2024-8-8 05:49:49 Author: hackernoon.com(查看原文) 阅读量:8 收藏

In this post, I'm going to show you how to provide more granular and more secure connectivity to and from a SaaS platform. The end result is a holistic solution that looks and feels like a natural extension of the SaaS platform and is either offered as a feature for enterprise-focused plans or as a competitive differentiator to all your customers. The total time required to run the demo is just a few minutes. I'll also dig deep into what's happening behind the scenes to explain how the magic works.

First, let me give some background on why this specific need arises and highlight the shortcomings in traditional implementations. Because those old approaches don't work anymore.

You need to start thinking of security as a feature. If you're a VP of engineering, if you're a product manager, product owner, give time to security, let your developers create a better, more secure infrastructure.

— Joel Spolsky, Founder of Stack Overflow

The most successful products over the coming decade will be the ones that realize the status-quo approaches are no longer good enough. You don't need to take Joel's word for it either; take a read of the details of the recently announced Private Cloud Compute from Apple. One of the most successful companies over the past two decades is making a clear statement that security, privacy, and trust will be a core differentiator.

They even discuss how current usage of protocols like TLS can't provide the end-to-end security and privacy guarantees customers should expect.

I worked on connecting systems to each other many years ago, a labor-intensive task in the earliest stages of my career. Our company was growing, and we'd patch the server room in the current building to the system we just installed in the new building. The new office was a few blocks down the street, and we were working with the local telco to install a dedicated line.

At the time, connecting two separate networks had an obvious and physically tangible reality to it.

We all moved on from those days. Now, modern tech stacks are more complicated; a series of interconnected apps spread across the globe, run in the cloud by 'best of breed' product companies. Over decades, we evolved. Today, it's rare that two separate companies actually want to connect their entire networks to each other—it's specific apps and workloads within each network that need to communicate.

Yet, we've continued to use old approaches as a way to "securely" connect our systems.

The actual running of cables has been abstracted away, but we're virtually doing the same thing. These old approaches expose you transitively to an uncountable number of networks, which is an enormous attack surface ripe for exploitation.

The Need to Connect to a Private System

What people mean when they say "cloud" or "on-prem" has become blurred over the previous decades. To avoid any confusion, I'll create a hypothetical scenario for us:

- Initech Platform: This is a SaaS platform that you operate. It's elastic and scaleable and hosted on one of the major cloud providers. Customers buy the platform to improve their DevOps processes as it provides visibility over a bunch of useful metrics and provides useful feedback directly into their development workflows.

- ACME Corp: This is a large customer of Initech that you want to support. They run a lot of infrastructure in various locations. Is it "on-prem" in the classic sense of being inside their own data center? Is it inside their own VPC on one of the major cloud providers? It doesn't matter! Customer systems are running in one or more networks that Initech doesn't control, that we don't have access to, and that aren't directly accessible from the public internet.

Proactive Engagement in Developer Workflows

In building the early version of the Initech Platform, there are a lot of potential customers to work with to prove product-market fit. It will integrate with the public APIs of the major version control system providers (for example, GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket, etc.), use the commit/webhooks to react to events, push results into the workflow, and everything works as expected.

This is great while the product is passive and simply reacts to events initiated by someone at ACME Corp. Many services want to provide value by assessing external changes in the world and being proactive in driving improvements for their customers.

Think of the many dependency or security scanning services—if there's a new vulnerability disclosure, they want to create a pull/merge request on all impacted repositories as quickly as possible. The fully managed VCS services with public APIs provide ways to enable this, however, the self-hosted versions of these products don't have a publicly accessible API.

The customers that opt to self-host these systems typically skew towards large enterprises, so now we're faced with some difficult decisions: Is Initech unable to sell their product to these high-value customers? Do customers have to buy a diminished version of the product that's missing one of the most valuable features? Or do we ask them to re-assess some aspect of their security & networking posture to give Initech access?

Access to Private Data

Initech needs to query a database to display its custom reporting solution. This isn't a problem that's unique to Initech as almost every Customer Data Platform (CDP) or visualization tool has the same problem: customers don't want to make their private data accessible from the public internet, so it will typically be in a database in a private subnet.

The Problems With Our Current Approaches

As I said earlier, modern tech stacks have evolved into a series of interconnected apps. However, the way we connect these apps has changed only a little from the way we connected networks decades ago. While these approaches are convenient and familiar, they were never designed for the use cases we have today.

They're instead attempting to make the smallest tweaks possible to the way things used to work to try and get close to how we need things to work today.

Putting Systems on the Public Internet

The default deployment option for most private systems is to locate them in a private network, with a private subnet, with no public IP addresses. There are very good reasons for this! The easiest option for Initech to connect to this private system would be to ask ACME Corp to provide a public IP address or hostname that could be accessible from the internet.

This is bad.

All of the good reasons for initially putting a system in a private network disconnected from the world immediately vanish. This system is now reachable by the entire public internet, allowing thousands of would-be hackers to constantly try and brute-force their way into the system or to simply DoS it. You're a single leaked credential, CVE, or other issue away from getting owned.

Reverse Proxies

Another approach is to put a reverse proxy in front of the system. I'm not just talking about something like nginx and HA Proxy; there's a whole category of hosted or managed services that fit this description too.

This has the advantage that ACME Corp is no longer putting a private system directly on the public internet. The reverse proxy also adds the ability to rate-limit or fine-tune access restrictions to mitigate potential DoS attacks. This is a defense in depth improvement, but ACME Corp is still allowing the entire public internet to reach and attempt to attack the proxy.

If it's compromised, it'll do what a proxy does: let traffic through to the intended destination.

IP Allow Lists

An incremental improvement is for Initech to provide a list of IPs they will be sending requests from and have ACME Corp manage their firewall and routing rules to allow requests only from those IP addresses. This isn't much of an improvement though.

At Initech, you won't want to have a tight coupling to your current app instances and the IP addresses; you'll want the flexibility to be able to scale infrastructure as required without the need to constantly inform customers of new IP addresses.

So, the IP addresses will most likely belong to a NAT gateway or proxy server. ACME Corp might assume that locking access down to only one or two source IP addresses means that only one or two remote machines have access to their network.

The reality is that anything on the remote network that can send a request through the NAT gateway or proxy will now be granted access to the ACME Corp network too. This isn't allowing a single app or machine in; you've permitted an entire remote network.

Even more concerning though is that IP source addresses are trivially spoofed. A potential attacker would be able to create a well-formed request, spoof the source address, and send data or instructions into the ACME Corp network. SaaS vendors, Initech included, also inevitably have to document the list of current IP addresses so there's a ready-made list of IPs to try and impersonate.

The more sophisticated your approach to IP filtering the more sophisticated an attacker needs to be to compromise it, but none of them are perfect. I've heard people claim in the past that IP spoofing is only really for DDoS attacks because in most cases, the attacker can't receive the response, and so they can't do anything useful.

Think about the systems we're connecting - how confident are you that there are zero fire-and-forget API calls that won't dutifully create/update/destroy valuable data? Good security is more than just preventing the exposure of data, it's also about protecting it and guaranteeing its integrity.

If you're a valuable target, such as a major financial institution, attackers have the motivation to use approaches like this to launch MitM attacks & intercept comms flows. If your customers and prospects and valuable targets, that makes you a valuable target too.

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)

VPNs are a common solution at many companies to allow employees to connect to the "corporate network" when they're outside of the office. They are also used to allow other systems to connect to an existing network.

The use case we're talking about here is different. It's about allowing two separate companies, a SaaS product and their customer(s), being able to communicate with each other.

In many of those cases, there's only one system at each end of the connection that should be able to talk to each other. Instead, we reach for a tool that is designed to connect entire networks. It's like running a virtual patch lead from the router in one company to the router in another.

If I asked you to do the physical version of that, to plug a cable from your production environment directly into the production environment of another company, you'd probably give it some pause. A lot of pause. And for good reason. But VPNs are "virtual" and "private" and so easy (relative to running a cable) and so ubiquitous we don't give it as much thought.

If all you needed to do was connect one thing in each network, you've used a very blunt instrument for what was meant to be a very precise task.

You can still do the precise task using a VPN, but there are layers of network-level controls and routing rules you need to ensure are in place to close down all the doors to just the one you want open in each network. It's another example of how we've got tools and approaches that are great at what they were designed for, but we're making incremental steps in how we use them to force them to work with our evolved needs.

Doing that securely means layering in more complexity and hoping that we get all of the detail in all of those layers right, all of the time. Getting it wrong carries risks of transitive access beyond the original intentions.

You Can't Trust the Network

What if I told you regardless of how much time, people, and money you invest in your security program, your network is almost certainly exposed to an easily exploitable security hole? …

industry data shows that less than 1% of the world's largest enterprises have yet to take any steps to protect their network from this new and emerging threat …

History has taught us that the right thing to do must be the easiest thing to do. This is particularly critical with software developers and protecting from intentionally malicious components. This slow adoption curve for security technology … effectively enabled bad actors to see the potential, innovate, and to drive the spectacular growth of cybercrime

— Mitchell Johnson, Sonatype

The problem with each of these approaches is that to assume it's secure requires many additional assumptions: that nobody on the internet will try to compromise you, that you can trust the source IP of the requests, that the remote network is solely composed of good actors, that these assumptions will continue to be true both now and indefinitely into the future… and that all of these assumptions are also true of every network you've connected to, and any network they've connected to, and any network…

Take a look at what this might look like from ACME Corp's perspective:

It's not just two networks and two companies now connected to each other; it's many networks. Each SaaS vendor will have their own set of services they use which multiplies this out further. Not only can you not trust the network, you can't trust anybody else's either. Any participant in this picture is only a network misconfiguration or compromised dependency away from transmitting that risk through the network(s).

And this picture is the most zoomed-in example of a fractal of this problem! Zoom out, and each vendor is connected to their own set of customers, with their own vendors, with their own customers... the risk surface area grows exponentially.

So, Let's Solve It!

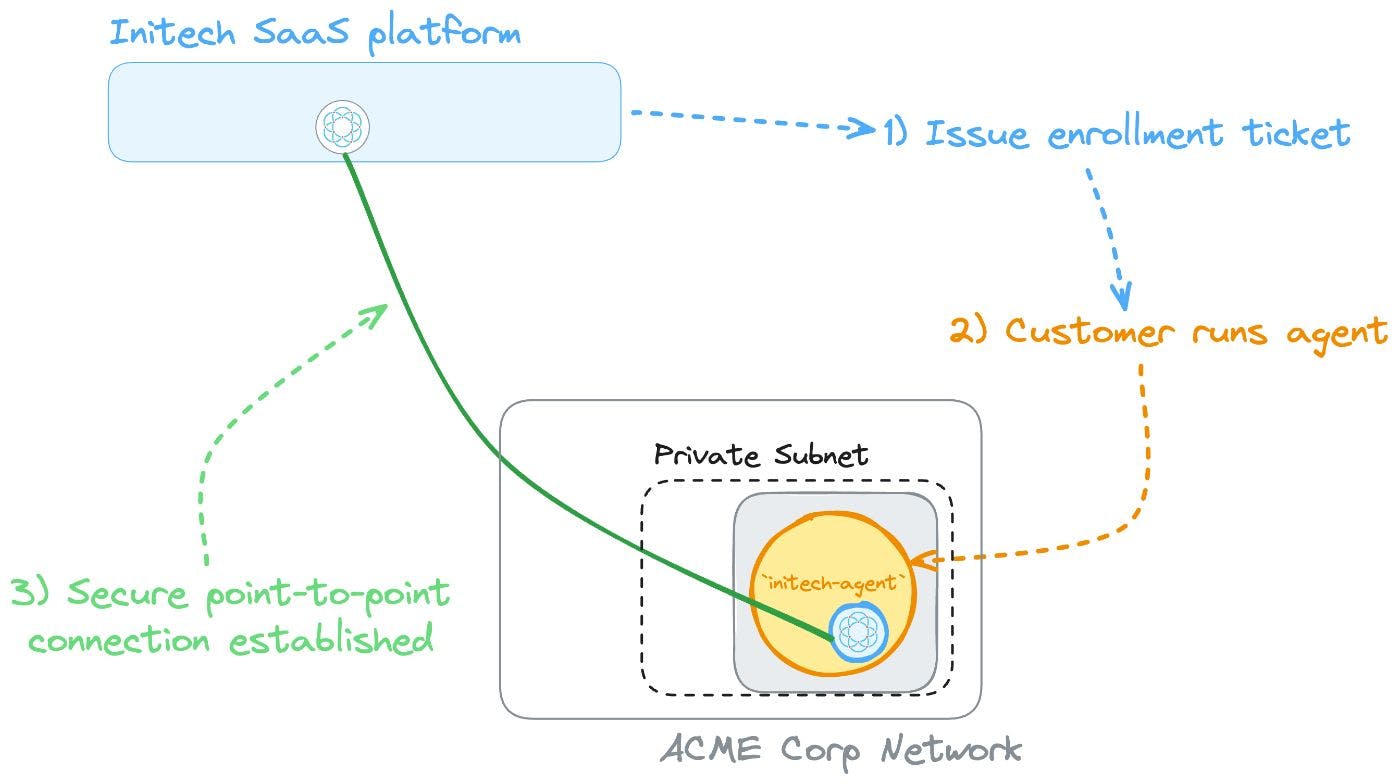

We can build security as a feature into our product within minutes! We'll raise the security bar by providing a more focused and granular solution. We're also going to stop pushing the problems onto customers like ACME Corp by asking them to make network-level changes.

Instead, we're going to shift secure connectivity up to an application-level concern and provide a holistic product experience by extending the Initech Platform into the specific places it needs to be.

The example here is going to walk through how Initech Platform can establish a connection to a self-hosted GitHub Enterprise server that's managed by ACME Corp. The final result will look like:

It only takes a few minutes to spin up all the required pieces! To learn how to do it, take a look at our code tour for building the basis of a self-hosted agent.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh