Targeted attacks

MATA: Lazarus’s multi-platform targeted malware framework

The more sophisticated threat actors are continually developing their TTPs (Tactics, Techniques and Procedures) and the toolsets they use to compromise the systems of their targets. However, malicious toolsets used to target multiple platforms are rare, because they required significant investment to develop and maintain them. In July, we reported the use of an advanced, multi-purpose malware framework developed by the Lazarus group.

We discovered the first artefacts relating to this framework, dubbed ‘MATA’ (the authors named their infrastructure ‘MataNet’) in April 2018. Since then, Lazarus has further developed MATA; and there are now versions for Windows, Linux and macOS operating systems.

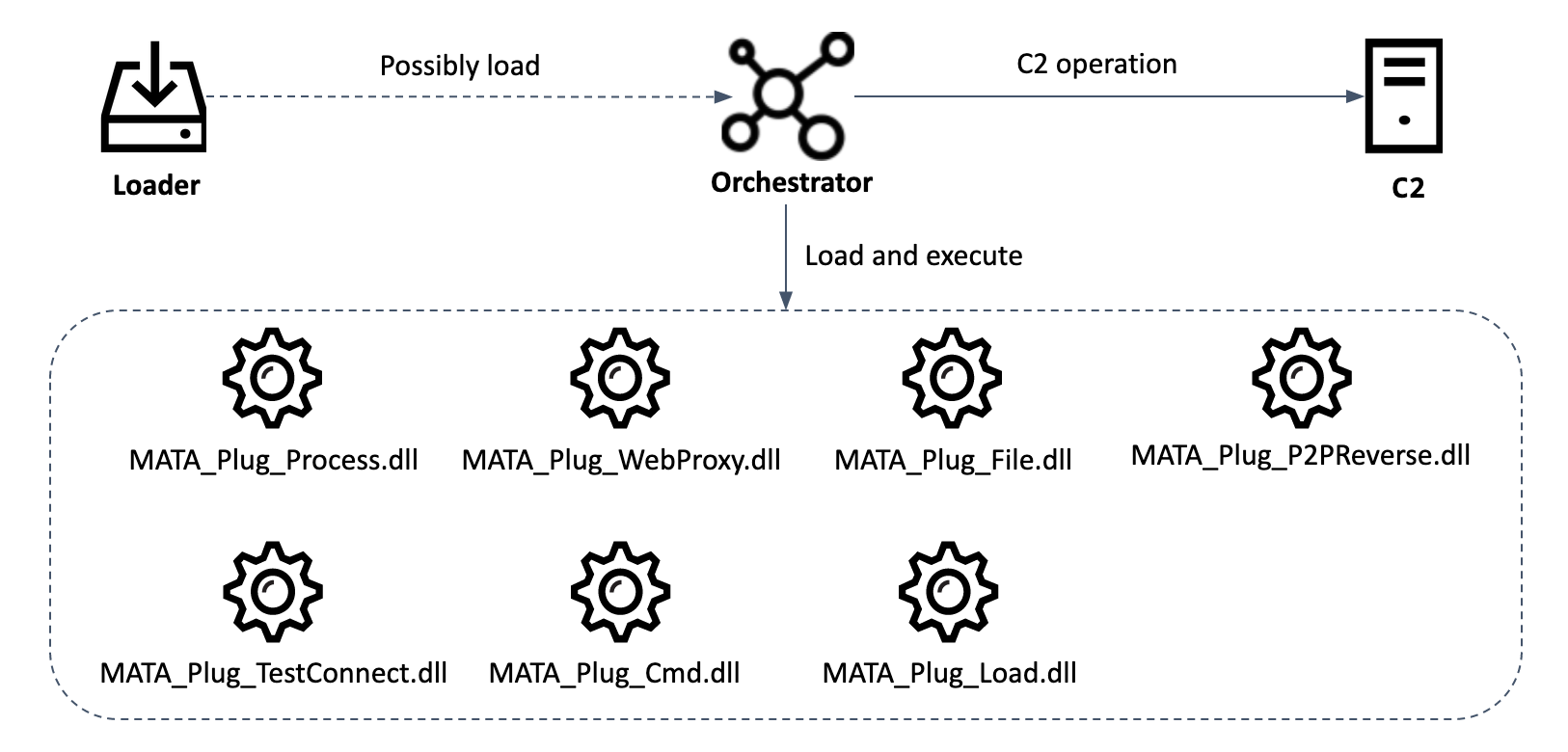

The MATA framework consists of several components, including a loader, an orchestrator (which manages and coordinates the processes once a device is infected) a C&C server and various plugins.

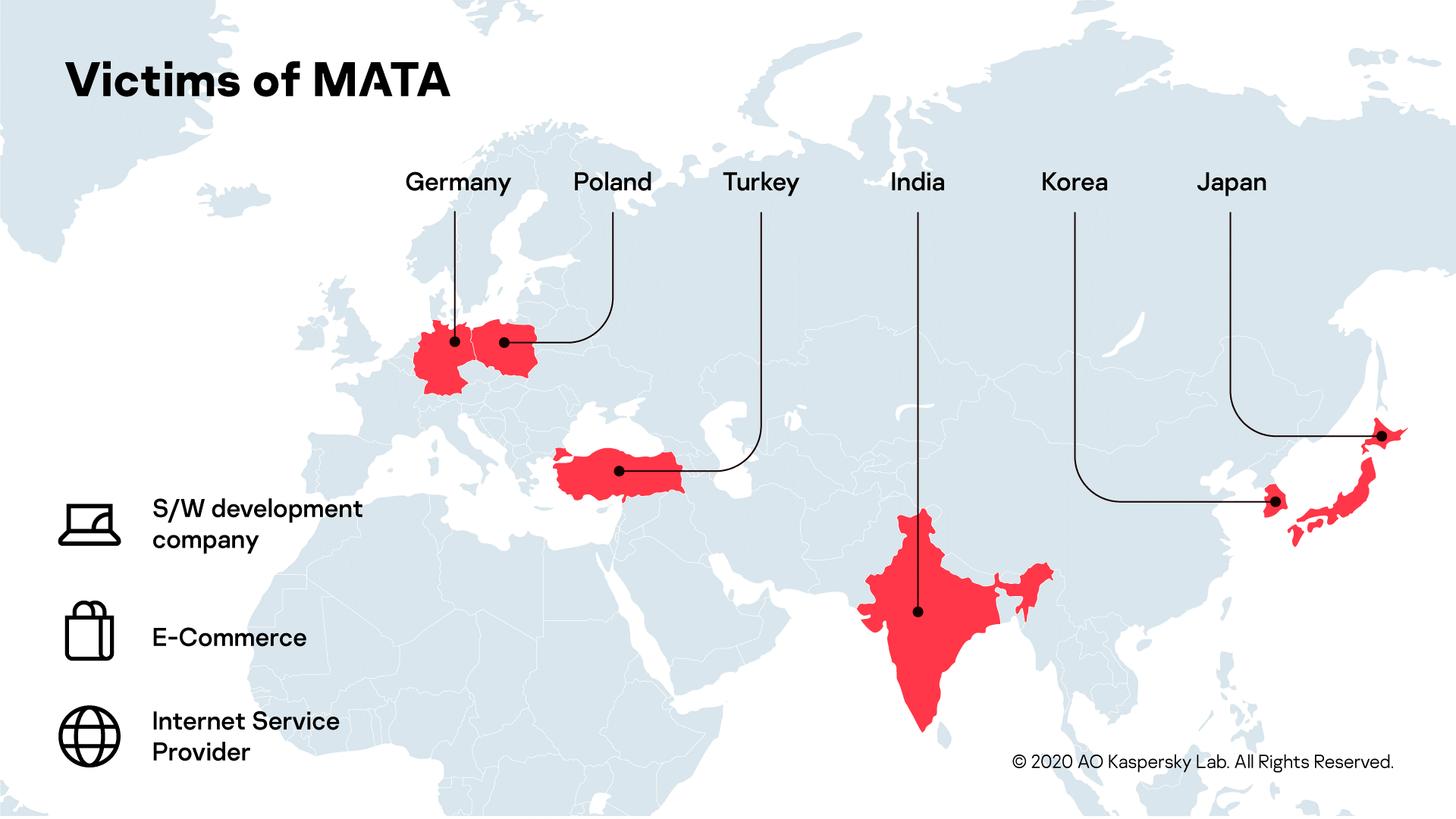

Lazarus has used MATA to infiltrate the networks of organizations around the world and steal data from customer databases; and, in at least one case, the group has used it to spread ransomware – you can read more about this in the next section. The victims have included software developers, Internet providers and e-commerce sites; and we detected traces of the group’s activities in Poland, Germany, Turkey, Korea, Japan, and India.

You can read more about MATA here.

Lazarus on the hunt for big game

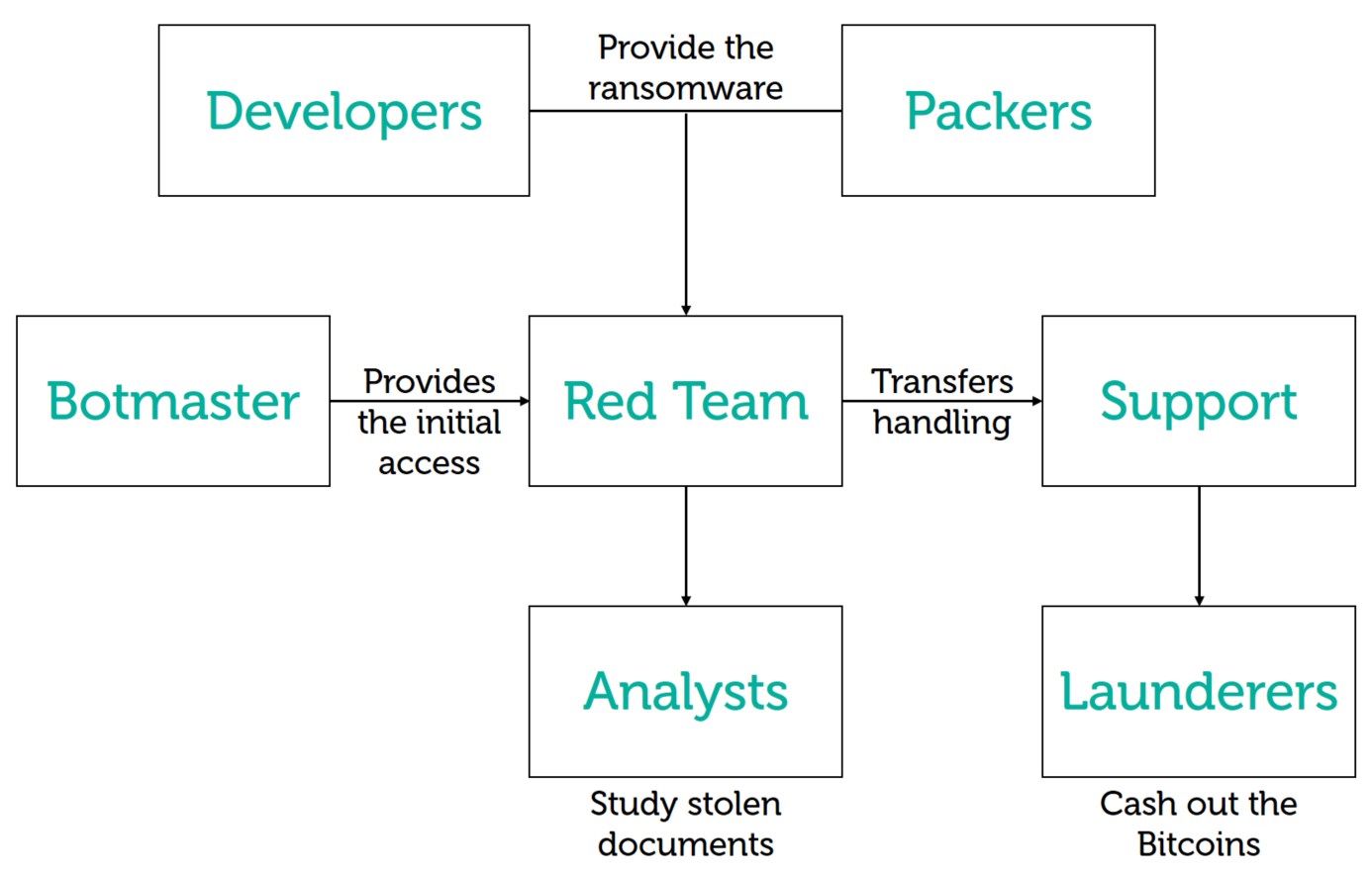

Targeted ransomware has been on the increase in recent years. Typically, such attacks are carried out by criminal groups, who license ‘as-a-service’ ransomware from third-party malware developers and then distribute it by piggy-backing established botnets.

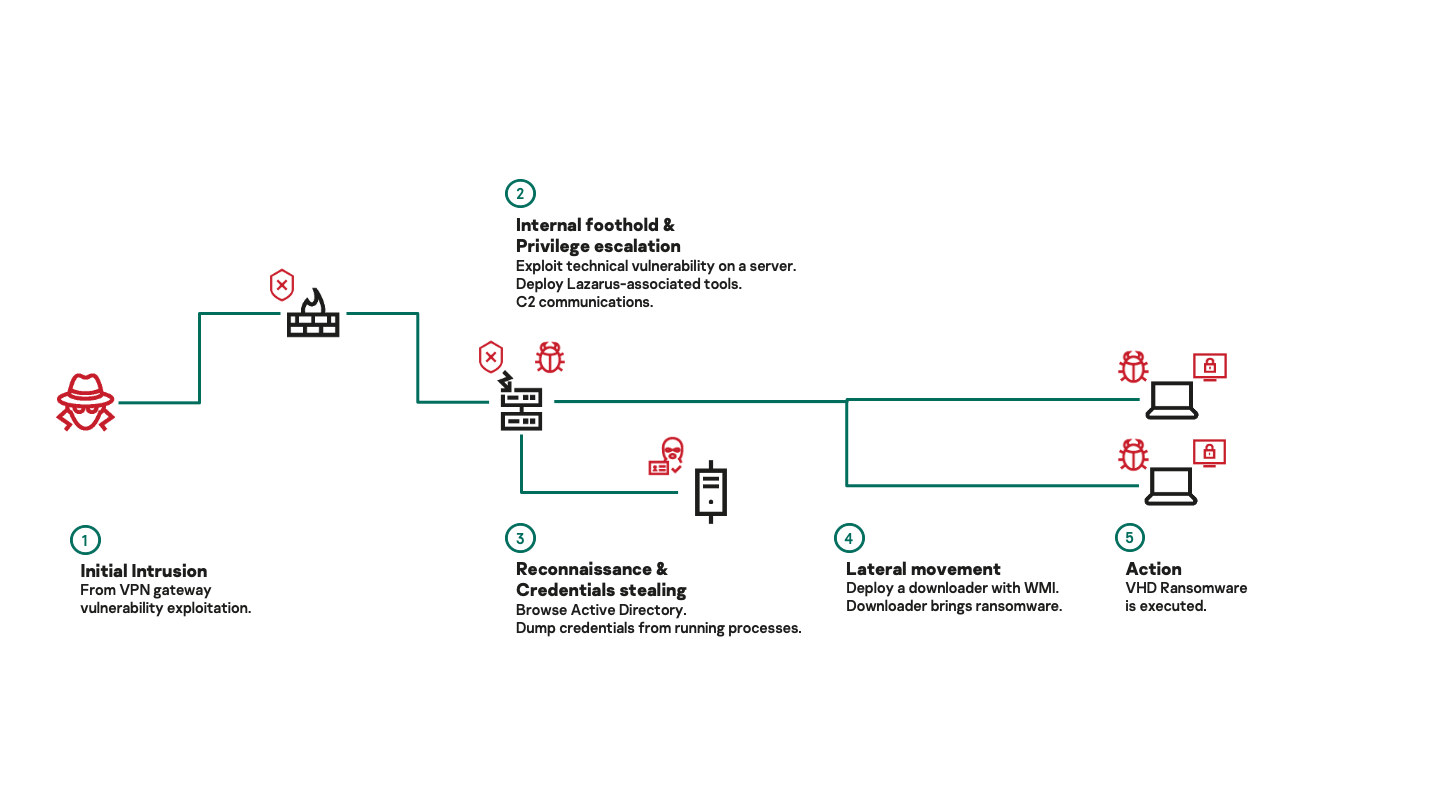

However, earlier this year we discovered a new ransomware family linked to the Lazarus APT group. The VHD ransomware operates much like other ransomware – it encrypts files on drives connected to the victim’s computer and deletes System Volume Information (used as part of the Windows restore point feature) to prevent recovery of data. The malware also suspends processes that could potentially lock important files, such as Microsoft Exchange or SQL Server. However, the delivery mechanism is more reminiscent of APT campaigns. The spreading utility contains a list of administrative credentials and IP addresses specific to the victim, which is uses to brute-force the SMB service on every discovered computer. Whenever it makes a successful connection, a network share is mounted and the VHD ransomware is copied and executed through WMI calls.

While investigating a second incident, we were able to uncover the full infection chain. The malware gained access to a victim’s system by exploiting a vulnerable VPN gateway and then obtained administrative rights on the compromised machines. It used these to install a backdoor and take control of the Active Directory server. Then all computers were infected with the VHD ransomware using a loader created specifically for this task.

Further analysis revealed the backdoor to be part of the MATA framework described above.

WastedLocker

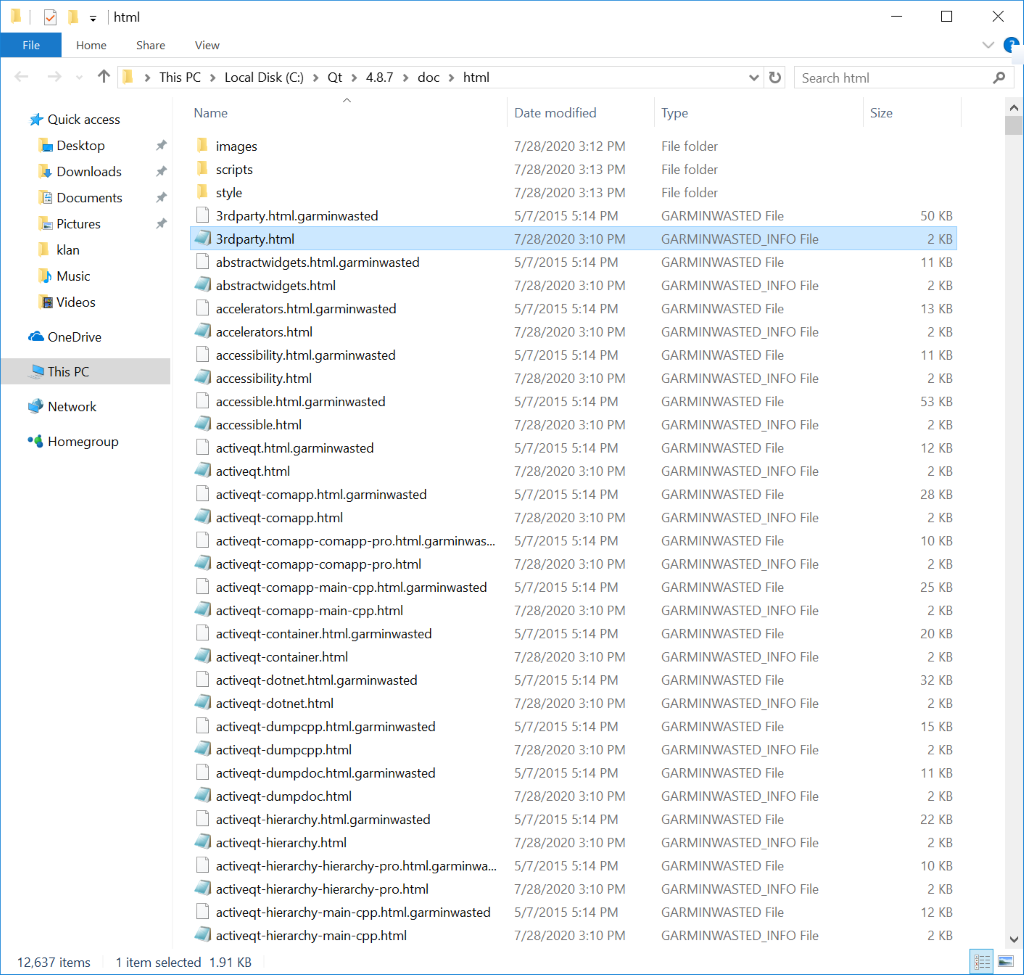

Garmin, the GPS and aviation specialist, was the victim of a cyber-attack in July that resulted in the encryption of some of its systems. The malware used in the attack was the WastedLocker and you can read our technical analysis of this ransomware here.

This ransomware, the use of which has increased this year, has several noteworthy features. It includes a command line interface that attackers can use to control the way it operates – specifying directories to target and setting a priority of which files to encrypt first; and controlling the encryption of files on specified network resources. WastedLocker also features a bypass for UAC (User Account Control) on Windows computers that allows the malware to silently elevate its privileges using a known bypass technique.

WastedLocker uses a combination of AES and RSA algorithms to encrypt files, which is a standard for ransomware families. Files are encrypted using a single public RSA key. This would be a weakness if this ransomware were to be distributed in mass attacks, since a decryptor from one victim would have to contain the only private RSA key that could be used to decrypt the files of all victims. However, since WastedLocker is used in attacks targeted at a specific organization, this decryption approach is worthless in real-world scenarios. Encrypted files are given the extension garminwasted_info, he added – and unusually, a new info file is created for each of the victim’s encrypted files.

CactusPete’s updated Bisonal backdoor

CactusPete is a Chinese-speaking APT threat actor that has been active since 2013. The group has typically targeted military, diplomatic and infrastructure victims in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the U.S. However, more recently the group has shifted its focus more towards other Asian and Eastern European organizations.

This group, which we would characterize as having medium level technical capabilities, seems to have acquired greater support and has access to more complex code such as ShadowPad, which CactusPete deployed earlier this year against government, defence, energy, mining and telecoms organizations.

Nevertheless, the group continues to use less sophisticated tools. We recently reported the group’s use of a new variant of the Bisonal backdoor to steal information, execute code on target computers and perform lateral movement within the network. Our research began with a single sample, but using the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE) we discovered more than 300 almost identical samples. All of these appeared between March 2019 and April this year – so the group has developed more than 20 samples per month! Bisonal is not advanced, relying instead on social engineering in the form of spear-phishing e-mails.

Operation PowerFall

Earlier this year our technologies prevented an attack on a South Korean company. Our investigation uncovered two zero-day vulnerabilities: a remote code execution exploit for Internet Explorer and an elevation of privilege exploit for Windows. The exploits targeted the latest builds of Windows 10 and our tests demonstrated reliable exploitation of Internet Explorer 11 and Windows 10 build 18363 x64.

The exploits operated in tandem. The victim was first targeted with a malicious script that, because of the vulnerability, was able to run in Internet Explorer. Then a flaw in the system service further escalated the privileges of the malicious process. As a result, the attackers were able to move laterally across the target network.

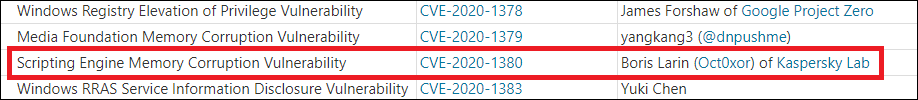

We reported our discoveries to Microsoft, who confirmed the vulnerabilities. At the time of our report, the security team at Microsoft had already prepared a patch for the elevation of privilege vulnerability (CVE-2020-0986): although, before our discovery, Microsoft hadn’t considered exploitation of this vulnerability to be likely. The patch for this vulnerability was released on 9 June. The patch for the remote code vulnerability (CVE-2020-1380) was released on 11 August.

We named this malicious campaign Operation PowerFall. While we have been unable to find a clear link to known threat actors, we believe that DarkHotel might be behind it. You can read more about it here and here.

The latest activities of Transparent Tribe

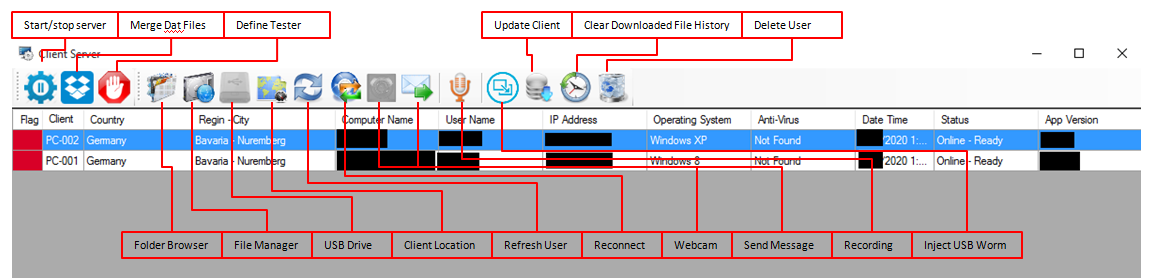

Transparent Tribe, a prolific threat actor that has been active since at least 2013, specializes in cyber-espionage. The group’s main malware is a custom .NET Remote Access Trojan (RAT) called Crimson RAT, spread by means of spear-phishing e-mails containing malicious Microsoft Office documents.

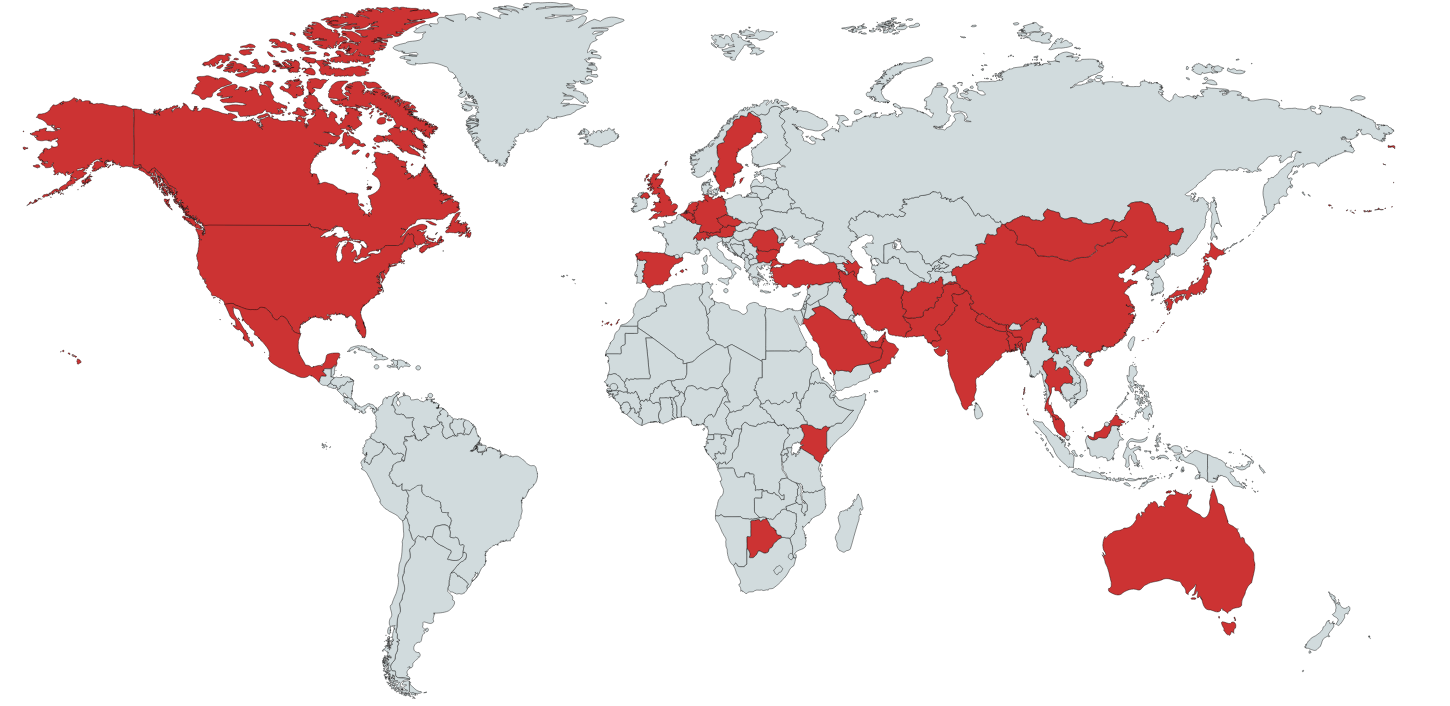

During our investigation into the activities of Transparent Tribe, we found around 200 Crimson RAT samples. Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) telemetry indicates that there were more than a thousand victims in the year following June 2019. The main targets were diplomatic and military organizations in India and Pakistan.

Crimson RAT includes a range of functions for harvesting data from infected computers. The latest additions include a server-side component used to manage infected client machines and a USB worm component developed for stealing files from removable drives, spreading across systems by infecting removable media and downloading and executing a thin-client version of Crimson RAT from a remote server.

We also discovered a new Android implant used by Transparent Tribe to spy on mobile devices. The threat actor used social engineering to distribute the malware, disguised as a fake porn video player and a fake version of the Aarogya Setu COVID-19 tracking app developed by the government of India.

The app is a modified version of the AhMyth Android RAT, open source malware, downloadable from GitHub and built by binding a malicious payload inside legitimate apps. The malware is designed to collect information from the victim’s device and send it to the attackers.

DeathStalker: mercenary cybercrime group

In August, we reported the activities of a cybercrime group that specializes in stealing trade secrets – mainly from fintech companies, law firms, and financial advisors, although we’ve also seen an attack on a diplomatic entity. The choice of targets suggests that this group, which we have named DeathStalker, is either looking for specific information to sell, or is a mercenary group offering an ‘attack on demand’ service. The group has been active since at least 2018; but it’s possible that the group’s activities could go back further, to 2012, and may be linked to the Janicab and Evilnum malware families.

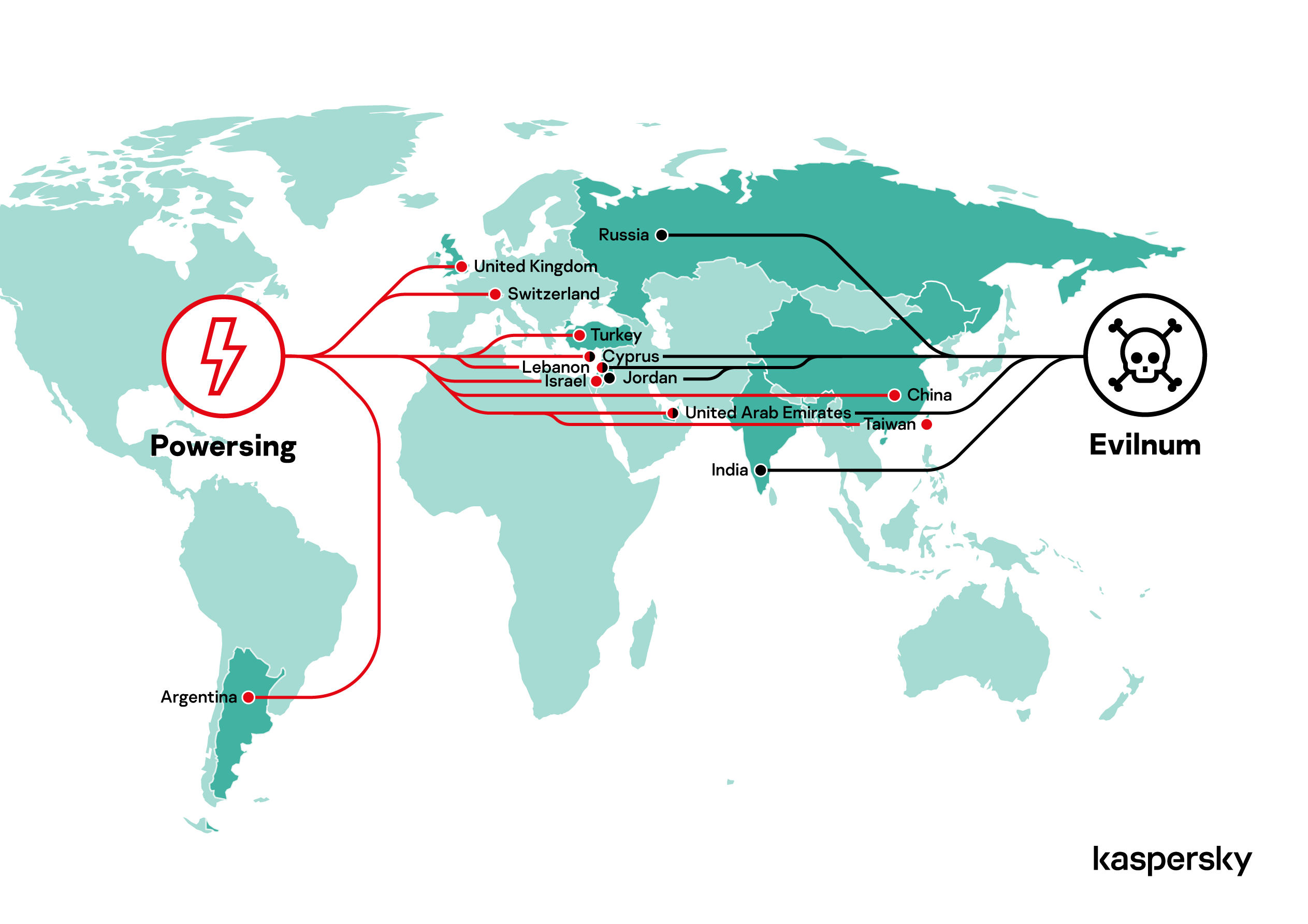

We have seen Powersing-related activities in Argentina, China, Cyprus, Israel, Lebanon, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, the UK and the UAE. We also located Evilnum victims in Cyprus, India, Lebanon, Russia, Jordan and the UAE.

The group’s use of a PowerShell implant called Powersing first brought DeathStalker to our attention. The operation starts with spear-phishing e-mails with attached archives containing a malicious LNK file. If the victim clicks on the archive, it starts a convoluted sequence resulting in the execution of arbitrary code on the computer

Powersing periodically takes screenshots on the victim’s computer and sends them to the C2 (Command and Control) server. It also executes additional PowerShell scripts that are downloaded from the C2 server. So Powersing is designed to provide the attackers with an initial point of presence on the infected computer from which to install additional malware.

DeathStalker camouflages communication between infected computers and the C2 server by using public services as dead drop resolvers: these services allow the attackers to store data at a fixed URL through public posts, comments, user profiles, content descriptions, etc.

DeathStalker offers a good example of what small groups or even skilled individuals can achieve, without the need for innovative tricks or sophisticated methods. DeathStalker should serve as a baseline of what organizations in the private sector should be able to defend against, since groups of this sort represent the type of cyber-threat companies today are most likely to face. We advise defenders to pay close attention to any process creation related to native Windows interpreters for scripting languages, such as powershell.exe and cscript.exe: wherever possible, these utilities should be made unavailable. Security awareness training and security product assessments should also include infection chains based on LNK files.

You can read more about DeathStalkers here.

Other malware

The Tetrade: Brazilian banking malware goes global

Brazil has a well-established criminal underground and local malware developers have created many banking Trojans over the years. Typically, this malware is used to target customers of local banks. However, Brazilian cybercriminals are starting to expand their attacks and operations abroad, targeting other countries and banks. The Tetrade is our designation for four large banking Trojan families that have been created, developed and spread by Brazilian criminals, but which are now being used at a global level. The four malware families are Guildma, Javali, Melcoz and Grandoreiro.

We have seen attempts to do this before, with limited success using very basic Trojans. The situation is now different. Brazilian banking Trojans have evolved greatly, with hackers adopting techniques for bypassing detection, creating highly modular and obfuscated malware and using a very complex execution flow – making analysis more difficult. Notwithstanding the banking industry’s adoption of technologies aimed at protecting customers, including the deployment of plugins, tokens, e-tokens, two-factor authentication, CHIP and PIN credit, fraud continues to increase because Brazil still lacks proper cybercrime legislation.

Brazilian criminals are benefiting from the fact that many banks operating in Brazil also have operations elsewhere in Latin America and in Europe, making it easy to extend their attacks to customers of these financial institutions. They are also rapidly creating an ecosystem of affiliates, recruiting cybercriminals to work with in other countries, adopting MaaS (Malware-as-a-Service) and quickly adding new techniques to their malware as a way to keep it relevant and financially attractive to their partners.

The banking Trojan families are seeking to innovate by using DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm), encrypted payloads, process hollowing, DLL hijacking, a lot of LoLBins, fileless infections and other tricks to obstruct analysis and detection. We believe that these threats will evolve to target more banks in more countries.

We recommend that financial institutions monitor these threats closely, while improving their authentication processes, boosting anti-fraud technology and threat intelligence data to understand and mitigate such risks. Further information on these threats, along with IoCs, YARA rules and hashes, are available to customers of our Financial Threat Intelligence services.

The dangers of streaming

Home entertainment is changing as the adoption of streaming TV services increases. The global market for streaming services is estimated to reach $688.7 billion by 2024. For cybercriminals, the widespread adoption of streaming services offers new, potentially lucrative attack vector. For example, just hours after Disney + was launched last November, thousands of accounts were hacked and people’s passwords and email details were changed. The criminals sold the compromised accounts online for between $3 and $11.

Even established services, such as Netflix and Hulu, are prime targets for distributing malware, stealing passwords and launching spam and phishing attacks. The spike in the number of subscribers in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has provided cybercriminals with an even bigger pool of potential victims. In the first quarter of this year, Netflix added fifteen million subscribers—more than double what had been anticipated.

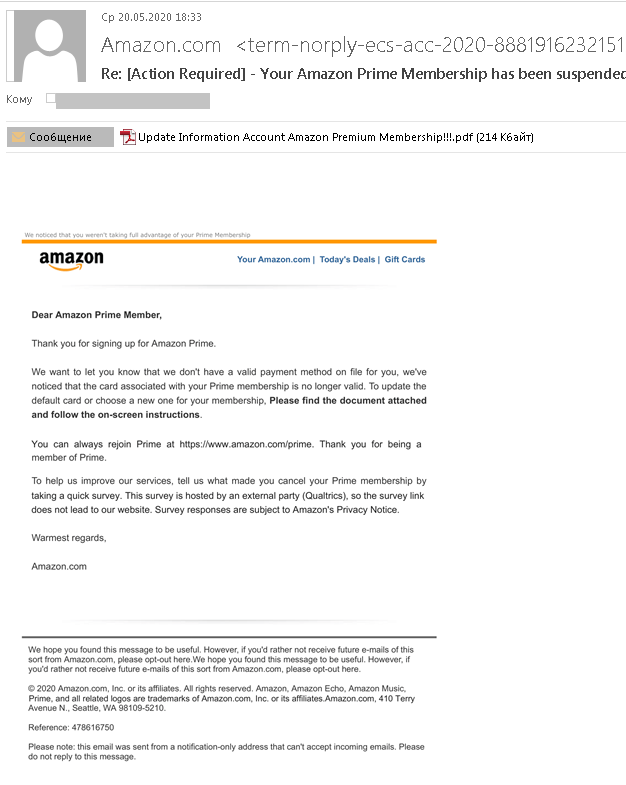

We took an in-depth look at the threat landscape as it relates to streaming services. Unsurprisingly, phishing is one of the approaches taken by cybercriminals, as they seek to trick people into disclosing login credentials or payment information.

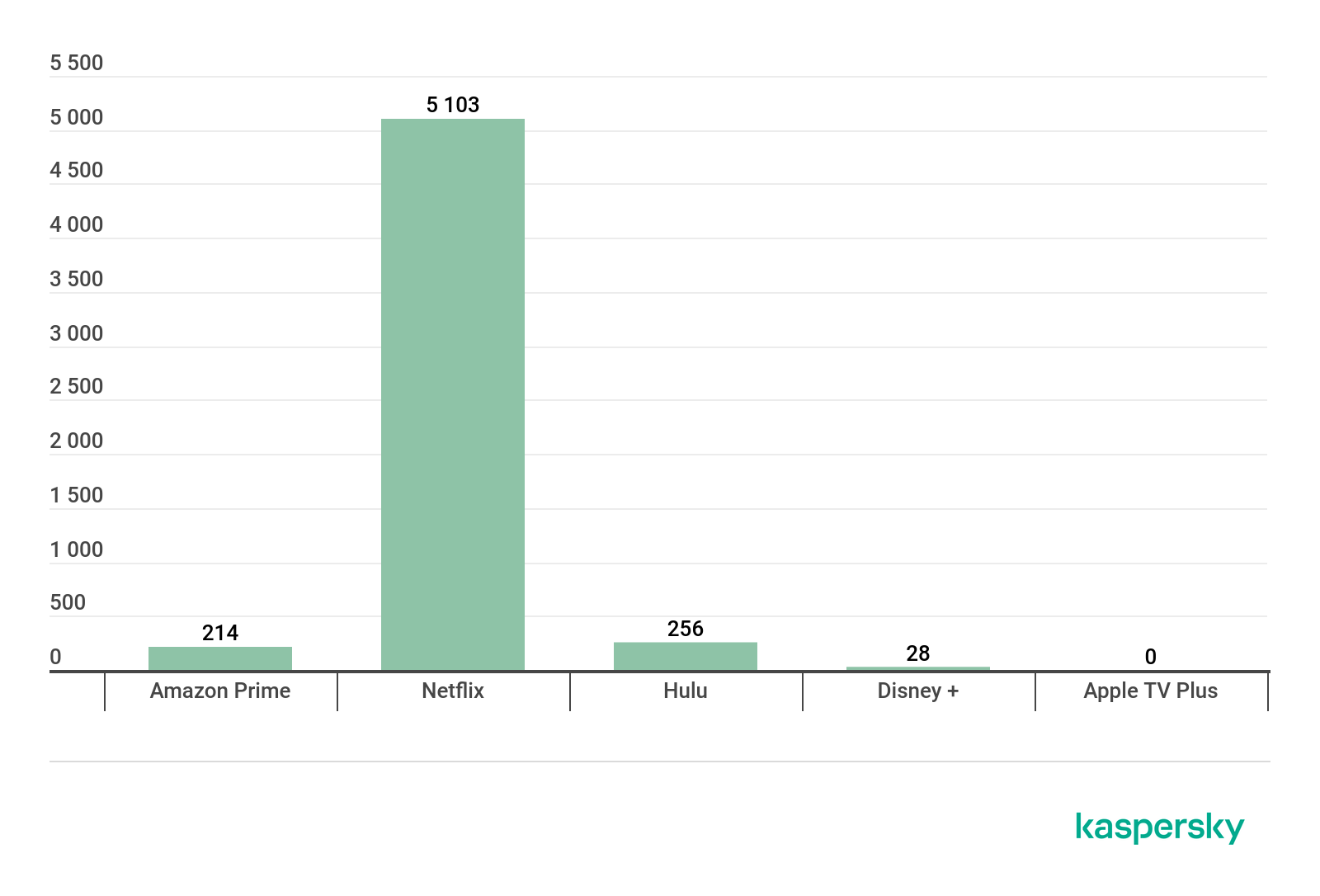

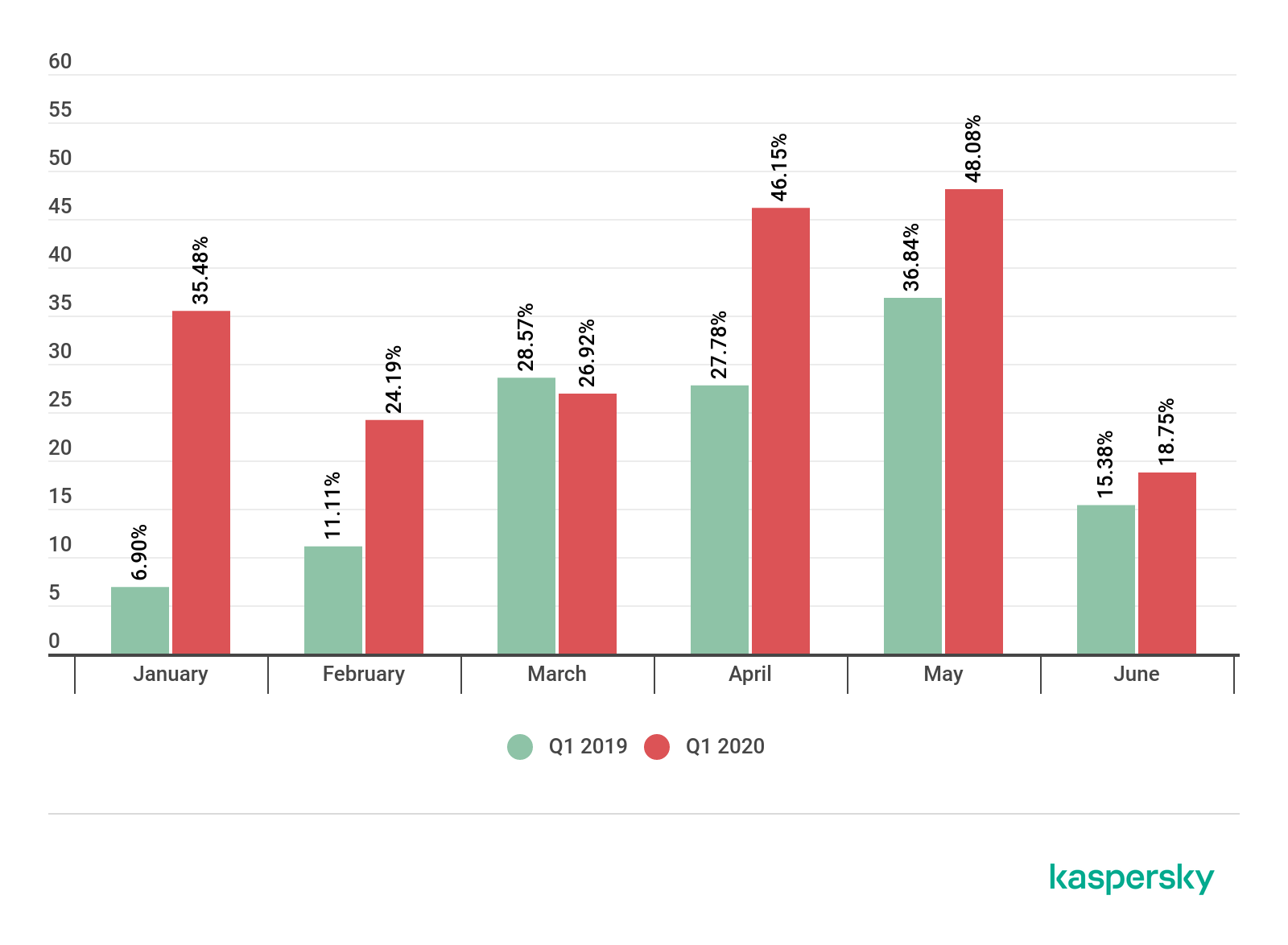

The criminals also capitalize on the growing interest in streaming services to distribute malware and adware. Typically, backdoors and other Trojans are downloaded when people attempt to gain access through unofficial means – by purchasing discounted accounts, obtaining a ‘hack’ to keep their free trial going, or attempting to access a free subscription. The chart below shows the number of people that encountered various threats containing the names of popular streaming platforms while trying to access these platforms through unofficial means between January 2019 and 8 April 2020:

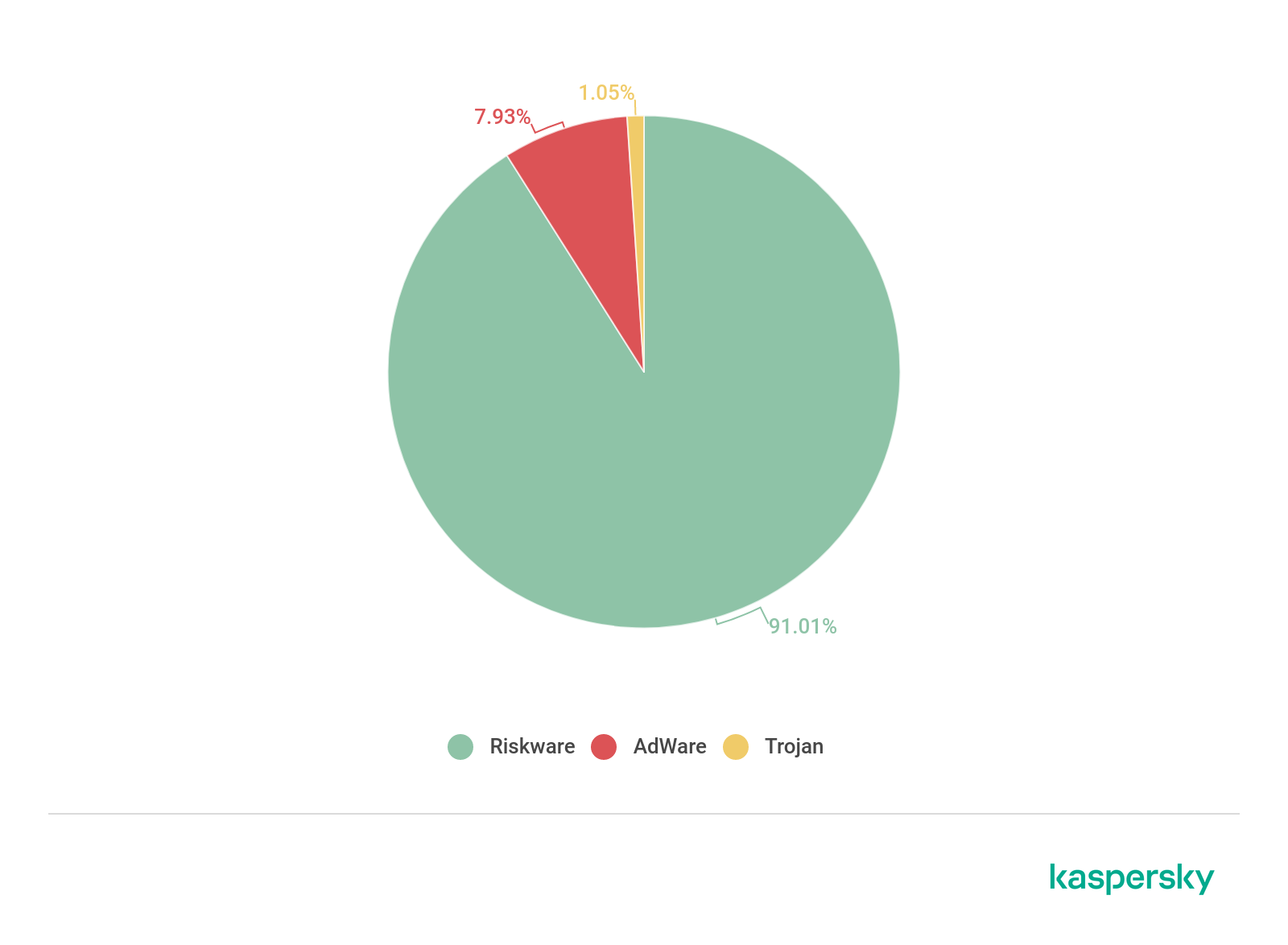

The chart below shows the mix of malicious programs disguised under the name of popular streaming platforms between January 2019 and 8 April 2020:

You can read the full report here, including our guidance on how to avoid phishing scams and malware related to streaming services.

Threats facing digital education

Online learning became the norm in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as classrooms and lecture theatres were forced to close. Unfortunately, many educational institutions did not have proper cyber-security measures in place, putting online classrooms at increased risks of cyber-attacks. On 17 June, Microsoft Security Intelligence reported that the education industry accounted for 61 percent of the 7.7 million malware encounters by enterprises in the previous 30 days – more than any other sector. In addition to malware, educational institutions also faced an increased risk of data breaches and violations of student privacy.

We recently published an overview of the threats facing schools and universities, including phishing related to online learning platforms and video conferencing applications, threats camouflaged as applications related to online learning and DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks affecting education.

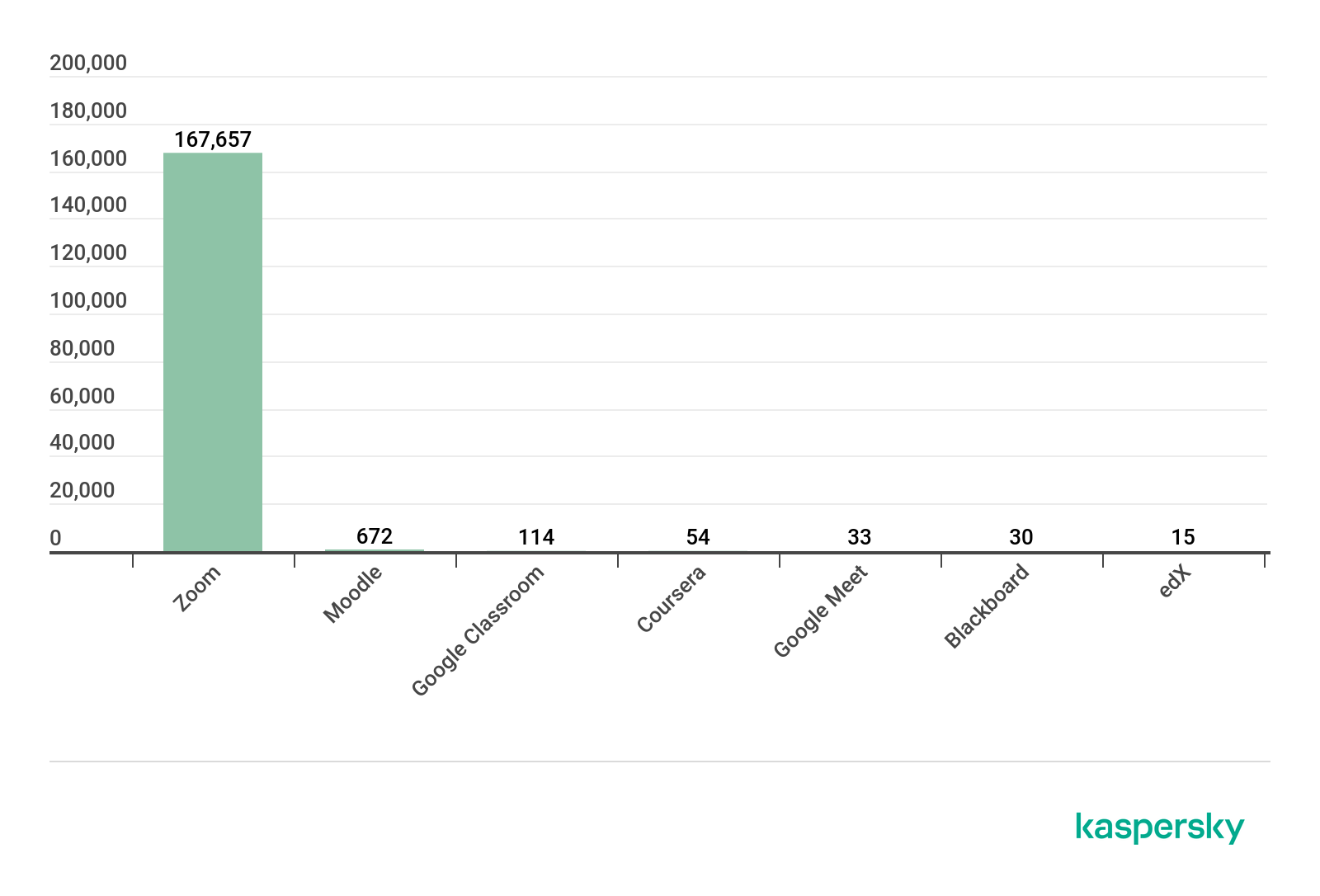

In the first half of 2020, 168,550 people encountered various threats disguised as popular online learning platforms – a massive increase compared to just 820 in the same period the previous year.

The platform used most frequently as a lure was Zoom, with 99.5 per cent of detections, no surprise given the popularity of this platform.

The overwhelming majority of threats distributed under the guise of legitimate video conferencing and online learning platforms were riskware and adware. Adware bombards users with unwanted adverts, while riskware consists of various files – including browser bars, download managers and remote administration tools – that may carry out various actions without consent.

In Q1 2020, the total number of DDoS attacks increased globally by 80 per cent when compared to the same period in 2019: and a large proportion of this increase can be attributed to attacks on distance e-learning services.

The number of DDoS attacks affecting educational resources that occurred between January and June this year increased by at least 350 per cent when compared to the same period in 2019.

It’s likely that online learning will continue to grow in the future and cybercriminals will seek to exploit this. So it’s vital that educational institutions review their cyber-security policy and adopt appropriate measures to secure their online learning environments and resources.

You can read our full report here.

Undeletable adware on smartphones

We’ve highlighted the issue of intrusive advertisements on smartphones a number of times in the past (you can find recent posts here and here). While it can be straightforward to remove adware, there are situations where it’s much more difficult because the adware is installed in the system partition. In such cases, trying to remove it can cause the device to fail. In addition, ads can be embedded in undeletable system apps and libraries at the code level. According to our data, 14.8 per cent of all users attacked by malware or adware in the last year suffered an infection of the system partition.

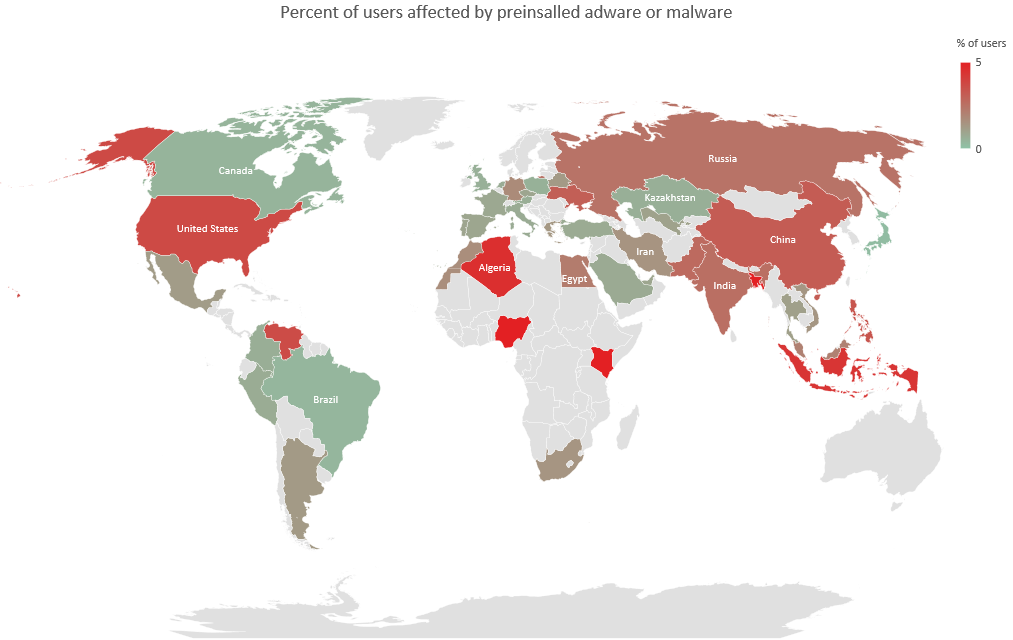

We have observed two main strategies for introducing undeletable adware onto a device. First, the malware obtains root access and installs adware in the system partition. Second, the code for displaying ads (or its loader) gets into the firmware of the device even before reaches the consumer. Our data indicates that between one and 5 per cent people running our mobile security solutions have encountered this. In the main, these are owners of smartphones and tablets of certain brands in the lower price segment. For some popular vendors offering low-cost devices, this figure reaches 27 per cent.

Since the Android security model assumes that anti-virus is a normal app, it is unable to do anything adware or malware in system directories, making this a serious problem.

Our investigations show that the focus of some mobile device suppliers is on maximizing profits through all kinds of advertising tools, even if such tools cause inconvenience to device owners. If advertising networks are ready to pay for views, clicks, and installations regardless of their source, it makes sense for them to embed ad modules into devices to increase the profit from each device sold.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh