2020-11-1 04:11:0 Author: taosecurity.blogspot.com(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

There's a good chance that if you're reading this post, you're the member of an exclusive club. I call it the security one percent, or the security 1% or #securityonepercent on Twitter. This is shorthand for the assortment of people and organizations who have the personnel, processes, technology, and support to implement somewhat robust digital security programs, especially those with the detection and response capabilities and not just planning and resistance/"prevention" functions.

Introduction

This post will estimate the size of the security 1% in the United States. It will then briefly explain how the security strategies of the 1% might be irrelevant at best or damaging at worse to the 99%.

A First Cut with FIRST

It's difficult to measure the size of the security 1%, but not impossible. My goal is to ascertain the correct orders of magnitude.

One method is to review entities who are members of the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams, or FIRST. FIRST is an organization to which high-performing computer incident response teams (CIRTs) may apply once their processes and data handling meet standards set by FIRST.

I learned of FIRST when the AFCERT was a member in the late 1990s. I also assisted with FIRST duties when Foundstone was a member in the early 2000s. I helped or sponsored membership when I worked at General Electric in the 2000s and Mandiant in the 2010s. I encourage all capable security teams to join FIRST.

Being a FIRST member means having a certain degree of incident response and data handling capability, and it signals to the world and to other FIRST teams that the member entity is serious about incident detection and response.

As of the writing of this post, there are 540 FIRST teams worldwide. Slightly more than 100 of them are based in the United States.

To put that in perspective, there are less than 4,000 publicly traded companies in the US. That means that even if every single US FIRST member represented a publicly traded company -- and that is not the case -- FIRST representation for US publicly traded companies is only 2.5%.

Beyond FIRST

Some of you might claim FIRST membership is no big deal. My current employer, Corelight, isn't a member, you might say.

Perhaps you could argue that for every US FIRST member, there are 9 others which have equivalent or better security teams. That would increase the cadre of entities with respectable detection and response capabilities from 100 to 1,000. That would still mean an estimate that says 75% of publicly traded US companies have sub-par or non-existent security programs.

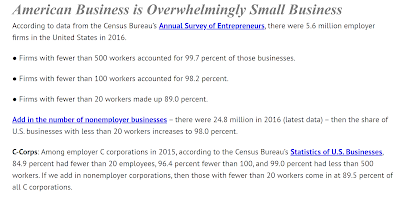

Remember that we've only been talking about a population of 4,000 publicly traded US companies. The US Small Business and Entrepreneurship Council estimates that there were 5.6 million employer firms in the United States in 2016. Let's sadly reduce that to 4 million to account for the devastation of Covid.

(This reduction actually makes the situation actually look better for security, as terrible as it is either way. In other words, if I used a denominator of 5.6 million and not 4 million, security estimates would be 40% worse.)

|

| Small Business and Entrepreneurship Council |

Let's be really generous and assume that only 1 in 100 of those 4 million businesses have any sensitive data. (That's again very generous.)

That leaves us with 400,000 entities with data worth defending. (Again, all of these estimates make it look like we're doing better than we actually are. The reality is probably a lot worse.)

Remember that we only had 100 US teams in FIRST, and we assumed an incredible 10-to-1 ratio to add another 900 non-FIRST organizations to the list of entities with decent security.

Now let's be generous again and assume a 4-to-1 ratio, such that for every 1 team in the publicly traded world there are 3 in the private world that also have decent security.

This creates a total of 4,000 US organizations with decent security, out of 400,000 that need it. Those 4,000 are the security 1%.

If you think of the "best of the best," there's probably only about 40 US security teams that qualify as global leaders and innovators. These are the teams that can stand toe-to-toe with most foes, and still struggle due to the nature of the security challenge. You and I could probably name them: Lockheed Martin, Google, General Electric, etc.

That group of 40 is the 1% of the 1%, being 40 of the 4,000 of the 400,000. These 40 are the US .01%.

If you think I'm being too conservative with only 40 teams, then feel free to increase it to 400. I'd be really curious to see someone compile a list of 400 world-beating security teams. That would still mean that US group of 400 is the .1%.

Sanity Check: A Few Statistics

To give you a sense of my numbers, and whether they are of the right order of magnitude at least, here are a few statistics:

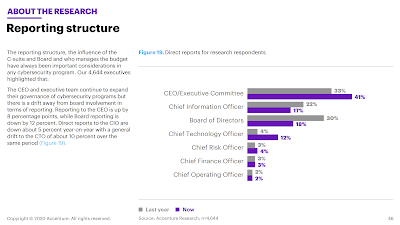

1. The 2020 Accenture Security Third Annual State of Cyber Resilience Report featured responses from 4,644 "executives," This is the same order of magnitude of my estimates here, diluted due to a global perspective. (In other words, there are actually less US executives responding to this survey due to the global respondent pool.)

|

| 2020 Accenture Security Third Annual State of Cyber Resilience Report, p 46 |

2. The 2021 PWC Global Digital Trust Insights Report featured responses from "3,249 business and technology executives around the world." This is again the same order of magnitude, again diluted due to global responses.

|

| 2021 PWC Global Digital Trust Insights Report, Web summary |

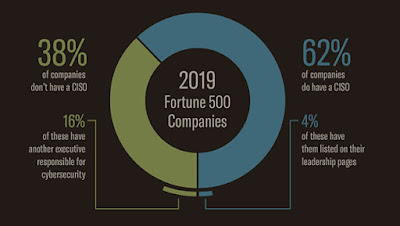

3. A 2019 report by Bitglass found that 38% of the Fortune 500 do not have a CISO. That's 190 publicly traded companies! Hopefully it's less in 2020. Let's be crazy and assume the CISO count is 400 out of 500?

|

| 2019 Bitglass Report |

4. The Verizon DBIR featured reporting from 81 entities, the highest number in the history of the report. I do not know how many are in the US, but it's obviously less than 100, so the order of magnitude is again preserved. In other words, of the 4,000 capable security organizations in the US, less than 2.5% of them contributed to the DBIR. That would be less than 100, or the number of US FIRST teams.

|

| 2020 Verizon DBIR Report |

Remember that my focus here is the United States. This means the numbers from PWC, Accenture, and Verizon need to be reduced because they represent global audiences. However, the original FIRST count of roughly 100 American entities, and the statistic about the Fortune 500, which is just American companies, are already appropriately sized.

Security and the One Percent

What do these numbers mean for security?

Speaking first just for the US, it means that most of the conversations among security practitioners on Twitter, in mailing lists, during Webinars, within classes, and other gatherings of people take place within a very small grouping. These are the 1% that are part of the roughly 4,000 entities in the US that have a decent security capability.

If those are the 1%, it means that the 99% are not included in these discussions.

This means that free threat intelligence, or free classes, or free post-exploitation security tools, or other free capabilities mean nothing, or almost nothing to those 99% of organizations that do not have security capabilities, or whose capabilities are so low or stretched that they cannot take advantage of whatever the 1% offers.

An Analogy: Personal Finance

I almost became a certified financial planner. Had I not secured a job in the AFCERT, I planned to separate from the Air Force, earn my CFP designation, and advise people on how to manage their assets and prepare for retirement.

I've come to realize that discussions I witness in the "security community" are like the discussions I see in the finance community. It requires taking a big step back to appreciate this situation.

People at the 1% level in finance want to know how to manage their stock options, or how to save money for their child's college tuition through specialized savings vehicle, or, at the highest ends, how to move assets throughout "Moneyland" in pursuit of ever lower taxes.

These concerns are light-years away from the person who has a few dollars saved in an employer-provided 401(k) program, or who has little to no savings whatsoever.

The Consequences of the Security One Percent

So what's the big deal?

The consequence of the existence and mindshare dominance of the security 1% is that the strategies and tactics they employ may work for the 1%, but not the 99%.

I'm not talking about the "rich" preying on the "poor." That's neither my message nor my philosophical outlook.

Rather, I mean that methods that the security 1% use to defend themselves are irrelevant at best to the 99%, and damaging at worst to the 99%.

An example of irrelevance would be providing free indicators of compromise (IOCs) or other forms of threat intelligence. It's well-meaning but ultimately of no help to the 99%. If an entity in the 99% has a rudimentary security capability, or essentially zero security capability, threat intelligence is irrelevant.

An example of damage would be publication of post-exploitation security tools, or PESTs. The 1% may have the ability to use such tools to equip their red or penetration testing teams, determining if the countermeasures implemented by their blue team can resist or detect and respond to their simulated and later actual attacks. The 99%, however, have little to no ability to leverage PESTs. They end up simply being victims when actual intruders use PESTs to pillage the 99%'s assets.

Conclusion

Readers can argue with my numbers. These are estimates, yes, but I believe I've gotten the orders of magnitude right, at least in the US. It's probably worse overseas, especially in the developing world.

The point of this exercise is to propose the idea that the benefits of certain activities that may accrue to the 1% may be, and likely are, irrelevant and/or damaging to the 99%.

In brief:

I challenge the security 1% to first recognize their elite status, and second, to think how their beliefs and actions affect the 99% -- especially for the worse.

As this is a wicked problem, there is no easy answer. That may be worth a future blog post.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh