Hi everyone! Today we are looking at a threat that appeared recently: a new ransomware called Sodinokibi.

Summary

- The Threat

- The Loader

- Mutex and Configuration

- Machine information recovery

- Encryption preparation inspired by GandCrab

- Ransomware attack

- C2 Registration

- Conclusion

_

The first noteworthy appearance was at the end of April (Talos Research).

Then, at the start of this month, we gathered different reports of this threat being spread in Italy (eg: JAMESWT_MHT's tweet), both via malspam and known server vulnerabilities.

Also, there was the announcement of the shutdown of the GandCrab Operation Bleeping Computer, just some days earlier.

Coincidence? We’ll see.

Our guess is that this new payload could be used as a replacement of GandCrab in the RAAS (Ransomware-as-a-service) panorama.

Therefore, in order to protect our customers effectively, we went deep into the analysis of this ransomware.

Mainly we analyzed two different samples:

- version 1.01: md5: e713658b666ff04c9863ebecb458f174

- version 1.00: md5: bf9359046c4f5c24de0a9de28bbabd14

Like every malware who deserves respect, Sodinokibi is protected by a custom packer that is different for each sample.

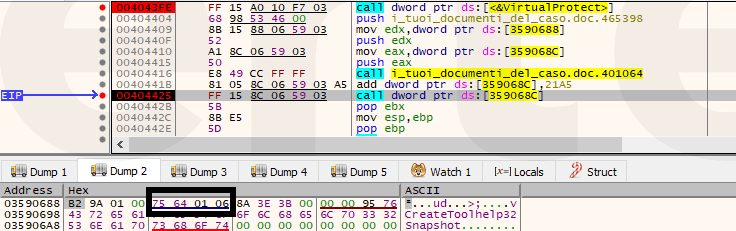

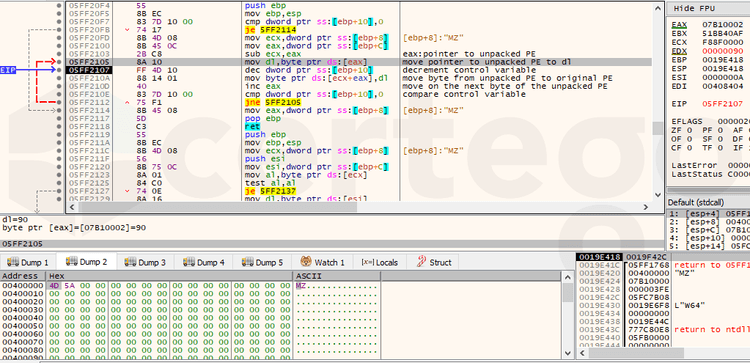

The method used by the version 1.01 sample to reconstruct the original payload is called “PE overwrite”.

To perform this technique, the malicious software must allocate a new area inside its process memory and fill it with the code that has the duty to overwrite the mapped image of the original file with the real malware payload. In this case, first the process allocates space in the Heap via LocalAlloc, then it writes the “unpacking stub” code, it signs that space as executable with VirtualProtect and finally it redirects the execution flow to the new memory space

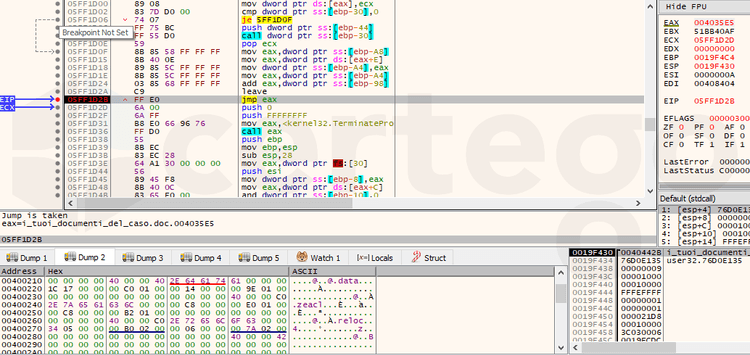

In order to slow the analysis, the loader contains a lot of junk code that will be never executed.

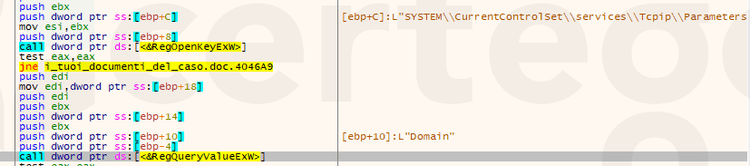

Also, in the following image, we can see that it tries to hide some important strings from the static analysis like “ kernel32.dll”. It leverages “stack strings” plus the randomization of the order of the characters.

At this point, the unpacking stub resolves dynamically the functions that he needs like VirtualAlloc. Then it performs the overwrite of the original image base with the new decrypted payload.

Finally, it transfers the execution to the OEP (Original Entry Point) of the unpacked Sodinokibi payload.

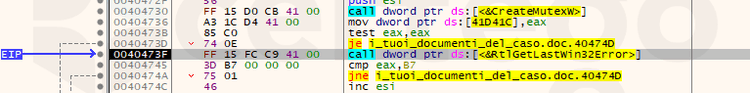

Once unpacked, the sample tries to create a mutex object. It calls CreateMutexW, then, if there was an error, with RtlGetLastWin32Error it would extract the generated error. Indeed, if the mutex already existed, the error would have been “0xB7” ("ERROR_ALREADY_EXISTS" ref docs ). In that case a function is called that terminates the process.

We found that the mutex name is different for each sample but following this pattern: “Global{UUID}”. Therefore it’s a method to detect the malware or to vaccinate the endpoint (Zeltser blog) that is reliable only for a specific sample.

Going forward, we found the configuration in an encrypted form in the section “ .zeacl” for v.1.01 or “.grrr” for v.1.00. Once extracted, we noticed that it’s a JSON file.

These are the keys found in the configuration.

- “pk” -> base64 encoded key used to encrypt files

- “pid” -> personal id of the actor

- “sub” -> another id, maybe related to the specific campaign

- “dbg” -> debug mode

- “fast” -> fast mode

- “wipe” -> enable wipe of specific directories

- “wht” -> whitelist dictionary

- “fld” -> keyword in whitelisted directories

- “fls” -> whitelisted filenames

- “ext” -> whitelisted file extensions

- “wfld” -> directories to wipe

- “prc” -> processes to kill before the encryption

- “dmn” -> domains to contact after encryption

- “net” -> check network resources

- “nbody” -> base64 encoded ransom note body

- “nname” -> ransom note file name

- “exp” -> unknown, expert mode?

- “img” -> base64 encoded message on desktop background

If you are interested in manually checking the configuration files we have extracted in the samples we have analyzed, follow this link and download the archive (password:sodinokibi): sodinokibi_config_files.zip

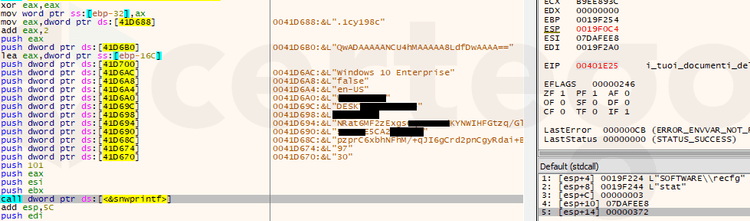

Afterwards, Sodinokibi starts to gather information about the infected machine and builds another JSON structure that stores in an encrypted form in the “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\recfg\stat” registry key.

Keys:

- “ver”: version (100 or 101)

- “pid”: previous config “pid”

- “sub”: previous config “sub”

- “pk”: previous config “pk”

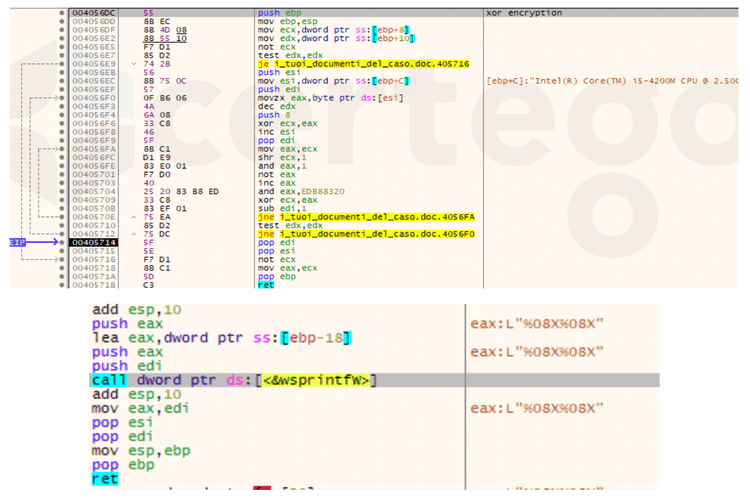

- “uid”: user ID. It’s a 8 byte hexadecimal value generated with XOR encryption. First 4 bytes are created from the processor name, while the others are created from the volume serial number extracted with a “GetVolumeInformationW” API call.

- “sk”: secondary key, base64 encoded key generated at runtime

- “unm”: username

- “net” : hostname

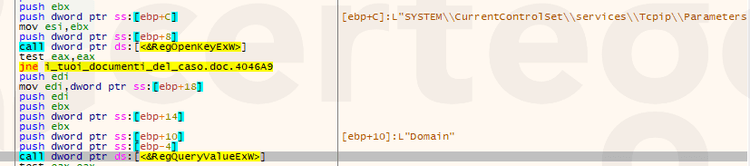

- “grp”: windows domain

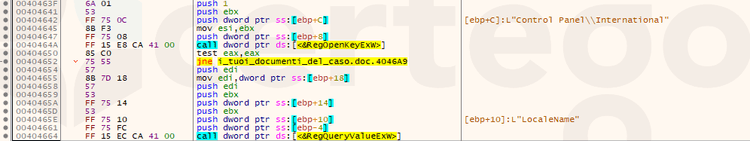

- “lng”: language

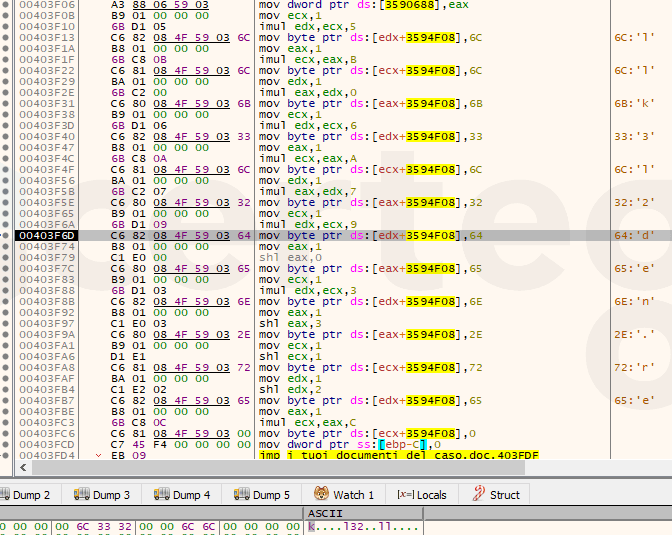

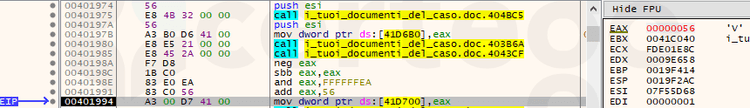

- “bro”: brother? Sodinokibi retrieves the keyboard language with GetKeyboardLayoutList. Then it implements an algorithm that gives “True” as value for this key only if the nation code ends with a byte between 0x18 and 0x2c. It’s not odd that inside this range there are the majority of the East-Europe language codes, like Russian, Cyrillic and Romanian. It’s a clear indication of the origin of the malware authors.

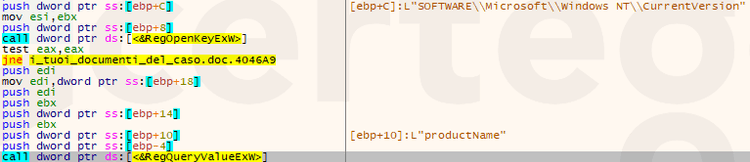

- “os”: full OS name

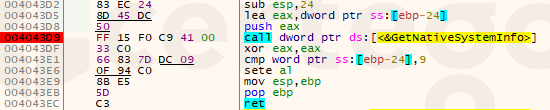

- “bit”: Sodinokibi extracts this value from “GetNativeSystemInfo” then it compares with 9 that corresponds to the x64 architecture. Further processing will generate “40” if the architecture is 64bit, “56” otherwise.

- “dsk”: base64 encoded value generated based on the drives found on the machine.

- “ext”: new in 1.01. The random extension used for encrypted files.

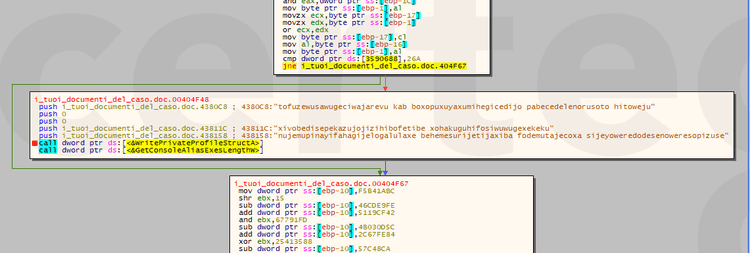

At this time, before performing the encryption, Sodinokibi replicates a behavior that is very similar to what GandCrab performs, suggesting that Sodinokibi authors learned from GandCrab ones or that they are strictly related.

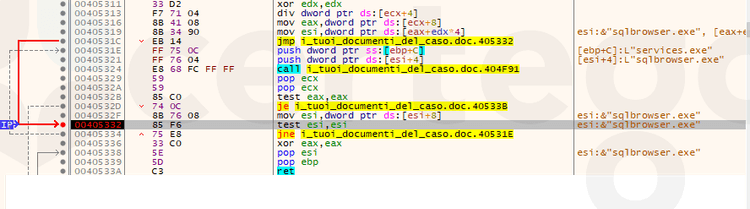

Sodinokibi extracts the running processes with the combination of CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, Process32First and Process32First and checks if they match the names in the configuration. In that case, those processes are killed. The reason is that these programs could hold write access on files and therefore they could not allow the ransomware to encrypt them.

The list of the version 1.00 contains only the “mysql.exe” process, while the list of the version 1.01 is a lot longer and almost matches the ones used by GandCrab (source: Symantec ).

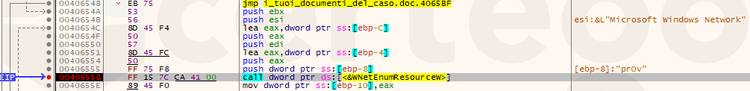

Another check done by the ransomware is for available network resources with WNetOpenEnumW e WNetEnumResourceW with the aim to find other files to encrypt.

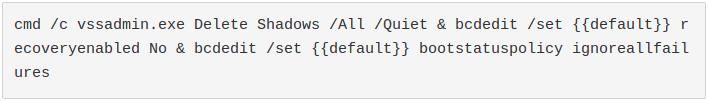

Last operation before the encryption is to find all the directories with a name that matches the configuration key “wfld” and to wipe them. In this case, the list contains only “backup”. So, for example, Sodinokibi deletes Windows Defenders updates backups.

Finally (or not?) Sodinokibi starts to iterate over the available directories with FindFirstFile and FindNextFile.

It skips files and directories that match conditions on the whitelist configuration. The others are encrypted by the ransomware that adds the random generated key as extension to the name.

In each directory the malware also write the ransom note “{ext}.readme.txt” extracted from the configuration and a lock file.

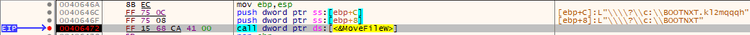

Then it creates a file with a random name “{random}.bmp” in the %TEMP% which contains the image that will be put as a background with the help of DrawTextW and FillRect functions.

Once the encryption is finished, Sodinokibi starts to iterate through a giant list of domains hardcoded in the configuration (about 1k). These domains are the same across the samples we analyzed but they are ordered differently in order to mislead the analysis.

At a first glance, these domains seem legit and most of them are correctly registered.

This is not a classic DGA but the result is almost the same because the purpose is to hide the real C&C Server used by cyber criminals.

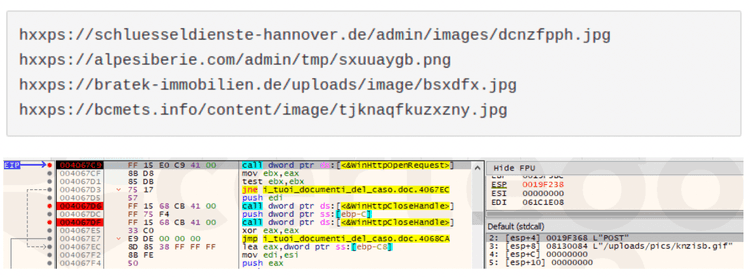

For each domain listed, Sodinokibi generates a random URI. Then it uses the winhttp.dll library functions to perform HTTPS POST requests with the created URLs.

The data sent with the POST request is an encrypted form of the JSON configuration saved on the “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\recfg\stat” registry key and described on the “Machine information recovery” section. In this way, malicious actors can collect important information of the infected machine.

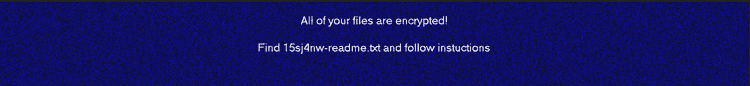

The following are examples of some of these URLs:

Looking at an analysis of this sample in a sandbox (AnyRun), we noticed that HTTPS requests where not correctly listed. The malware can avoid traffic interception by proxies like Fiddler or Mitmproxy that are used for manual or automatic analysis.

I suggest to read the following blog post where it’s further explained how these URLs are generated and why also this routine is inspired by GandCrab code: Tesorion analysis

Sodinokibi could be the heir of GandCrab. It’s still at version 1.01 so maybe it’s not mature yet but is actively developed and updated

Malicious actors have started to use Sodinokibi to generate profit, even in Italy.

It’s important to continuously monitor your own assets, both on a network and an endpoint level, to fight against these kind of threats.

Certego Threat Intelligence Team has been studying upcoming cyber threats for years in order to provide the best protection to their customers.

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\recfg\pk_key

decryptor[.]top

aplebzu47wgazapdqks6vrcv6zcnjppkbxbr6wketf56nf6aq2nmyoyd[.]onion