Introduction

This week a Polish bank was breached through its online banking interface. According to the reports the attacker stole 250.000 USD and now uses the personal information of 80.000 customers to blackmail the bank. Allegedly the attacker exploited a remote code execution vulnerability in the online banking application to achieve all this.

We at Silent Signal performed penetration tests on numerous online banking applications, and can say that while these systems are far from flawless, RCE vulnerabilities are fairly rare. Accordingly, the majority of the in-the-wild incidents can be traced back to the client side, to compromised browsers or naive users.

But from time to time we find problems that could easily lead to incidents similar to the aforementioned Polish banks. In this case-study we’re describing a remote code execution vulnerability we discovered in an online banking application. The vulnerability is now fixed, the affected institution was not based in Poland (or our home country, Hungary).

The bug

The online bank testing account had access to an interface where users could upload various files (pictures, HTML files, Office documents, PDFs etc.). The upload interface checked the MIME type of the uploaded documents only (from the Content-Type header), but not the extension. The Content-Type header is user controlled, so uploading a public ASPX shell was an obvious way to go; but after the upload completed I got an error message that the uploaded file was not found and the message revealed the full path of the missing file on the servers filesystem. I was a bit confused because I could not reproduce this error with any other files I tried to upload. I thought it was possible that an antivirus was in place that removes the malicious document before the application could’ve handled it.

I uploaded a simple text file with the EICAR antivirus test string with .docx extension(so I could make sure that the extension wasn’t the problem) that verified this theory. The antivirus deleted the file before the application could parse it that resulted in an error message revealing the full path:

This directory was reachable from the web and the prefix of the file name was based on the current “tick count” of the system. The biggest problem was that the application removed the uploaded files after a short period of time because this was only a temporary directory. I could also only leak the names of deleted files but not the ones that remained on the system for a longer time. So exploitation required a bit more effort.

The Exploit

Before going into the details of the exploit, let’s see what “primitives” I had to work with:

- I can upload a web shell (antivirus evasion is way too easy…)

- I can leak the tick count by uploading an EICAR signature

- I can access my web shell if I’m fast enough and know the tick count of the server at the moment the shell was uploaded

Unfortunately I can’t do these three things at the same time, so this is a kind of a race condition situation. According to the documentation “a single tick represents one hundred nanoseconds or one ten-millionth of a second” so guessing the tick count on a remote system through the Internet seems like a really though job. Luckily, I don’t always trust the documentation ;)

I built a simple test application that models the primitives described and implemented a simple time synchronization algorithm that I used before to predict time on remote servers with seconds precission. The algorithm works basically by making guesses and adjusting them based on the differentials to the actual reported server times.

While this algorithm wasn’t effective on the 100ns scale, the results were really interesting! I could observe that:

- Parallel requests result in identical tick counts with high probability

- The lower bits of the tick counts tend to represent the same few values

The reason for this is probably that the server processes are not truly parallel, just the OS scheduler makes you believe they are and that the resolution of the tick counter is imperfect. I also found out, that since the filenames are only dependent on the time my requests arrive to the application, the delays of the responses introduce avoidable uncertainty.

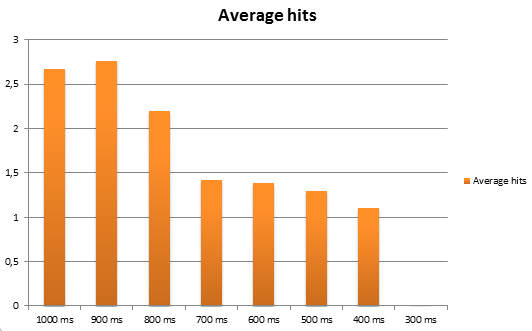

My final solution is based on grequests that is an awesome asynchronous HTTP library for Python. This allows me to issue requests very fast without having to wait for the answers in between. I’m using two parallel threads. The first uploads a number of web shells as fast as it can, while the other issues a number of requests with the EICAR string and then tries to access the web shells at constant offsets from the retrieved tick counts. The following chart shows the average hit rates (%) as the server side delays between the creation and deletion of the uploads changes:

And although a few percent doesn’t seem high, don’t forget that I had to only be lucky once! As you can see there is a limit for exploitability (with this setup) between 300 ms and 400 ms but as we later found out the uploads were transferred to a remote host, so the lifetime of the temporary files was above this limit turning the application exploitable.

The model application and the test exploit is available on GitHub.

Conclusion

In this case-study we demonstrated how a low impact information leak and a (seemingly) low exploitability file upload bug could be chained together to an attack that can result in significant financial and reputation loss.

For application developers we have the following advises:

- If you’re in doubt, use cryptographicaly secure random number generators.

- Never assume that your software will be deployed to an environment similar to your test machine. A conflicting component (like the antivirus in this case) can and will cause unexpected behavior.

- File uploads are always fragile parts of web applications, OWASP has some good guidelines about securely handling them.

And for those who are responsible for online banks or similar systems here are some thought-provoking questions:

- Do your development teams follow a security focused development methodology? Because a good methodology is the base of a quality product.

- Do you perform regular, technical security tests on your financial applications? Because people make mistakes.

- Do you fix the discovered vulnerabilities on your production systems in reasonable time? Because tests worth nothing if it takes forever to fix the findings.

- Do you have an incident response plan? Because despite all effort, incidents will eventually happen.

- Would you notice an incident? Because IR doesn’t get started by itself.

- Could you determine what the exploited vulnerabilities were and which users exploited (or tried to exploit) them? Because an incident is an opportunity to learn.