I’ve worked in software security for a long time. One of my earliest blog posts cited my HackerOne profile as a data point for taking my opinion seriously, but I never really considered myself a “bug bounty hunter”. I’m basically a software security expert that works in the cryptography (NOT cryptocurrency) space by day, cryptography blogging furry by night.

Credit: LvJ

Sometimes, when I wanted to report a vulnerability to a product, service, or software project, I would be instructed to disclose my findings through a bug bounty platform such as HackerOne or Bugcrowd. When this happens, I might look around to see if any of the other programs interest me, but they rarely do.

As a consequence of this conduct, I’ve accrued a few thousand dollars over the years from both platforms. That may sound like a lot of money, but it’s basically a mobile phone bill’s worth of bounty money over 3+ years.

Most of my earnings went into private, direct action donations to people that need it (including helping LGBTQIA+ folks escape Russia). This was always done under the terms of “pay it forward” (because I don’t want to be paid back, or hold any leverage over people for once being in a vulnerable situation).

My point being: My participation in these platforms was never about the money for me. I’m a very curious person and want the products, services, tools, and code that people use to be as secure as possible so they don’t get hurt.

My ethical obligations as a security researcher are solely to protect users. I have no ethical obligation to protect the reputations of any vendors or companies, except as a byproduct of protecting users.

If immediate full disclosure will clearly better protect users, I will prefer that over coordinated disclosure or non-disclosure. However, I rarely have the visibility into the full scale of a project’s deployment, and therefore it’s difficult to ascertain what disclosure policy is best, so I generally default to coordinated disclosure if reasonably practical.

Past Friction With Bugcrowd

Earlier this year, my friends started a business. As their friend and technology consultant, I thought I’d compare password managers before making a recommendation for them to use. However, rather than just compare marketing copy and an Excel checklist of features, I thought I’d use my existing cryptography knowledge to study them in detail.

Most of the password managers have a bug bounty program on Bugcrowd. Every password manager can effectively be reverse engineered with dex2jar + Luyten (or, for browser extensions, Ctrl + Alt + L in a Jetbrains IDE to beautify the JavaScript code).

This presented a unique opportunity: Not only could I evaluate each password manager’s cryptography implementations, but if I did find any interesting bugs, I could evaluate their responses to security researchers as well.

Aside: Without getting into the details of what I’ve found and disclosed, 1Password is an excellent choice and treat security researchers with respect.

Can you guess what happened next?

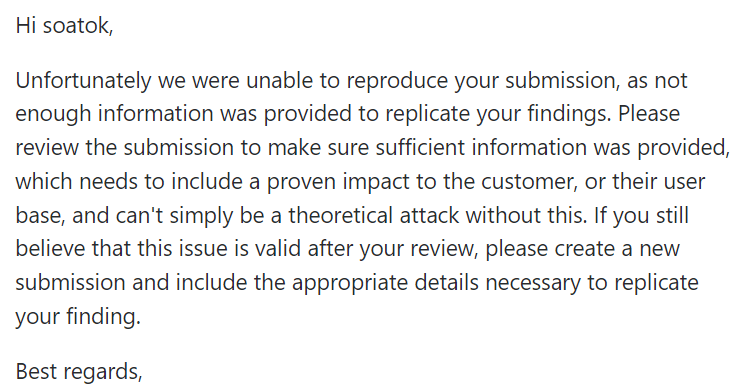

This is their standard response to the kinds of reports I’d write, which included:

- A direct link to the source code that was vulnerable

- A description of why the particular snippet was vulnerable

- References to other publicly available research into congruent side-channel attacks in similar software

- A patch, accompanied by some writing that explains how/why it fixes the leakage

But my reports didn’t include exploit code, because exploit development is not my specialty, and it’s ludicrous to expect me to invest hundreds of hours of my life into learning and mastering an extremely advanced skill just to get a bug report that already contains all of the above to not get rejected by a triage team.

— Ryan Castellucci (@ryancdotorg) June 14, 2022This type of exploit is extremely time consuming to produce, and doing so does not guarantee payment.

The security researcher then, out of frustration, throws up their hands and either decides to sit on the vuln, or simply publish it – neither of which is a good outcome.

Consequently, I reached out to Bugcrowd support to complain that their standard processes and runbooks were failing. Cryptographic issues are already hella specialized, and expecting any reports to also include an orthogonal specialty (while demanding that only solo researchers report bugs, rather than teams) is frankly unreasonable.

After about four or so more rejections (which were often overriden by the program owners; i.e. the actual vendors), I started doing something a bit snarky: I’d include a “proof of concept” that merely demonstrated that their function was variable-time based on the bit patterns of the inputs. This isn’t an exploit PoC like Bugcrowd demanded, but it was enough to satisfy the box-checking mentality at work.

(If any of the bug bounty programs I reported issues to is reading this: Yes, that’s why I included such a stupid and pointless “proof of concept” in my reports. I wasn’t trying to insult your intelligence, I promise!)

Enter Xfinity Opensource

The Xfinity Opensource program on Bugcrowd (alternative archive) ostensibly exists for Xfinity (read: Comcast) to give back to the open source community.

Their program advertises the JSBN JavaScript big integer library as “in scope”; presumably because they rely on it for some sort of cryptography purpose (most likely RSA or SRP, but who knows?). The original JSBN project website uses the title, “RSA and ECC in JavaScript,” so the intent was clearly to be cryptographically secure.

When I wrote my guide to side-channel attacks and constant-time algorithms, and included a TypeScript implementation, I was vaguely aware of JSBN and suspected it wasn’t secure. But I also assumed it was legacy code, or abandonware, that only served as a crypto.subtle polyfill for old browsers. Seeing it included in the project’s scope here changed my mind and I decided to dive into their implementation.

On April 8, I disclosed my findings through the Xfinity Opensource bug bounty program on Bugcrowd.

Two days later (April 10), it was closed by a Bugcrowd employee as “not applicable” because I didn’t include exploit code. I pushed back on this, and requested disclosure. My reasoning for this request is simple: If it’s actually not applicable, then you’ve determined it’s safe to disclose. Otherwise, it’s actually applicable, and you’re just being weirdly hung up about a checkbox item.

Bugcrowd said they would check with the Comcast team and update me accordingly. On May 6, a member of the Comcast PSIRT responded to the ticket.

An excerpt from the response (from my email records)This program is intended to be supportive and beneficial to the open source community at large, and we do not have any direct control over these repositories. However, we do work directly with the maintainers concerning any security reports, bounties, and disclosures. In this case, we have contacted Andy to inform him of your report. Further, since he is the maintainer, we make the disclosure request decision with his input.

As soon as we are able to discuss with the JSBN maintainers, we will follow up on a disclosure determination.

Today, on June 14, they denied the disclosure request, reasoning that since they don’t actually maintain the repository, it’s really not their place to disclose anything through the Bugcrowd platform. In their rejection, the same PSIRT member said:

Since we don’t author or maintain this code, we do not have any authority to grant a disclosure request. However you might be able to engage with them on the repository, or develope a further PoC that would enable validation of your claims.

From the Comcast employee (emphasis mine)

So I decided to engage with them on the repository.

Banned from Bugcrowd

Setting aside the comical use of “your Github blog” to describe the issue tracker for JSBN (which is the repository in which I was instructed to engage with the maintainer), this sort of action doesn’t actually make sense for the kind of security research I do.

Bugcrowd’s vendors have mostly agreed to a Safe Harbor clause. This means they will not prosecute anyone who acts in good faith to report vulnerabilities through the Bugcrowd platform. This is a good thing to have if you’re sending packets over a network, lest the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1988 (or congruent laws abroad) bit you in the posterior. But if you’re only reverse engineering software that runs on your own machine and critiquing the source code, the CFAA doesn’t really apply, and Bugcrowd has no real leverage over what you do with your expert opinions about how vendors’ software operates (since you don’t need a safe harbor to avoid procecution).

Also worth noting: Neither JSTOR nor MIT wanted to prosecute Aaron Swartz, but that didn’t stop federal prosecutors from doing so anyway, and he’s no longer with us. So, y’know, keep that in mind with the Safe Harbor agreements. Bastards will be bastards.

After I pointed out that a) a takedown would be pointless due to an archive already existing and b) I was instructed to engage with the maintainer via the repository (which is exactly what I did), the Bugcrowd support employee responded with a weird demand.

Pay attention to the wording of that second paragraph. This is the kind of language used by manipulative ex-partners or power-tripping school principals.

At first glance, because I do not operate archive.today nor have authorized access to their servers, I thought Declan was demanding me to hack into the archive site to remove the entry. That would be a federal crime under the CFAA. But it turns out I was mistaken, and he instead wanted me to leverage a “abuse report” mechanism to remove the archived copy.

I find it comical that anyone working in security hasn’t heard of the Streisand Effect in 2022, but maybe Declan is one of today’s lucky 10,000?

Of course, I’m not one to give into bullies, so I responded in the only appropriate fashion.

The entire saga was captured on a Twitter thread, which is probably how many of you found this write-up in the first place:

What Happens Next?

Since I’m banned from Bugcrowd, if I ever discover another security issue in a project that uses Bugcrowd exclusively for vulnerability management, I have no other recourse than immediate public disclosure.

(If you use Bugcrowd, maybe make sure your security@ is actively staffed so I can contact your company directly? Or use the new Security.txt standard.)

Since I don’t send packets to networks (what they call “website testing” or “API testing”), being excluded from Bugcrowd’s Safe Harbor negotiations won’t put me in any additional legal peril, so there’s no chilling effect at play.

However, other security researchers may depend on the Safe Harbor negotiations to avoid prosecution, and may be susceptible to such leverage when a disagreement with Bugcrowd employees occurs.

What I find most alarming is the attempt at emotional blackmail in these communications. The cavalier attitude towards post-disclosure censorship is noteworthy too.

If the nature of my security research was legally perilous like, presumably, most of their researchers, then this kind of manipulation would probably be even more pronounced. And that’s frankly alarming to me.

I can imagine how strong the implied legal threats would become, but I will not speculate publicly on such matters.

Regardless of how Bugcrowd management tries to respond to this issue, I won’t be returning to their platform.

I will never again support any bug bounty platforms that allow its employees to attempt to exploit or manipulate people less privileged than me into compliance. This is unacceptable and unethical.

Update (2022-06-16): Bugcrowd Responds

Bugcrowd’s Founder/CTO had reached out to me via Twitter DM, and after a productive discussion, tweeted the following:

— cje (@caseyjohnellis) June 15, 2022for those playing along at home: @bugcrowd definitely didn't do its best work here, and we're aware

we're digging into how to fix and avoid it in the future – and i've been speaking with @SoatokDhole to understand better and to apologize https://t.co/QRZQHHQdYR

Casey wasn’t blowing smoke with this tweet: He actually did what he said.

Specifically, he apologized up front and asserted that this escalation should not have ended the way it did, while promising an investigation into what went wrong, how to resolve it, and how to avoid it in the future; but also, to ask if there was any feedback or suggestions I wanted to share that weren’t already stated.

Quick aside: There’s basically no way for a C-level executive to respond to an incident like this without someone in the audience claiming it’s “mere damage control and self-preservation of the company’s reputation”. But I’ve actually received those sorts of communications throughout my career, and let me tell you, they are not at all written like this:

Naturally, I responded in kind (albeit with a few spelling errors).

Hi Casey,

I’m generally empathetic to the position most triage teams working in vulnerability management find themselves in: There’s a lot of noise, and extracting the signal is extremely difficult to automate. Ego and emotions can run high (usually on the reporters’ side, I’d wager), and it can create a lot of unnecessary conflict. I’ve seen the kind of trolling and spam that you’re plagued with, and I probably don’t know the half of it.

None of these observations are your failures, but problems that are extremely difficult to mitigate. I’m only mentioning them because: It’s for those reasons that I generally err on the side of patience and will prefer to escalate issues rather than blast them publicly except as a last resort.

I’ve made suggestions in the past. One pertinent to the issue I reported is: Create a distinct category for cryptographic side-channel issues, specify a different runbook for evaluating them.

That would alleviate the underlying friction and root cause for this entire mess. Everything downstream could have been prevented if there was an internal process of “Wait, this is a side-channel? Let’s ask our person knowledgeable in side-channels if it’s valid or not if we’re not immediately sure.”

So if you take nothing else away from this incident, that would be the most valuable and easy-to-mechanize lesson to learn.

I don’t know Declan’s history or experience. The way they responded signaled to me a story that might not be true, especially if they were already just having a bad day before this escalation. But the story it tells is one of bad habits; of exercising coersion against people that lack the privilege to resist the communication style they employed (which was very manipulative).

Now, I’ve received no special training against social engineering, beyond being LGBTQIA+ and a member of a community that gets targeted a lot by terrible people. It’s mostly because I’m financially independent and never send packets to anyone else’s machine through the course of my work (and therefore side-step any need for a Safe Harbor) that I was able to say “No” to the messages I received in that thread. My only concern is, “If this is how Declan usually handles escalations, how many people weren’t in my position?” and “How nasty were these coersion attempts in the past?”

If your goal is to regain trust with the part of the community that is aware of this incident, I would focus on answering those concerns too. And not just for Declan, but for all responders. If this is normalized, I implore you to disrupt it. Basic nonviolent communication strategies can go a very long way.

As someone who has been to Queercon at DEFCON for several years, I am grateful for the good you do for the community. This incident could have happened anywhere; how you respond is what reveals your company’s true character to the world. Although I have no interest in returning to the platform, I will certainly be watching before I decide my final opinions.

Thanks,

Soatok

And so, that’s generally the tone of the conversation that’s been happening behind the scenes.

Instead of regurgitating the entire Twitter DM conversation in public, though, I think it’s a better use of everyone’s time if I instead focused on the causes and effects rather than what was said.

Why Did This Go Sideways in the First Place?

When I posted my acknowledgement of “go engage with the maintainer in the repository”, I had repeated their suggestion back to them with a little bit of snark. Then I shared a link to the GitHub issue in a follow-up comment. (After all, I could have just done that months ago.)

To the best that we can figure, Declan misinterpreted the snarky echo as some sort of threat, and then posting a link to a GitHub issue tracker as if it were “making good” on said threat, rather than what was intended: Being mildly miffed about the whole situation, and expressing exasperated humor at an awkward-in-practice bounty program scope.

Mea culpa. I didn’t imagine their interpretation at the time, and in hindsight, it’s an understandable confusion.

But also! That could have been cleared up with a simple question: Why?

- “Why are you doing this?”

- “Doing what? They told me to engage with the maintainer on the repository.”

- “Oh. But you just said […], then published to GitHub. Doesn’t that imply […]?”

- “Oh, no, that’s not what’s happening here. […explanation…]”

There were many more failures that occurred after the initial communication.

What About All the Threatening Letters?

The smoking gun is, “GitHub blog”, really.

Clearly, the first email they sent out was generated from a template. The template made some assumptions that weren’t applicable to the situation.

Speculation: It was probably generated in response to researchers publishing blog posts about their [literal] exploits and not realizing the terms they agreed to in order to make use of the Bugcrowd platform.

To not put too fine a point on it: The template they used is utter garbage and needs to be replaced.

The follow-up emails? I still have no idea, but I’ve received multiple apologies from Bugcrowd leadership for them, so I’m not going to dwell on them unnecessarily.

What Is Bugcrowd Doing About This?

From what I’ve been told by their Senior Director of Security Operations:

- They’re updating their SecOps runbooks to include specific (and customizable) rules for every VRT category. This was already a thing they were doing (targeting August), but in direct response to my feedback, they’re prioritizing cryptography to ensure it’s handled appropriately.

This addresses the root cause for this issue, and also alleviates the additional friction.

- They’ve acknowledged a gap in their understanding of cryptography and are seeking to address this blind spot. This may mean hiring someone with cryptography expertise to fill in the gaps on their side and ensure reported issues are correctly understood.

- The triage team and their technical writer are immediately overhauling their outbound communication templates to eliminate the kind of toxic language that was used. To quote Michael:

“My intent is to get a similar set of responses, and a writing style guide like we did there established in support, but with more of a focus on mutual respect between all involved parties (where those other templates focus on conveying impact). The key takeaway – as a researcher, what was communicated to you wasn’t respectful, and it didn’t appreciate that you were acting in good faith. It’s important to emphasize here that we very much do have a process where all bans need to go through multiple teams for approval and technical review before they get enacted. Not only was that step bypassed here, but the core issue wasn’t fully investigated or understood before doing outreach. As Casey has publicly stated – this absolutely wasn’t our best work, and we are highly disappointed in what happened here.”

Michael concluded his DM outreach with this:

At this point, I’m waiting to see how these changes manifest in the platform and the culture of their employees before I finalize my opinion on Bugcrowd as a company.

I think people who are taking this incident as an excuse to dogpile on Bugcrowd are missing an important point:

Mistakes happen, even extremely bad ones. Nobody’s perfect. (I’m sure as hell not!) We shouldn’t demand that people or companies have flawless records without any blemishes in their entire history, or bust. That’s toxic perfectionism.

What matters more to me isn’t whether or not this incident occurred, but how the company responds to it. And so far, if Casey or Michael and I were to swap places, the way they’ve communicated with me is how I’d want to be able to communicate with them. They’ve been far more transparent with me than I feel comfortable publishing here, and that’s refreshing.

That being said, it’s extremely unlikely that I will choose to return to their platform as a researcher. Trust is easy to lose and difficult to regain. Information security as an industry has to understand this truth better than users, or we will fail them. If we aren’t holding ourselves accountable, slippage will occur. So I’m going to be staunch on this one.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh