2023-4-16 20:8:35 Author: perception-point.io(查看原文) 阅读量:22 收藏

Account takeovers (ATO), a form of cyber attack where unauthorized individuals gain access to a user’s account, have been prevalent for over two decades. With the increasing dependence on digital services and online transactions, the frequency of such attacks has only risen in recent years. Research has shown that the average cost of an account takeover, including impact and recovery costs, is approximately $12,000. Furthermore, the number of account takeover attacks has increased substantially in 2022 and is projected to only further grow in 2023.

In this blog we will delve into the kill chain of a compromised mailbox, tracing the steps from the initial phishing delivery to setting up inbox rules with deletion logic, and ultimately delivering malicious payloads to known contacts. Read on to learn more.

Figure 1: Compromised Mailbox Kill Chain

Step 1: Building The Phish

To gain access to a victim’s mailbox, an attacker typically needs to obtain the victim’s credentials. In the vast majority of cases, this begins with a mass phishing campaign initiated by the attacker. In rare instances, the attacker may acquire the credentials through information leakage or via malware that sends the data to their command-and-control center (C2).

Unfortunately, launching a phishing attack has become relatively straightforward. Attackers can typically generate a list of potential victims within minutes, create a phishing template (often impersonating a Microsoft or Google login page), and set up an email server to deliver the phishing emails. With this accomplished, the attacker can proceed to the next step.

Step 2: Going Phishing

The next step for the attacker is to construct a convincing phishing email and send it to the list of recipients they generated earlier. The email must be well-crafted to increase the likelihood that users will be tricked into clicking on the malicious link.

Typical phishing email subjects often contain language such as:

- Direct ACH Deposit Processed

- Expired Password

- Action Required

- Notification Alert

- Missed Voice Message

- New Fax Received

- Mail Server Quota Full

- Email Delivery Failure

- Reactivate Your Account

By using these types of subject lines, the attacker hopes to entice the user to open the email and take the desired action, such as clicking on a link or entering login credentials.

Figure 2: Common Phishing Template (March 2023)

Phishing email templates are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Attackers are now utilizing AI tools to generate templates that are nearly identical to the service they are impersonating, further increasing the likelihood that the recipient will fall for the scam.

For more information about the impact of AI in cyber attacks and defense, check out this blog!

Steps 3 to 5: Stealing Credentials

Since the steps involved in phishing attacks are well-known within the cybersecurity industry, we will not discuss them further in this blog post. Instead, we invite you to explore our other blog posts that delve deeper into the technical aspects of phishing:

7 Ways to Prevent Phishing and Advanced Anti-Phishing Techniques

How to Conduct a Phishing Attack in 5 Easy Steps

Step 6: Inside the Victim’s Mailbox

After gaining access to the victim’s mailbox, the attacker has limited time to extract sensitive data before being detected or locked out. At the same time, the attacker must establish rules that will help them execute the attack.

But how can you detect suspicious mailbox access before the attack progresses further? Microsoft’s audit logs can provide valuable insight into potential ATO events. Key properties to consider include:

- Subject: This refers to the subject line of the message that was accessed. If you discover access to subjects with words like “Password,” “Account,” “Invoice,” “Deposit,” or “Payment” appearing consecutively, it’s a strong indication that the attacker is seeking sensitive data.

- Operation: This property describes the operation performed by a user. In ATO events, common operations include “Set-InboxRule,” “New-InboxRule,” “Set-Mailbox,” and “New-InboxRuleForwardTo.” Attackers often use these operations to delete, conceal, or forward emails out of the organization.

- ClientIP: This refers to the IP address from which the login took place. Unknown or unauthorized IP addresses could suggest an ATO event.

- LoginStatus: A high number of failed logins followed by a successful login can indicate a brute force attack. Microsoft also includes a lockout event that occurs after a certain number of unsuccessful login attempts.

- UserAgent: This property contains data on the OS and browser used by the user to sign in. Therefore, if an organization is operating in a Linux environment with Edge and you discover a login from MacOS and Chrome, it’s something to watch for closely.

Step 7: These Are the (Inbox & Forwarding) Rules

Once the attacker has gathered the necessary information, they often create rules to help them carry out the attack. These rules usually involve either forwarding emails outside the organization or defining inbox rules. While forwarding rules are less common due to organization policies for data loss prevention (DLP) purposes, inbox rules are extremely prevalent in ATO cases.

Before launching a malicious attack, the attacker defines rules with deletion actions to avoid detection. The rules’ logic varies according to the type of attack they plan to launch. Here is an example of a malicious rule we recently encountered:

Figure 3: ATO Inbox Rule

In this case, there were a few indicators of malicious intent, including:

- Name: A suspicious name such as “ddd”, as opposed to default names like “Move all emails from XXXX to YYYY”.

- Mark as read: The rule marks all incoming emails that match the logic as read.

- Delete message: The rule deletes all incoming emails that match the logic.

- Content-based value: Here, the attacker used the property of searching for words in the email’s subject or body.

Breaking down the logic, we can see that the attacker is deleting all messages that contain the words [“Incomparable Incentives Awareness – Planning 2022;spam;hack;email;virus;delivery;undeliverable;failure;out of office;scam”].

Typically, attackers define rules that delete bounce-back messages. This is necessary, as a compromised mailbox is often used for mass delivery of malicious emails, resulting in many bounce-back and auto-reply messages returning to the mailbox. By creating this rule, the compromised user won’t know about the ongoing campaign.

Rules usually include the subject of the malicious email sent from the user’s mailbox, which, in this example, is “Incomparable Incentives Awareness – Planning 2022”. Since some of the recipients of the malicious email may suspect its intent and reply, the subject of the email becomes “Re: Incomparable Incentives Awareness – Planning 2022”. However, as seen in the rules’ logic, these replies are automatically deleted, ensuring the original owner of the mailbox remains unaware of the attack in progress.

Figure 4: Reply To The Malicious Email

Step 8: 2-Step Phishing, Malware Delivery & Thread Hijacks

After defining their rules, attackers leverage their attack using three main methods: 2-step phishing, malware delivery, or thread hijacking.

Two-Step Phishing

This type of attack requires two clicks to reach the malicious payload. With the growth in email security awareness, attackers are constantly finding ways to bypass filters. However, most email security systems extract URLs and check them, making it difficult for generic phishing pages to go unnoticed. To circumvent detection, attackers host links on trusted platforms such as Adobe, Evernote, SharePoint, Salesforce, and others. These platforms host another link or HTML file that redirects to the malicious pages. By using two-step phishing, attackers manage to evade most email security services that only extract URLs from the email and stop there to save resources and reduce costs. Without enabling advanced crawlers, the malicious payload will not be reached, and the email will not be incriminated.

Two-step phishing emails typically revolve around payment-related topics such as “Updated Payoff,” “Payment Copy,” “Incoming Document,” “Invitation To Bid,” “New Work Order,” or “Invoice Copy.” The subject and content of the sent emails will be business-oriented, as the compromised mailbox is for professional use. The trust already established with the sender makes the emails appear more credible to recipients, thereby increasing the perceived legitimacy of any shared document or invoice.

To make the emails appear even more legitimate, the attackers will use social engineering techniques such as including the compromised user’s signature. As a result, the phishing emails will not look like a generic phishing email.

Here are some examples of emails that may be sent by a compromised user in a two-step phishing attack:

Figures 5 & 6: 2-Step Phishing Emails

Figure 7: The Malicious Redirect Hosted on SharePoint

Figure 8: A Malicious .html File Hosted on Evernote

If the recipients fall for the phishing attempt, the attacker gains access to their mailboxes, leading to an infinite loop of account takeovers. In the last quarter alone, we caught over 20,000 emails involving two-step phishing from compromised users, and we expect this number to grow significantly in Q2 2023. This attack is an easy way for attackers to gain access to multiple organizations at once.

To learn more about recent trends in two-step phishing, check out this blog: One for the Show, Two for the Money

Malware Delivery

After gaining access to a victim’s mailbox, the attacker may launch a mass malware delivery attack. Attackers often use information-stealing malware, sending it to all of the victim’s contacts, whether they are inside or outside the organization. Typically, this is done by replying to an existing email with a malicious executable attached and including a message such as, “Hi, I just sent you a document, can you take a quick look?” in order to lure the recipient into opening the attachment.

Figure 8: OneNote Dropper Delivery

Thread Hijack

A thread hijack is a type of attack classified under BEC (Business Email Compromise). Essentially, it involves an attacker injecting themselves into a legitimate conversation for malicious purposes.

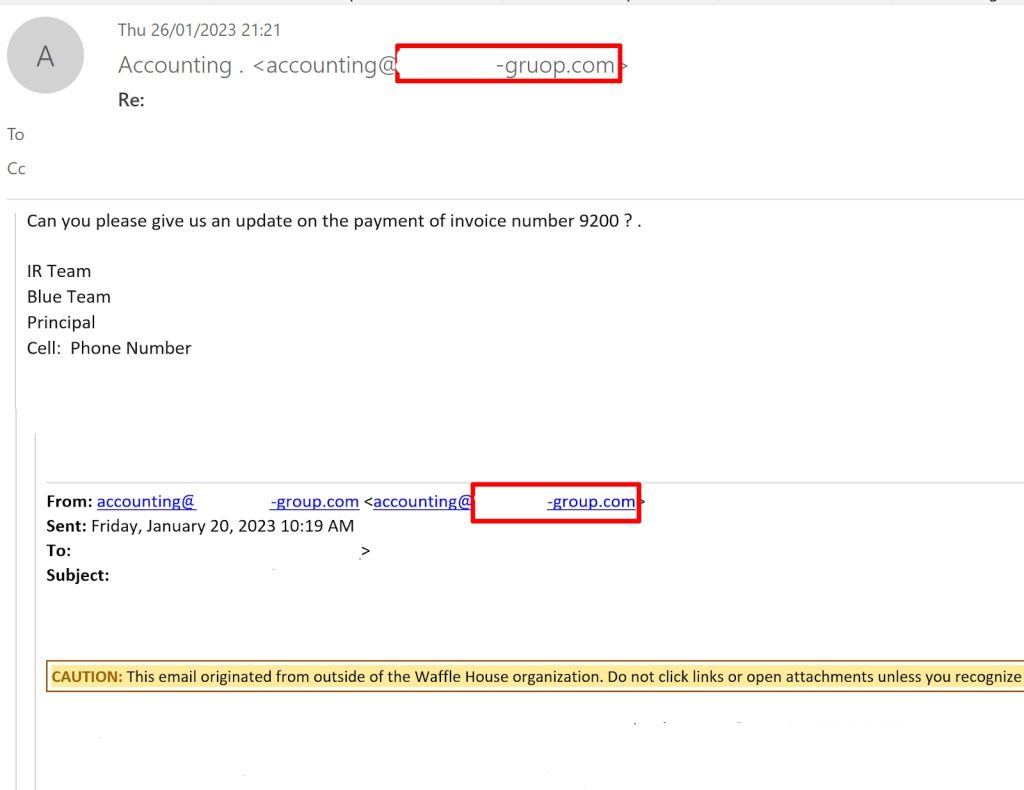

After gaining access to a victim’s mailbox, the attacker searches for payment-related emails that contain information about bank accounts, invoices, and deposits. Once a successful attempt has been made, the attacker hijacks the thread and continues the conversation from a newly registered domain that resembles the original domain.

For example, if the attacker found an email discussing a bank account coming from “blueteam-group.com,” they would register a new domain called “blueteam-gruop.com” and request to change the bank details. The target may find it difficult to notice the difference and will most likely fall victim to the scam. These look-alike domains are privately held and are typically registered on sites where domains can be purchased with cryptocurrency.

Figure 9: Threat Hijack Email

This type of attack has the potential to be highly successful and can have significant financial repercussions for organizations. We have encountered a few cases in which we managed to block these emails, but admin users still released them, convinced these emails were authentic. Even highly trained security analysts may find it difficult to recognize this type of attack.

Conclusion

ATO attacks are a growing concern for organizations of all sizes, as they can have severe consequences including financial losses, data breaches, and reputational damage. We recommend taking the following steps to mitigate your organization’s risk:

- Implement strong authentication methods such as multi-factor authentication.

- Monitor accounts for suspicious activity and unusual behavior.

- Educate employees on phishing and social engineering tactics to prevent unauthorized access to credentials.

- Regularly update and patch systems to address vulnerabilities.

- Employ an advanced email security service to detect and block malicious emails and attachments before they reach users’ inboxes.

- Establish an incident response plan to quickly respond and remediate the impact of an ATO attack.

For more information about how Perception Point can help your organization prevent ATO attacks, contact us here.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh