugger_imported definition in PythonScriptingInstance

- Fix: Python exceptions when accessing functions with skipped IL analysis

- Fix: Class hierarchy of HLILRet

- Fix: Core parser not parsing

struct __packed foo - Fix: Ignore UI plugins when loaded in headless

Types

- Fix: Make

_Unwind_Resume()__noreturn

Architectures

- Armv7/Thumb2: Critical improvement to analysis of armv7/thumb2 call sites to respect callee function types

- Armv7/Thumb2: Proper lifting for Thumb2 LDM and STR with Rn not included in register list

- Armv7/Thumb2: Add lifting for SMULxx instruction forms

- Armv7/Thumb2: Fix lifting of certain uses of flexible operands (Thank you @ehntoo)

- Armv7/Thumb2: Fix crash on MSR banked instruction

- Armv7/Thumb2: Fix PC-relative alignment issue

- Armv7/Thumb2: Lift msr to basepri as __set_BASEPRI

- Armv7/Thumb2: Added vmov immediate lifting (Thank you @ehntoo)

- Armv7/Thumb2: Fix size of vstr storage (Thank you @ehntoo)

- Arm64: Corrected lifting of *ZR target register

- Arm64: Lifted load-acquire, store-release instructions

- MIPS: Properly handle delay slot rewriting with call targets (Thank you @yrp)

- MIPS: Lifted madd, maddu (Thank you @yrp)

- x86/x86_64:

int 0x29now ends basic blocks

Debugger

- Feature: Add support for remote Windows/macOS/Linux debugging

- Feature: Add basic support for iOS/Android remote debugging

- Improvement: New breakpoint sidebar widget icon

- Improvement: Remain in the debugger sidebar after launching the target or ending the debugging

- Improvement: Register widget refactor

- Improvement: Put the debugger breakpoints widget and registers widgets into a tab widget

- Improvement: Modules widget refactor

- Improvement: Status bar widget refactor

- Improvement: Add history entries support for target console and debugger console

- Fix: Windows x86 debugging

- Fix: Invert debugger icon colors and fix panel icon to not be grayscale

- Fix: Memory leak after using the debugger

Plugins/Plugin Manager

- Improvement: Prioritize plugin name in search filtering

- Improvement: More robust against offline networks and captive portals

- Improvement: Settings to allow disabling official and community plugin repositories

Enterprise

- Feature: Named and computer licenses are now available for Enterprise

- Feature: Project files may now be stored in folders

- Feature: The Enterprise server is now deployable with Docker Swarm

- Feature: The Enterprise server is now deployable with custom SSL certificates

- Improvement: Databases and files can now be downloaded directly from the files list without opening the database first

- Improvement: Syncing has been made significantly faster by avoiding unnecessary analysis cache downloads

- Improvement: A “skip” button has been added on initial launch to avoid waiting for server connection while offline

- Improvement: Changed the way Enterprise server deployments work to allow additional flexibility and customization

- Improvement: Enterprise client updates can now be downloaded and synced to the Enterprise server for only specific platforms

- Fix: The initial login window now correctly responds to other ways to close a window (e.g. Cmd-Q)

- Fix: Disabling plugins via the -p switch is now correctly supported in Enterprise

- Fix: Fixed multiple client crashes related to UI and networking

- Fix: The Enterprise server now correctly works with the compose sub-command included with newer versions of Docker

Miscellaneous

…and, of course, all of the usual “many miscellaneous crashes and fixes” not explicitly listed here. Check them out in our full milestone list: https://github.com/Vector35/binaryninja-api/milestone/16?closed=1

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh