CloudFox helps you gain situational awareness in unfamiliar cloud environments. It’s a command line tool created to help penetration testers and other offensive security professionals find exploitable attack paths in cloud infrastructure. It currently supports AWS, but support for Azure, GCP, and Kubernetes is on the roadmap. Watch our video for a quick demonstration of how we might use CloudFox on our cloud penetration tests.

Automating the Enumeration Process

The main inspiration for CloudFox was to create something like PowerView for cloud infrastructure. A collection of enumeration commands that illuminate attack paths even for those relatively new to cloud penetration testing. To do this, we codified our many sed/awk/grep/jq incantations into a tool that is portable, modular, and quick. Our primary audience is penetration testers, but we think CloudFox will be useful for all cloud security practitioners.

CloudFox doesn’t perform any state changing operations

All CloudFox commands are read-only (i.e., get, list, describe), and it’s intended to be used by an IAM principal with the SecurityAuditor or similar policy attached. Unfortunately, the SecurityAuditor, ViewOnlyAccess, and even ReadOnlyAccess policies don’t allow all of the permissions that CloudFox uses, so we created a custom policy that you can attach in addition to SecurityAuditor to ensure CloudFox can query the information it needs. This policy can be found here. That said, no matter what permission you run CloudFox with, you can rest assured that nothing will be created, deleted, or updated.

CloudFox helps you get a lay of the land

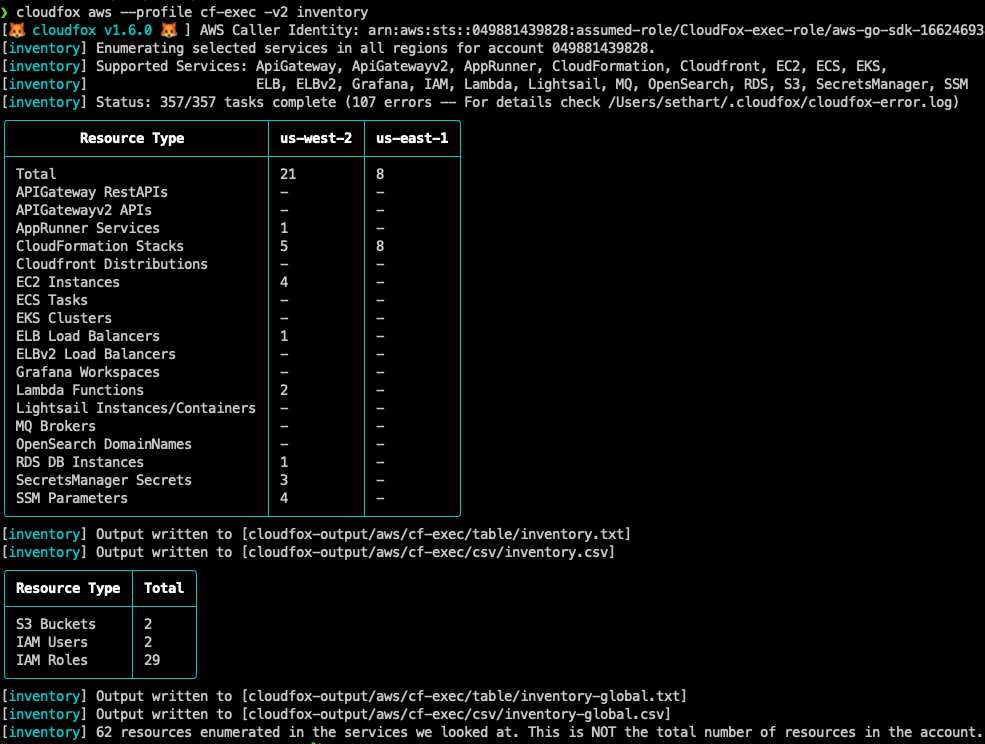

The first command you’ll likely run in a new environment is inventory. Inventory helps you figure out which regions are used in the target account, and it gives you a rough size of the account by counting the number of resources in some of the most common services.

CloudFox groups checks when possible

In some cases, similar requests are grouped together. This is usually based on how you would use the result of the command. Rather than one command that enumerates ELB Endpoints and another one that enumerates CloudFront endpoints, we have one command called endpoints that enumerates the service endpoints for multiple services at the same time. That way you can take the output of the endpoints command and feed into application fingerprinting and enumeration tools like Aquatone, gowitness, gobuster, ffuf, etc. This same pattern is used whenever possible.

CloudFox creates loot files

CloudFox’s table and csv output options allow you to wrap your head around the cloud environment relatively quickly, but we think the most helpful thing CloudFox does is create usable loot files for you. The files can either be imported into other tools as input, or they show you what to do next.

When you run the instances command, you get a file with all of the public IPs associated with EC2 instances, and another file with all of the private IPs. These files can be used as input for your service identification tools such as nmap.

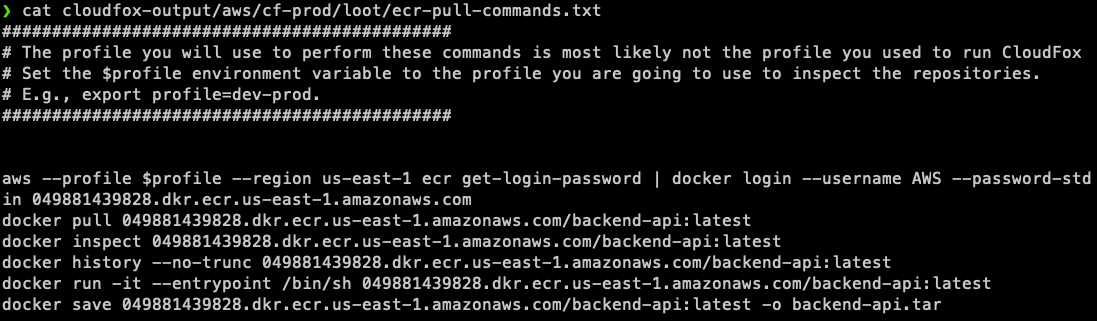

Some loot files are not intended to be input; rather, they give you commands that you can run from the terminal to investigate the identified resources. For example, when you run the ecr command, it gives you a loot file that tells you exactly how to pull each image from ECR, and what to do next:

For the full documentation on all the commands, please refer to our wiki.

Connecting the Dots

Before we wrap up, we wanted to share an example that illustrates how we use CloudFox on cloud penetration tests at Bishop Fox to automate tasks that take a lot of time using the AWS console or other tools.

Let’s say you ran the env-vars command and found RDS credentials in a Lambda environment variable:

We have RDS credentials, but where is that RDS database and who can access it? Let’s see what the endpoints command has to say. We can run the endpoints command again, but we don’t have to, because all command output is automatically saved to disk:

CloudFox found a single RDS database, and better yet, it’s publicly accessible. We don’t even have to be on the internal cloud network to access it if we have the credentials (and we do have them thanks to the env-vars command). Let’s use those credentials to see if we can connect:

Excellent! So, we connected to the database (and eventually found sensitive PII), but the burning question is now: Who the heck has access to that RDS password saved in the Lambda environment variable – in other words, who can exploit that misconfiguration? Is it just a few admins? If so, that’s still worth mentioning to our client, but not really a huge deal. But what if it’s a user who should NOT have direct access to the data in that database, like the interns?

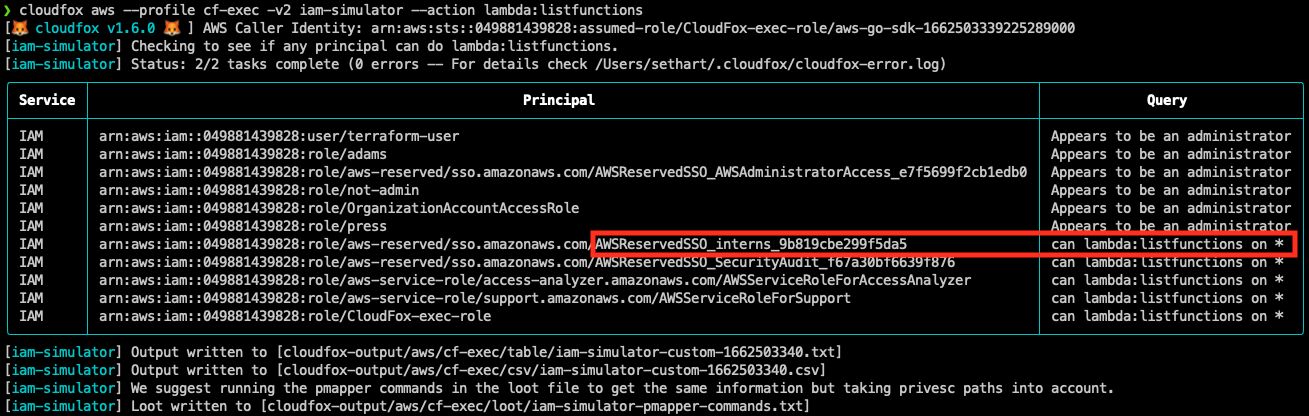

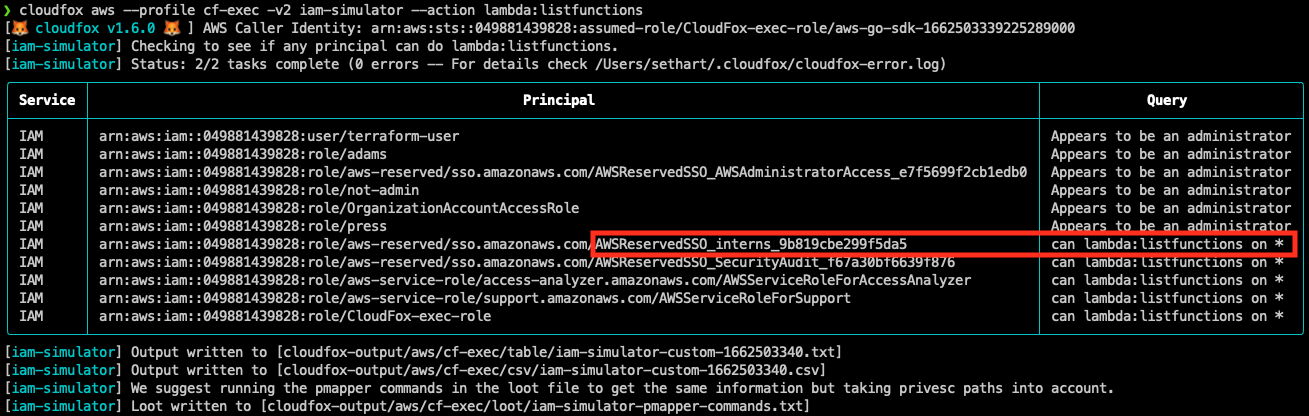

Let’s use the iam-simulator command to find out by asking it who can list perform the lambda:ListFunctions action on all resources:

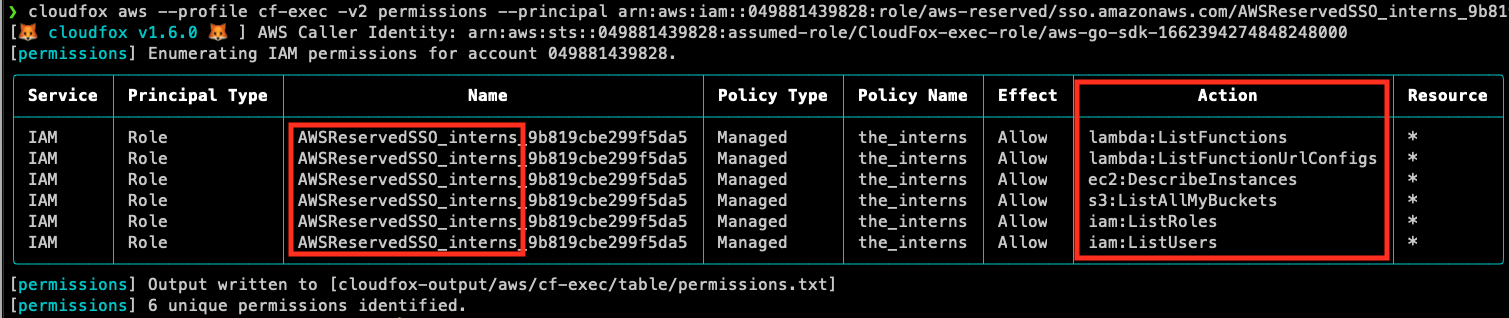

Everyone in this list can view the environment variables for all Lambda functions, but the one that sticks out is the AWS SSO role for interns. Let’s dig into this role a little deeper, using the permissions module.

It’s pretty apparent the interns SSO role is only supposed to have limited read access to this account, but as it turns out, read access to Lambda functions inadvertently gave them read/write to the production RDS database which contains the most sensitive data in the environment. This is something our fictitious client will want to know about!

Homework

If you’d like to see the power of CloudFox in a lab environment, run it against the scenarios in the excellent CloudGoat project. Before the public release of this blog post, we spun up several CloudGoat scenarios and were pleased to learn that we could fully complete the scenarios using nothing other than CloudFox and the AWS CLI.

Conclusion

Finding attack paths in complex cloud environments can be difficult and time consuming. There are a lot of tools that help you analyze cloud environments, but many of them are more focused on security baseline compliance rather than attack paths. We hope you find that CloudFox can automate the boring stuff and help you identify and exploit latent attack paths more quickly and comprehensively.

Subscribe to Bishop Fox's Security Blog

Be first to learn about latest tools, advisories, and findings.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh