Many public blogs and conference talks have covered Windows telemetry sources like kernel callbacks and ETW, but few mention macOS and Linux equivalents. Although most security professionals may not be surprised by this lack of coverage, one should not overlook these platforms. For example, developers using macOS often have privileged cloud accounts or access to intellectual property like source code. Linux servers may host sensitive databases or customer-facing applications. Defenders must have confidence in their tools for these systems, and attackers must understand how to evade them. This post dives into endpoint security products on macOS and Linux to understand their capabilities and identify weaknesses.

Endpoint detection and response (EDR) agents comprise multiple sensors: components that collect events from one or more telemetry sources. The agent formats raw telemetry data into a standard format and then forwards it to a log aggregator. EDR telemetry data informs tools such as antivirus, but it also informs humans as they manually hunt for threats in the network.

This post should not be considered a comprehensive list of telemetry sources or EDR implementations. Instead, the following observations were made while reverse engineering some of the most popular macOS and Linux agents. Outflank tested the latest version of each product on macOS 14.4.1 (Sonoma) and Linux 5.14.0 (Rocky 9.3). After reviewing previous research, the author will describe relevant security components of macOS and Linux, present their understanding of popular EDR products, and then conclude with a case study on attacking EDR using this knowledge.

Notable EDR Capabilities

Although every product has its own “secret formula” for detecting the latest threats, nearly all EDR agents collect the following event types:

- Authentication attempts

- Process creation and termination

- File access, modification, creation, and deletion

- Network traffic

Outflank’s research primarily focused on these events, but this post will also cover other OS-specific telemetry.

Previous Research

Security researchers have covered Windows EDR internals in great detail. A quick Google search for “EDR bypass” or “EDR internals” will return an extensive corpus of blogs, conference talks, and open-source tools, all focused on Windows EDR. That said, most companies consulted by the author also deployed an EDR agent to their macOS and Linux systems. These agents are relatively undocumented compared to their Windows counterparts. This lack of information is likely due to the success of open-source tools such as Mythic and Sliver in evading out-of-the-box antivirus solutions (including those bundled with EDR).

Of course, there is full Linux kernel source code and Apple documentation, albeit not verbose, on stable macOS APIs. This alone does not give much insight into the workings of EDR agents, though, as it only describes the possible ways said agent might collect information on a system. One can glimpse some additional understanding by reviewing open-source projects, such as the outstanding Objective-See collection for macOS or container runtime security projects for Linux. Below is a list of projects that share functionality with EDR agents reversed by Outflank:

Even still, these projects do not fully replicate the capabilities of popular EDR agents. While each may collect a subset of the telemetry used by commercial products, none of these projects appeared to have the same coverage.

Telemetry Sources – macOS

Unsupported Options

In studying macOS internals, one might discover promising security components that commercial products do not use. For instance, many considered kernel extensions (KEXT) a de facto sensory component of EDR agents until Catalina (2019) phased them out completely. Michael Cahyadi’s post on the transition from kernel extensions to modern alternatives documents the work required to migrate from these frameworks.

Similarly, modern macOS (2016+) implements a standardized logging system called unified logging. Logs are categorized by subsystem (e.g., com.apple.system.powersources.source) and can be viewed with /usr/bin/log or the Console application. While unified log data is great for debugging, the logs are restricted with a private entitlement (com.apple.private.logging.stream), rendering them unusable to third-party EDR agents.

Endpoint Security API

Apple now recommends the Endpoint Security (ES) API for logging most events an EDR agent requires:

- Authentication attempts

- Process creation and termination

- File access, modification, creation, and deletion

The complete list of ES event types in Apple’s documentation follows a standard format: ES_EVENT_TYPE_<RESPONSE TYPE>_<EVENT TYPE NAME>.

The “response type” can be NOTIFY or AUTH, depending on whether the ES client must authorize an action. The “event type name” describes each event. (Examples will be discussed in the following sections.)

Plenty of open-source examples exist for those looking to write an ES API client, but executing them on modern macOS requires the developer to sign their executable with a restricted entitlement or disable SIP on the target system.

Network events are notably absent from the ES API. Instead, EDR agents can utilize an additional sensor that captures events using the NetworkExtension framework.

Following Apple’s deprecation of kernel extensions, events can be collected entirely from user-mode using the ES API and NetworkExtension framework. This differs from Windows and Linux, which rely heavily on kernel-mode sensors.

Examining ES Event Types

Red Canary Mac Monitor is a free, closed-source ES client. It uses a system extension, so the client must be embedded within its application bundle in Contents/Library/SystemExtensions/. In this case, the bundle’s entitlements can be listed using the codesign utility.

codesign -d --entitlements :- /Applications/Red\ Canary\ Mac\ Monitor.app/Contents/Library/SystemExtensions/com.redcanary.agent.securityextension.systemextensionThe output property list will vary depending on the target system extension, but all ES clients must have the com.apple.developer.endpoint-security.client entitlement.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "https://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>com.apple.application-identifier</key>

<string>UA6JCQGF3F.com.redcanary.agent.securityextension</string>

<key>com.apple.developer.endpoint-security.client</key>

<true/>

<key>com.apple.developer.team-identifier</key>

<string>UA6JCQGF3F</string>

<key>com.apple.security.application-groups</key>

<array>

<string>UA6JCQGF3F</string>

</array>

</dict>

</plist>ES clients must initialize the API using two functions exported by libEndpointSecurity.dylib: es_new_client and es_subscribe. The latter is particularly interesting because it indicates to the ES API which events the client should receive. Once a client of interest has been discovered, it can be instrumented using Frida (after disabling SIP). The es_subscribe function contains two parameters of interest: the number of events (event_count) and a pointer to the list of event IDs (events).

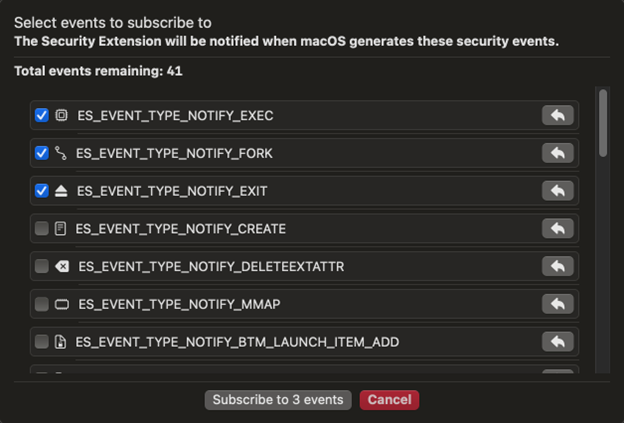

es_return_t es_subscribe(es_client_t* client, const es_event_type_t* events, uint32_t event_count);With this information, one can inject a target system extension process with Frida and hook es_subscribe to understand which events it subscribes to. The function will likely only be called when the system extension starts, so analyzing an EDR agent may require some creative thinking. Mac Monitor makes this step easy as the runtime GUI can update the list of events.

Outflank created a simple Frida script to hook es_subscribe and print the list of events, as well as an example Python script to create or inject the process.

Examining ES Event Types

Even with a list of event types, the actual data available to an ES client may not be clear. Outflank published an open-source tool called ESDump that can subscribe to any currently available event types and output JSON-formatted events to stdout.

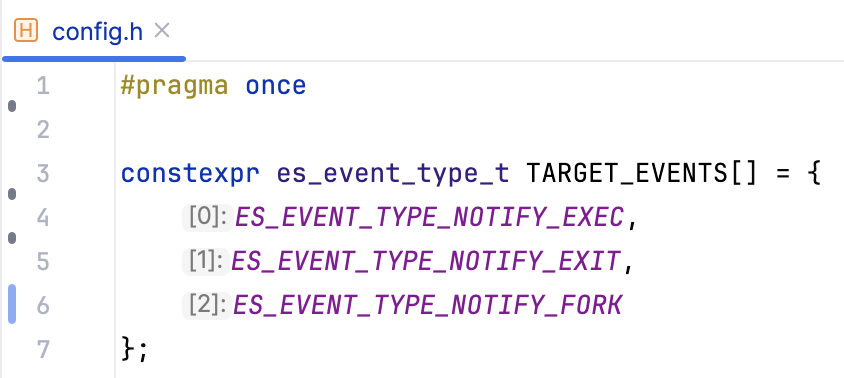

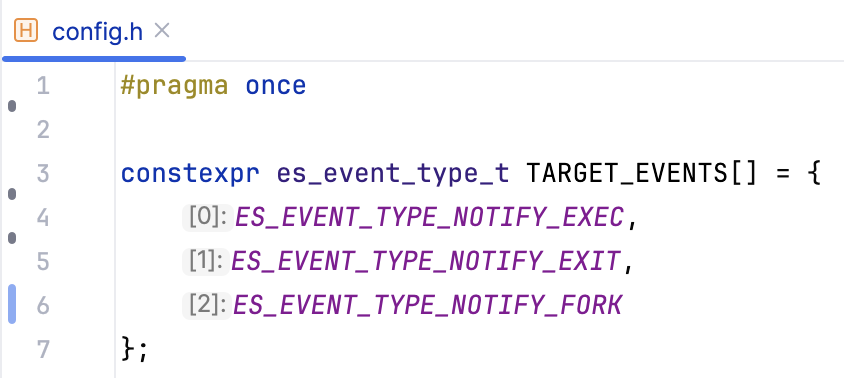

The list of event types is defined in config.h at compile-time. For example, the following config will subscribe to the event types selected in the previous section.

Compile the program and then copy it to a macOS system with SIP disabled. ESDump does not have any arguments.

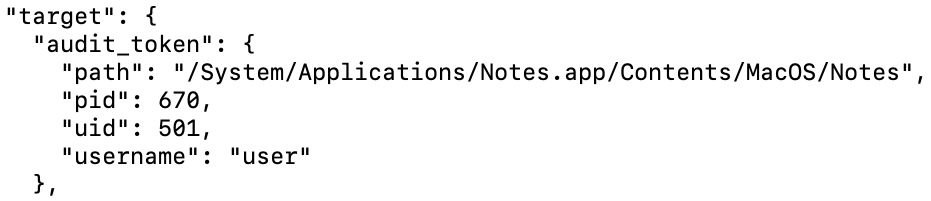

ESDump uses audit tokens to retrieve IDs for the associated process and user. The program resolves process and user names to enrich raw data.

NetworkExtension Framework

Unlike the ES API, the NetworkExtension framework does not have predefined event types. Instead, agents must subclass various framework classes to monitor network traffic. Each of these framework classes requires a different entitlement. The relevant entitlements provide insight into possible use cases:

- DNS Proxy – Proxy DNS queries and resolve all requests from the system.

- Content Filter – Allow or deny network connections. Meant for packet inspection and firewall applications.

- Packet Tunnel – Meant for VPN client applications.

In addition to the DNS request and response data, providers can access metadata about the source process, including its signing identifier and application audit token. Content filter providers can also access the process audit token, which is different from the application audit token if a system process makes a network connection on behalf of an application. In both cases, these properties are enough to find the originating process and user IDs to correlate network extension data with ES API events.

Analyzing Network Extensions

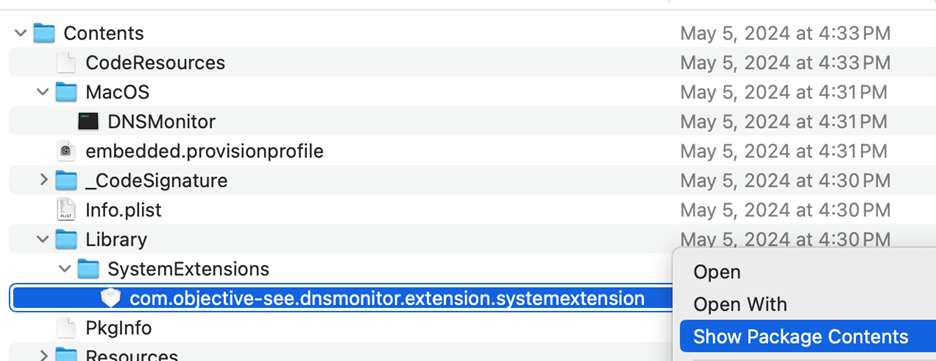

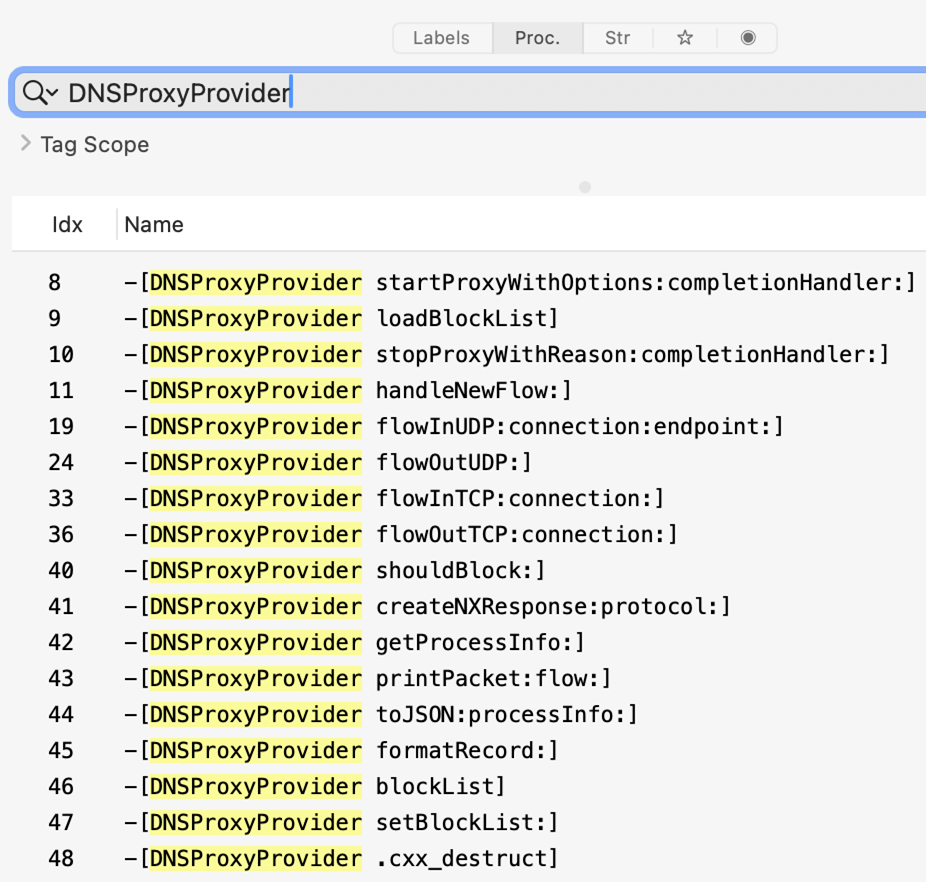

Discovering the network extension provider(s) an agent implements is simple, as they each require separate entitlements. DNSMonitor from Objective-See is an open-source DNS proxy provider. It uses a system extension, so the provider must be embedded within its application bundle in Contents/Library/SystemExtensions/.

Inside a system extension bundle, there will be a file at Contents/Info.plist containing information about its entitlements. The NetworkExtension key should be present, with a NEProviderClasses subkey that lists each provider implementation.

<key>NetworkExtension</key>

<dict>

<key>NEMachServiceName</key>

<string>VBG97UB4TA.com.objective-see.dnsmonitor</string>

<key>NEProviderClasses</key>

<dict>

<key>com.apple.networkextension.dns-proxy</key>

<string>DNSProxyProvider</string>

</dict>

</dict>Each provider type will also highlight the name of the associated class. This information is enough to start reversing an extension using a tool like Hopper.

Creating a Network Extension

While knowing the providers implemented by a macOS network extension is valuable, more is needed to understand the data available to the agent. Outflank released an open-source tool called NEDump that implements a content filter provider and writes JSON-formatted events to stdout. The application and system extension must be signed, even with SIP disabled, so the repository includes a signed release binary. As a system extension is utilized, the application must be copied to /Applications/ to function. No arguments are required to execute NEDump and start receiving event data.

Telemetry Sources – Linux

While Linux components are deprecated less often than macOS equivalents, most Linux EDR agents had comparable, modern implementations. For example, Auditd could provide the necessary telemetry for an EDR agent, but newer alternatives have better performance. In addition, only one program can subscribe to Auditd at a time, meaning the agent may conflict with other software. Both reasons sit among the most common EDR complaints, likely explaining why Outflank did not observe any products using these methods by default.

Kernel Function Tracing

The observed agents all utilized kernel function tracing as their primary telemetry sources. Linux offers several ways to “hook” kernel functions to inspect their arguments and context. Popular EDR agents used the following trace methods:

- Kprobes and Return Probes – Any kernel function (or address) that a client resolves can be traced using kernel probes. Function resolution requires kernel symbols to be available and likely requires different addresses for kernel versions or even distributions. Target functions may even be unavailable due to compile-time optimizations.

- Tracepoints – A “tracepoint” is a function call added to various functions in the Linux kernel that can be hooked at runtime. These work similarly to kprobes but should be faster and do not require function resolution. However, some target functions may not have a tracepoint.

- Raw Tracepoints – A “raw” tracepoint is a more performant alternative to any non-syscall or sys_enter/sys_exit tracepoint. These hooks can also monitor syscalls that don’t have a dedicated tracepoint.

- Function Entry/Exit Probes – Fentry and fexit probes act similarly to tracepoints, but they are added by GCC (-pg).

Kernel-Mode Programming

Traditionally, only loadable kernel modules (LKM) could use kernel tracing features. LKMs are similar to Windows drivers—crashes may result in unrecoverable kernel errors, raising similar stability concerns. Linux kernel versions 4.x implement an “extended” version of Berkeley Packet Filter to address these concerns called eBPF. This feature allows developers to load small, verifiable programs into the kernel. eBPF programs have material constraints, but they should mitigate the stability risks of LKM-based sensors. Only newer Linux kernel versions support eBPF and certain advanced eBPF features; customers may not have these versions deployed across their environments. This led many EDR vendors to offer two (or more!) versions of their Linux agent, each targeting a different kernel version.

Liz Rice from Isovalent wrote an excellent, free book on eBPF. The company also has a free eBPF lab on its website for those who prefer a hands-on approach. Many open-source projects demonstrate good examples of eBPF-based tracing. This post only covers the newest eBPF variant of each agent, but it is safe to assume that other variants collect similar information with a slightly modified eBPF or LKM-based sensor.

Analyzing eBPF Programs

Two components of eBPF-based sensors may provide insights into their implementation: programs and maps. Each eBPF program typically monitors a single kernel function and uses a map to communicate with the user-mode agent. Microsoft SysmonForLinux is a well-documented, open-source eBPF-based monitoring tool. It uses several tracepoints to monitor process, file, and networking events. Once installed, a complete list of currently loaded programs can be retrieved using bpftool with the bpftool prog list command. The results usually include unrelated programs, but the PIDs can identify relevant results, as seen below.

52: raw_tracepoint name ProcCreateRawExit tag ebba2584bc0537a4 gpl

loaded_at 2024-05-14T12:42:20-0500 uid 0

xlated 6912B jited 3850B memlock 8192B map_ids 3,5,11,9,8,10

btf_id 54

pids sysmon(807)The bytecode of an eBPF program is accessible as well, using the bpftool prog dump command.

int ProcCreateRawExit(struct bpf_our_raw_tracepoint_args * ctx):

0xffffffffc02f18e8:

; int ProcCreateRawExit(struct bpf_our_raw_tracepoint_args *ctx)

0: nopl 0x0(%rax,%rax,1)

5: xchg %ax,%ax

7: push %rbp

8: mov %rsp,%rbp

b: sub $0x98,%rsp

12: push %rbxAdditionally, the bpftool map list command will retrieve a complete list of maps. Again, there are unrelated results, but the PIDs describe associated processes.

11: array name eventStorageMap flags 0x0

key 4B value 65512B max_entries 512 memlock 33546240B

pids sysmon(807) The contents of a map can be accessed with bpftool map dump.

key:

00 00 00 00

value:

01 ff 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

ea 02 00 00 0c 56 00 00 85 88 52 b5 30 ee 3c 00

00 00 08 00 24 81 00 00 61 d7 37 66 00 00 00 00

ac 4e a8 08 00 00 00 00 61 d7 37 66 00 00 00 00

ac 4e a8 08 d7 8f ff ff 61 d7 37 66 00 00 00 00

ac 4e a8 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 20 00 00 00Retrieving the name and bytecode for each program should be enough to understand which functions an eBPF agent monitors. Outflank created a Bash script to expedite the enumeration described above.

Sensor Implementations – macOS

The EDR agents Outflank reviewed on macOS all had similar implementations. The following sections aim to describe commonalities as well as any unique approaches.

Authentication Events

Multiple agents collected authentication data using getutxent, some at regular intervals and others in response to specific events. For instance, one agent used the Darwin Notification API to subscribe to com.apple.system.utmpx events. Outflank created another Frida script that can be used with hook.py script to examine these subscriptions.

Other agents subscribed to the following ES API events as a trigger to check utmpx:

- AUTHENTICATION – The most general authentication event. Generated by normal login, sudo usage, and some remote logins.

- PTY_GRANT/CLOSE – Records each pseudoterminal control device (shell session), including local Terminal and remote SSH connections.

- LW_SESSION_LOGIN/LOGOUT – Occurs when a user logs in normally. Includes the username and a “graphical session ID” that appears to track whether a session has ended.

- OPENSSH_LOGIN/LOGOUT – SSH logins, including failed attempts. Includes the username and source address.

- LOGIN_LOGIN/LOGOUT – Official documentation states these events are generated for each “authenticated login event from

/usr/bin/login“. The author was unable to produce events of this type.

Process Events

All the reviewed macOS agents subscribed to the following process event types.

- EXEC

- FORK

- EXIT

File Events

All the reviewed macOS agents subscribed to the following file event types:

- CREATE

- OPEN

- CLOSE

- LINK

- UNLINK

- RENAME

- MOUNT

- CLONE

- SETMODE

- SETOWNER

- SETFLAGS

- SETEXTATTR

A subset of the agents subscribed to additional event types:

- UNMOUNT

- READDIR

- DELETEEXTATTR

- SETATTRLIST

- REMOUNT

- TRUNCATE

- SETACL – Although macOS uses POSIX file permissions, it also implements more granular access control using Access Control Lists (ACL).

Network Events

All the reviewed macOS agents used a network extension to implement a content filter provider. Refer to the previous sections for more information on the data available to content filters.

macOS-Specific Events

Each macOS agent was subscribed to a subset of the following OS-specific events:

- REMOTE_THREAD_CREATE

- PROC_SUSPEND_RESUME

- XP_MALWARE_DETECTED – XProtect, the built-in macOS antivirus, detected malware. A complimentary event type, XP_MALWARE_REMEDIATED, indicates that malware was removed.

- GET_TASK_READ/INSPECT/NAME – A process retrieved the task control/read/inspect/name port for another process. Mach ports are an IPC mechanism on macOS.

- CS_INVALIDATED – The code signing status for a process is now invalid, but that process is still running.

- SIGNAL – A process sent a signal to another process.

- UIPC_CONNECT – A process connected to a UNIX domain socket.

- BTM_LAUNCH_ITEM_ADD – A launch item was made known to background task management. This includes common macOS persistence methods like launch agents/daemons and login items.

Sensor Implementations – Linux

Unlike macOS agents, the Linux agents reviewed by Outflank had much greater diversity in their implementations. The following sections compare approaches taken by various products.

Authentication Events

A subset of the reviewed Linux agents hooked the following PAM functions:

pam_authenticate– Includes failed login attempts.pam_open_session– Likely required to correlate other events with a user session.

Other agents monitored specific files to capture authentication events:

/var/run/utmp/var/log/btmp– Includes failed login attempts.

Process Events

Each Linux agent used a tracepoint (some used raw tracepoints) for sched_process_exec. One product also placed a fentry probe on finalize_exec, an internal kernel function called by execve, but it was unclear what additional information this could provide. Only some agents appeared to monitor fork usage with a sched_process_fork tracepoint. All agents monitored process termination with tracepoints or fentry probes on sched_process_exit, taskstats_exit, sys_exit_setsid, or exit.

File Events

A subset of the reviewed Linux agents only monitored the following syscalls using fentry probes or kprobes:

chdirchmodchowncloneclone_file_rangecopy_file_rangedupfallocatefchdirfchmodfchmodatfchownfchownatopenatpwritereadrename

renameatrenameat2sendfilesetfsgidsetfsuidsetgidsetregidsetresgidsetreuidsetsidsetuidtruncateunlinkunlinkatunsharewrite

While some agents relied entirely on syscalls, others only traced a few and attached fentry probes or kprobes to the following internal kernel functions:

chmod_commonchown_commondo_filp_openioctl_file_clonelocks_remove_filemnt_want_writenotify_changesecurity_file_opensecurity_file_permissionsecurity_inode_getattrsecurity_inode_getxattrsecurity_inode_removexattrsecurity_inode_setxattrsecurity_inode_unlink

security_mmap_filesecurity_path_linksecurity_path_mkdirsecurity_path_renamesecurity_path_unlinksecurity_sb_freesecurity_sb_mountvfs_copy_file_rangevfs_fallocatevfs_linkvfs_renamevfs_unlinkvfs_write

Network Events

Outflank observed two general strategies for monitoring network traffic. Some agents monitored the following syscalls using kprobes or fentry probes:

socketbindacceptsetsockoptsocketcall

Instead of monitoring networking syscalls, the remaining agents traced the following internal kernel functions with fentry or kprobes:

sock_createinet_bind/inet6_bindinet_sendmsg/inet6_sendmsginet_recvmsg/inet6_recvmsginet_csk_acceptinet_acceptinet_listentcp_closeinet_releasetcp_v4_connect/tcp_v6_connectinet_dgram_connect– UDPinet_stream_connect– TCPsock_common_recvmsg– DCCPsk_attach_filter– Called whenSO_ATTACH_FILTERis passed to setsockopt.

Linux-Specific Events

Each Linux agent subscribed to a subset of the following OS-specific events.

security_bpf_map– Another program on the system can access or modify eBPF maps, but it usually requires theCAP_SYS_ADMINorCAP_BPFcapability. This means privileged users may be able to tamper with sensor data to silence or even spoof events. In response, some EDR agents monitor eBPF to protect their programs and maps.security_ptrace_access_check– Monitors ptrace attempts.security_netlink_send– Monitors netlink, an interface for sharing data between user-mode processes and the Linux kernel.madvise– The author suspects some agents hooked this syscall to detect the exploitation of vulnerabilities like Dirty COW.

Case Study: Spoofing Linux Syscalls

Diving into an application often inspires security researchers to discover logical flaws that lead to unintended yet desirable results. The example highlighted in this section still affects popular commercial products, and the author hopes to inspire additional community research in this space.

Phantom Attack

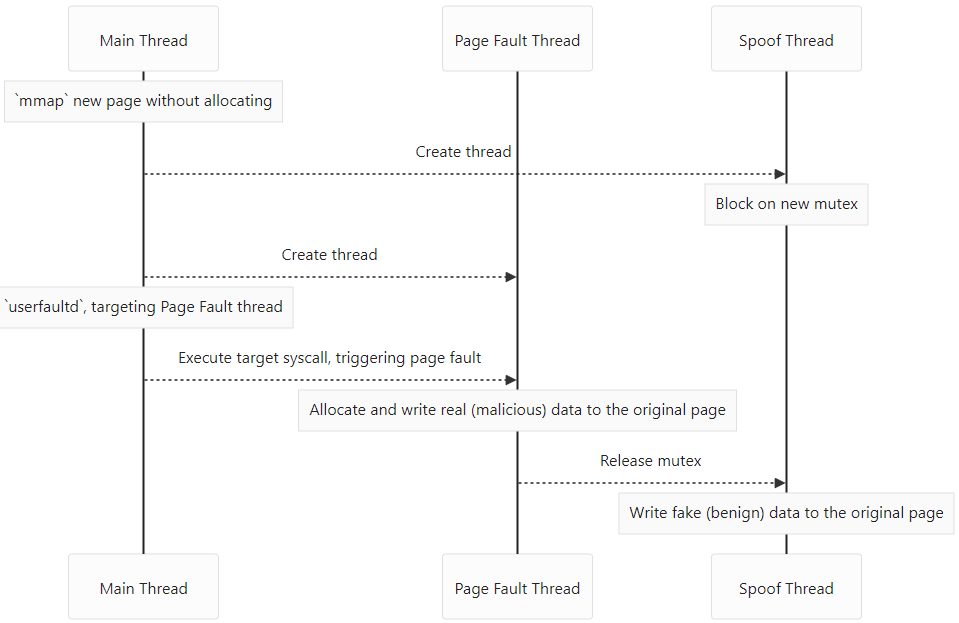

At DEF CON 29, Rex Guo and Junyuan Zeng exploited a TOCTOU vulnerability for Falco and Tracee. Their exploit for “Phantom Attack v1” demonstrates an ability to spoof specific fields in some network (connect) and file (openat) events. The attack requires three separate threads, as shown below.

A slight variation is required for the openat syscall, but it is conceptually similar. Ideally, the time-of-use (immediately after the page fault is handled) happens before benign data can be written to the original page. In practice, their POC was very reliable but required elevated privileges. According to its manual, userfaultfd requires the CAP_SYS_PTRACE capability since Linux 5.2. An alternative method of extending the TOCTOU window would be enough to exploit this vulnerability as a normal user.

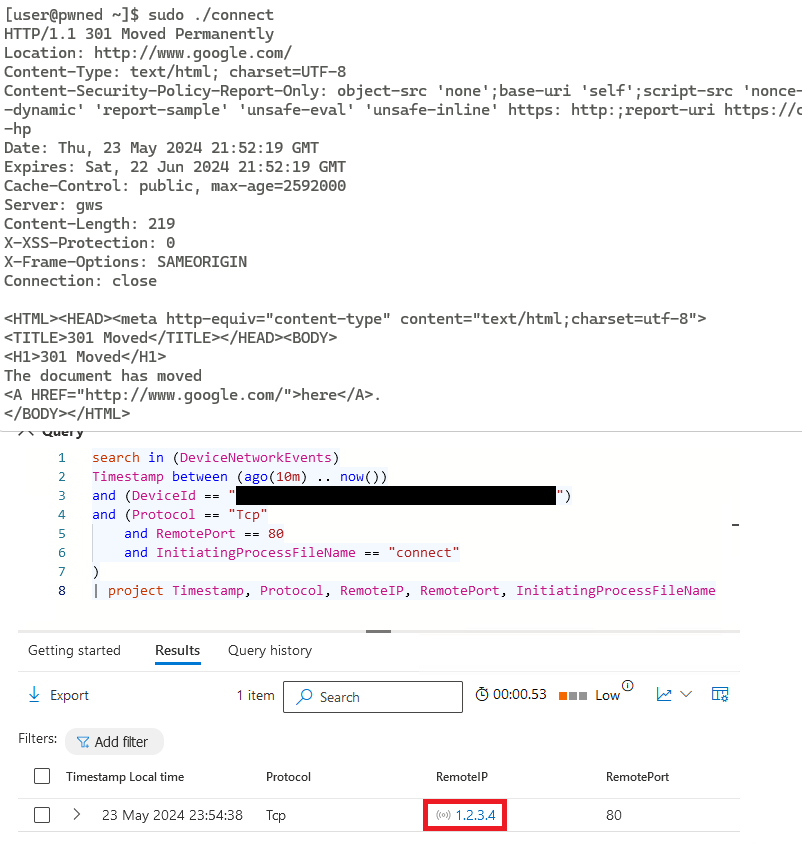

Falco and Tracee used kernel function tracing, but they were vulnerable to the attack because they traced system calls instead of internal kernel functions. Arguments provided by user-mode were evaluated directly, including pointers to memory allocated by the calling process. As described above, some EDR agents monitored networking with syscall kprobes, implying they are likely vulnerable to the same attack. Indeed, Outflank’s fork of the “Phantom Attack v1” POC for connect worked against multiple EDR products in testing. As demonstrated below, the original code was modified to make an HTTP GET request to the target (in this case, google.com) and output the response.

connectOutflank utilizes its knowledge of Windows, macOS, and Linux EDR to identify opportunities for evasion. In order to help other red teams easily implement these techniques and more, we’ve developed Outflank Security Tooling (OST), a broad set of evasive tools that allow users to safely and easily perform complex tasks. Consider scheduling an expert-led demo to learn more about the diverse offerings in OST.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh