In this blog post, we show in detail how a known-plaintext attack on XOR encoding works, and automate it with custom tools to decrypt and extract the configuration of a Cobalt Strike beacon. If you are not interested in the theory, just in the tools, go straight to the conclusion 🙂 .

A known-plaintext attack (KPA) is a cryptanalysis method where the analyst has the plaintext and ciphertext version of a message. The goal of the attack is to reveal the encryption algorithm and key.

XOR encoding intro

Let’s first agree on a notational convention:

Decimal integers are represented like this:

65Hexadecimal integers are represented like this:

0x41Let’s take the following plaintext message as example:

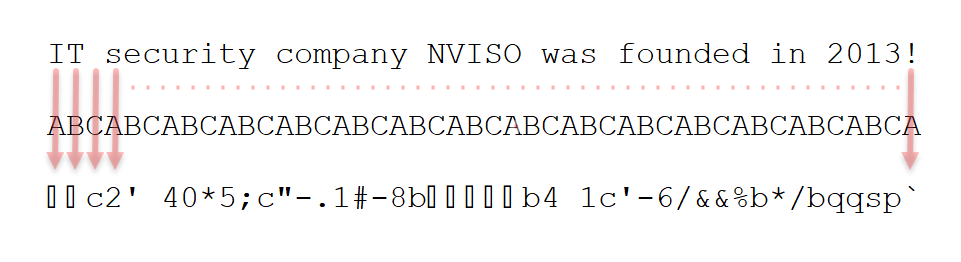

IT security company NVISO was founded in 2013!And we XOR encode this with key ABC.

Like this:

This is how this works. Character per character, we perform an 8-bit XOR operation.

- We take the first character of the plaintext message (I) and the first character of the key (A), we lookup their numeric value (according to the ASCII table): I is 0x49 and A is 0x41. Xoring 0x49 and 0x41 gives 0x08. In the ASCII table, 0x08 is a control character and thus unprintable (hence the thin rectangle in figure 1: this depicts unprintable characters).

- We take the second character of the plaintext message (T) and the second character of the key (B), we lookup their numeric value (according to the ASCII table): T is 0x54 and B is 0x42. Xoring 0x54 and 0x42 gives 0x16. In the ASCII table, 0x16 is a control character and thus unprintable.

- We take the third character of the plaintext message (space character) and the third character of the key (C), we lookup their numeric value (according to the ASCII table): is 0x20 and C is 0x43. Xoring 0x20 and 0x43 gives 0x63. In the ASCII table, 0x63 is lowercase letter c (lowercase and uppercase letters have different values: they have their 6th bit toggled).

- We take the fourth character of the plaintext message (s) and the first character of the key (A), we lookup their numeric value (according to the ASCII table): s is 0x73 and A is 0x41. Xoring 0x73 and 0x41 gives 0x32. In the ASCII table, 0x32 is digit 2. Since our XOR key (ABC) is only 3 characters long, and the plaintext is longer than 3 characters, we start repeating the key. That is why we start again with the first character of the key (A) after having used the last character of the key (C) for the previous character. We roll the key.

This goes on, until we process the 46th character:

- Character 1: we perform operation I xor A and that gives us unprintable character

- Character 2: we perform operation T xor B and that gives us unprintable character

- Character 3: we perform operation xor C and that gives us character c

- Character 4: we perform operation s xor A and that gives us character 2

- and so on ….

- Character 46: we perform operation ! xor A and that gives us character `

This example explains how we XOR a plaintext message with a key that is shorter than the plaintext message: Plaintext XOR Key -> Ciphertext.

XOR cryptanalysis

XOR encoding has an interesting property, especially if you are interested in cryptanalysis. When you XOR the plaintext message with the ciphertext, you obtain the key: Plaintext XOR Ciphertext -> Key.

That’s how XOR encoding works. Let’s now see how we can decode this, without knowing the key, neither the complete plaintext, but just with a part of the plaintext.

In the case we are dealing with here, we have the complete ciphertext and partial plaintext. Under certain circumstances (explained later), it is also possible to recover the key in such a case.

Assume that the partial plaintext we have is NVISO: we know that the string NVISO appears in the plaintext (unknown to us), but we don’t know where.

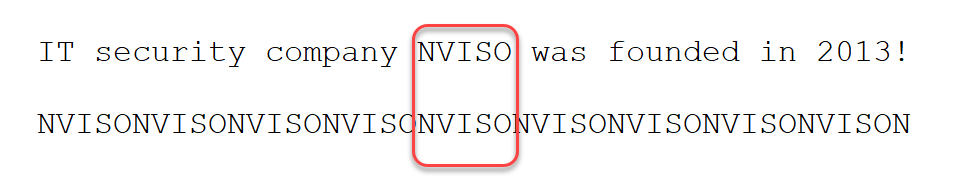

So what we will do here, is repeat the string NVISO as many times as necessary to make it as long as the ciphertext (and hence as long as the plaintext). Like this:

NVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONWhen we perform XOR operations with the ciphertext and the repeating NVISO string, we obtain this result:

What we see here, is a string of 3 characters (CAB) that starts to repeat itself (CA) and has exactly the same length as the partial plaintext: NVISO is 5 characters, CABCA is 5 characters.

This is how you can identify the key: you look for repetition, that is in total as long as the partial plaintext. Substring CABCA is the only string that satisfies this condition in the XOR result in our example. yy and bib are also repeating strings, but they are shorter than the partial plaintext (5 characters).

And this also illustrates the most important condition for a partial KPA attack on XOR encoding to succeed: the partial plaintext must be longer than the XOR key. If the partial plaintext is as long, or shorter, than the XOR key, we will not observe repetition, and thus we will not be able to identify the key.

The string that contains our XOR key is CABCA. Since we assume that we are dealing with a rolling XOR key, the key can be ABC, BCA or CAB.

Let’s expand that string that contains our XOR key, to the left and to the right, so that it is as long as the ciphertext:

And finally, use that as the key stream for the XOR operation:

And now we have recovered the complete plaintext, by knowing a part of it that is longer than the XOR key used to encode the message.

We have designed our example so, that the ciphertext and partial plaintext align, like this:

If the number of characters preceding the ciphertext of partial plaintext NVISO would not be an exact multiple of the length of plaintext NVISO (20 / 4 = 5), then ciphertext and partial plaintext would not align properly, and we would not calculate the correct key.

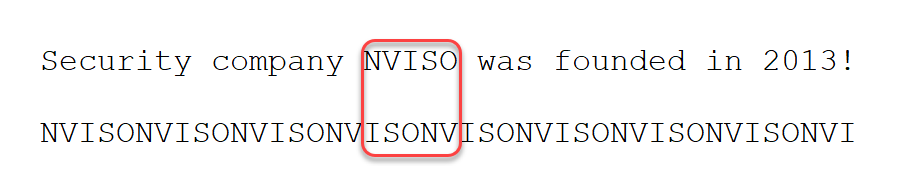

For example, like this (I removed the leading word IT):

But this can be solved by “rolling” the partial plaintext. If our partial plaintext is 5 characters long, we have to generate 5 partial plaintext streams that we have to check:

NVISO -> NVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISON

VISON -> VISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONV

ISONV -> ISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVI

SONVI -> SONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVIS

ONVIS -> ONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISONVISO

In this example, it’s the fourth stream we generated that will align, and will thus reveal the key.

A partial KPA attack on XOR encoded ciphertext with a rolling XOR key, requires a partial, known plaintext that is longer than the XOR key. The bigger the difference in length, the easier it will be to identify the XOR key.

Doing all this decoding manually is a very intensive process. That’s why we have a tool to automate this process: xor-kpa.py.

Let’s illustrate with our example.

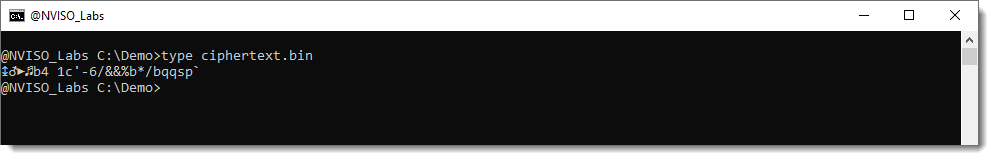

This is the encoded file (ciphertext):

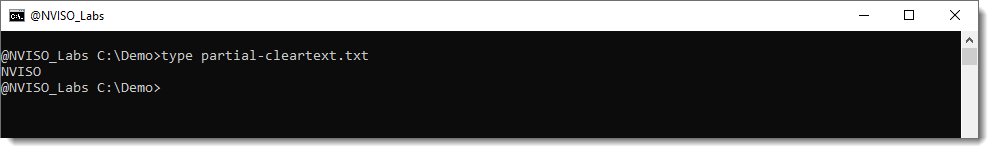

This is the file that contains the known plaintext:

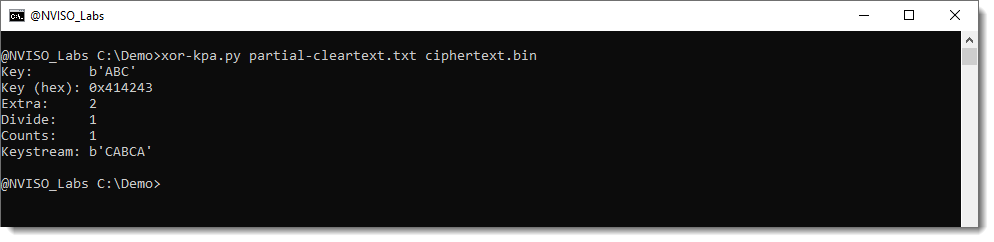

Running tool xor-kpa.py with these 2 files as input gives:

We see that the tool recovers keystream CABCA, just like we did, and infers the right key from it: ABC.

Extra tells us how many characters are repeating (thus how many extra characters the partial plaintext has compared to the XOR key). The bigger this number, the more confident we can be that the correct key was recovered.

Divide tells us how many times the complete XOR key appears in the keystream.

And counts tells us how many times this ciphertext was found (in our example, that would mean that the word NVISO appears more than once in the plaintext).

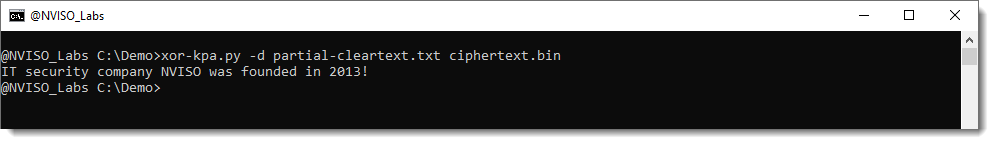

xor-kpa.py can also do the decoding for us (using option -d):

And here is an example, where the partial known plaintext is longer (was founded in 2013):

As the recovered keystream is much longer, the probability to extract the correct key is higher.

Conclusion

NVISO regularly encounters malware or artefacts that use XOR encoding with a key longer than one byte. Tool xor-kpa.py helps us to decode such files.

The tool comes with some predefined plaintexts, that appear often in samples (like “This program cannot be run in DOS mode”). We also included plaintexts for Cobalt Strike beacons.

When you run tool xor-kpa.py with the help option, you get a list of predefined plaintexts:

All the predefined plaintexts that start with cs-, are for Cobalt Strike.

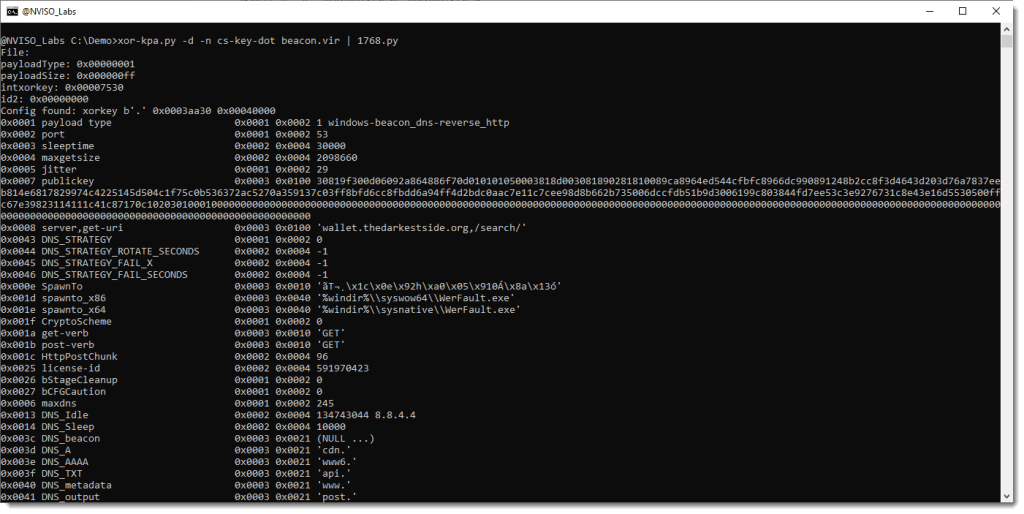

As a last example, we try to decode a file suspected to be an encoded Cobalt Strike beacon (beacon.vir). We will use cs-key-dot: this is the invariable part of the public key stored inside the beacon configuration for Cobalt Strike version 4:

Several potential keys are recovered, and the most likely key is presented at the end of the output. Potential key output is sorted by the amount of repetition in the keystream: the more repetition, the likelier the key is correct, and therefore listed lower than the keystreams with less repetition.

We can now use option -d to decode the sample with the most probable key (the last one in the list), and pipe the output to 1768.py, a tool to extract beacon configurations:

Because of the decoding with xor-kpa, 1768.py is able to extract the proper configuration.

Didier Stevens

Didier Stevens is a malware expert working for NVISO. Didier is a SANS Internet Storm Center senior handler and Microsoft MVP, and has developed numerous popular tools to assist with malware analysis.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh