2023-12-14 13:13:0 Author: research.nccgroup.com(查看原文) 阅读量:5 收藏

Max Groot and Erik Schamper

- Windows Defender (the antivirus shipped with standard installations of Windows) places malicious files into quarantine upon detection.

- Reverse engineering

mpengine.dllresulted in finding previously undocumented metadata in the Windows Defender quarantine folder that can be used for digital forensics and incident response. - Existing scripts that extract quarantined files do not process this metadata, even though it could be useful for analysis.

- Fox-IT’s open-source digital forensics and incident response framework Dissect can now recover this metadata, in addition to recovering quarantined files from the Windows Defender quarantine folder.

dissect.cstructallows us to use C-like structure definitions in Python, which enables easy continued research in other programming languages or reverse engineering in tools like IDA Pro.- Want to continue in IDA Pro? Just copy paste the structure definitions!

During incident response engagements we often encounter antivirus applications that have rightfully triggered on malicious software that was deployed by threat actors. Most commonly we encounter this for Windows Defender, the antivirus solution that is shipped by default with Microsoft Windows. Windows Defender places malicious files in quarantine upon detection, so that the end user may decide to recover the file or delete it permanently. Threat actors, when faced with the detection capabilities of Defender, either disable the antivirus in its entirety or attempt to evade its detection.

The Windows Defender quarantine folder is valuable from the perspective of digital forensics and incident response (DFIR). First of all, it can reveal information about timestamps, locations and signatures of files that were detected by Windows Defender. Especially in scenarios where the threat actor has deleted the Windows Event logs, but left the quarantine folder intact, the quarantine folder is of great forensic value. Moreover, as the entire file is quarantined (so that the end user may choose to restore it), it is possible to recover files from quarantine for further reverse engineering and analysis.

While scripts already exist to recover files from the Defender quarantine folder, the purpose of much of the contents of this folder were previously unknown. We don’t like big unknowns, so we performed further research into the previously unknown metadata to see if we could uncover additional forensic traces.

Rather than just presenting our results, we’ve structured this blog to also describe the process to how we got there. Skip to the end if you are interested in the results rather than the technical details of reverse engineering Windows Defender.

Existing Research

We started by looking into existing research into the internals of Windows Defender. The most extensive documentation we could find on the structures of Windows Defender quarantine files was Florian Bauchs’ whitepaper analyzing antivirus software quarantine files, but we also looked at several scripts on GitHub.

- In summary, whenever Defender puts a file into quarantine, it does three things:

A bunch of metadata pertaining to when, why and how the file was quarantined is held in aQuarantineEntry. ThisQuarantineEntryis RC4-encrypted and saved to disk in the/ProgramData/Microsoft/Windows Defender/Quarantine/Entriesfolder. - The contents of the malicious file is stored in a

QuarantineEntryResourceDatafile, which is also RC4-encrypted and saved to disk in the/ProgramData/Microsoft/Windows Defender/Quarantine/ResourceDatafolder. - Within the

/ProgramData/Microsoft/Windows Defender/Quarantine/Resourcefolder, aResourcefile is made. Both from previous research as well as from our own findings during reverse engineering, it appears this file contains no information that cannot be obtained from theQuarantineEntryand theQuarantineEntryResourceDatafiles. Therefore, we ignore theResourcefile for the remainder of this blog.

While previous scripts are able to recover some properties from the ResourceData and QuarantineEntry files, large segments of data were left unparsed, which gave us a hunch that additional forensic artefacts were yet to be discovered.

Windows Defender encrypts both the QuarantineEntry and the ResourceData files using a hardcoded RC4 key defined in mpengine.dll. This hardcoded key was initially published by Cuckoo and is paramount for the offline recovery of the quarantine folder.

Pivotting off of public scripts and Bauch’s whitepaper, we loaded mpengine.dll into IDA to further review how Windows Defender places a file into quarantine. Using the PDB available from the Microsoft symbol server, we get a head start with some functions and structures already defined.

Recovering metadata by investigating the QuarantineEntry file

Let us begin with the QuarantineEntry file. From this file, we would like to recover as much of the QuarantineEntry structure as possible, as this holds all kinds of valuable metadata. The QuarantineEntry file is not encrypted as one RC4 cipherstream, but consists of three chunks that are each individually encrypted using RC4.

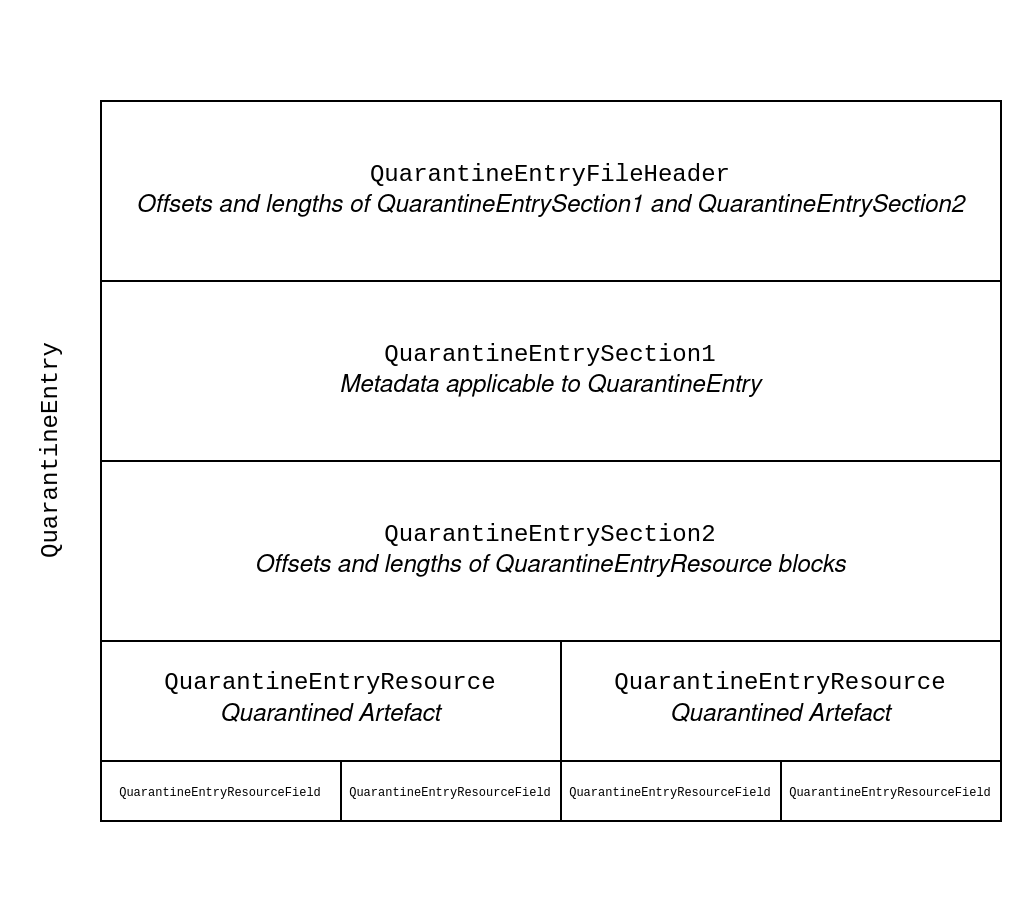

These three chunks are what we have come to call QuarantineEntryFileHeader, QuarantineEntrySection1 and QuarantineEntrySection2.

QuarantineEntryFileHeaderdescribes the size ofQuarantineEntrySection1andQuarantineEntrySection2, and contains CRC checksums for both sections.QuarantineEntrySection1contains valuable metadata that applies to allQuarantineEntryResourceinstances within thisQuarantineEntryfile, such as theDetectionNameand theScanIdassociated with the quarantine action.QuarantineEntrySection2denotes the length and offset of everyQuarantineEntryResourceinstance within thisQuarantineEntryfile so that they can be correctly parsed individually.

A QuarantineEntry has one or more QuarantineEntryResource instances associated with it. This contains additional information such as the path of the quarantined artefact, and the type of artefact that has been quarantined (e.g. regkey or file).

An overview of the different structures within QuarantineEntry is provided in Figure 1:

Figure 1: An example overview of a QuarantineEntry. In this example, two files were simultaneously quarantined by Windows Defender. Hence, there are two QuarantineEntryResource structures contained within this single QuarantineEntry.

As QuarantineEntryFileHeader is mostly a structure that describes how QuarantineEntrySection1 and QuarantineEntrySection2 should be parsed, we will first look into what those two consist of.

QuarantineEntrySection1

When reviewing mpengine.dll within IDA, the contents of both QuarantineEntrySection1 and QuarantineEntrySection2 appear to be determined in theQexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function.

The function receives an instance of the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry class. Unfortunately, the PDB file that Microsoft provides for mpengine.dll does not contain contents for this structure. Most fields could, however, be derived using the function names in the PDB that are associated with the CQexQuaEntry class:

Figure 2: Functions retrieving properties from QuarantineEntry

The Id, ScanId, ThreatId, ThreatName and Time fields are most important, as these will be written to the QuarantineEntry file.

At the start of the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function, the size of Section1 is determined.

Figure 3: Reviewing the decompiled output of CqExQuaEntry::Commit shows the size of QuarantineEntrySection1 being set to thre length of ThreatName plus 53.

This sets section1_size to a value of the length of the ThreatName variable plus 53. We can determine what these additional 53 bytes consist of by looking at what values are set in the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function for the Section1 buffer.

This took some experimentation and required trying different fields, offsets and sizes for the QuarantineEntrySection1 structure within IDA. After every change, we would review what these changes would do to the decompiled IDA view of the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function.

Some trial and error landed us the following structure definition:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| struct QuarantineEntrySection1 { | |

| CHAR Id[16]; | |

| CHAR ScanId[16]; | |

| QWORD Timestamp; | |

| QWORD ThreatId; | |

| DWORD One; | |

| CHAR DetectionName[]; | |

| }; |

While reviewing the final decompiled output (right) for the assembly code (left), we noticed a field always being set to 1:

Figure 4: A field of QuarantineEntrySection1 always being set to the value of 1.

Given that we do not know what this field is used for, we opted to name the field ‘One’ for now. Most likely, it’s a boolean value that is always true within the context of the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit commit function.

QuarantineEntrySection2

Now that we have a structure definition for the first section of a QuarantineEntry, we now move on to the second part. QuarantineEntrySection2 holds the number of QuarantineEntryResource objects confined within a QuarantineEntry, as well as the offsets into the QuarantineEntry structure where they are located.

In most scenarios, one threat gets detected at a time, and one QuarantineEntry will be associated with one QuarantineEntryResource. This is not always the case: for example, if one unpacks a ZIP folder that contains multiple malicious files, Windows Defender might place them all into quarantine. Each individual malicious file of the ZIP would then be one QuarantineEntryResource, but they are all confined within one QuarantineEntry.

QuarantineEntryResource

To be able to parse QuarantineEntryResource instances, we look into the CQexQuaResource::ToBinary function. This function receives a QuarantineEntryResource object, as well as a pointer to a buffer to which it needs to write the binary output to. If we can reverse the logic within this function, we can convert the binary output back into a parsed instance during forensic recovery.

Looking into the CQexQuaResource::ToBinary function, we see two very similar loops as to what was observed before for serializing the ThreatName of QuarantineEntrySection1. By reviewing various decrypted QuarantineEntry files, it quickly became apparent that these loops are responsible for reserving space in the output buffer for DetectionPath and DetectionType, with DetectionPath being UTF-16 encoded:

Figure 5: Reservation of space for DetectionPath and DetectionType at the beginning of CQexQuaResource::ToBinary

Fields

When reviewing the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function, we observed an interesting loop that (after investigating function calls and renaming variables) explains the data that is stored between the DetectionType and DetectionPath:

Figure 6: Alignment logic for serializing Fields

It appears QuarantineEntryResource structures have one or more QuarantineResourceField instances associated with them, with the number of fields associated with a QuarantineEntryResource being stored in a single byte in between the DetectionPath and DetectionType. When saving the QuarantineEntry to disk, fields have an alignment of 4 bytes. We could not find mentions of QuarantineEntryResourceField structures in prior Windows Defender research, even though they can hold valuable information.

The CQExQuaResource class has several different implementations of AddField, accepting different kinds of parameters. Reviewing these functions showed that fields have an Identifier, Type, and a buffer Data with a size of Size, resulting in a simple TLV-like format:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| struct QuarantineEntryResourceField { | |

| WORD Size; | |

| WORD Identifier:12; | |

| FIELD_TYPE Type:4; | |

| CHAR Data[Size]; | |

| }; |

To understand what kinds of types and identifiers are possible, we delve further into the different versions of the AddField functions, which all accept a different data type:

Figure 7: Finding different field types based on different implementations of the CqExQuaResource::AddField function

Visiting these functions, we reviewed the Type and Size variables to understand the different possible types of fields that can be set for QuarantineResource instances. This yields the following FIELD_TYPE enum:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| enum FIELD_TYPE : WORD { | |

| STRING = 0x1, | |

| WSTRING = 0x2, | |

| DWORD = 0x3, | |

| RESOURCE_DATA = 0x4, | |

| BYTES = 0x5, | |

| QWORD = 0x6, | |

| }; |

As the AddField functions are part of a virtual function table (vtable) of the CQexQuaResource class, we cannot trivially find all places where the AddField function is called, as they are not directly called (which would yield an xref in IDA). Therefore, we have not exhausted all code paths leading to a call of AddField to identify all possible Identifier values and how they are used. Our research yielded the following field identifiers as the most commonly observed, and of the most forensic value:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| enum FIELD_IDENTIFIER : WORD { | |

| CQuaResDataID_File = 0x02, | |

| CQuaResDataID_Registry = 0x03, | |

| Flags = 0x0A, | |

| PhysicalPath = 0x0C, | |

| DetectionContext = 0x0D, | |

| Unknown = 0x0E, | |

| CreationTime = 0x0F, | |

| LastAccessTime = 0x10, | |

| LastWriteTime = 0x11, | |

| }; |

Especially CreationTime, LastAccessTime and LastWriteTime can provide crucial data points during an investigation.

Revisiting the QuarantineEntrySection2 and QuarantineEntryResource structures

Now that we have an understanding of how fields work and how they are stored within the QuarantineEntryResource, we can derive the following structure for it:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

Revisiting the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function, we can now understand how this function determines at which offset every QuarantineEntryResource is located within QuarantineEntry. Using these offsets, we will later be able to parse individual QuarantineEntryResource instances. Thus, the QuarantineEntrySection2 structure is fairly straightforward:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

The last step for recovery of QuarantineEntry: the QuarantineEntryFileHeader

Now that we have a proper understanding of the QuarantineEntry, we want to know how it ends up written to disk in encrypted form, so that we can properly parse the file upon forensic recovery. By inspecting the QexQuarantine::CQexQuaEntry::Commit function further, we can find how this ends up passing QuarantineSection1 and QuarantineSection2 to a function named CUserDatabase::Add.

We noted earlier that the QuarantineEntry contains three RC4-encrypted chunks. The first chunk of the file is created in the CUserDatabase::Add function, and is the QuarantineEntryHeader. The second chunk is QuarantineEntrySection1. The third chunk starts with QuarantineEntrySection2, followed by all QuarantineEntryResource structures and their 4-byte aligned QuarantineEntryResourceField structures.

We knew from Bauch’s work that the QuarantineEntryFileHeader has a static size of 60 bytes, and contains the size of QuarantineEntrySection1 and QuarantineEntrySection2. Thus, we need to decrypt the QuarantineEntryFileHeader first.

Based on Bauch’s work, we started with the following structure for QuarantineEntryFileHeader:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| struct QuarantineEntryHeader { | |

| char magic[16]; | |

| char unknown1[24]; | |

| uint32_t section1_size; | |

| uint32_t section2_size; | |

| char unknown[12]; | |

| }; |

That leaves quite some bytes unknown though, so we went back to trusty IDA. Inspecting the CUserDatabase:Add function helps us further understand the QuarantineEntryHeader structure. For example, we can see the hardcoded magic header and footer:

Figure 8: Magic header and footer being set for the QuarantineEntryHeader

A CRC checksum calculation can be seen for both the buffer of QuarantineEntrySection1 and QuarantineSection2:

Figure 9: CRC Checksum logic within CUserDatabase::Add

These checksums can be used upon recovery to verify the validity of the file. The CUserDatabase:Add function then writes the three chunks in RC4-encrypted form to the QuarantineEntry file buffer.

Based on these findings of the Magic header and footer and the CRC checksums, we can revise the structure definition for the QuarantineEntryFileHeader:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| struct QuarantineEntryFileHeader { | |

| CHAR MagicHeader[4]; | |

| CHAR Unknown[4]; | |

| CHAR _Padding[32]; | |

| DWORD Section1Size; | |

| DWORD Section2Size; | |

| DWORD Section1CRC; | |

| DWORD Section2CRC; | |

| CHAR MagicFooter[4]; | |

| }; |

This was the last piece to be able to parse QuarantineEntry structures from their on-disk form. However, we do not want just the metadata: we want to recover the quarantined files as well.

Recovering files by investigating QuarantineEntryResourceData

We can now correctly parse QuarantineEntry files, so it is time to turn our attention to the QuarantineEntryResourceData file. This file contains the RC4-encrypted contents of the file that has been placed into quarantine.

Step one: eyeball hexdumps

Let’s start by letting Windows Defender quarantine a Mimikatz executable and reviewing its output files in the quarantine folder. One would think that merely RC4 decrypting the QuarantineEntryResourceData file would result in the contents of the original file. However, a quick hexdump of a decrypted QuarantineEntryResourceData file shows us that there is more information contained within:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| max@dissect $ hexdump -C mimikatz_resourcedata_rc4_decrypted.bin | head -n 20 | |

| 00000000 03 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 a4 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |…………….| | |

| 00000010 00 00 00 00 01 00 04 80 14 00 00 00 30 00 00 00 |…………0…| | |

| 00000020 00 00 00 00 4c 00 00 00 01 05 00 00 00 00 00 05 |….L………..| | |

| 00000030 15 00 00 00 a4 14 d2 9b 1a 02 a7 4f 07 f6 37 b4 |………..O..7.| | |

| 00000040 e8 03 00 00 01 05 00 00 00 00 00 05 15 00 00 00 |…………….| | |

| 00000050 a4 14 d2 9b 1a 02 a7 4f 07 f6 37 b4 01 02 00 00 |…….O..7…..| | |

| 00000060 02 00 58 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 14 00 ff 01 1f 00 |..X………….| | |

| 00000070 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 05 12 00 00 00 00 00 18 00 |…………….| | |

| 00000080 ff 01 1f 00 01 02 00 00 00 00 00 05 20 00 00 00 |………… …| | |

| 00000090 20 02 00 00 00 00 24 00 ff 01 1f 00 01 05 00 00 | …..$………| | |

| 000000a0 00 00 00 05 15 00 00 00 a4 14 d2 9b 1a 02 a7 4f |……………O| | |

| 000000b0 07 f6 37 b4 e8 03 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |..7………….| | |

| 000000c0 00 ae 14 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 4d 5a 90 00 |…………MZ..| | |

| 000000d0 03 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 ff ff 00 00 b8 00 00 00 |…………….| | |

| 000000e0 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |….@………..| | |

| 000000f0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |…………….| | |

| 00000100 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 20 01 00 00 0e 1f ba 0e |…….. …….| | |

| 00000110 00 b4 09 cd 21 b8 01 4c cd 21 54 68 69 73 20 70 |….!..L.!This p| | |

| 00000120 72 6f 67 72 61 6d 20 63 61 6e 6e 6f 74 20 62 65 |rogram cannot be| | |

| 00000130 20 72 75 6e 20 69 6e 20 44 4f 53 20 6d 6f 64 65 | run in DOS mode| |

As visible in the hexdump, the MZ value (which is located at the beginning of the buffer of the Mimikatz executable) only starts at offset 0xCC. This gives reason to believe there is potentially valuable information preceding it.

There is also additional information at the end of the ResourceData file:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| max@dissect $ hexdump -C mimikatz_resourcedata_rc4_decrypted.bin | tail -n 10 | |

| 0014aed0 00 00 00 00 52 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 2c 00 00 00 |….R…….,…| | |

| 0014aee0 3a 00 5a 00 6f 00 6e 00 65 00 2e 00 49 00 64 00 |:.Z.o.n.e…I.d.| | |

| 0014aef0 65 00 6e 00 74 00 69 00 66 00 69 00 65 00 72 00 |e.n.t.i.f.i.e.r.| | |

| 0014af00 3a 00 24 00 44 00 41 00 54 00 41 00 5b 5a 6f 6e |:.$.D.A.T.A.[Zon| | |

| 0014af10 65 54 72 61 6e 73 66 65 72 5d 0d 0a 5a 6f 6e 65 |eTransfer]..Zone| | |

| 0014af20 49 64 3d 33 0d 0a 52 65 66 65 72 72 65 72 55 72 |Id=3..ReferrerUr| | |

| 0014af30 6c 3d 43 3a 5c 55 73 65 72 73 5c 75 73 65 72 5c |l=C:\Users\user\| | |

| 0014af40 44 6f 77 6e 6c 6f 61 64 73 5c 6d 69 6d 69 6b 61 |Downloads\mimika| | |

| 0014af50 74 7a 5f 74 72 75 6e 6b 2e 7a 69 70 0d 0a |tz_trunk.zip..| |

At the end of the hexdump, we see an additional buffer, which some may recognize as the “Zone Identifier”, or the “Mark of the Web”. As this Zone Identifier may tell you something about where a file originally came from, it is valuable for forensic investigations.

Step two: open IDA

To understand where these additional buffers come from and how we can parse them, we again dive into the bowels of mpengine.dll. If we review the QuarantineFile function, we see that it receives a QuarantineEntryResource and QuarantineEntry as parameters. When following the code path, we see that the BackupRead function is called to write to a buffer of which we know that it will later be RC4-encrypted by Defender and written to the quarantine folder:

Figure 10: BackupRead being called withi nthe QuarantineFile function.

Step three: RTFM

A glance at the documentation of BackupRead reveals that this function returns a buffer seperated by Win32 stream IDs. The streams stored by BackupRead contain all data streams as well as security data about the owner and permissions of a file. On NTFS file systems, a file can have multiple data attributes or streams: the “main” unnamed data stream and optionally other named data streams, often referred to as “alternate data streams”. For example, the Zone Identifier is stored in a seperate Zone.Identifier data stream of a file. It makes sense that a function intended for backing up data preserves these alternate data streams as well.

The fact that BackupRead preserves these streams is also good news for forensic analysis. First of all, malicious payloads can be hidden in alternate data streams. Moreover, alternate datastreams such as the Zone Identifier and the security data can help to understand where a file has come from and what it contains. We just need to recover the streams as they have been saved by BackupRead!

Diving into IDA is not necessary, as the documentation tells us all that we need. For each data stream, the BackupRead function writes a WIN32_STREAM_ID to disk, which denotes (among other things) the size of the stream. Afterwards, it writes the data of the stream to the destination file and continues to the next stream. The WIN32_STREAM_ID structure definition is documented on the Microsoft Learn website:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| typedef struct _WIN32_STREAM_ID { | |

| STREAM_ID StreamId; | |

| STREAM_ATTRIBUTES StreamAttributes; | |

| QWORD Size; | |

| DWORD StreamNameSize; | |

| WCHAR StreamName[StreamNameSize / 2]; | |

| } WIN32_STREAM_ID; |

Who slipped this by the code review?

While reversing parts of mpengine.dll, we came across an interesting looking call in the HandleThreatDetection function. We appreciate that threats must be dealt with swiftly and with utmost discipline, but could not help but laugh at the curious choice of words when it came to naming this particular function.

Figure 11: A function call to SendThreatToCamp, a ‘call’ to action that seems pretty harsh.

We now have all structure definitions that we need to recover all metadata and quarantined files from the quarantine folder. There is only one step left: writing an implementation.

During incident response, we do not want to rely on scripts scattered across home directories and git repositories. This is why we integrate our research into Dissect.

We can leave all the boring stuff of parsing disks, volumes and evidence containers to Dissect, and write our implementation as a plugin to the framework. Thus, the only thing we need to do is parse the artefacts and feed the results back into the framework.

The dive into Windows Defender of the previous sections resulted in a number of structure definitions that we need to recover data from the Windows Defender quarantine folder. When making an implementation, we want our code to reflect these structure definitions as closely as possible, to make our code both readable and verifiable. This is where dissect.cstruct comes in. It can parse structure definitions and make them available in your Python code. This removes a lot of boilerplate code for parsing structures and greatly enhances the readability of your parser. Let’s review how easily we can parse a QuarantineEntry file using dissect.cstruct :

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| from dissect.cstruct import cstruct | |

| defender_def= """ | |

| struct QuarantineEntryFileHeader { | |

| CHAR MagicHeader[4]; | |

| CHAR Unknown[4]; | |

| CHAR _Padding[32]; | |

| DWORD Section1Size; | |

| DWORD Section2Size; | |

| DWORD Section1CRC; | |

| DWORD Section2CRC; | |

| CHAR MagicFooter[4]; | |

| }; | |

| struct QuarantineEntrySection1 { | |

| CHAR Id[16]; | |

| CHAR ScanId[16]; | |

| QWORD Timestamp; | |

| QWORD ThreatId; | |

| DWORD One; | |

| CHAR DetectionName[]; | |

| }; | |

| struct QuarantineEntrySection2 { | |

| DWORD EntryCount; | |

| DWORD EntryOffsets[EntryCount]; | |

| }; | |

| struct QuarantineEntryResource { | |

| WCHAR DetectionPath[]; | |

| WORD FieldCount; | |

| CHAR DetectionType[]; | |

| }; | |

| struct QuarantineEntryResourceField { | |

| WORD Size; | |

| WORD Identifier:12; | |

| FIELD_TYPE Type:4; | |

| CHAR Data[Size]; | |

| }; | |

| """ | |

| c_defender = cstruct() | |

| c_defender.load(defender_def) | |

| class QuarantineEntry: | |

| def __init__(self, fh: BinaryIO): | |

| # Decrypt & parse the header so that we know the section sizes | |

| self.header = c_defender.QuarantineEntryFileHeader(rc4_crypt(fh.read(60))) | |

| # Decrypt & parse Section 1. This will tell us some information about this quarantine entry. | |

| # These properties are shared for all quarantine entry resources associated with this quarantine entry. | |

| self.metadata = c_defender.QuarantineEntrySection1(rc4_crypt(fh.read(self.header.Section1Size))) | |

| # […] | |

| # The second section contains the number of quarantine entry resources contained in this quarantine entry, | |

| # as well as their offsets. After that, the individal quarantine entry resources start. | |

| resource_buf = BytesIO(rc4_crypt(fh.read(self.header.Section2Size))) |

As you can see, when the structure format is known, parsing it is trivial using dissect.cstruct. The only caveat is that the QuarantineEntryFileHeader, QuarantineEntrySection1 and QuarantineEntrySection2 structures are individually encrypted using the hardcoded RC4 key. Because only the size of QuarantineEntryFileHeader is static (60 bytes), we parse that first and use the information contained in it to decrypt the other sections.

To parse the individual fields contained within the QuarantineEntryResource, we have to do a bit more work. We cannot add the QuarantineEntryResourceField directly to the QuarantineEntryResource structure definition within dissect.cstruct, as it currently does not support the type of alignment used by Windows Defender. However, it does support the QuarantineEntryResourceField structure definition, so all we have to do is follow the alignment logic that we saw in IDA:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| # As the fields are aligned, we need to parse them individually | |

| offset = fh.tell() | |

| for _ in range(field_count): | |

| # Align | |

| offset = (offset + 3) & 0xFFFFFFFC | |

| fh.seek(offset) | |

| # Parse | |

| field = c_defender.QuarantineEntryResourceField(fh) | |

| self._add_field(field) | |

| # Move pointer | |

| offset += 4 + field.Size |

We can use dissect.cstruct‘s dumpstruct function to visualize our parsing to verify if we are correctly loading in all data:

And just like that, our parsing is done. Utilizing dissect.cstruct makes parsing structures much easier to understand and implement. This also facilitates rapid iteration: we have altered our structure definitions dozens of times during our research, which would have been pure pain without having the ability to blindly copy-paste structure definitions into our Python editor of choice.

Implementing the parser within the Dissect framework brings great advantages. We do not have to worry at all about the format in which the forensic evidence is provided. Implementing the Defender recovery as a Dissect plugin means it just works on standard forensic evidence formats such as E01 or ASDF, or against forensic packages the like of KAPE and Acquire, and even on a live virtual machine:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| max@dissect $ target-query ~/Windows10.vmx -q -f defender.quarantine | |

| <filesystem/windows/defender/quarantine/file hostname='DESKTOP-AR98HFK' domain=None ts=2022-11-22 09:37:16.536575+00:00 quarantine_id=b'\xe3\xc1\x03\x80\x00\x00\x00\x003\x12]]\x07\x9a\xd2\xc9' scan_id=b'\x88\x82\x89\xf5?\x9e J\xa5\xa8\x90\xd0\x80\x96\x80\x9b' threat_id=2147729891 detection_type='file' detection_name='HackTool:Win32/Mimikatz.D' detection_path='C:\\Users\\user\\Documents\\mimikatz.exe' creation_time=2022-11-22 09:37:00.115273+00:00 last_write_time=2022-11-22 09:37:00.240202+00:00 last_accessed_time=2022-11-22 09:37:08.081676+00:00 resource_id='9EC21BB792E253DBDC2E88B6B180C4E048847EF6'> | |

| max@dissect $ target-query ~/Windows10.vmx -f defender.recover -o /tmp/ -v | |

| 2023-02-14T07:10:20.335202Z [info] <Target /home/max/Windows10.vmx>: Saving /tmp/9EC21BB792E253DBDC2E88B6B180C4E048847EF6.security_descriptor [dissect.target.target] | |

| 2023-02-14T07:10:20.335898Z [info <Target /home/max/Windows10.vmx>: Saving /tmp/9EC21BB792E253DBDC2E88B6B180C4E048847EF6 [dissect.target.target] | |

| 2023-02-14T07:10:20.337956Z [info] <Target /home/max/Windows10.vmx>: Saving /tmp/9EC21BB792E253DBDC2E88B6B180C4E048847EF6.ZoneIdentifierDATA [dissect.target.target] |

The full implementation of Windows Defender quarantine recovery can be observed on Github.

We hope to have shown that there can be great benefits to reverse engineering the internals of Microsoft Windows to discover forensic artifacts. By reverse engineering mpengine.dll, we were able to further understand how Windows Defender places detected files into quarantine. We could then use this knowledge to discover (meta)data that was previously not fully documented or understood.

The documenting of QuarantineEntryResourceField was not available prior to this research and we hope others can use this to further investigate which fields are yet to be discovered. We have also documented how the BackupRead functionality is used by Defender to preserve the different data streams present in the NTFS file, including the Zone Identifier and Security Descriptor.

When writing our parser, using dissect.cstruct allowed us to tightly integrate our findings of reverse engineering in our parsing, enhancing the readability and verifiability of the code. This can in turn help others to pivot off of our research, just like we did when pivotting off of the research of others into the Windows Defender quarantine folder.

This research has been implemented as a plugin for the Dissect framework. This means that our parser can operate independently of the type of evidence it is being run against. This functionality has been added to dissect.target as of January 2nd 2023 and is installed with Dissect as of version 3.4.

Here are some related articles you may find interesting

Public Report – Aleo snarkVM Implementation Review

During late summer 2023, Aleo Systems Inc. engaged NCC Group’s Cryptography Services team to conduct an implementation review of several components of snarkVM, a virtual machine for zero-knowledge proofs. The snarkVM platform allows users to write and execute smart contracts in an efficient, yet privacy-preserving manner by leveraging zero-knowledge succinct…

Technical Advisory – Multiple Vulnerabilities in Nagios XI

Introduction This is the second Technical Advisory post in a series wherein I audit the security of popular Remote Monitoring and Management (RMM) tools. (First: Multiple Vulnerabilities in Faronics Insight). I was joined in this security research by Colin Brum, Principal Security Consultant at NCC Group. In this post I…

NCC Group’s 2022 & 2023 Research Report

Over the past two years, our global cybersecurity research has been characterized by unparalleled depth, diversity, and dedication to safeguarding the digital realm. The highlights of our work not only signify our commitment to pushing the boundaries of cybersecurity research but also underscore the tangible impacts and positive change we…

View articles by category

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh