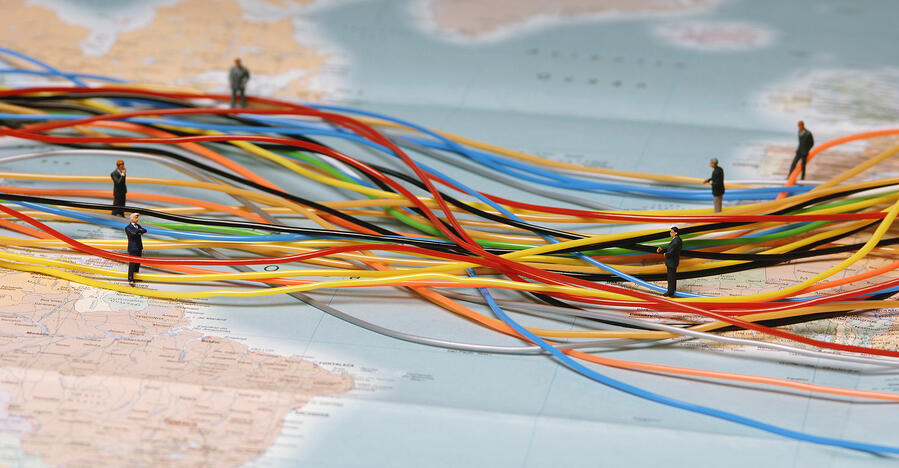

Here's how we could adopt a radical shift in thinking about open government data

It's one of the biggest clichés of today: data is the new oil. But then, clichés are clichés because they are true. One of the largest data reservoirs, which has not yet been sufficiently tapped, is government data. Governments all around the world collect vast amounts of data. The data collected by the government can, for example, include the following: With the ongoing digital transformation, more data is collected every year and more data is also being transferred from old paper files into new digital formats. But while there is incredible power in this data, it’s not being sufficiently utilized. One reason for this is that most government bodies are not particularly well-equipped to harness this potential. And it’s clear why: Government bodies have their own tasks within the public administration that they need to focus on. They also usually have limited resources and lack the required entrepreneurial spirit. One way to tackle this deficiency is for governments to make their data open to the public. This effort is called “open government data” and most governments are involved in it. We can already see many examples of successful use of government data by companies, like the map or weather forecast apps that heavily rely on data provided by governments that nearly everyone uses. But there are countless other ways the government data is used. For example, you may find it handy to know about the sitorsquat app that can help you find a clean public restroom in your town. One of the international organizations pushing the open government agenda is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Every two years, the OECD publishes its OURdata Index, which measures the availability, accessibility, and reuse of government data. The three most successful OECD countries in the index are South Korea, France, and Ireland. If you want to know how your country scores in the index, take a look at the OECD report. Despite significant progress in this area, most governments are still not doing enough to make government data available to the public and to allow researchers and companies to process this data. It is therefore good to see that the European Union is also stepping up its game in this area. In November last year, the European Commission published its draft Data Governance Act. The proposal aims to create a framework for greater reuse of data by strengthening various data-sharing mechanisms in the EU. One of the key parts of the proposal deals with the reuse of government data. The current draft prohibits government bodies from entering into exclusive data-sharing arrangements and sets out some basic conditions under which the data shall be made available to the public. This certainly makes good sense if we want to ensure that government data is available to everyone. However, what I see as a missed opportunity is the fact that the proposal also explicitly confirms that it does not create any obligation for government bodies to make the data available for reuse. It will thus still be up to the member states to decide what data they will make public. And this is what inspired me to write this blog. Isn’t this approach fundamentally flawed? Shouldn’t the default position be: all government data is made public, except for the data designated by the government as not suitable for being made available? This is how it could work: Any dataset processed by any government body would be required to be made public in an appropriate digital format. To the extent that the dataset contains personal data, state secrets, or business confidential information, the data would need to be anonymized or aggregated. There would also be an exhaustive list of exceptions from the requirement to publish the data, such as national security reasons. However, the default position would be clear: If you can’t fit in the exception, you must publish the data. The launch of this initiative would certainly be painful, as many government databases were not built with a vision of being made publicly available. These technical difficulties will, however, will go away once governments start building and updating their databases mindful of these new requirements. There are a couple of clear arguments for why this radical change to mandatory openness makes sense. Without the strict obligation to publish the data, the government bodies have little incentive to make data available. It is extra work for them, plus their good deed may backfire as the published data may reveal deficiencies in the way they govern. Secondly, opening data to the public enhances government transparency and increases the trust of the public in the government. However, my strongest argument for the change of the approach is as follows: No one disputes that government data has value and that governments themselves are unable to fully leverage it, for a variety of reasons. At the same time, while it’s easy to see the value of some government data (such as geographic or meteorological information), there are many other datasets that the government may consider useless for private use. Such datasets would hardly ever be made public voluntarily, as the government would not see the reason to do it. The government is, however, not best equipped to see the value in the data. This should be left to companies and researchers. Sometimes a dataset which seems unusable at first sight may, after further research and analysis, reveal valuable insights and be transformed into fascinating use cases. Unless we open the data to the public and let the companies and researchers dig into this data, we will never find out. There is one more argument. Probably the only one you need to successfully argue for mandatory openness of the government data. Government data is collected by the government on behalf of its citizens. It is owned by citizens and so every citizen should be allowed to have access to it — period.

Open government data

Will the EU help?

Arguments for a radical shift in thinking about open government data

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh