2024-10-10 00:9:14 Author: www.horizon3.ai(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

On July 10, 2024, Palo Alto released a security advisory for CVE-2024-5910, a vulnerability which allowed attackers to remotely reset the Expedition application admin credentials. While we had never heard of Expedition application before, it’s advertised as:

The purpose of this tool is to help reduce the time and efforts of migrating a configuration from a supported vendor to Palo Alto Networks. By using Expedition, everyone can convert a configuration from Checkpoint, Cisco, or any other vendor to a PAN-OS and give you more time to improve the results.

Further reading the documentation, it became clear that this application might have more attacker value than initially expected. The Expedition application is deployed on Ubuntu server, interacted with via a web service, and users remotely integrate vendor devices by adding each system’s credentials.

This blog details finding CVE-2024-5910, but also how we ended up discovering 3 additional vulnerabilities which we reported to Palo Alto:

- CVE-2024-9464: Authenticated Command Injection

- CVE-2024-9465: Unauthenticated SQL Injection

- CVE-2024-9466: Cleartext Credentials in Logs

CVE-2024-5910: No Reversing Needed

Given the description of the vulnerability, it sounded like there existed some built in function that allowed reseting the admin credential.

Missing authentication for a critical function in Palo Alto Networks Expedition can lead to an Expedition admin account takeover for attackers with network access to Expedition.

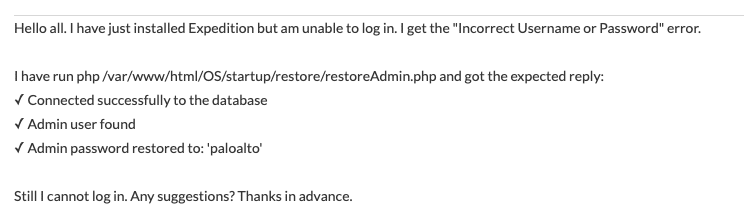

Googling “palo alto expedition reset admin password”, yielded this forum post as a top result.

Immediately, I see that this PHP file the user is executing locally is hosted in the folder /var/www/html/, which seems interesting! After several hours and failing three times to deploy the Expedition application on an old supported Ubuntu 20.04 server, we finally get the application deployed to test. We find that a simple request to the that exact endpoint over the web service resets the admin password.

Give an Inch, Take a Mile

While we now have administrative access the Expedition application, this does not allow us to read all the stored credentials across the system. We turned our attention to trying to turn this admin access into remote code execution on the server.

The Expedition web server is hosted via the Apache2 web service where, as we saw earlier, the /var/www/html directory is used as the web root. A significant amount of files are served via the web root, many seemingly unnecessarily, and are exposed via the web services. The Expedition web service utilizes php as the majority of its code base. Narrowing down the attack surface to files of interest, we look for php files that include the word “exec” – which if left unchecked may be an avenue for command injection.

We happen upon the file /var/www/html/bin/CronJobs.php, because it contains both a call to ‘exec’ and takes user input from the passed request parameters. Any valid session ID for any role user will allow a user to interact with this endpoint.

The call to exec appears on line 332 when the user updates an existing cronjob, and constructs the command to execute from data stored within the local MySQL database for the corresponding cronjob entry. Importantly, the cronjob entry for the passed cron_id must exist in the cronjobs database table.

Inspecting how these database entries are created, we find that also within CronJobs.php that there is a create cronjob function. When the request parameters specify the action is add, it will create an empty cronjob entry in the database.

We have now populated the cronjob table with a cronjob entry.

With a valid cronjob entry in the database, now we must find a way to insert a malicious command so that it can be retrieved and executed by the call to exec we found earlier. Looking back at the update or action = set operation where the call to exec occurs, we find that the command value is constructed in several ways depending on the passed request parameters.

Looking at line 278, when the recurrence is Daily, the command is constructed using 3 variables, 2 of which are user controlled. The cron_id looks like a good candidate to attempt to inject a command, but careful inspection of the SQL statement used to insert the malicious command into the database requires a valid cron_id to insert with.

Turning our attention to the other variable, time_today, we see it is constructed by taking the request parameter start_time and splitting it on the semicolon character. But never validating that the time is a valid time.

We craft our request so that the start_time[0] becomes a malicious command to be executed.

start_time=\"; touch /tmp/hacked ; :

And the final curl request looks like the following:

curl -ik ‘https://10.0.40.64/bin/CronJobs.php’ -H ‘Cookie: PHPSESSID=rpagjtqkqkf5269be9ro5597r7’ -d “action=set&type=cron_jobs&project=pandb&name=test&recurrence=Daily&start_time=\”; touch /tmp/hacked ; :&cron_id=1″

This vulnerability was assigned CVE-2024-9466. Our proof of concept can be found here.

Post-Exploitation

Once you have access to the server as the www-data user from the above vulnerability, pilfering credentials out of the database is straight forward.

To dump all API keys and cleartext credentials execute the following SQL query:

mysql -u root -p'paloalto' pandbRBAC -e 'SELECT hostname,key_name,api_key,user_name,user_password FROM device_keys dk, devices d WHERE dk.device_id=d.id'

While looking through the system for any other credentials, we happened upon a file called /home/userSpace/devices/debug.txt. This world-readable file contained the raw request logs of the Expedition server when it exchanged cleartext credentials for API keys in the device integration process. The Expedition server only stores the API keys, and is not supposed to retain the cleartext credentials, but this log file showed all the credentials used in cleartext. This issue was reported and assigned CVE-2024-9466.

Unauthenticated SQL Injection to Credential Pilfering

We still had a feeling more vulnerabilities lurked in the application, and went back to analyzing the multitude of files exposed in the web root. Narrowing down the attack surface to files of interest, we look for PHP files that include the word “GET”, but do not include the Authentication.php or sessionControl.php authentication logic – which may indicate an unauthenticated endpoint which takes request parameters as input.

We happen upon the file /var/www/html/bin/configurations/parsers/Checkpoint/CHECKPOINT.php. This file is reachable unauthenticated, takes HTTP request parameters as inputs, and then constructs SQL queries with that input.

Looking for a path to SQL injection, we first find that when the action=import, other request parameters we control are parsed to create the variables routeName and id and used in a string format to construct a query on line 73.

Unfortunately, the table that is being selected in the query does not exist by default – so queries will fail even if we can construct a malicious query. Fortunately, the code path when action=get has logic that will create this table in the given database.

An unauthenticated curl request like the below will create the policies_to_import_Checkpoint table in the pandbRBAC database.

curl -ivk 'https://10.0.40.64/bin/configurations/parsers/Checkpoint/CHECKPOINT.php' -d "action=get&type=existing_ruleBases&project=pandbRBAC"

Returning to the logic when action=import, we now can construct a curl request which won’t immediately fail. The most simple version of SQL injection as an example with an unauthenticated curl request:

curl -ivk 'https://10.0.40.64/bin/configurations/parsers/Checkpoint/CHECKPOINT.php' -d "action=import&type=test&project=pandb&signatureid=1 OR 1=1"

Will cause the query to hit the database like so:

Given we have unauthenticated SQL injection, tables of interest to leak data via blind SLEEP based payloads are the “users” and “devices” tables which contain password hashes and device API keys like demonstrated in the previous post-exploitation section.

Firing up the SQLMAP tool, and supplying it the endpoint and parameter to inject and table to dump, it successfully dumps the entire users table.

python3 sqlmap.py -u "https://10.0.40.64/bin/configurations/parsers/Checkpoint/CHECKPOINT.php?action=im port&type=test&project=pandbRBAC&signatureid=1" -p signatureid -T users --dump

This vulnerability was assigned CVE-2024-9465. Our proof of concept can be found here.

Indicators of Compromise

The file /var/apache/log/access.log will log HTTP requests and should be inspected for the endpoints abused in these vulnerabilities.

/OS/startup/restore/restoreAdmin.php– Reset admin credentials/bin/Auth.php– Authenticate with reset admin credentials/bin/CronJobs.php– Insert malicious SQL data for command injection/bin/configurations/parsers/Checkpoint/CHECKPOINT.php– Unauthenticated SQL injection to exfiltrate database data

Exposure

At the time of writing, there are approximately 23 Expedition servers exposed to the internet, which makes sense given it doesn’t seem to be an application that would need to be exposed given its function.

Disclosure Timeline

11 July 2024 – Reported authenticated command injection to Palo Alto PSIRT

12 July 2024 – Reported unauthenticated SQL injection to Palo Alto PSIRT

12 July 2024 – Palo Alto acknowledges receipt of both issues

28 July 2024 – Reported cleartext credentials in logs to Palo Alto PSIRT

1 August 2024 – Palo Alto acknowledges receipt of issue

9 October 2024 – Palo Alto Advisory for CVE-2024-9464, CVE-2024-9465, CVE-2024-9466 released

9 October 2024 – This blog post

NodeZero

Horizon3.ai clients and free-trial users alike can run a NodeZero operation to determine the exposure and exploitability of this issue.

Sign up for a free trial and quickly verify you’re not exploitable.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh