This article is based on research by Marcelo Rivero, Malwarebytes’ ransomware specialist, who monitors information published by ransomware gangs on their Dark Web sites. In this report, “known attacks” are those where the victim did not pay a ransom. This provides the best overall picture of ransomware activity, but the true number of attacks is far higher.

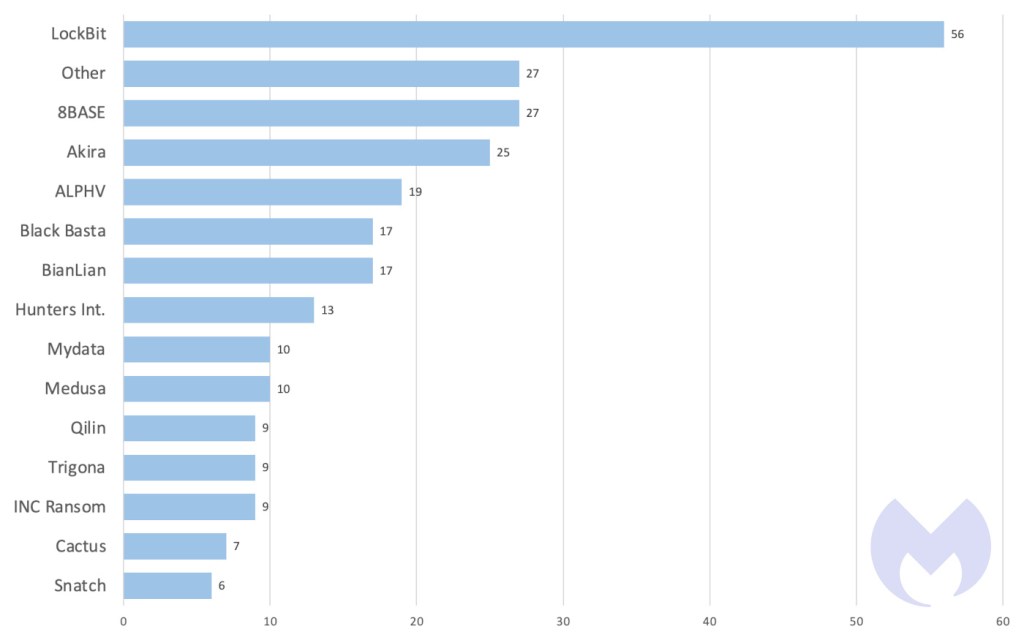

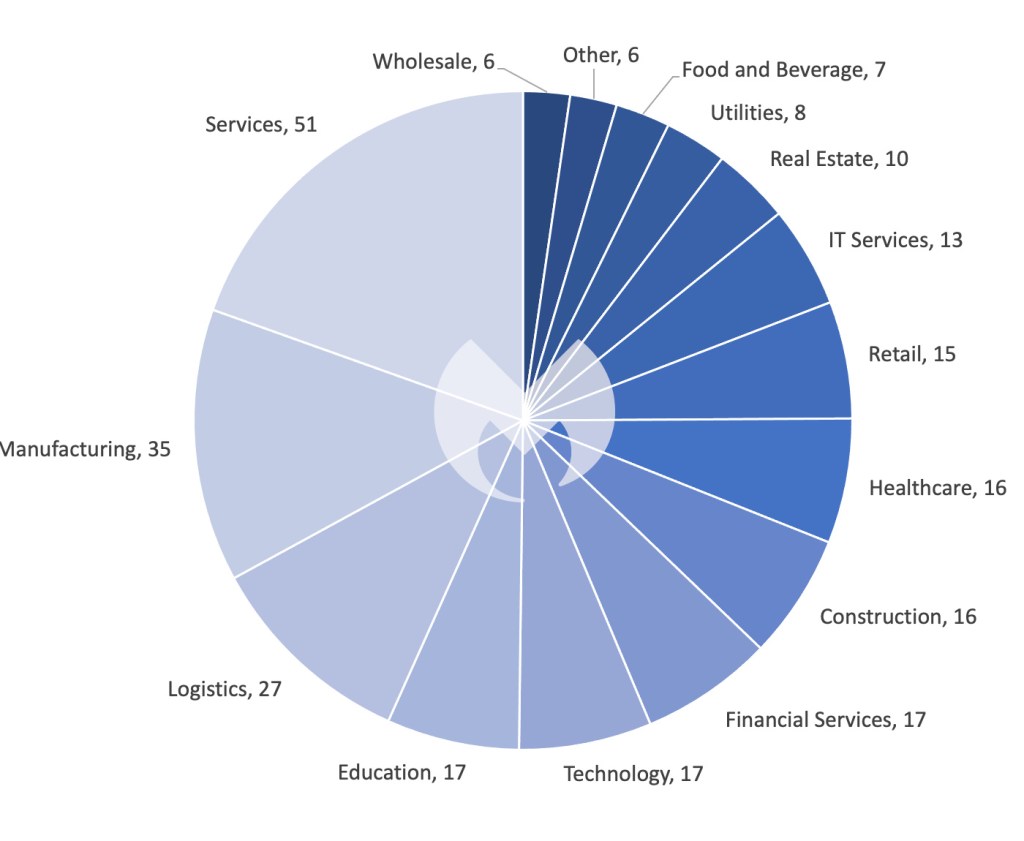

In January, we recorded a total of 261 ransomware victims, the lowest number of attacks since February 2023. This is normal, as past data reveals that historical January months tend to be one of the least active periods for ransomware gangs. But don’t let the relatively low number of attacks fool you: there was plenty of important ransomware news last month.

In January, researchers observed fake “security researchers” trying to trick ransomware victims into thinking that they can recover their stolen data. Described as “follow-on extortion” attacks, the goal of these scams is to get the victims to pay Bitcoin for supposed assistance.

The two examples we have of follow-on extortion attacks targeted victims of the Royal and Akira ransomware gangs, but it’s unclear if the fake security researchers are a part of either of those gangs. Our guess? It’s more likely that they are a fringe group simply seizing an opportunity to exploit victims already targeted by these gangs.

Let’s analyze why, using two scenarios, assuming that the follow-up extortioners really are Royal or Akira.

In scenario one, Royal or Akira steals data, prompting a ransom payment from the victim for data deletion. Then, Royal or Akira sends a splinter group to the same victim claiming Royal didn’t delete the data, offering deletion services for an additional fee. This scenario is pretty unlikely, as it undermines Royal’s credibility from the victim’s perspective, damaging the gang’s reputation.

In scenario two, Royal or Akira steals data, but the victim hasn’t paid for deletion yet. The Royal or Akira splinter group then offers to recover the data for a fee. This predicament forces the victim to choose who to trust, likely deciding that it might be more logical to rely on Royal since they have more incentive to maintain a semblance of reliability. So, it then just becomes a normal double-extortion case but with an unnecessary extra step.

In the first case, the “initial ransomware gang” has no leverage for a second round of extortion without contradicting their own claims and damaging their reputation. In the second case, the initial ransomware gang just does more work to get the same outcome, namely payment for data deletion.

Neither option presents a guaranteed connection to the original attackers.

In other January news, the UK’s National Cybersecurity Centre (NCSC) released a report suggesting that AI will boost ransomware attack volume and severity in the next two years, particularly through lowering the entry barrier for novice hackers. A simple example is an affiliate using generative AI to create more persuasive phishing emails. This could decrease affiliates’ dependence on Initial Access Brokers for accessing networks, leading to more attacks by individuals enticed by the lower initial investment.

In general, however, we should be cautious about these predictions. Incorporating AI into cybercrime—especially for automated discovery of vulnerabilities or efficient high-value data extraction, as NCSC’s report suggests—is extremely complex and costly. For major gangs like LockBit and CL0P, who manage multimillion-dollar operations, adopting these AI advancements might be more feasible, yet it is still far too early to speculate upon.

In our view, RaaS groups will maintain their current operations in the short term. AI may introduce new methods and techniques for cybercriminals, to be sure, but the core principles of ransomware gangs—based on access, leverage, and profit—will likely continue unchanged for the foreseeable future.

In other news, researchers last month witnessed Black Basta affiliates leveraging a new phishing campaign aimed at delivering a relatively new loader named PikaBot.

PikaBot, an ostensible replacement for the notorious OakBot malware, is an initial access tool that we first wrote about in mid-December—and it looks like it didn’t take ransomware gangs long to start using it. While our original post about PikaBot focused on its distribution via malicious search ads and not phishing emails, ransomware gangs are known to use both attack vectors to gain initial access.

A typical distribution chain for PikaBot, writes ThreatDown Intelligence researcher Jérôme Segura, usually starts with an email (within an already-hijacked thread) containing a link to an external website. Users are then tricked to download a zip archive containing malicious JavaScript that downloads Pikabot from an external server.

As this news marks the first time that PikaBot has been publicly connected with any ransomware operations, it’s safe to assume that the malware is actively being used by other gangs as well—or that if it’s not, it will be soon.

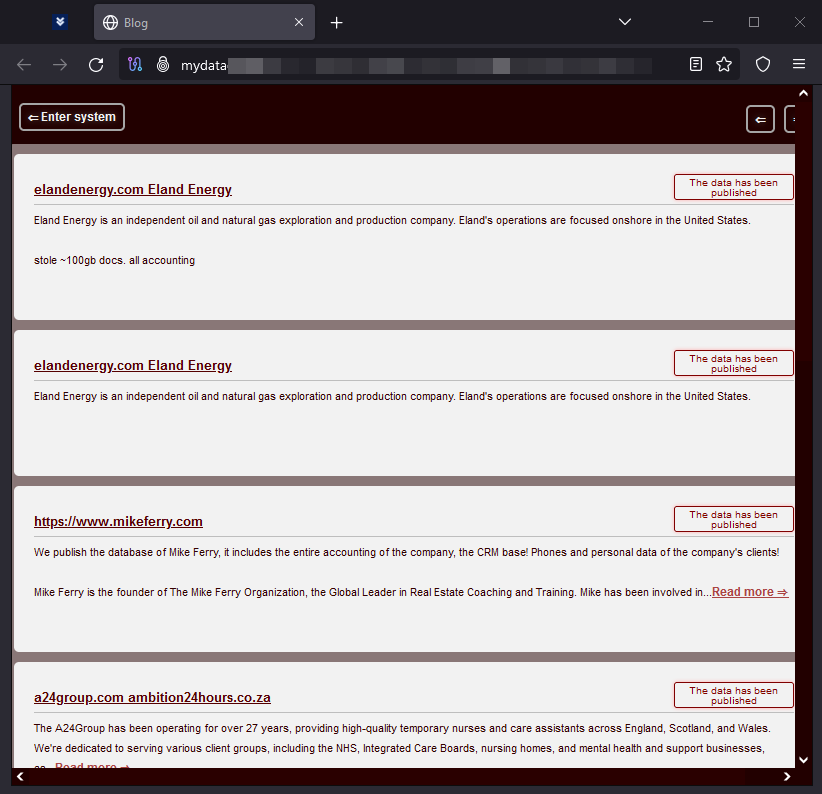

New leak site: MYDATA

Mydata is a new leak site from Alpha ransomware, a distinct group not to be confused with ALPHV ransomware. The site published the data of 10 victims in January.

MYDATA leak data

Preventing Ransomware

Fighting off ransomware gangs like the ones we report on each month requires a layered security strategy. Technology that preemptively keeps gangs out of your systems is great—but it’s not enough.

Ransomware attackers target the easiest entry points: an example chain might be that they first try phishing emails, then open RDP ports, and if those are secured, they’ll exploit unpatched vulnerabilities. Multi-layered security is about making infiltration progressively harder and detecting those who do get through.

Technologies like Endpoint Protection (EP) and Vulnerability and Patch Management (VPM) are vital first defenses, reducing breach likelihood.

The key point, though, is to assume that motivated gangs will eventually breach defenses. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) is crucial for finding and removing threats before damage occurs. And if a breach does happen—ransomware rollback tools can undo changes.

How ThreatDown Addresses Ransomware

ThreatDown bundles take a comprehensive approach to these challenges. Our integrated solutions combine EP, VPM, and EDR technologies, tailored to your organization’s specific needs. ThreatDown’s select bundles offer:

- Advanced Web Protection: Blocking phishing websites ransomware gangs use for initial access.

- RDP Shield: Securing remote access points with Brute Force Protection.

- Continuous Vulnerability Scanning and Patch Management: Identifying and patching weaknesses before ransomware gangs can exploit them.

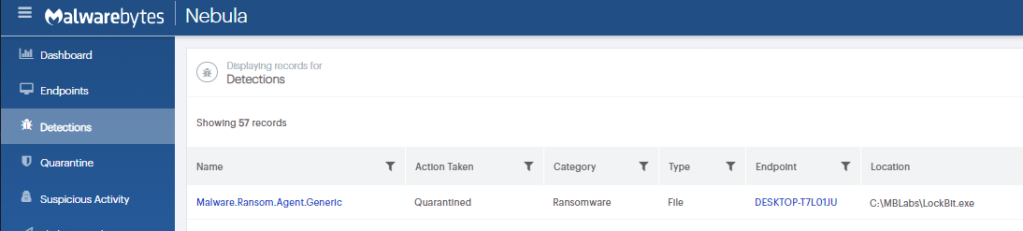

- Sophisticated EDR: Detecting and neutralizing advanced threats such as LockBit within the network.

- Ransomware Rollback: Reversing the impact of any successful attacks.

ThreatDown EDR detecting LockBit ransomware

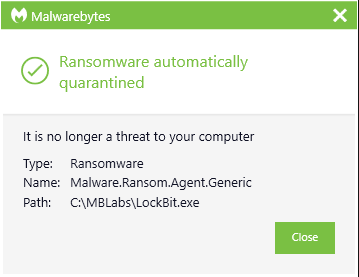

ThreatDown automatically quarantining LockBit ransomware

For resource-constrained organizations, select ThreatDown bundles offer Managed Detection and Response (MDR) services, providing expert monitoring and swift threat response to ransomware threats—without the need for large in-house cybersecurity teams.

Our business solutions remove all remnants of ransomware and prevent you from getting reinfected. Want to learn more about how we can help protect your business? Get a free trial below.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh