2024-10-23 19:0:48 Author: securelist.com(查看原文) 阅读量:3 收藏

Introduction

Lazarus APT and its BlueNoroff subgroup are a highly sophisticated and multifaceted Korean-speaking threat actor. We closely monitor their activities and quite often see them using their signature malware in their attacks — a full-feature backdoor called Manuscrypt. According to our research, Lazarus has been employing this malware since at least 2013 and we’ve documented its usage in 50+ unique campaigns targeting governments, diplomatic entities, financial institutions, military and defense contractors, cryptocurrency platforms, IT and telecommunication operators, gaming companies, media outlets, casinos, universities, and even security researchers — the list goes on.

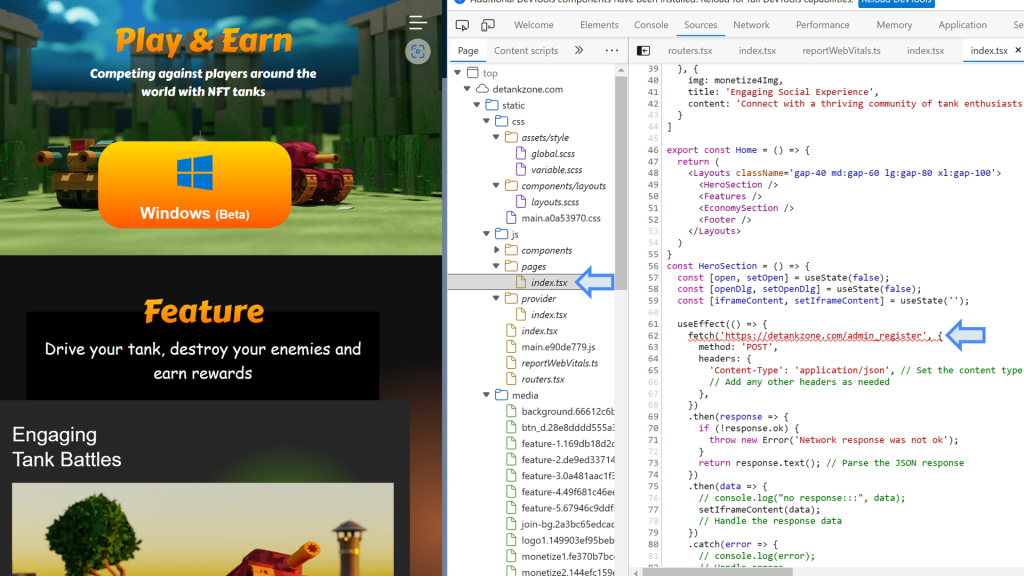

On May 13, 2024, our consumer-grade product Kaspersky Total Security detected a new Manuscrypt infection on the personal computer of a person living in Russia. Since Lazarus rarely attacks individuals, this piqued our interest and we decided to take a closer look. We discovered that prior to the detection of Manuscrypt, our technologies also detected exploitation of the Google Chrome web browser originating from the website detankzone[.]com. On the surface, this website resembled a professionally designed product page for a decentralized finance (DeFi) NFT-based (non-fungible token) multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) tank game, inviting users to download a trial version. But that was just a disguise. Under the hood, this website had a hidden script that ran in the user’s Google Chrome browser, launching a zero-day exploit and giving the attackers complete control over the victim’s PC. Visiting the website was all it took to get infected — the game was just a distraction.

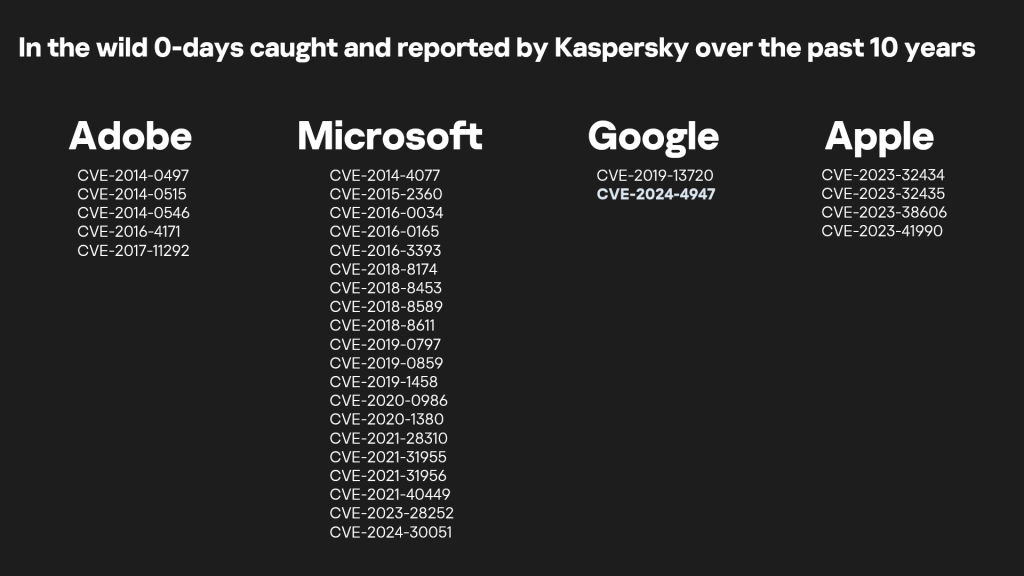

We were able to extract the first stage of the attack — an exploit that performs remote code execution in the Google Chrome process. After confirming that the exploit was based on a zero-day vulnerability targeting the latest version of Google Chrome, we reported our findings to Google the same day. Two days later, Google released an update and thanked us for discovering this attack.

Acknowledgement for finding CVE-2024-4947 (excerpt from the security fixes included into Chrome 125.0.6422.60)

Having notified Google about the discovered vulnerability, we followed responsible vulnerability disclosure policy and refrained from sharing specific details in public, giving users sufficient time to apply the patch. This approach is also intended to prevent further exploitation by threat actors. Google took additional steps by blocking detankzone[.]com and other websites linked to this campaign, ensuring that anyone attempting to access these sites — even without our products — would be warned of their malicious nature.

While we respected Google’s request for a set disclosure period, on May 28, 2024, Microsoft published a blog post titled “Moonstone Sleet emerges as new North Korean threat actor with new bag of tricks,” which partially revealed our findings. According to the blog, Microsoft had also been tracking the campaign and associated websites since February 2024. However, their analysis overlooked a key point in the malicious campaign: the presence of the browser exploit and the fact that it was a high-severity issue — a zero-day. In this report, we explore in great detail the vulnerabilities exploited by the attackers and the game they used as bait (spoiler alert: we had to develop our own server for this online game).

The exploit

The website used by the attackers as a cover for their campaign was developed in TypeScript/React, and one of its index.tsx files contained a small piece of code that loads and executes the Google Chrome exploit.

The exploit contains code for two vulnerabilities: the first is used to gain the ability to read and write Chrome process memory from the JavaScript, and the second is used to bypass the recently introduced V8 sandbox.

First vulnerability (CVE-2024-4947)

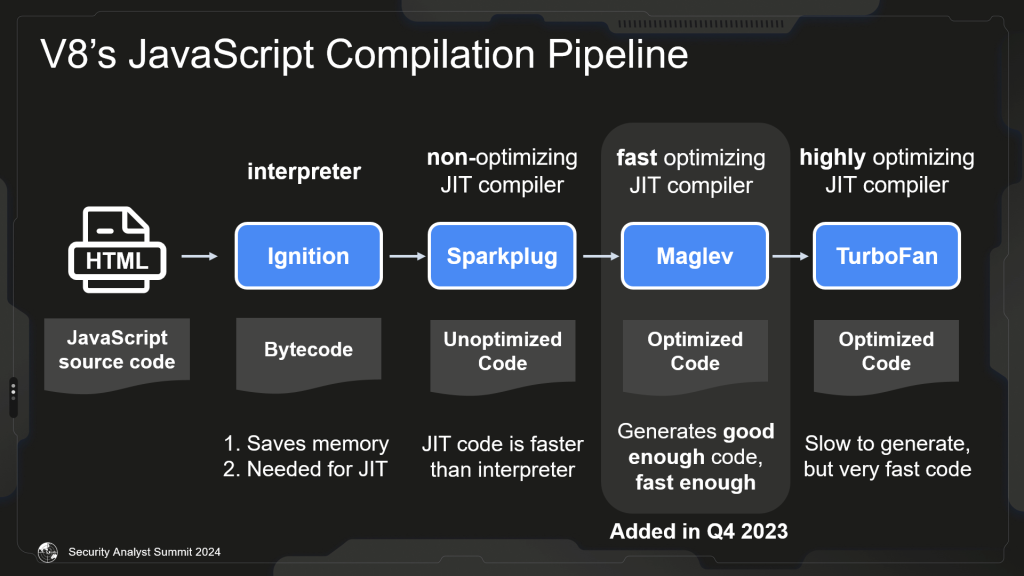

The heart of every web browser is its JavaScript engine. The JavaScript engine of Google Chrome is called V8 — Google’s own open-source JavaScript engine. For lower memory consumption and maximum speed, V8 uses a fairly complex JavaScript compilation pipeline, currently consisting of one interpreter and three JIT compilers.

When V8 starts to execute JavaScript, it first compiles the script into bytecode and executes it using the interpreter called Ignition. Ignition is a register-based machine with several hundred instructions. While executing bytecode, V8 monitors the program’s behavior, and may JIT-compile some functions for better performance. The best and fastest code is produced by TurboFan, a highly optimizing compiler with one drawback — the code generation takes too much time. Still, the difference in performance between Ignition and TurboFan was so significant that a new non-optimizing JIT compiler was introduced in 2021 called Sparkplug, which compiles bytecode into equivalent machine code almost instantly. Sparkplug-generated code runs faster than the interpreter, but the performance gap between Sparkplug- and TurboFan-generated code was still big. Because of this, in Chrome 117 (released in Q4 2023), the developers introduced a new optimizing compiler, Maglev, whose goal is to generate good enough code fast enough by performing optimizations based solely on feedback from the interpreter. CVE-2024-4947 (issue 340221135) is the vulnerability in this new compiler.

To understand this vulnerability and how it was exploited, let’s take a look at the code the attackers used to trigger it.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

import * as moduleImport from 'export var exportedVar = 23;'; function trigger() { moduleImport.exportedVar; const emptyArray = [1, 2]; emptyArray.pop(); emptyArray.pop(); const arrHolder = {xxarr: doubleArray, xxab: fakeArrayBuffer}; function f() { try { moduleImport.exportedVar = 3.79837e-312; } catch (e) { return false; } return true; } while (!f()) { } weakRef = new WeakRef(moduleImport); return {emptyArray, arrHolder}; } |

Code used by the attackers to trigger CVE-2024-4947

We can see in this code that it first accesses the exported variable exportedVar of the moduleImport module and then creates the emptyArray array and the arrHolder dictionary. However, it seems that no real work is done with them, they are just returned by the function trigger. And then something interesting happens – the f function is executed until it returns “true”. However, this function returns “true” only if it can set the exported variable moduleImport.exportedVar to the “3.79837e-312” value, and if an exception occurs because of this, the f function returns “false”. How could it be that executing the same expression moduleImport.exportedVar = 3.79837e-312; should always return “false” until it returns “true”?

LdaImmutableCurrentContextSlot [53] Star1 LdaConstant [0] SetNamedProperty r1, [1], [0] // moduleImport.exportedVar = 3.79837e-312; |

Bytecode produced by the Ignition interpreter for “moduleImport.exportedVar = 3.79837e-312;”

If we take a look at the bytecode produced for this expression by Ignition and at the code of the SetNamedProperty instruction handler, which is supposed to set this variable to the “3.79837e-312” value, we can see that it will always throw an exception — according to the ECMAScript specification, storing in a module object is always an error in JavaScript.

mov rax, 309000D616Dh // JS object ptr for "moduleImport" mov edi, [rax+3] add rdi, r14 mov rax, 309001870B5h // JS object ptr for "3.79837e-312" mov [rdi-1], eax |

JIT code produced by Maglev for “moduleImport.exportedVar = 3.79837e-312;”

But if we wait until this bytecode has been executed enough times and V8 decides to compile it using the Maglev compiler, we’ll see that the resulting machine code doesn’t throw an exception, but actually sets this property somewhere in the moduleImport object. This happens due to a missing check for storing to module exports — which is the CVE-2024-4947 vulnerability (you can find the fix here). How do attackers exploit it? To answer this, we need to understand how JavaScript objects are represented in memory.

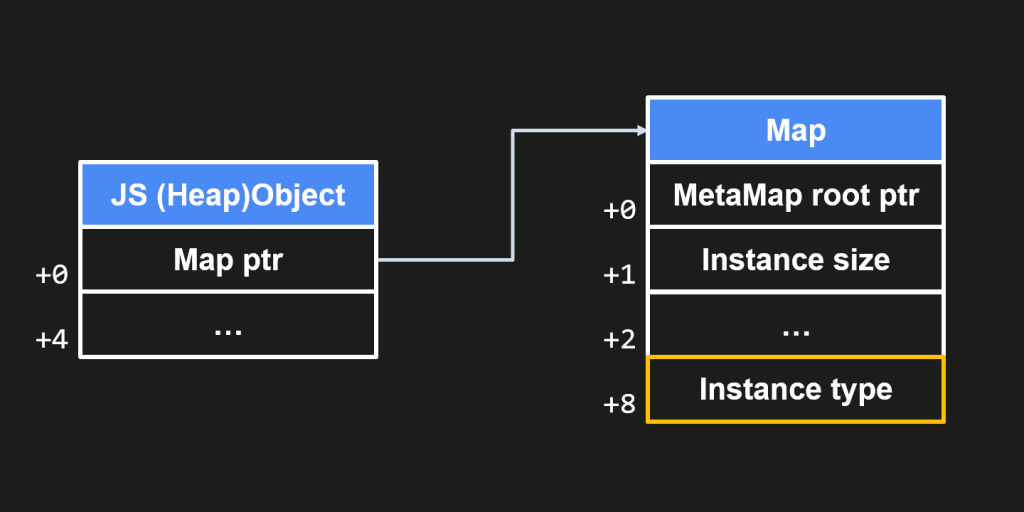

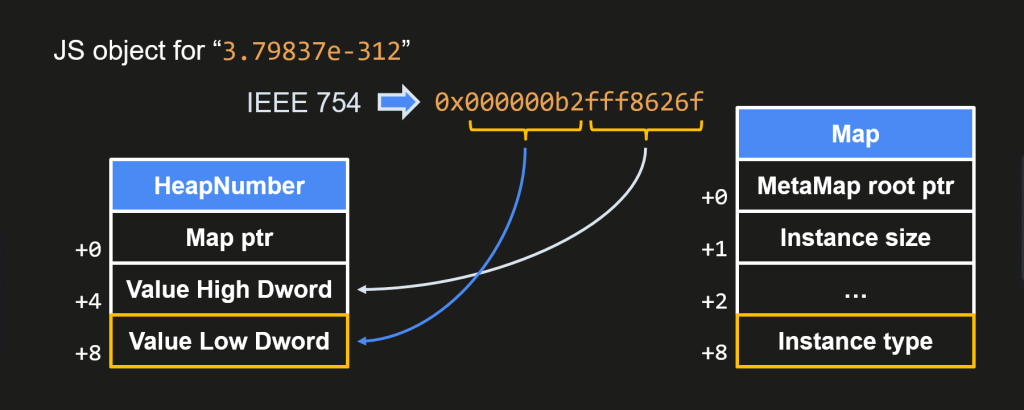

All JS objects begin with a pointer to a special object called Map (also known as HiddenClass) which stores meta information about the object and describes its structure. It contains the object’s type (stored at a +8 offset), number of properties, and so on.

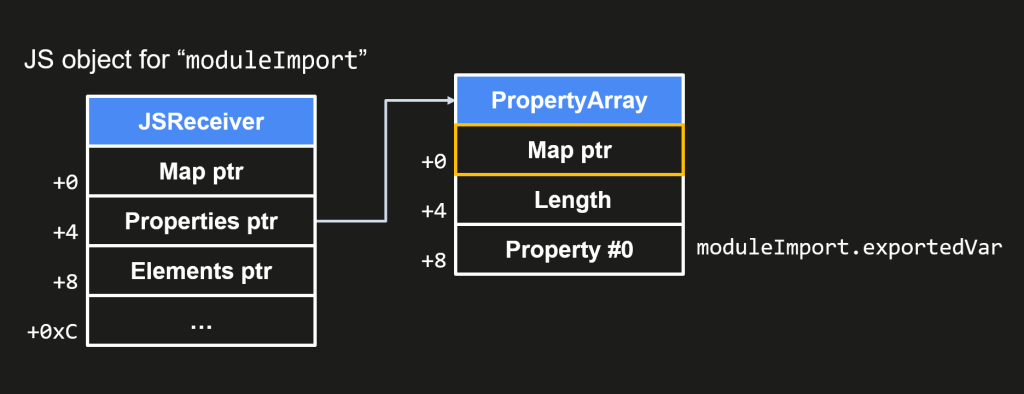

The moduleImport module is represented in memory as a JSReceiver object, which is the most generic JS object and is used for types for which properties can be defined. It includes a pointer to the array of properties ( PropertyArray) which is basically a regular JS object of the FixedArray type with its own Map. If in the expression moduleImport.exportedVar = 3.79837e-312; moduleImport was not a module but a regular object, the code would set the property #0 in that array, writing at a +8 offset; however, since it is a module and there is a bug, the code sets this property, writing at a +0 offset, overwriting the Map object with the provided object.

Since 3.79837e-312 is a floating-point number, it is converted to a 64-bit value (according to the IEEE 754 standard) and stored in a HeapNumber JS object at a +4 offset. This allows the attackers to set their own type for the PropertyArray object and cause a type confusion. Setting the type to 0xB2 causes V8 to treat the PropertyArray as a PropertyDictionary, which results in memory corruption because the PropertyArray and PropertyDictionary objects are of different sizes and the kLengthAndHashOffset field of the PropertyDictionary falls outside the bounds of the PropertyArray.

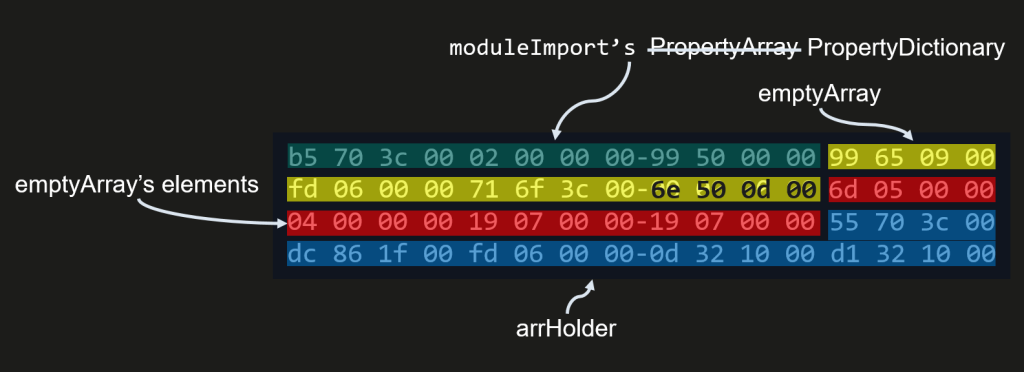

Now the attackers need to get the right memory layout and corrupt something useful. They defragment the heap and perform the actions that you can see in the trigger function.

What happens in this function is the following:

- It accesses the exported module variable moduleImport.exportedVar to allocate moduleImport’s PropertyArray.

- It creates an emptyArray with two elements.

- Removing elements from this array reallocates the object that is used for storing the elements and sets emptyArray’s length to 0. This is an important step because in order to overwrite emptyArray’s length with PropertyDictionary’s hash, the length/hash must be equal to 0.

- The trigger function creates the arrHolder dictionary with two objects. This step follows the creation of the emptyArray to allow the pointers of these two objects to be accessed and overwritten when the length of emptyArray is corrupted. The first object, xxarr: doubleArray is used to construct a primitive for getting the addresses of JS objects. The second object, xxab: fakeArrayBuffer is used to construct a primitive for getting read/write access to the whole address space of the Chrome process.

- Next, the trigger function executes the f function until it is compiled by Maglev, and overwrites the type of the PropertyArray so it is treated as a PropertyDictionary object.

- Executing new WeakRef(moduleImport) triggers the calculation of PropertyDictionary’s hash, and the length of emptyArray is overwritten with the hash value.

- The trigger function returns emptyArray and arrHolder containing objects that can be overwritten with emptyArray.

After this, the exploit again abuses Maglev, or rather the fact that it optimizes the code based on the feedback collected by the interpreter. The exploit uses Maglev to compile a function that loads a double value from an array obtained using arrHolder.xxarr. When this function is compiled, the attackers can overwrite the pointer to an array obtained using arrHolder.xxarr via emptyArray[5] and use this function to get the addresses of JS objects. Similarly, the attackers use arrHolder.xxab to compile a function that sets specific properties and overwrites the length of another ArrayBuffer-type object along with the pointer to its data (backing_store_ptr). This becomes possible when the pointer to the object accessible via arrHolder.xxab is replaced via emptyArray[6] with a pointer to the ArrayBuffer. This gives the attackers read and write access to the entire address space of the Chrome process.

Second vulnerability (V8 sandbox bypass)

At this point, the attackers can read and write memory from JavaScript, but they need an additional vulnerability to bypass the newly introduced V8 (heap) sandbox. This sandbox is purely software-based and its main function is to isolate the V8 memory (heap) in such a way that attackers cannot access other parts of the memory and execute code. How does it do this? You may have noticed that all the pointers in the previous section are 32 bits long. This is not because we’re talking about a 32-bit process. It’s a 64-bit process, but the pointers are 32 bits long because V8 uses something called pointer compression. The pointers are not stored in full, but just as their lower parts, or they could also be seen as a 32-bit offset from some “base” address. The upper part (the “base” address) is stored in CPU registers and added by the code. In this case, attackers should not be able to obtain real pointers from the isolated memory and have no way to obtain addresses for the stack and JIT-code pages.

To bypass the V8 sandbox, the attackers used an interesting but very common vulnerability associated with interpreters — we have previously seen variations of this vulnerability in multiple virtual machine implementations. In V8, regular expressions are implemented using its own interpreter, Irregexp, with its own set of opcodes. The Irregexp VM is completely different from Ignition, but it is also a register-based VM.

RegisterT& operator[](size_t index) { return registers_[index]; } BYTECODE(PUSH_REGISTER) { ADVANCE(PUSH_REGISTER); if (!backtrack_stack.push(registers[LoadPacked24Unsigned(insn)])) { return MaybeThrowStackOverflow(isolate, call_origin); } DISPATCH(); } BYTECODE(SET_REGISTER) { ADVANCE(SET_REGISTER); registers[LoadPacked24Unsigned(insn)] = Load32Aligned(pc + 4); DISPATCH(); } |

Examples of vulnerable code in Irregexp VM instruction handlers

The vulnerability is that the virtual machine has a fixed number of registers and a dedicated array for storing them, but the register indexes are decoded from the instruction bodies and are not checked. This allows attackers to access the memory outside the bounds of the register array.

PUSH_REGISTER r(REGISTERS_COUNT + idx) POP_REGISTER r(0) PUSH_REGISTER r(REGISTERS_COUNT + idx + 1) POP_REGISTER r(1) // Overwrite "output_registers" ptr SET_REGISTER r(REGISTERS_COUNT), holderAddressLow SET_REGISTER r(REGISTERS_COUNT + 1), holderAddressHigh // Overwrite "output_register_count" SET_REGISTER r(REGISTERS_COUNT + 2), 2 // MemCopy(output_registers_, registers_.data(), output_register_count_ * sizeof(RegisterT)); SUCCEED |

Malicious Irregexp VM bytecode for reading the memory outside of the register array bounds

Coincidentally, the pointers to output_registers and output_register_count are located right next to the register array. This allows the attackers to read and write the memory outside of the V8 sandbox with the help of the SUCCEED opcode. Attackers use this to overwrite JIT’ed code with shellcode and execute it.

This issue (330404819) was submitted and fixed in March 2024. It is unknown whether it was a bug collision and the attackers discovered it first and initially exploited it as a 0-day vulnerability, or if it was initially exploited as a 1-day vulnerability.

Shellcode

At this point, the attackers need additional vulnerabilities to escape the Chrome process and gain full access to the system. In the best practices of sophisticated attackers, they run a validator in the form of a shellcode that collects as much information as possible and sends it to the server to decide whether to provide the next stage (another exploit) or not. This decision is made based on the following information: CPUID information (vendor, processor name, etc), whether it’s running on a VM or not, OS version and build, number of processors, tick count, OS product type, whether it’s being debugged or not, process path, file version info of system modules, file version info of process executable, and SMBIOS firmware table.

By the time we analyzed the attack, the attackers had already removed the exploit from the decoy website, preventing us from easily obtaining the next stage of the attack. At Kaspersky, we possess technologies that have allowed us to discover and help to fix a huge number of 0-day privilege escalation vulnerabilities exploited by sophisticated attackers in various malware campaigns over the years; however, in this particular case we would have to wait for the next attack in order to extract its next stage. We’ve decided to not wait, preferring to let Google fix the initial exploit used to perform the remote code execution in Google Chrome.

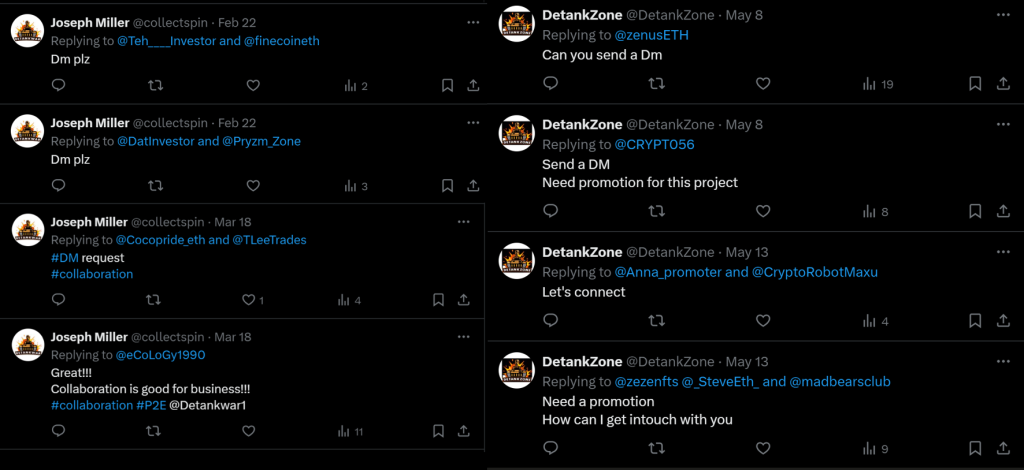

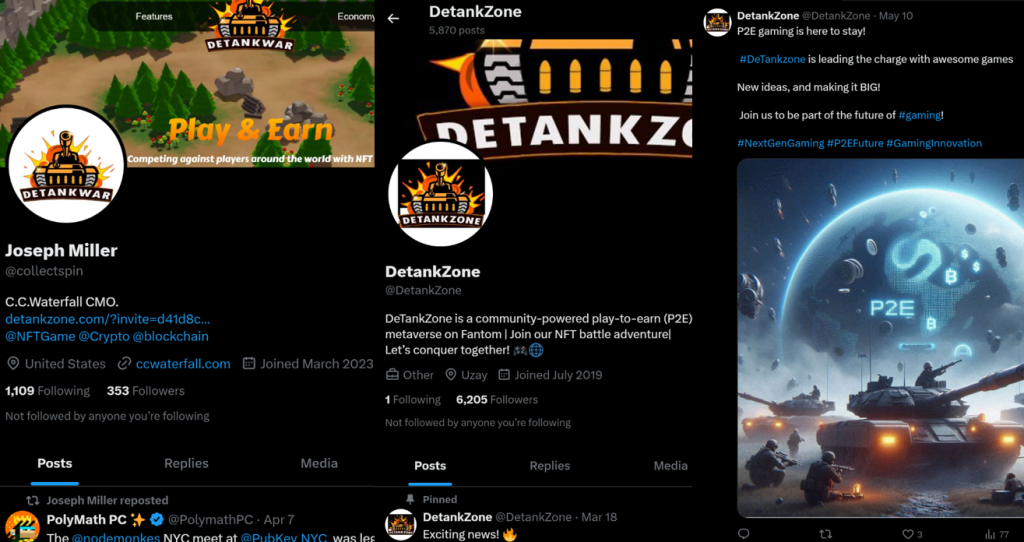

What never ceases to impress us is how much effort Lazarus APT puts into their social engineering campaigns. For several months, the attackers were building their social media presence, regularly making posts on X (formerly Twitter) from multiple accounts and promoting their game with content produced by generative AI and graphic designers.

One of the tactics used by the attackers was to contact influential figures in the cryptocurrency space to get them to promote their malicious website and most likely to also compromise them.

The attackers’ activity was not limited to X — they also used professionally designed websites with additional malware, premium accounts on LinkedIn, and spear phishing through email.

The game

What particularly caught our attention in this attack was that the malicious website attacking its visitors using a Google Chrome zero-day was inviting them to download and try a beta version of a computer game. As big computer games fans ourselves, we immediately wanted to try it. Could the attackers have developed a real game for this campaign? Could this be the first computer game ever developed by a threat actor? We downloaded detankzone.zip and it looked legit: the 400 MB-archive contained a valid file structure of a game developed in Unity. We unpacked the game’s resources and found “DeTankZone” logos, HUD elements, and 3D model textures. Debugging artifacts indicated that the game had been compiled by the attackers. We decided to give it a spin.

After an intro with the game’s logo, we are greeted with a typical online gaming start menu, asking us to enter valid account credentials to access the game. We tried to log in using some common account names and passwords, and then tried to register our own account through the game and the website — but nothing worked.

Is that really all this game has to offer? We started reverse engineering the game’s code and discovered that there was more content available beyond this start menu. We found the code responsible for communication with the game server and started reverse engineering that as well. The game was hardcoded to use the server running at “api.detankzone[.]com,” which clearly wasn’t working. But we really wanted to check this game out! What to do? We decided to develop our own game server, of course.

First, we discovered that the game uses the Socket.IO protocol to communicate with the server, so we chose the python-socketio library to develop our own server. We then found a function with a list of all supported command names (event names) and reverse engineered how they are obfuscated. After that, we reverse engineered how the data was encoded: it turned out to be a JSON encrypted with AES256 and encoded with Base64. For the AES key it uses the string “Full Stack IT Service 198703Game”, while the string “MatGoGameProject” is used for the IV. We hoped that this information might reveal the identities of the game’s developers, but a Google search yielded no results. Finally, we reverse engineered the data format for a couple of commands, implemented them on our server, and replaced the server URL with the address of our own server. Success! After all this we were able to log into the game and play with the bots!

Yes, it turned out to be a real game! We played it for a bit and it was fun — it reminded us of some shareware games from the early 2000s. Definitely worth the effort. The textures look a little tacky and the game itself closely resembles a popular Unity tutorial, but if Lazarus had developed this game themselves, it would have set a new bar for attack preparation. But no — Lazarus stayed true to themselves. It turns out that the source code for this game was stolen from its original developers.

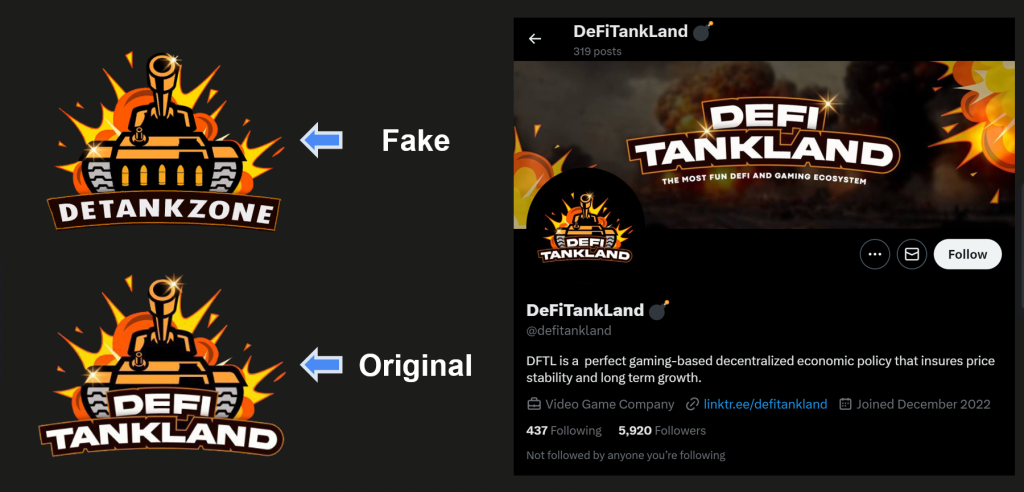

The original game

We found a legitimate game that served as a prototype for the attacker’s version – it’s called DeFiTankLand (DFTL). Studying the developers’ Telegram chat helped us build a timeline of the attack. On February 20, 2024, the attackers began their campaign, advertising their game on X. Two weeks later, on March 2, 2024, the price of the DeFiTankLand’s currency, DFTL2 coin, dropped, and the game’s developers announced on their Telegram that their cold wallet had been hacked and $20,000 worth of DFTL2 coins had been stolen. The developers blamed an insider for this. Insider or not, we suspect that this was the work of Lazarus, and that before stealing the coins they first stole the game’s source code, modified all the logos and references to DeFiTankLand, and used it to make their campaign more credible.

Conclusions

Lazarus is one of the most active and sophisticated APT actors, and financial gain remains one of their top motivations. Over the years, we have uncovered many of their attacks on the cryptocurrency industry, and one thing is certain: these attacks are not going away. The attackers’ tactics are evolving and they’re constantly coming up with new, complex social engineering schemes. Lazarus has already successfully started using generative AI, and we predict that they will come up with even more elaborate attacks using it. What makes Lazarus’s attacks particularly dangerous is their frequent use of zero-day exploits. Simply clicking a link on a social network or in an email can lead to the complete compromise of a personal computer or corporate network.

Historically, half of the bugs discovered or exploited in Google Chrome and other web browsers have affected its compilers. Huge changes in the code base of the web browser and the introduction of new JIT compilers inevitably lead to a large number of new vulnerabilities. What can end users do about this? While Google Chrome continues to add new JIT compilers, there is also Microsoft Edge, which can run without JIT at all. But it’s also fair to say that the newly introduced V8 sandbox might be very successful at stopping bugs exploitation in compilers. Once it becomes more mature, exploiting Google Chrome with JIT may be as difficult as exploiting Microsoft Edge without it.

Indicators of Compromise

Exploit

B2DC7AEC2C6D2FFA28219AC288E4750C

E5DA4AB6366C5690DFD1BB386C7FE0C78F6ED54F

7353AB9670133468081305BD442F7691CF2F2C1136F09D9508400546C417833A

Game

8312E556C4EEC999204368D69BA91BF4

7F28AD5EE9966410B15CA85B7FACB70088A17C5F

59A37D7D2BF4CFFE31407EDD286A811D9600B68FE757829E30DA4394AB65A4CC

Domains

detankzone[.]com

ccwaterfall[.]com

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh