2024-5-23 18:0:36 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:16 收藏

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

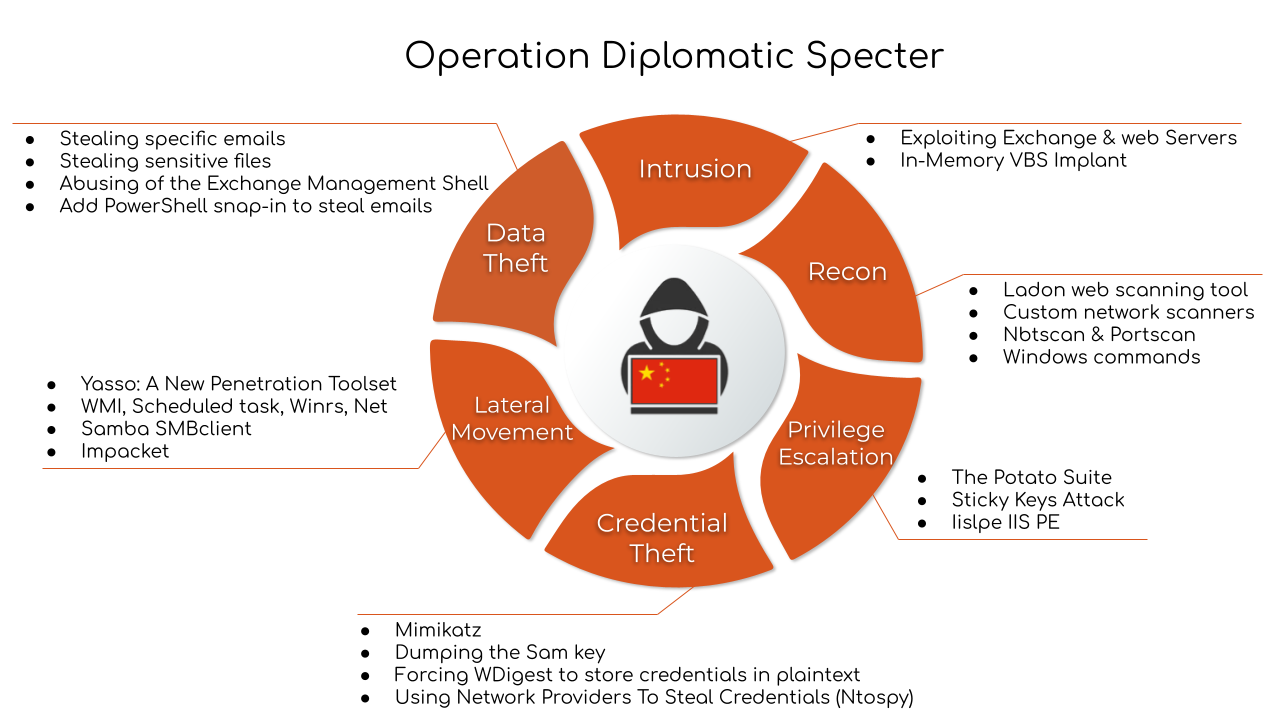

A Chinese advanced persistent threat (APT) group has been conducting an ongoing campaign, which we call Operation Diplomatic Specter. This campaign has been targeting political entities in the Middle East, Africa and Asia since at least late 2022.

An analysis of this threat actor’s activity reveals long-term espionage operations against at least seven governmental entities. The threat actor performed intelligence collection efforts at a large scale, leveraging rare email exfiltration techniques against compromised servers.

This collection effort includes attempts to obtain sensitive and classified information about the following entities, focusing on current geopolitical affairs:

- Diplomatic and economic missions

- Embassies

- Military operations

- Political meetings

- Ministries of the targeted countries

- High-ranking officials

As part of its espionage activities, the group makes use of a previously undocumented family of backdoors, including those that we have named TunnelSpecter and SweetSpecter.

The threat actor appears to closely monitor contemporary geopolitical developments, attempting to exfiltrate information daily. The threat actor’s modus operandi in cases we observed was to infiltrate targets’ mail servers and to search them for information. We observed multiple efforts to maintain persistence, including repeated attempts to adapt and regain access when the actor’s activities were disrupted. They also appear to return to the well to search for relevant information when new geopolitical events occur.

We assess with high confidence that a single threat actor orchestrates Operation Diplomatic Specter, operating on behalf of Chinese state-aligned interests. The tactics observed as part of this campaign show the extent to which Chinese state-aligned threat actors attempt to gather information about affairs beyond the Asian region, even extending into the Middle East and Africa.

It is unclear exactly how threat actors are using the intelligence collected as part of this campaign. However, the topics the threat actors searched for reveal information about many key players in these regions and their connections to China and other parts of the world. The topics they searched for provide researchers a window into the possible priorities of Chinese state-aligned threat actors.

In addition, the threat actor’s repeated use of Exchange server exploits (ProxyLogon CVE-2021-26855 and ProxyShell CVE-2021-34473) for initial access further emphasizes the importance for organizations to harden and patch sensitive internet-facing assets. This is especially true for known and prominent vulnerabilities, to reduce the attack surface and maximize protection efforts.

Organizations that safeguard sensitive information should pay particular attention to commonly exploited vulnerabilities. They should also adhere to best practices when it comes to IT hygiene, as APTs often seek to gain access through methods they know have been effective in the past.

Lastly, we are sharing our analysis to provide defenders with means to detect and protect themselves against such advanced attacks.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected against Operation Diplomatic Specter through the following:

- Network Security: Delivered through a Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW) configured with machine learning enabled and cloud-delivered security services. This includes Advanced Threat Prevention, Advanced URL Filtering, Advanced DNS Security and WildFire, a malware protection engine capable of identifying and blocking malicious samples and infrastructure.

- Security Automation: Delivered through a Cortex XSOAR or XSIAM solution capable of providing SOC analysts with a comprehensive understanding of the threat derived by stitching together data obtained from endpoints, network, cloud and identity systems.

- Anti-Exploit protection: Delivered through Cortex XSIAM and provides protection against exploitation of different vulnerabilities including ProxyShell and ProxyLogon.

- Cloud Security: Prisma Cloud Compute and WildFire integration can help detect and prevent malicious execution of the Specter backdoor within Windows-based VM, container and serverless cloud infrastructure.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | China, Backdoor |

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Operation Diplomatic Specter Motivation and Victimology

Investigating the Actor Behind Operation Diplomatic Specter

Meet the Specter Family – Cousins of Gh0st RAT

TunnelSpecter Key Features

SweetSpecter Key Features

A Gh0st RAT Variant Blasts From the Past

Connection to the Chinese Nexus

Conclusion

Protections and Mitigations

Indicators of Compromise

Additional Resources

Appendix A: Main TTPs Observed in Operation Diplomatic Specter

Appendix B: Additional Technical Details on the Backdoors

Appendix C: Additional Details on the Attribution to the Chinese Nexus

Operation Diplomatic Specter Motivation and Victimology

The threat actor behind Operation Diplomatic Specter searches for information on politicians, military operations and personnel, as well as governmental ministries, with a particular focus on foreign affairs ministries and embassies. Figure 1 shows the regions where the threat actor targets organizations in the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

Moreover, the threat actor appears to closely monitor contemporary geopolitical developments, demonstrating an intent to acquire information associated with ongoing events. The campaign has been operating since at least late 2022, with automatic exfiltration attempts occurring daily, in addition to periodic efforts involving more hands-on-keyboard attention from the threat actor.

These events encompass a wide range of subjects, including the following:

- Military operations

- Meetings

- Summits

- Conflicts

- Other pertinent aspects of current geopolitical affairs

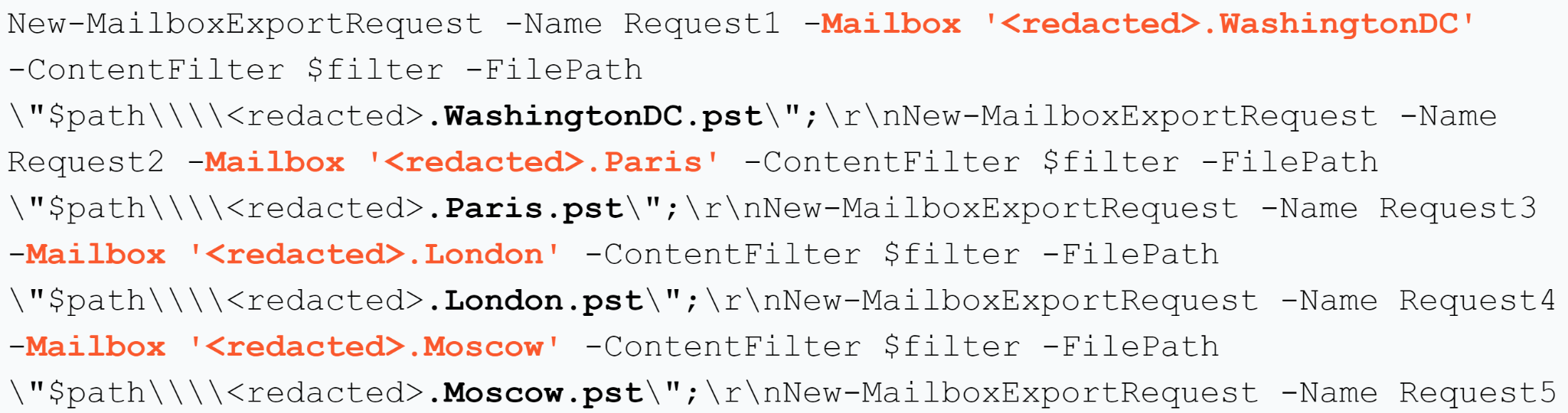

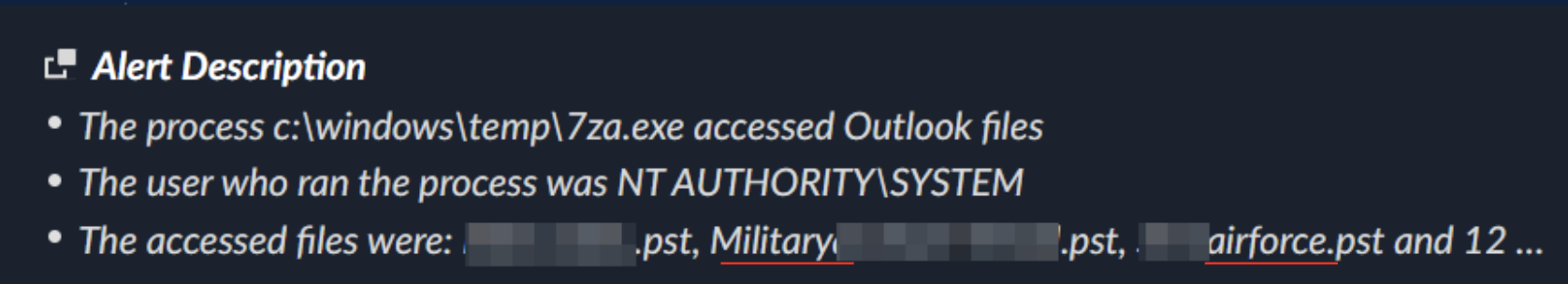

In some cases, the threat actor searched for particular keywords and exfiltrated anything they could find related to them, such as entire archived inboxes belonging to particular diplomatic missions or individuals. The threat actor also exfiltrated files related to topics they were searching for.

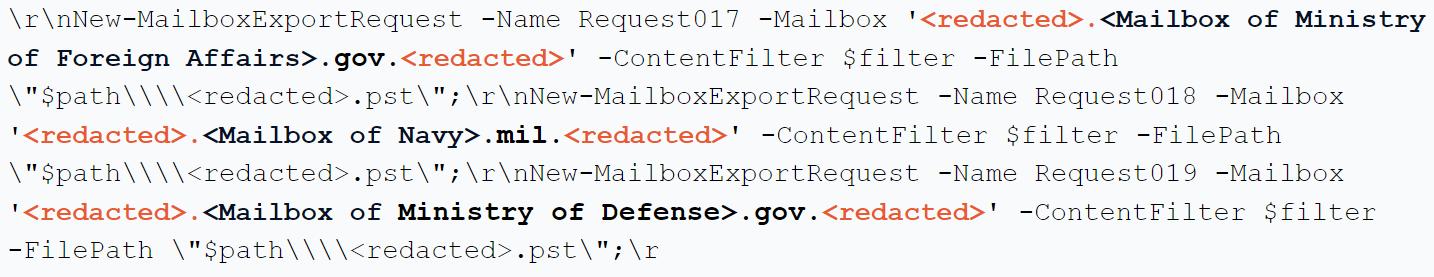

In other cases, the threat actor’s exfiltration appeared more targeted and exfiltration focused on the results of more specific searches. Searches observed related to the following topics:

- China-related geopolitical and economic information (meetings, summits, relationship with other countries, information related to President Xi)

- OPEC and energy industry

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and embassies worldwide

- Ministry of Defense

- Military (operations, drills, code words, military units and personnel)

- The relationship of the targeted countries with the Biden administration

- Local and international political figures

- Geopolitical and economical information

- Telecommunications technology used by the targeted entities

Figure 2 shows an example of the automated mailbox harvesting of one of the affected countries’ embassies and diplomatic missions.

Figures 3 and 4 show examples of threat actors targeting mailboxes of the ministry of foreign affairs, ministry of defense, as well as military organizations including the navy, air force and specific task forces of the targeted country.

Investigating the Actor Behind Operation Diplomatic Specter

Operation Diplomatic Specter is the name we’ve given to the espionage campaign described above. The details we’re sharing about this campaign are part of our ongoing investigation into an apparent Chinese state-aligned APT group.

Since late 2022, we have been tracking an activity cluster targeting governmental entities in the Middle East, Africa and Asia. In earlier stages of our tracking, we referred to the cluster as "CL-STA-0043,” indicating a cluster of activity that we suspect is associated with state-backed motivation (as described in “It’s All in the Name: How Unit 42 Defines and Tracks Threat Adversaries”).

We published on CL-STA-0043 in June 2023 in “Through the Cortex XDR Lens: Uncovering a New Activity Group Targeting Governments in the Middle East and Africa.”

In December 2023, Unit 42 published additional information related to CL-STA-0043 in “New Tool Set Found Used Against Organizations in the Middle East, Africa and the US.”

The tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) associated with the threat actor behind this cluster are relatively unique and rare. Some of these TTPs had not been reported as being used in the wild before, and some were reported used only a handful of times. For in-depth details of the TTPs observed in association with Operation Diplomatic Specter, please see Appendix A.

The threat actor demonstrated adaptability in attempting to thwart various mitigation efforts. They also sought to maintain a persistent presence in compromised environments through the use of two novel and previously undocumented malware strains – SweetSpecter and TunnelSpecter.

We will cover the key details of these backdoors in the following section, Meet the Specter Family. For a deeper dive, please see Appendix B.

After meticulously monitoring the threat actor's activities, evolution and changes over a year, we graduated the activity cluster CL-STA-0043 to a temporary actor group (TGR-STA-0043) according to Unit 42’s cluster maturation process. Essentially, the graduation indicates our confidence that a single actor is behind the activity observed, and that we’ve established “several correlation points over time and across activity clusters.”

In relation to this process, we note that the threat actor appears to be aligned with Chinese state interests and bears the hallmarks of Chinese APTs. For more details of this attribution, please read the section on Connection to the Chinese Nexus. For more in-depth details, please see Appendix C.

Meet the Specter Family – Cousins of Gh0st RAT

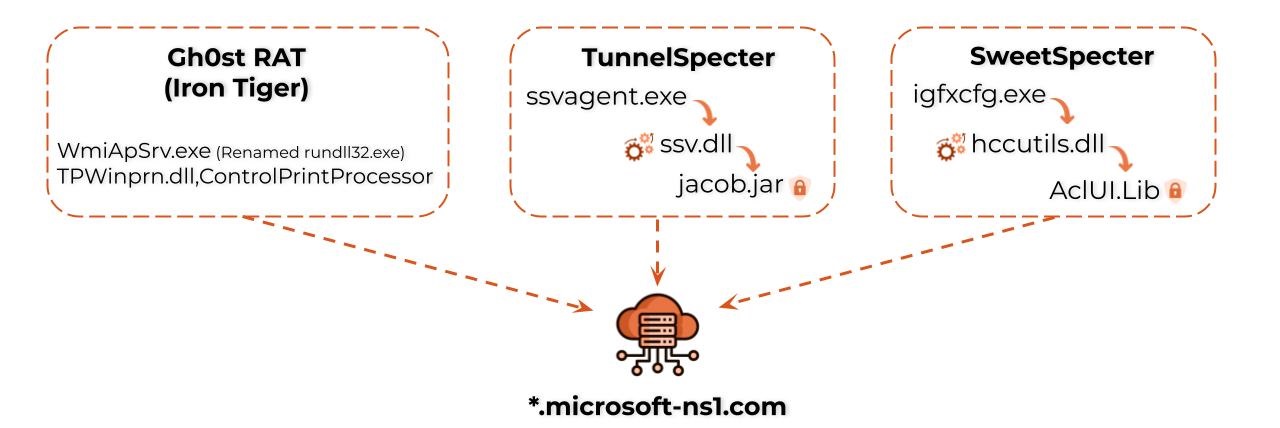

One of the TTPs that most characterizes TGR-STA-0043 (and Operation Diplomatic Specter) is the use of custom-built backdoors that were not publicly observed before. During our investigation, we uncovered a pair of unique and stealthy backdoors that we call the Specter family, including TunnelSpecter and SweetSpecter.

We named the pair the Specter family to acknowledge a similarity to Gh0st RAT (described below). TunnelSpecter’s name refers to its DNS tunneling functionality and SweetSpecter’s name references similarities to the SugarGh0st RAT specifically.

The attackers used these backdoors to maintain stealthy access to their targets’ networks. The backdoors also provided them with the ability to execute arbitrary commands, exfiltrate data, and deploy further malware and tools on the infected hosts.

According to our analysis, we believe with a high level of confidence that these two distinct backdoors borrowed small portions of code from the Gh0st RAT source code that was leaked in 2008. However, these new backdoors appear to differ from other known Gh0st RAT variants.

TunnelSpecter Key Features

- Custom tailored for a specific target, it created a rogue user that we found on that specific target

- It implemented data encryption and exfiltration over DNS tunneling for increased stealth

- It executed arbitrary commands and storage of configuration data in a rarely seen registry key

SweetSpecter Key Features

- It communicated with the C2 using encrypted zlib packets transmitted over raw TCP stream, in typical Gh0st RAT fashion

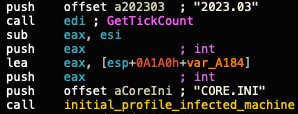

- Its compilation time was in correlation with a unique campaign ID format, using a month and year as a campaign identifier

- It used unique registry keys to store other configuration data

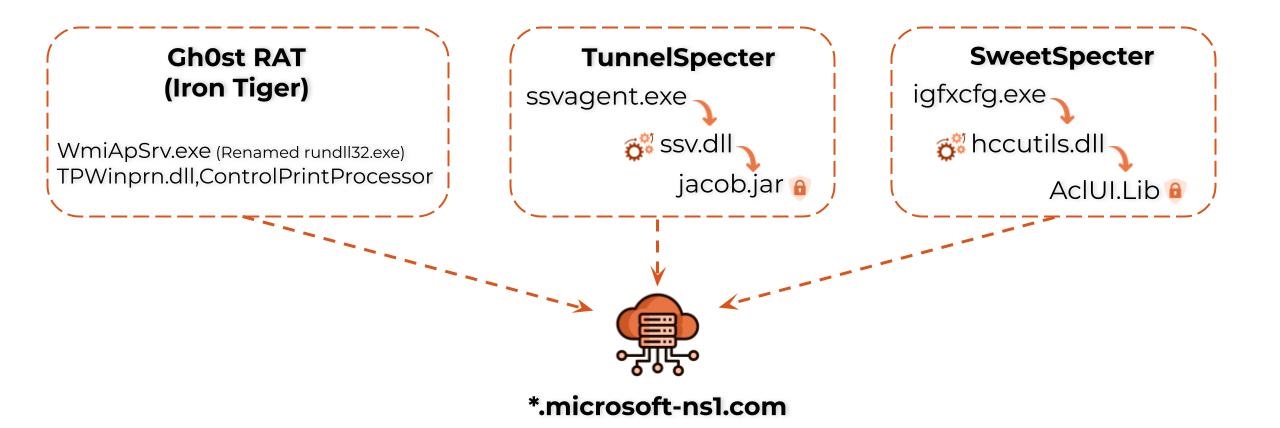

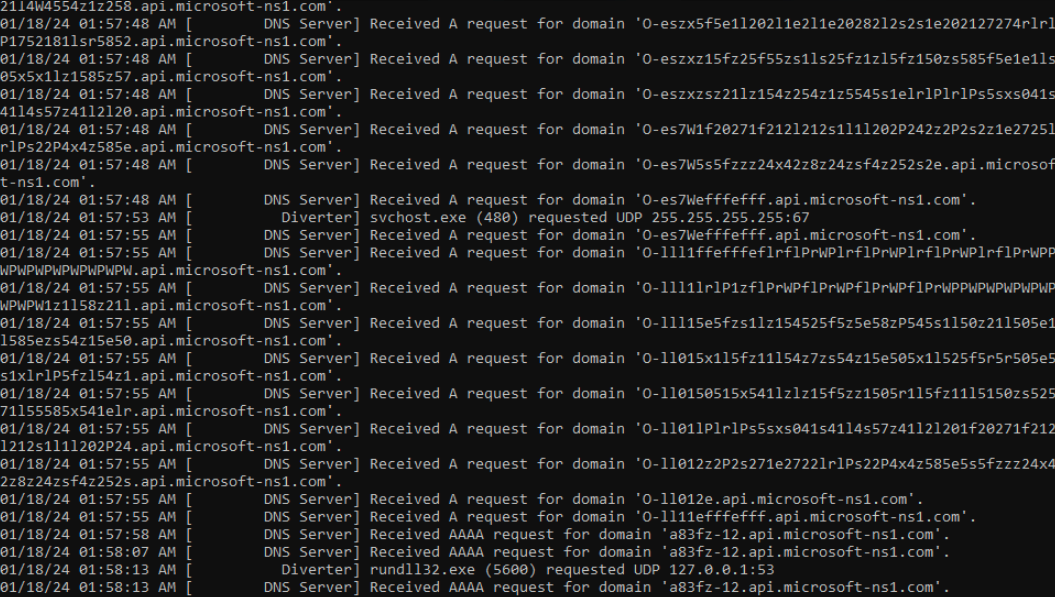

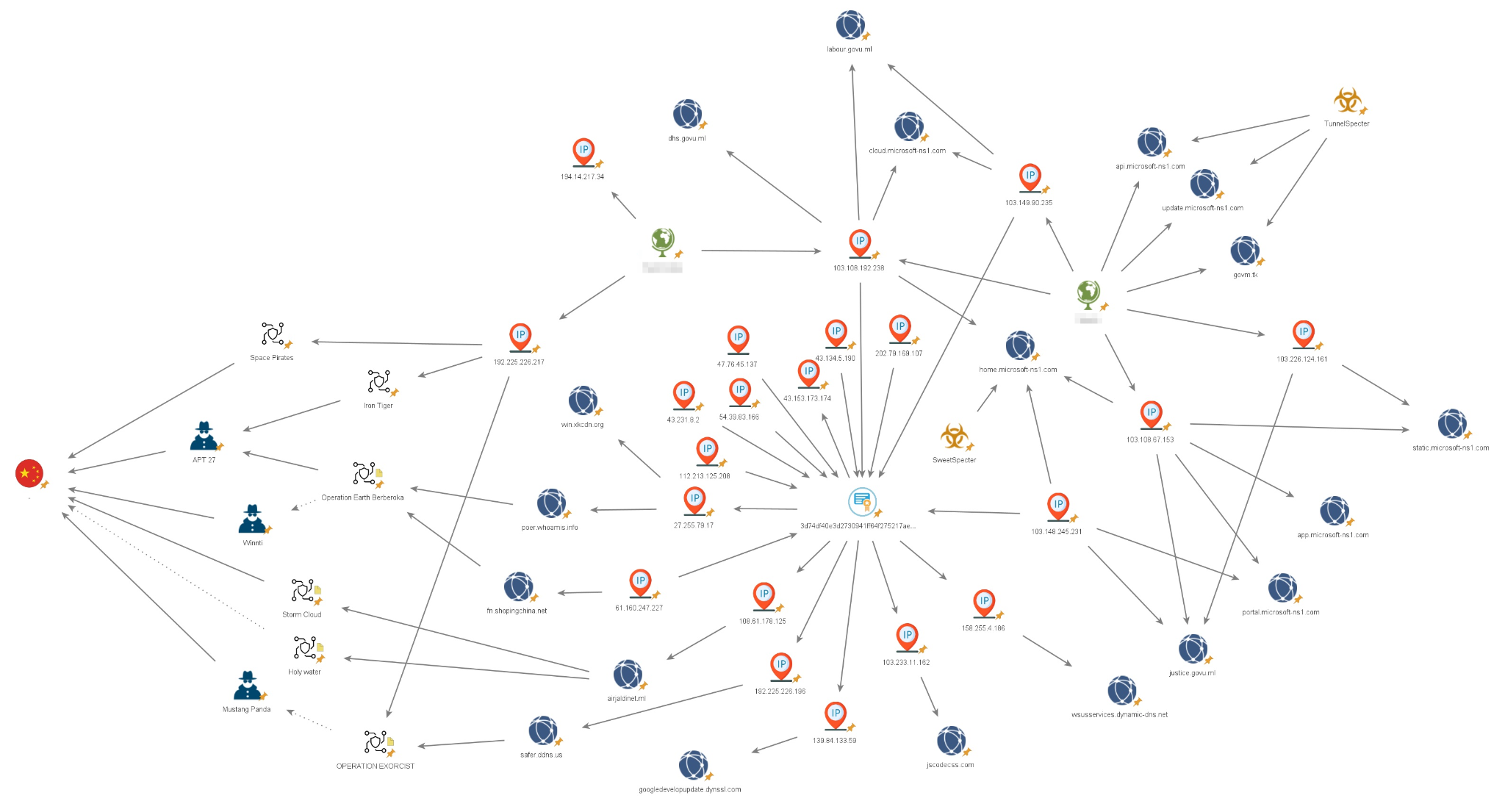

It is noteworthy that we found a sample of Gh0st RAT in the same location as the Specter backdoors, further strengthening the connection. On top of that, all of these backdoors communicated with the same embedded infrastructure – subdomains of microsoft-ns1[.]com, as shown in Figure 5.

For an in-depth analysis of TunnelSpecter and SweetSpecter, please refer to Appendix B.

A Gh0st RAT Variant Blasts From the Past

One of the types of malware used during the attacks associated with Operation Diplomatic Specter is the infamous Gh0st RAT malware family. We observed that threat actors attempted to use it to maintain a foothold in the compromised environments.

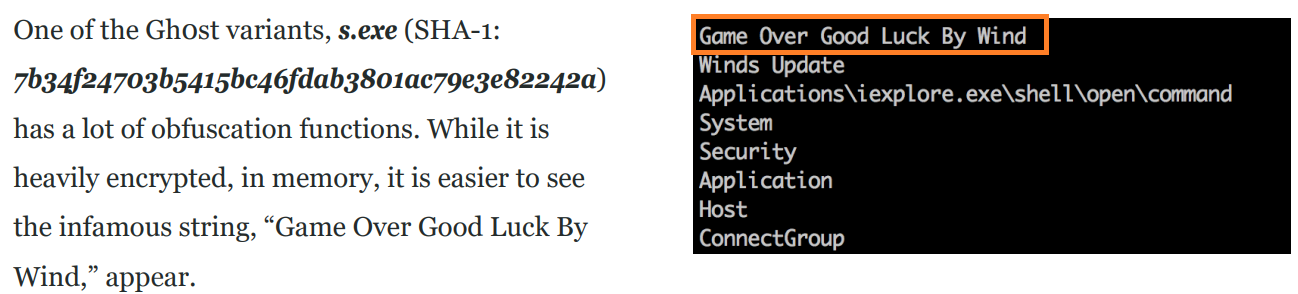

The first Gh0st RAT binary that we encountered during the attacks was a large file (approximately 280 MB) by the name Tpwinprn.dll. This file that the web shell dropped under the SysWOW64 folder was executed using a renamed rundll32.exe process.

When investigating this binary, we found that it has a notable string in memory: Game Over Good Luck By Wind. Figure 6 shows that this string was also observed in the Gh0st RAT variant used in Operation Iron Tiger [PDF] back in 2015. Iron Taurus, aka APT27, carried out this operation.

Connection to the Chinese Nexus

Our investigation revealed strong connections and overlaps that tie the group behind Operation Diplomatic Specter to the Chinese nexus of espionage-focused threat actors. These connections and overlaps, covered in greater detail in Appendix C, consist of the following facets:

- Infrastructure: The activity in Operation Diplomatic Specter originated from a shared Chinese APT operational infrastructure, exclusively used by Chinese nation-state threat actors, such as Iron Taurus (aka APT27), Starchy Taurus (aka Winnti) and Stately Taurus (aka Mustang Panda).

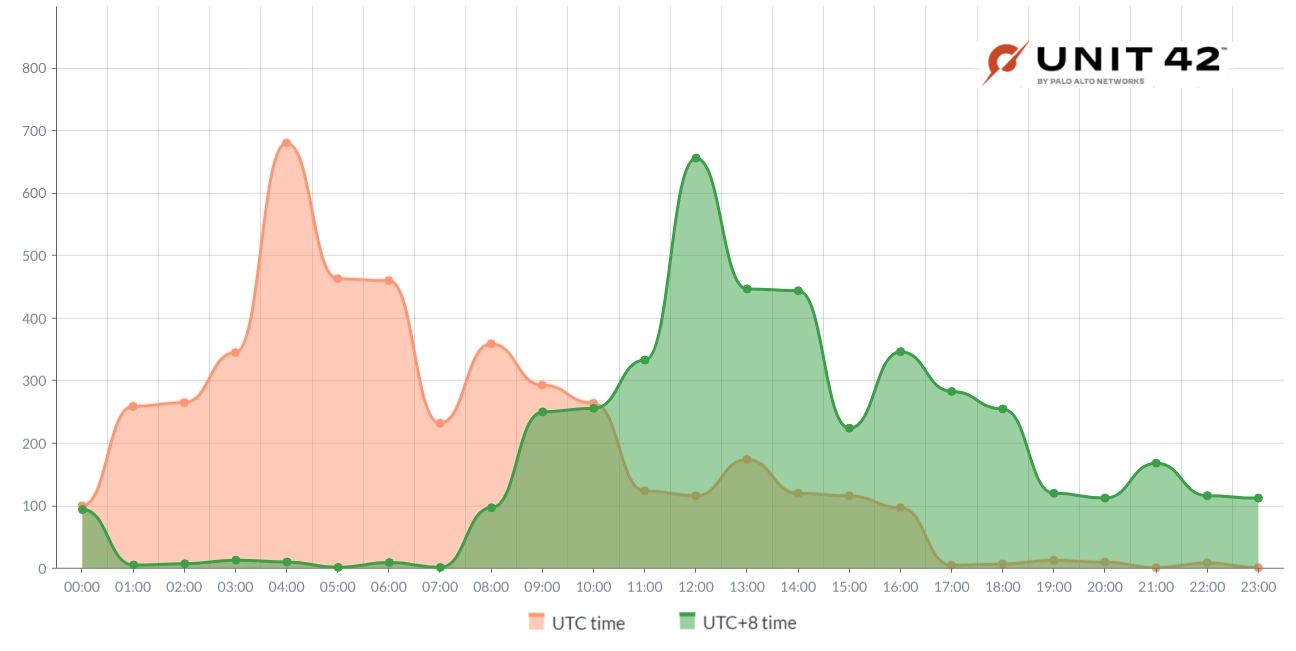

- Activity time frame: Statistical breakdown analysis of the hands-on-keyboard interactive activity of the threat actors, corresponds to 09:00-17:00 working hours in UTC +8. This corresponds to several Asian countries, including China. Historically, many Chinese nation-state threat actors have been observed operating in this time frame.

- Linguistic artifacts: Several tools and files dropped by the threat actors included numerous comments and debug strings in Mandarin, suggesting that the scripts’ creators may be Mandarin-speaking individuals.

- Tools and malware commonly used by Chinese APTs: Aside from the unique tools and malware, the threat actor also extensively used tools that are popular among Chinese threat actors, such as:

- Customized Gh0st RAT samples

- PlugX

- Htran

- China Chopper

While any threat actor can use these tools, they are mostly observed being used (especially together) in attacks involving Chinese threat actors.

- Use of Chinese VPS: The attackers used Chinese VPS providers, such as Cloudie Limited and Zenlayer, for several of their C2 servers.

Conclusion

The exfiltration techniques observed as part of Operation Diplomatic Specter provide a distinct window into the possible strategic objectives of the threat actor behind the attacks. The threat actor searched for highly sensitive information, encompassing details about military operations, diplomatic missions and embassies and foreign affairs ministries.

Our research spanned over a year and tightly monitored this activity, revealing that the threat actor (which we track as TGR-STA-0043) possesses potential motivation and modus operandi aligned with Chinese APT groups.

Besides using a rare set of tools TGR-STA-0043 stands out for its persistence and adaptability. The threat actor unabashedly resumes operations even after exposure, displaying a flagrant element to its nature.

Notably, TGR-STA-0043 continues to leverage known vulnerabilities in internet-facing servers. This underscores the need for heightened vigilance and fortified cybersecurity measures across global governments and organizations.

A resilient defense mechanism is not only essential for thwarting evolving cyberthreats but also for preserving the confidentiality, integrity and availability of critical information. In cultivating a strong security posture, nations can better safeguard their interests, protect against potential vulnerabilities and ensure the overall resilience of their cybersecurity frameworks.

Protections and Mitigations

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with this group:

- WildFire cloud-delivered malware analysis service accurately identifies the known samples as malicious.

- Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced DNS Security identify domains associated with this group as malicious.

- Cortex XDR and XSIAM are designed to:

- Prevent the execution of known malicious malware, and also prevent the execution of unknown malware using Behavioral Threat Protection and machine learning based on the Local Analysis module.

- Protect against credential gathering tools and techniques using the new Credential Gathering Protection available from Cortex XDR 3.4.

- Protect from threat actors dropping and executing commands from web shells using Anti-Webshell Protection, newly released in Cortex XDR 3.4.

- Protect against exploitation of different vulnerabilities including ProxyShell and ProxyLogon using the Anti-Exploitation modules as well as Behavioral Threat Protection.

- Detect post-exploit activity, including credential-based attacks, with behavioral analytics, through Cortex XDR Pro.

- Prisma Cloud Compute and WildFire integration can help detect and prevent malicious execution of the Specter backdoor within Windows-based VM, container and serverless cloud infrastructure.

If you think you might have been impacted or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Malware

TunnelSpecter

Loader:

- 0e0b5c5c5d569e2ac8b70ace920c9f483f8d25aae7769583a721b202bcc0778f

Encrypted payload

- 62dec3fd2cdbc1374ec102d027f09423aa2affe1fb40ca05bf742f249ad7eb51

Decrypted payload:

- 22d556db39bde212e6dbaa154e9bcf57527e7f51fa2f8f7a60f6d7109b94048e

Mutex:

- “blogs.bing.com”

SweetSpecter

Loader:

- 0b980e7a5dd5df0d6f07aabd6e7e9fc2e3c9e156ef8c0a62a0e20cd23c333373

Encrypted payload:

- 8198c8b5eaf43b726594df62127bcb1a4e0e46cf5cb9fa170b8d4ac2a4dad179

Decrypted payload:

- 0f72e9eb5201b984d8926887694111ed09f28c87261df7aab663f5dc493e215f

Gh0st RAT

- d5a44380e4f7c1096b1dddb6366713aa8ecb76ef36f19079087fc76567588977

Infrastructure

Domains

- home.microsoft-ns1[.]com

- cloud.microsoft-ns1[.]com

- static.microsoft-ns1[.]com

- api.microsoft-ns1[.]com

- update.microsoft-ns1[.]com

- labour.govu[.]ml

- govm[.]tk

IPs

- 103.108.192[.]238

- 103.149.90[.]235

- 192.225.226[.]217

- 194.14.217[.]34

- 103.108.67[.]153

Additional Resources

- Through the Cortex XDR Lens: Uncovering a New Activity Group Targeting Governments in the Middle East and Africa

- Space Pirates: analyzing the tools and connections of a new hacker group

- Operation Iron Tiger: Exploring Chinese Cyber-Espionage Attacks on United States Defense Contractors [PDF]

- Uncovering DRBControl: Inside the Cyberespionage Campaign Targeting Gambling Operations [PDF]

- Operation Earth Berberoka: An Analysis of a Multivector and Multiplatform APT Campaign Targeting Online Gambling Sites [PDF]

- Storm Cloud Unleashed: Tibetan Focus of Highly Targeted Fake Flash Campaign

- Holy water: ongoing targeted water-holing attack in Asia

- Operation Exorcist: 7 years of targeted attacks against the Roman catholic church [PDF]

- New Tool Set Found Used Against Organizations in the Middle East, Africa and the US

Appendix A: Main TTPs Observed in Operation Diplomatic Specter

As part of our observations of Operation Diplomatic Specter, we saw a distinctive set of TTPs. These TTPs indicate a high level of coordination, technical skill and determination – characteristics often associated with a nation-state threat actor. We previously wrote a deep technical analysis of the flow of the attack and the main TTPs.

Overview of TGR-STA-0043’s Tools and Malware

Table 1. TGR-STA-0043’s tools and malware.

A review of the main TTPs follows:

Targeted Data Exfiltration From Exchange Servers

In the context of targeted data exfiltration, TGR-STA-0043 exhibited a meticulous approach, particularly when abusing the Exchange Management Shell for stealing hundreds of emails and adding PowerShell snap-in (PSSnapins) to steal emails through a script. The threat actor strategically used those techniques to steal sensitive emails by employing specific keywords for data identification. Those keywords served as critical indicators enabling us, as researchers, to gain a precise understanding of the information targeted by TGR-STA-0043.

Credential Theft Using Network Providers

Within the realm of credential theft, TGR-STA-0043 showcased a variety of credential theft methodologies. While deploying well-known techniques such as Mimikatz and dumping the Sam key, the threat actor also introduced an uncommon credential theft tactic.

This novel approach involved the execution of a PowerShell script to register a new network provider, a method recognized as a proof of concept (PoC) named NPPSpy, and alternatively known as Ntospy by Unit 42. This technique is rare and has been reported only a handful of times in the past.

In-Memory VBS Implant

To infiltrate the network, TGR-STA-0043 strategically focused on exploiting vulnerabilities within Microsoft Exchange servers and public-facing web servers. The threat actor successfully gained access to specific targeted environments through the deployment of in-memory VBScript implants. This tactic not only underscored TGR-STA-0043's technical proficiency but also highlighted their ability to execute web shells in a clandestine manner on-the-fly, while attempting to bypass security mitigations.

Debut of the Yasso Penetration Tool Set

The emergence of a relatively new penetration testing tool set, Yasso, marked a shift in the tactics employed by TGR-STA-0043. This tool set encompassed a range of functionalities, including the following:

- Scanning

- Brute forcing

- Remote interactive shell capabilities

- Arbitrary command execution

What set Yasso apart was its unique feature set, incorporating powerful SQL penetration functions and database capabilities. Until the time of this article, this had not been publicly reported as being used in the wild by another threat actor.

Appendix B: Additional Technical Details on the Backdoors

TunnelSpecter

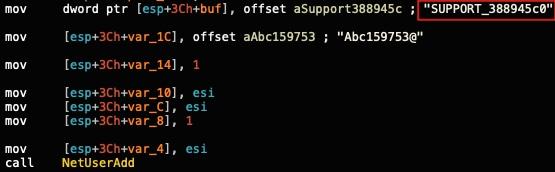

TunnelSpecter is a previously undocumented custom backdoor that the threat authors specifically customized for the target. Figure 8 shows that threat authors hard-coded this backdoor with a unique username, SUPPORT_388945c0. Notably, this username is a deliberate attempt to mimic the default account SUPPORT_388945a0, commonly associated with the Windows Remote Assistance feature.

An indication of the tailored nature of this malware is the preemptive creation of the same account (SUPPORT_388945c0). The threat actor created this account using a web shell within the compromised environment several weeks prior to the deployment of TunnelSpecter. The threat actor used TunnelSpecter to create the user, in the event that they failed to create it using the web shell. They then added the user (newly or previously created) to the Administrators group.

The main functionality of TunnelSpecter includes:

- Fingerprinting the infected machine and creating a unique identifier for each infected host, based on the CRC32 hash of the machine's cpuid value.

- Executing arbitrary commands by implementing a remote command-line interface. The supported commands can gather different information about the infected machine, such as the operating system version or host details.

- DNS tunneling C2 communication while encrypting communication using a hard-coded Caesar cipher on top of hex encoding. When transmitting data, TunnelSpecter prepends the unique machine identifier followed by a predetermined flag (b, c, d or z) and then the stolen data content. Figure 9 below shows this communication.

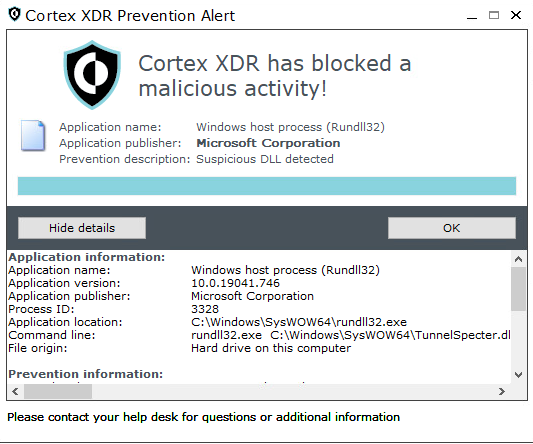

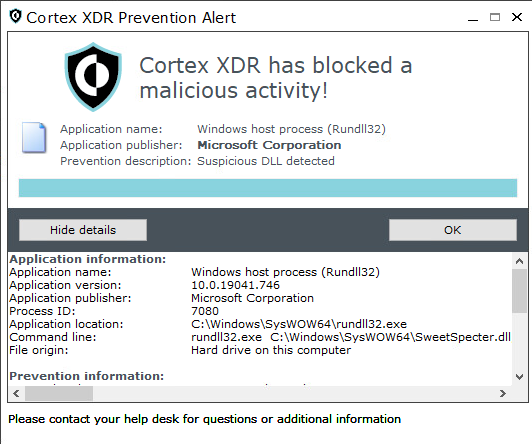

As shown in Figure 10, Cortex XDR prevented TunnelSpecter, recognizing it as a suspicious DLL.

Although we could not see a clear similarity between TunnelSpecter and Gh0st RAT, the malware shared similarity with the second backdoor discovered, SweetSpecter (described below).

SweetSpecter

Based on our analysis of the SweetSpecter malware, we believe it was written by the same author as TunnelSpecter. We found that it shares code similarities with TunnelSpecter and SugarGh0st RAT. This RAT is a relatively new variant of Gh0st RAT that emerged in November 2023 and that researchers at Talos observed targeting governments in Asia.

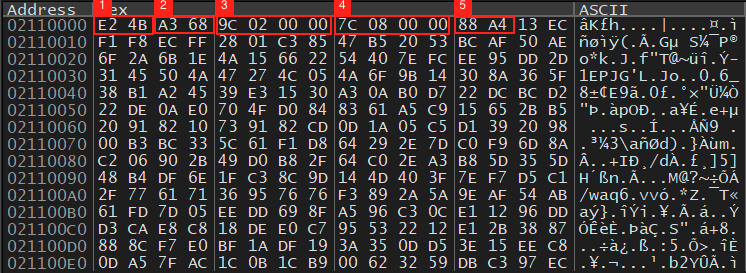

SweetSpecter implements Gh0st RAT’s known TCP communication scheme by sending a zlib compressed TCP packet to the command and control server. SweetSpecter also performs add and xor operations with the value 0x5f to add an encryption layer and thwart network-based signatures.

The “Gh0st” header is absent in this variant, and it is randomized instead based on the seed value received from GetTickCount. Figure 11 below shows an example of the transmitted data:

- The aforementioned random value.

- The random value from (1) XORed with 0x2341, another value hard-coded in SweetSpecter.

- The length of the compressed buffer including the preliminary 12 header bytes.

- The length of the decompressed buffer.

- The zlib magic bytes 0x789c that are added by and XORed with 0x5f.

Similarities with SugarGh0st RAT include:

- Using the HKLM\SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\ODBC registry key

- Using the GPINFO registry key and default value as a second campaign identifier

- Campaign ID format, using a string representing a month and a year (i.e., 2023.03) as shown in Figure 12

Finally, similarities with TunnelSpecter include:

- Using the HKLM\SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\ODBC registry key

- Generating the same user identifier by using the cpuid command

- Generating a mutex containing a domain name

- Similar initial system profiling and data sent to the C2

As shown in Figure 13, Cortex XDR prevented SweetSpecter, recognizing it as a suspicious DLL.

Appendix C: Additional Details on the Attribution to the Chinese Nexus

Infrastructure

Over the span of a year, we have been tracking and monitoring the infrastructure intricacies related to TGR-STA-0043. We noticed the changes in the C2 servers used by the threat actor, and we monitored these alterations.

In addition, we were able to uncover additional servers that are part of this complex operational infrastructure by pivoting on strategic data points, based on the already established knowledge of the infrastructure.

Our investigation revealed indications that threat actors employed a substantial portion of the correlated infrastructure, either presently or historically, as C2 servers for two prominent pieces of malware: PlugX and Trochilus RAT. These two pieces of malware (especially PlugX) are largely associated with Chinese threat actors. However, other threat actors can access and use them as well.

As depicted in Figure 14 below, we found multiple IP addresses related to the infrastructure, as well as domains and subdomains. A particularly noteworthy facet of our observations pertains to the threat actor's deliberate endeavors to assume the guise of both legitimate Microsoft servers (e.g., *.microsoft-ns1[.]com) and governmental entities. For example, *.govu[.]ml masquerades as a Mali-government address. (The threat actor’s impersonation does not imply any issues with the legitimate servers or governmental entities.)

Overlaps

As shown in the Maltego graph above, there are multiple overlaps between the infrastructure leveraged in Operation Diplomatic Specter and different operations, all associated with Chinese APTs.

IP Address Overlaps

The first overlap observed involves the IP address 192.225.226[.]217, used as one of the main C2 servers for the threat actor to communicate with at least one target. This IP was also observed in three different operations:

- Space Pirates, which was not formally attributed to any specific group, but it was attributed to Chinese threat actors

- Operation Iron Tiger [PDF], which was attributed to Iron Taurus

- Operation Exorcist [PDF], which was not formally attributed to a specific Chinese APT, though the authors of that report found overlaps with Stately Taurus (aka Mustang Panda)

SSL/TLS Certificate Overlaps/Pivoting

The other overlaps observed are related to the use of the same SSL certificate (SHA256: 3d74df40e3d2730941ff64f275217ae6d46b20d7fbbd04123bc156daf8f6e85c). This certificate was observed in multiple servers, some of which were overlapping with different activities, all associated with Chinese APTs.

The certificate pivoting led to the following IP addresses overlaps:

- The IP address 27.255.79[.]17 resolves to the domain poer.whoamis[.]info. It was mentioned in the context of Operation Earth Berberoka [PDF], which was attributed to Iron Taurus. It was also mentioned in connection to Starchy Taurus (aka Winnti).

- The IP address 108.61.178[.]125 that resolves to airjaldinet[.]ml, was mentioned in two operations: Storm Cloud and Holy water. These two operations were linked to Chinese APTs with different confidence levels, but they were not attributed to any specific group. In addition, the IP address 192.225.226[.]196, resolves to safer.ddns[.]us. It was also mentioned in the analysis of Operation Exorcist [PDF] mentioned above.

Activity Time Frame

During our analysis of compromised assets, we successfully traced the time frame of the threat actor's interactive sessions, focusing on hands-on-keyboard commands received from web shells and backdoors. Extensive mapping of the activity's working hours over several months revealed a notable and consistent pattern.

Figure 15 below shows our findings indicate a strong alignment with a standard 9-to-5 workday within the UTC+8 time zone. This time frame notably corresponds to the working hours of several Asian countries, including but not limited to China.

Linguistic Artifacts

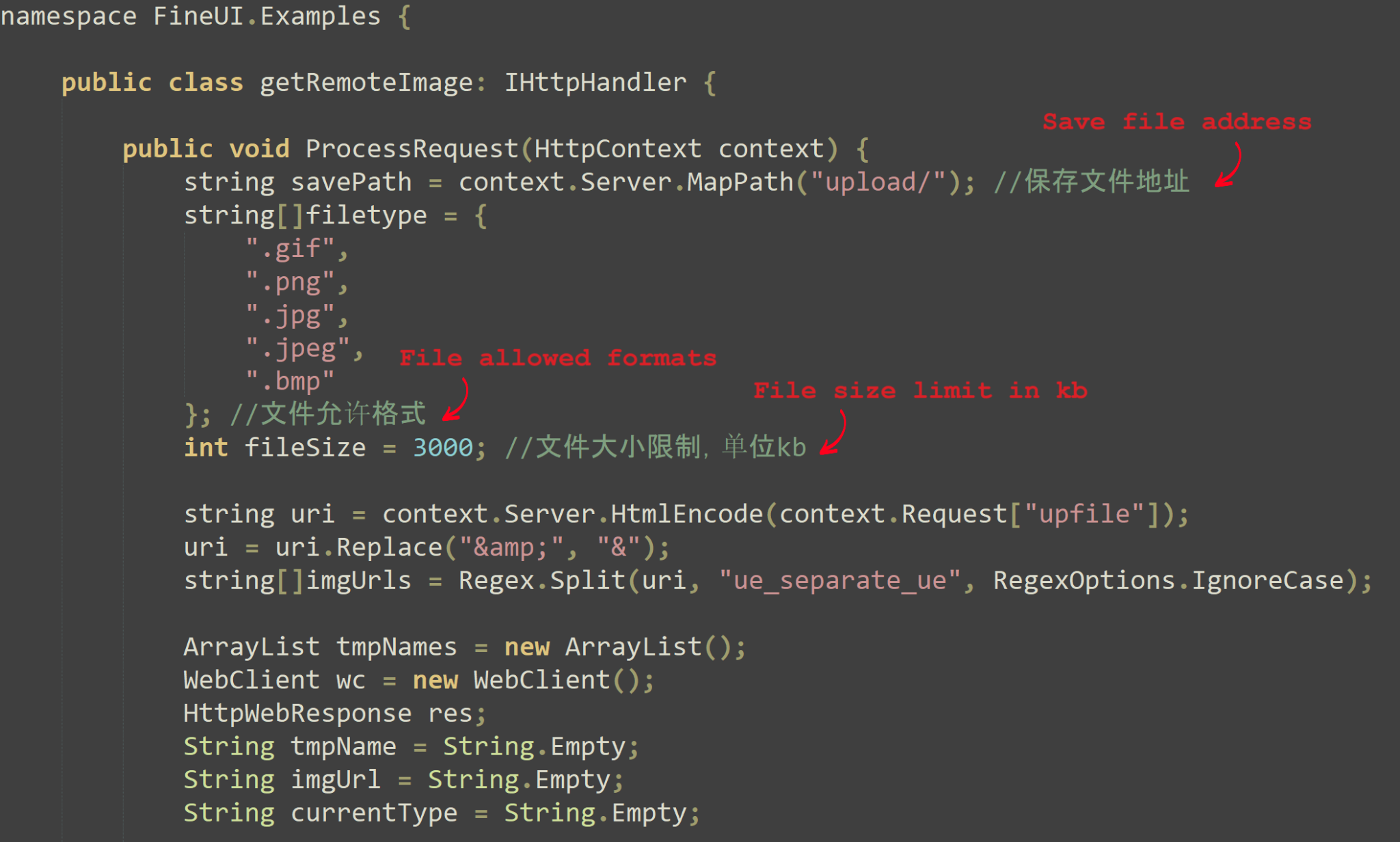

During our investigation, we acquired several scripts and files that prominently feature numerous comments and debug strings in Mandarin, suggesting that the scripts’ creators are Mandarin-speaking individuals. One of those files is a web shell found on one compromised environment.

Further inspection of the code revealed a subtle resemblance between the code in the web shell we obtained and a GitHub repository of a penetration testing PoC tool. This tool is named GetShell, and was created three years ago.

It is possible that the web shell used by the threat actor borrowed code from this existing repository. However, the threat actor appears to tailor the code to suit specific targets, modifying it based on the nature of the targeted data.

In particular, we identified a customized version of this web shell deployed on the Exchange servers of one of the targets. This modified version, named ManagementMailboxPicker.aspx, demonstrated functionalities focused on file uploads and not limited to images, as shown in Figure 16.

Our analysis suggests that the threat actor leveraged this web shell to manage the upload of files, potentially .pst and archive files containing email data. The nomenclature ManagementMailboxPicker.aspx further implies its role in the manipulation of mailbox-related activities.

Tools and Malware Commonly Used by Chinese APTs

Another facet of strengthening the connection to a Chinese threat actor lies in the tools and malware employed during the operation. We observed multiple tools and malware commonly associated with a diverse range of Chinese threat actors, including:

- Gh0st RAT

- PlugX

- China Chopper

- Htran

While many Chinese threat actors seem to favor these tools, it's crucial to emphasize that the mere presence of these tools and malware does not singularly establish a link or attribution to Chinese threat actors. While these tools are prevalent among such actors, they are not exclusive to this context and are accessible for use by other threat actors as well.

Use of Chinese VPS

The attackers used Chinese VPS providers, such as Cloudie Limited and Zenlayer, for several of their C2 servers. It is interesting to note that some of those VPS services are offered in Yuan only. The fact that the service is offered only in Yuan can strengthen the connection to Chinese operators, but of course it’s not limited to them.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh