Marketplace fraud is nothing new. Cybercriminals swindle money out of buyers and sellers alike. Lately, we’ve seen a proliferation of cybergangs operating under the Fraud-as-a-Service model and specializing in tricking users of online marketplaces, in particular, message boards. Criminals are forever inventing new schemes for stealing personal data and funds, which are then quickly distributed to other scammers through automation and the sale of phishing tools. This article explores how these cybergangs operate, how they find and fool victims, with a special look at a campaign targeting users of several European message boards.

Ways to deceive message board users

There are two main types of message board scams.

- The first one is when a scammer impersonates the seller and offers to ship an item to the buyer. When the buyer inquires about the terms of delivery and method of payment, the scammer (in the role of the seller) asks for the buyer’s full name, address and phone number, and for online payment. If the victim agrees, they are sent a phishing link to pay for the order (in a third-party messenger or in a dialog box on the message board itself, if the site does not block such links). As soon as the user enters their card details on the fake site, they go straight to the fraudster, who debits the available balance.

This type of fraud is known as scam 1.0 or a buyer scam, because the attacker poses as the seller to deceive the buyer. It is considered outdated as most message board users are aware of it. Besides, the method involves waiting around for a buyer to take an interest in the item on offer. - Alternatively, the scammer can pose as the buyer and deceive the seller by persuading the seller to dispatch the item and collect payment by “secure transaction”. As in scam 1.0, the attackers send a phishing link to the duped seller via a third-party messenger or directly on the message board. The linked page requests payment card details. If the seller enters these, supposedly to receive payment, the attacker debits all the money from the card.

This is known as scam 2.0 or a seller scam, because the attacker deceives the seller posing as the buyer. This type of scam is more common than the first, since fewer users are familiar with it, so the chances of finding a victim are greater. What’s more, in scam 2.0 the attacker proactively searches for victims, instead of waiting for one to appear, which speeds up the operation.

In both cases, clicking the link opens a phishing site – a near exact replica of a real trading platform or payment service with just one tiny difference: all the data you enter there will fall into cybercriminal hands. Now for a closer look at the scam 2.0 scheme targeting sellers.

How attackers choose their victims

Scammers have several criteria for selecting potential victims. Primarily they are drawn to ads that sellers have paid to promote. Such ads usually appear at the top of search results and are marked as sponsored. They attract scammers for two reasons: first, a seller who pays for promotion is more likely to have money, and second, they are probably looking for a quickish sale.

Besides the sponsored label, attackers look at the photos in the ad: if they are of professional quality, it is most likely an offer from a store. Scammers are not interested in such ads.

Lastly, attackers need sellers who use a third-party messenger and are willing to provide a phone number. This information becomes known only after contact is made.

How the victim is deceived

The main goal is to persuade the victim to click a phishing link and enter their card details. Like any buyer, the scammer opens the conversation with a greeting and an inquiry about whether the offer is still on the table. After that, the threat actor asks the seller various questions about the product, such as its condition, how long ago they purchased it, why they want to sell it, and so on. Experienced scammers ask no more than three questions to avoid arousing suspicion.

Next, the attacker agrees to buy the item, but says they cannot pick it up in person and pay in cash because, say, they are out of town (here the scammer can get creative), and then asks if delivery with “secure payment” is acceptable.

To deflect potential questions from the seller, the scammer explains the payment scheme in detail, roughly as follows:

- I pay for the item on [name of site].

- You get a link to receive the money.

- You follow the link and enter your card details to receive the payment.

- Once you receive the money, the delivery service will contact you to establish your preferred shipping method. Shipping will already be paid for. The delivery service will pack and document the item for you.

If the victim starts to quibble about the payment method, the scammer simply vanishes so as not to waste time. If the seller wants to continue negotiations on the marketplace’s official website, the attacker concludes they smell a rat and will be unlikely to click the phishing link, and so stops replying and begins the search for a new victim.

If, however, the victim clicks the link and enters their card details, the scammers siphon off all available funds. The price of the item is irrelevant: even if the amount asked for in the ad was insignificant, the attackers will steal whatever they can.

What phishing pages look like

In the scam 2.0 scheme, there are two main flavors of phishing site: some mimic the marketplace with the victim’s ad, others a secure payment service such as Twin. Below is an example of a phishing ad and the original on the official site.

As we see, the scammers have produced a near exact copy of the marketplace interface. The fake page differs from the original only in minor details. In particular, instead of the Inserent kontaktieren (“Contact advertiser”) button, the phishing page shows a Receive 150 CHF button. Clicking this button opens a page with a form for entering card details.

If the original link opens a copy of a secure payment service, the card data entry form appears directly on this page, without additional redirections.

Cybergangs

Recently, whole groups of scammers specializing in message boards have gained widespread notoriety. Practicing both types of fraud (scam 1.0 and scam 2.0), they unite criminal masterminds, support teams, and low-level players.

We carried out an in-depth study of one such gang targeting message board users in Switzerland. Drawing on this example, we will show the internal structure and organization of activities in such structures.

A cybercriminal group may include the following roles:

- Topic starter (TS) is the team’s founder and main administrator.

- Coder is responsible for all technical components: Telegram channels, chats, bots, etc.

- Refunder is a scammer who handles tech support chats on phishing sites. They help coax the victim into entering their card details, which is the attackers’ ultimate goal. The name “refunder” comes from the fact that the victim is directed to such a “specialist” if they are unhappy about the debit and want a refund.

- Carder has the task of withdrawing money from the victim’s bank account. As a rule, having received card data, the carder uses it to pay for various goods, services, loans, etc. The process of paying for purchases with someone else’s card is called carding.

- Motivator provides moral support to scammers. Their task is to make sure the gang remains focused and doesn’t lose heart. The motivator offers podcasts and support in personal messages – a chance to discuss any problems, including personal issues unrelated to fraud. Only large operations have the funds to engage such an “employee”. The motivator works for a percentage of the stolen money.

- Marketer is responsible for ad campaigns and the design and appearance of bots and accompanying materials – mainly on dark web platforms and Telegram channels for scammers. Advertising is needed to attract new workers.

- Worker is a scammer who directly deceives victims: finds ads, responds to them, persuades the victim to follow a phishing link, etc. Workers differ from regular scammers only in that they work for a group and make use of its tools and support. As payment, workers receive the funds they steal, minus a commission. The process of defrauding victims is called work.

- Mentor is an experienced worker assigned to a newcomer.

- Consummator is a woman who encourages a man to buy gifts and scams money out of him. This role is offered to all women who join closed groups where scammers communicate with each other.

Other scammer terms worth highlighting are:

- A trusting user who has already been deceived is called a mammoth.

- The amount of money on the card whose details the victim entered on a phishing website is called logs.

- The amount debited from the victim’s card is called profit.

Groups communicate in closed groups and channels on Telegram, where they search for new workers, support bots for creating phishing links, track clicks on sent links, as well as keep statistics on each case and the profits of individual workers and the group as a whole.

Fraud-as-a-Service

Cybergangs operate under the Fraud-as-a-Service model, in which the main service consumers are workers. Organizers provide functioning services (channels/chats/bots on Telegram, phishing sites, payment processing, laundering/debiting of funds), as well as moral support and “work” manuals. In return, they take a commission from each payment.

Which countries are targeted by message board scams?

Scam 1.0 and scam 2.0 appeared several years ago, and both schemes can still be found on Russian-language message boards. But scams aimed at the Russian segment are considered old-hat among experienced scammers, since Russian users are tuned in to such schemes and there is a high risk that the attackers will be found and arrested. Therefore, scammers are switching to other countries.

The group at the center of our investigation is primarily focused on Switzerland. In their chat, the scammers cite the reason as the lower risk of getting caught and Swiss-based users’ relative unfamiliarity with this type of scam. In addition, before placing ads or responding to them, the scammers get to know the target country’s market and basic facts about it. For example, what languages and dialects are spoken there. This is to address the victim in their local tongue so as to win trust more easily. According to 2023 data, over two-thirds of the Swiss population aged 15 and older are fluent in at least two languages.

The gang under study also operates in Canada, Austria, France, and Norway.

Work manual

We analyzed the instructions that the group gives to new workers and found out how they get started. First of all, on the dark web, the worker buys accounts on message boards, which they will then scour for victims. Attackers buy accounts rather than create them, since registering on sites carries more risks. That done, the worker creates an account in a third-party messenger. This account is used for communication with the victim. Some users themselves ask for a number to make contact via messenger; in other cases, it is the worker who offers it to reduce the risk of getting banned on the marketplace. Virtual phone numbers are used for registration.

The next step is for the worker to find a proxy server that will provide anonymity and confidentiality. When connecting through this, the marketplace sees the server’s IP address and other information, which allows the attacker to hide their identity data. A proxy is generally considered good if the account is not banned immediately after registration. If a worker uses a VPN, for instance, their accounts will get banned very quickly: connecting via VPN entails a frequent change of IP address and geolocation, which is why sites often identify such accounts as bots.

Besides instructions for getting started, the manual contains templates shared by experienced gang members. The novice worker can use the templates to persuade a victim to make a deal or assuage any concerns about the proposed payment method.

The manual also contains instructions on how to bypass restrictions imposed by sites. Message boards are constantly updated to strengthen internal security, so it’s increasingly difficult for workers to use stock phrases in communicating with users. For example, in November 2023, one popular marketplace banned payments through Tripartie, a commonly used platform for secure transactions in Switzerland, and began blocking accounts for mentioning this system in chats. To get around this update, workers deliberately misspell the name Tripartie. More experienced workers use the Cyrillic alphabet to make the name of the payment system unreadable to the site’s security systems.

Monetizing stolen cards

If the seller enters their card details, the worker sends the data to the carder, who withdraws money from the card within the established limits. There are different ways to do this: by purchasing expensive devices, transferring money to an e-wallet such as PayPal, etc. The carder may also try to have a credit or loan issued in the card owner’s name, or open a deposit. To do this, they use online banks that do not require SMS verification. Some institutions may ask for a passport scan, in which case the carder uses passport data that was stolen or taken from people with no fixed abode. Although this data has nothing to do with the card owner, scammers rely on the fact that online banks do not always check that the passport and card belong to the same person.

Fraud automation with Telegram bots

To simplify the job of workers, the group deploys a phishing Telegram bot. This automates the process of creating phishing pages and communicating with victims, as well as tracking the scammers’ progress. The bot’s main page has buttons for creating a phishing link, viewing a personal profile, quick access to the group’s chats and channels, plus settings.

Clicking the button to create a phishing page lets the user select a country for which a unique link will be generated.

Next, the worker specifies the name of the item that the victim wants to buy (if the victim is a buyer) or sell (if a seller).

With this data the bot is able to create a full copy of the original ad, but on the phishing page. In addition, the worker feeds information from the ad (photo, price, description, etc.) into the bot, so that the victim feels like they are on the original page.

After filling in all the data, the bot provides phishing links in all languages for the target country, for all available message boards, and for both scam types (buyer and seller), from which the worker chooses the most suitable.

Here the scammer can message the victim by email, messenger or text. The contact information is obtained from the target’s profile on the site, or is wheedled out in a private chat.

After a successful phishing attack, the worker can view their in-bot profile, which displays personal information: ID, handle, card balance, amount earned by the worker personally and by the group as a whole.

Also inside the bot, it is possible to make direct contact with a mentor and to earn additional revenue through the “refer-a-friend” scheme.

What the phishing links look like

The phishing links that the group creates with its Telegram bot are built along the same pattern:

- domain/language/action/ad number

The domain most often contains the full or partial name of the message board that the phishing page imitates, but this is not a mandatory component.

Language information may vary, as it depends on the target country. In case of Switzerland, there are the following options: en, it, fr, de.

The action is what the victim purportedly needs to do: pay for the item or receive payment. This element takes one of two values: pay (if the scammer is posing as a seller) or receive (if as a buyer).

The phishing link always ends in the ad number, identical to the original.

Bot updates

Cybergangs are constantly tweaking and updating their Telegram bots. They add new information useful for workers and expand the arsenal of scam automation tools.

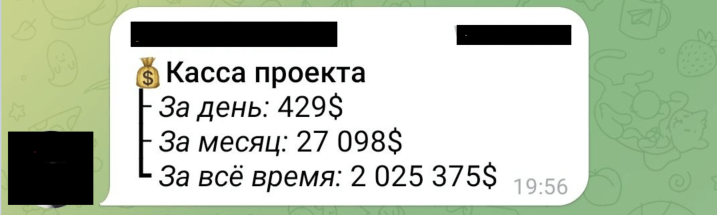

During our observation of the Telegram bot under study, information appeared about the group’s income for different periods: per day and for its entire existence, as well as information about the worker’s income per week and per month.

The next update added detailed information about mentors and their workload. In total, the group has five mentors, who oversee more than 300 workers. At the time of posting, the scammers’ group on Telegram had more than 10,000 members.

The most experienced workers with profits in excess of 20,000 euros can become mentors. This involves submitting an application to the head mentor for consideration. Mentors receive a percentage of their mentees’ earnings. The size of the commission is set by mentors themselves, and goes up with experience.

Besides the modified interface, the way in which links are created was updated, with an expanded list of platforms targeted by phishing.

What happens after clicking a link

The link from the bot points to a phishing site, the address of which may differ from the original by just one letter. The page is a full copy of the original ad, including the site logo and name, price and description of the item of interest.

Phishing ad aimed at deceiving the buyer. For the seller, the page is the same, only instead of a Pay button there will be a Receive button.

When the victim clicks the phishing link, the worker receives a notification in the bot about this activity. The notification prompts the scammer to check if the victim is online (that is, whether they’ve opened the phishing link) and, if necessary, to start a chat. Such notifications are created to simplify the worker’s tasks and speed up the response.

When the victim enters card details, the carder immediately uses them, and a notification is sent to the group’s general chat about receipt of a new payment. The message specifies the stolen amount, plus information about how much of it will go to the carder and the worker. The worker’s share is automatically credited to their account specified in the bot settings. The message from the bot also contains the name of the user who pays the worker their profit. This is so that scammers themselves do not get cheated, as there have been cases of workers, under the guise of payment, swindling money out of “colleagues” or asking to borrow a certain sum and not returning it.

Late in the day, a notification is sent to the general chat about the amount earned by the entire group for the day, month and whole period of operation. The group in question was established in August 2023. It made its first profit 3 days and 17 hours later. Back then, it had 2,675 workers and receipts worth 1,458 USD.

Profit and statistics

We compiled statistics on the group’s activities for the period February 1–4, 2024, inclusive.

| Country | Total logs | Total profits |

| Canada | 1,084.999 CAD | 0 CAD |

| Switzerland | 50,431.17 CHF | 10,273 CHF |

| France | 850 EUR | 0 EUR |

| Austria | 2,900 EUR | 0 EUR |

In four days, the group earned 10,273 CHF (roughly 11,500 USD). At the same time, from the log amounts, we see the attackers could have stolen over 50,000 USD from Swiss cards alone. Why didn’t they? The main reason is that the carder does not work with logs worth less than 300 CHF (330 USD). This is most likely because total profits received from such logs will be less than the cost of debiting them. Moreover, withdrawing money from a card carries a high risk of detection, so carders are only interested in cards holding large sums of money. Lastly, some victims may have managed to block their cards before they fell into the carder’s hands, or entered incorrect data, which would have impacted the total amount of logs.

| Country | Number of logs |

| Switzerland | 65 |

| France | 6 |

| Austria | 4 |

| Canada | 4 |

Looking at the number of logs received, we see the most popular country is Switzerland. France comes second. In joint third place are Austria and Canada.

| Platforms | Number of logs | Total profits |

| 26 | 0 CHF | |

| Post.ch | 16 | 3,887 CHF |

| Tutti.ch | 16 | 2,434 CHF |

| Anibis.ch | 11 | 3,952 CHF |

In terms of message boards whose users were scammed, the most popular platforms among attackers were: Facebook, Post.ch and Tutti.ch. That said, logs from Facebook earned no profits for scammers. The most profitable platform was Anibis.ch, which lies in fourth place by number of logs; Post.ch is in second place, and Tutti.ch in third.

How not to swallow workers’ bait

Although message board scams are automated and production-lined, you can take protective measures.

- Trust only official sites. Before entering card details in any form, study the site address, make sure there are no typos or extra characters in the domain, and check when it was created: if the site is just a couple of months old, it is likely to be fraudulent. Safest of all is not to follow links to enter your data, but to type in the URL in the address bar manually or open it from bookmarks.

- When buying or selling goods on message boards, do not switch to third-party messengers. Conduct all correspondence in a chat on the platform. Such platforms typically use fraud protection and forbid sending suspicious links.

- Where possible, refuse payment in advance – pay only when you receive the item in good condition.

- Do not scan QR codes sent from untrusted sources.

- Do not sell goods “with delivery” if the platform has no such option. If the buyer is located in another city, choose a delivery service yourself, giving preference to large, reputable companies.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh