Figures of the year

In 2020:

- The share of spam in email traffic amounted to 50.37%, down by 6.14 p.p. from 2019.

- Most spam (21.27%) originated in Russia.

- Kaspersky solutions detected a total of 184,435,643 malicious attachments.

- The email antivirus was triggered most frequently by email messages containing members of the Trojan.Win32.Agentb malware family.

- The Kaspersky Anti-Phishing component blocked 434,898,635 attempts at accessing scam sites.

- The most frequent targets of phishing attacks were online stores (18.12 per cent).

Trends of the year

Contact us to lose your money or account!

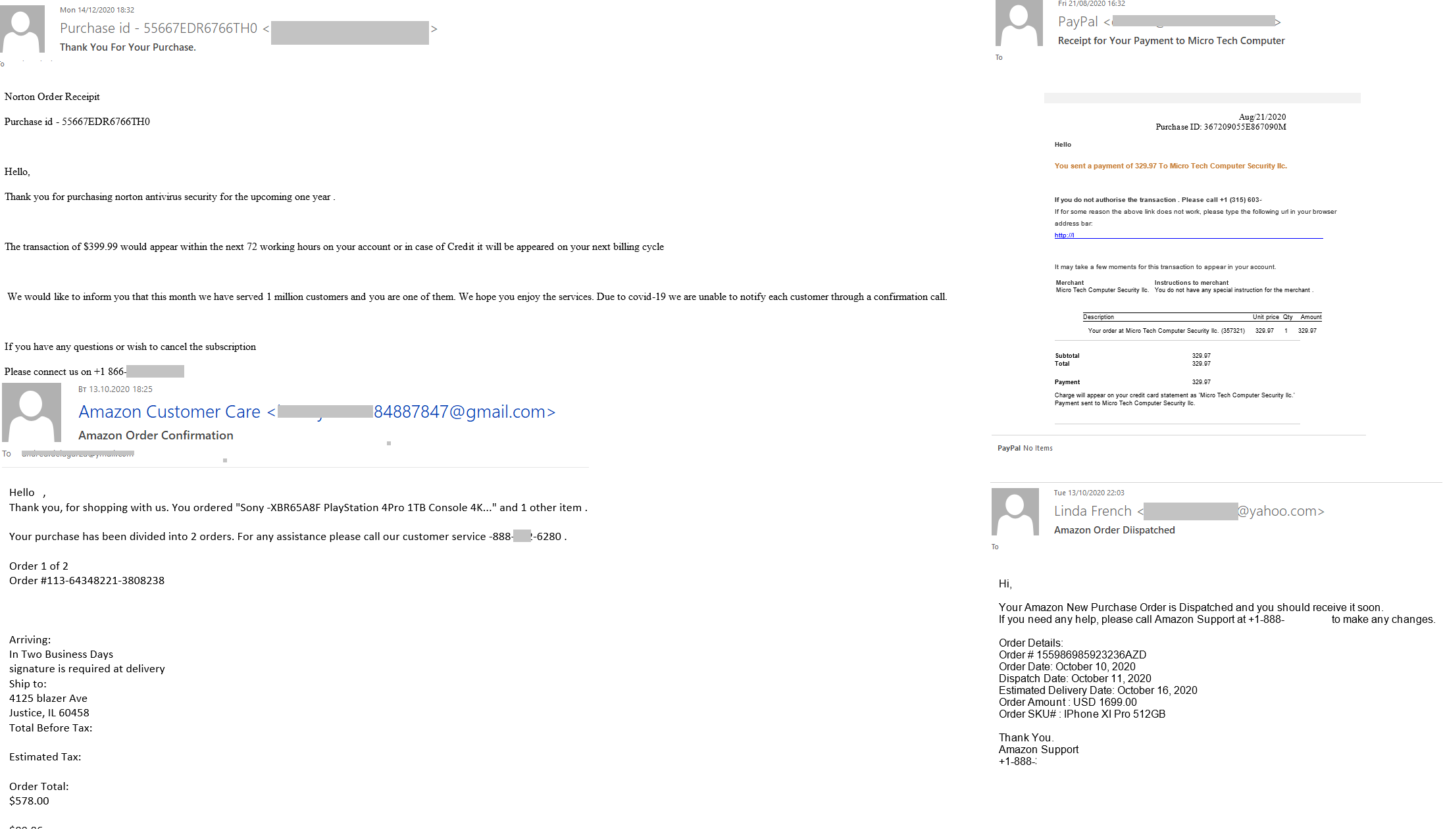

In their email campaigns, scammers who imitated major companies, such as Amazon, PayPal, Microsoft, etc., increasingly tried to get users to contact them. Various pretexts were given for requesting the user to get in touch with “support”: order confirmation, resolving technical issues, cancellation of a suspicious transaction, etc. All of these messages had one thing in common: the user was requested to call a support number stated in the email. Most legitimate messages give recipients constant warnings of the dangers of opening links that arrive by email. An offer to call back was supposed to put the addressees off their guard. Toll-free numbers were intended to add further credibility, as the support services of large companies often use these. The scammers likely expected their targets to use the provided phone number to get help instantly in a critical situation, rather than to look for a contact number or wait for a written response from support.

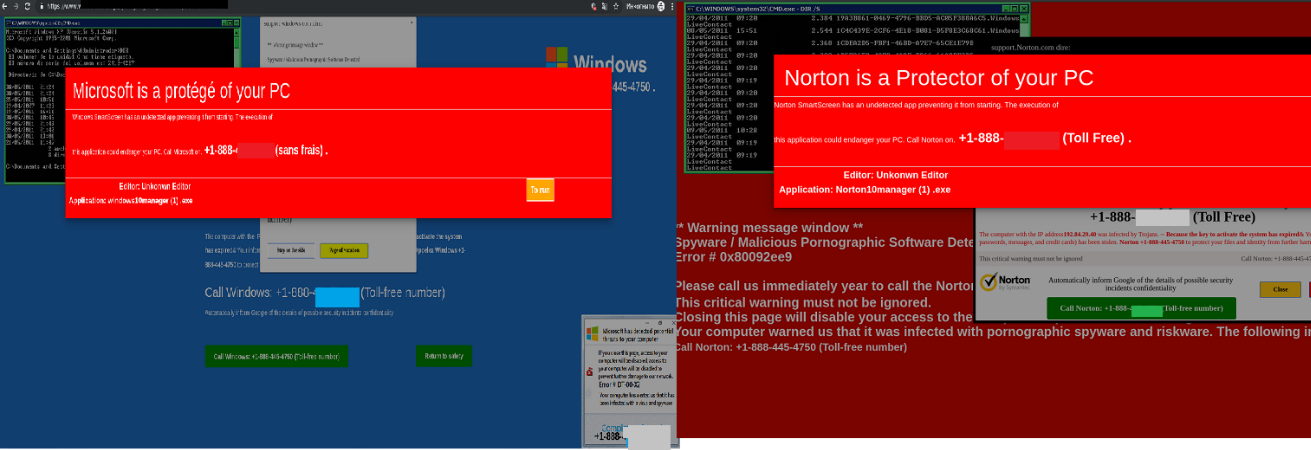

The contact phone trick was heavily used both in email messages and on phishing pages. The scammers were simply betting on the visitor to turn their attention to the number and unsettling warning message against the red background, rather than the address bar of the fake website.

We assume that those who called the numbers were asked to provide the login and password for the service that the scammers were imitating, or to pay for some diagnostics and troubleshooting services.

Reputation, bitcoins or your life?

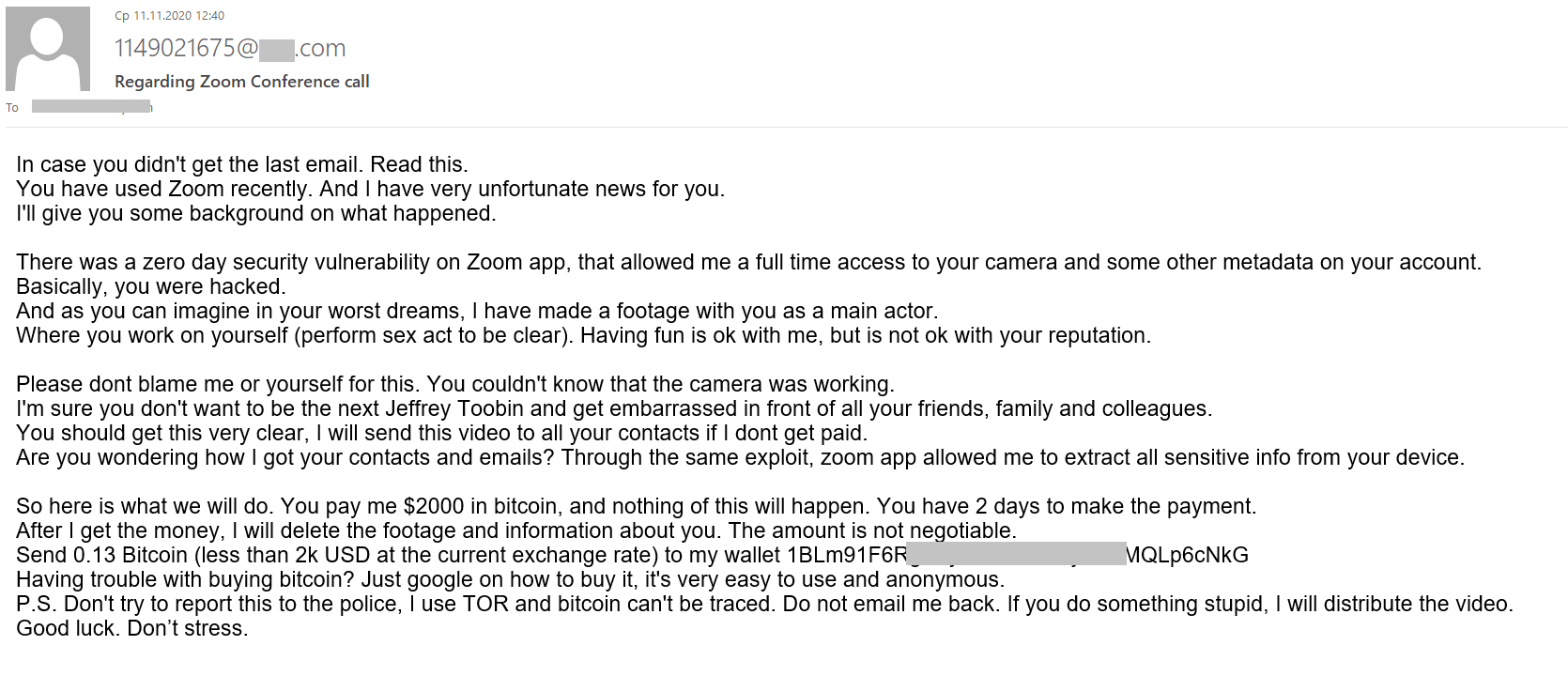

In 2020, Bitcoin blackmailers stuck to their old scheme, demanding that their victims transfer money to a certain account and threatening adversity for failure to meet their demands. Threats made by extortionists grew in diversity. In most cases, scammers, as before, claimed to have used spyware to film the blackmail victim watching adult videos. In a reflection of the current trends for online videoconferencing, some email campaigns claimed to have spied on their victims with the help of Zoom. This year, too, blackmailers began to take advantage of news sensations to add substance to their threats. This is very similar to the techniques of “Nigerian” scammers, who pose as real political figures or their relatives, offering tons of money, or otherwise link their messages with concurrent global events. In the case of bitcoin blackmail, the media component was supposed to be a strong argument in the eyes of the victim for paying the ransom without delay, so cybercriminals cited the example of media personalities whose reputation suffered because of an explicit video being published.

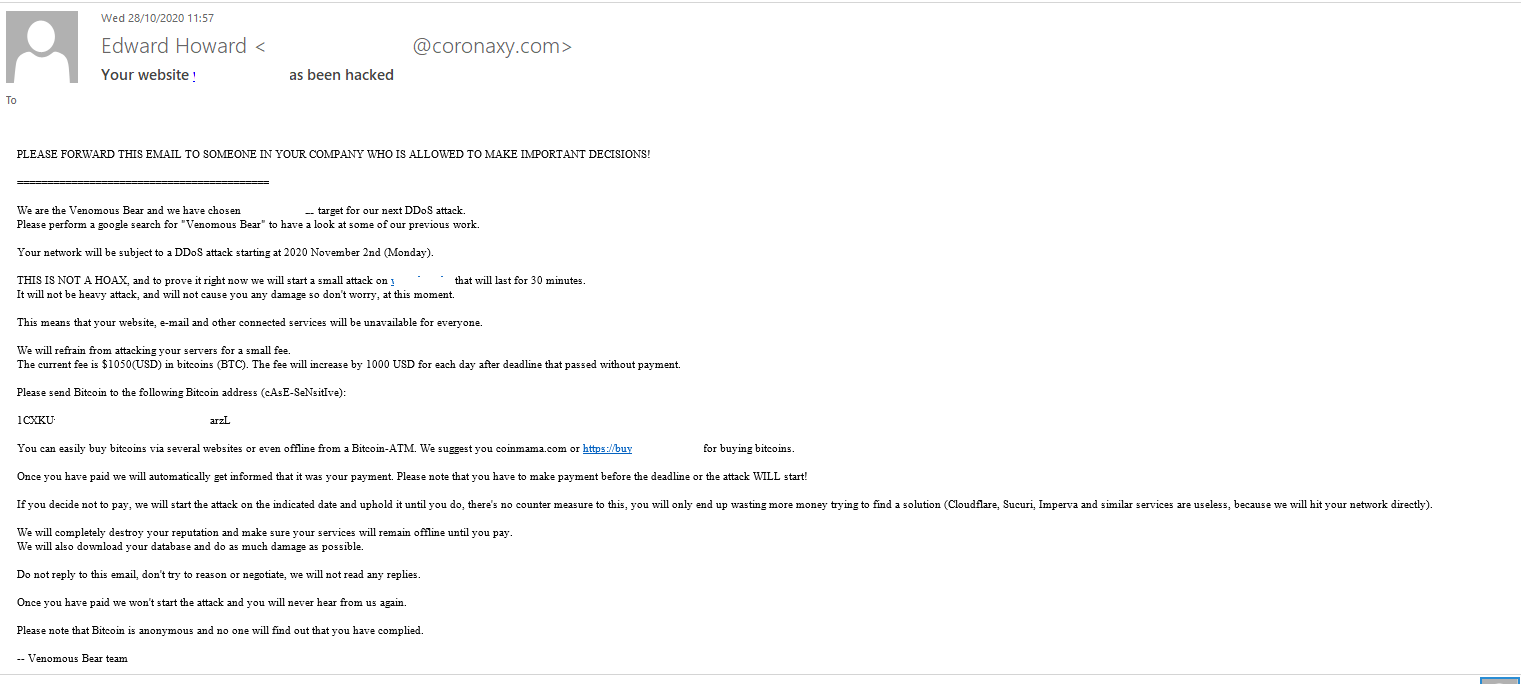

This year, we have seen threats made against companies, too. A company was told to transfer a certain amount to a Bitcoin wallet to prevent a DDoS attack that the cybercriminals threatened to unleash upon it. They promised to provide a demonstration to prove that their threats were real: no one would be able to use the services, websites or email of the company under attack for thirty minutes. Interestingly, the cybercriminals did not limit their threats to DDoS. As with blackmail aimed at individuals, they promised to damage the company’s reputation even more, should it fail to pay up, by stealing confidential information, specifically, its business data. The attackers introduced themselves as well-known APT groups to add weight to their threats. For example, in the screenshot below, they call themselves Venomous Bear, also known as Waterbug or Turla.

This year, we have seen threats made against companies, too. A company was told to transfer a certain amount to a Bitcoin wallet to prevent a DDoS attack that the cybercriminals threatened to unleash upon it. They promised to provide a demonstration to prove that their threats were real: no one would be able to use the services, websites or email of the company under attack for thirty minutes. Interestingly, the cybercriminals did not limit their threats to DDoS. As with blackmail aimed at individuals, they promised to damage the company’s reputation even more, should it fail to pay up, by stealing confidential information, specifically, its business data. The attackers introduced themselves as well-known APT groups to add weight to their threats. For example, in the screenshot below, they call themselves Venomous Bear, also known as Waterbug or Turla.

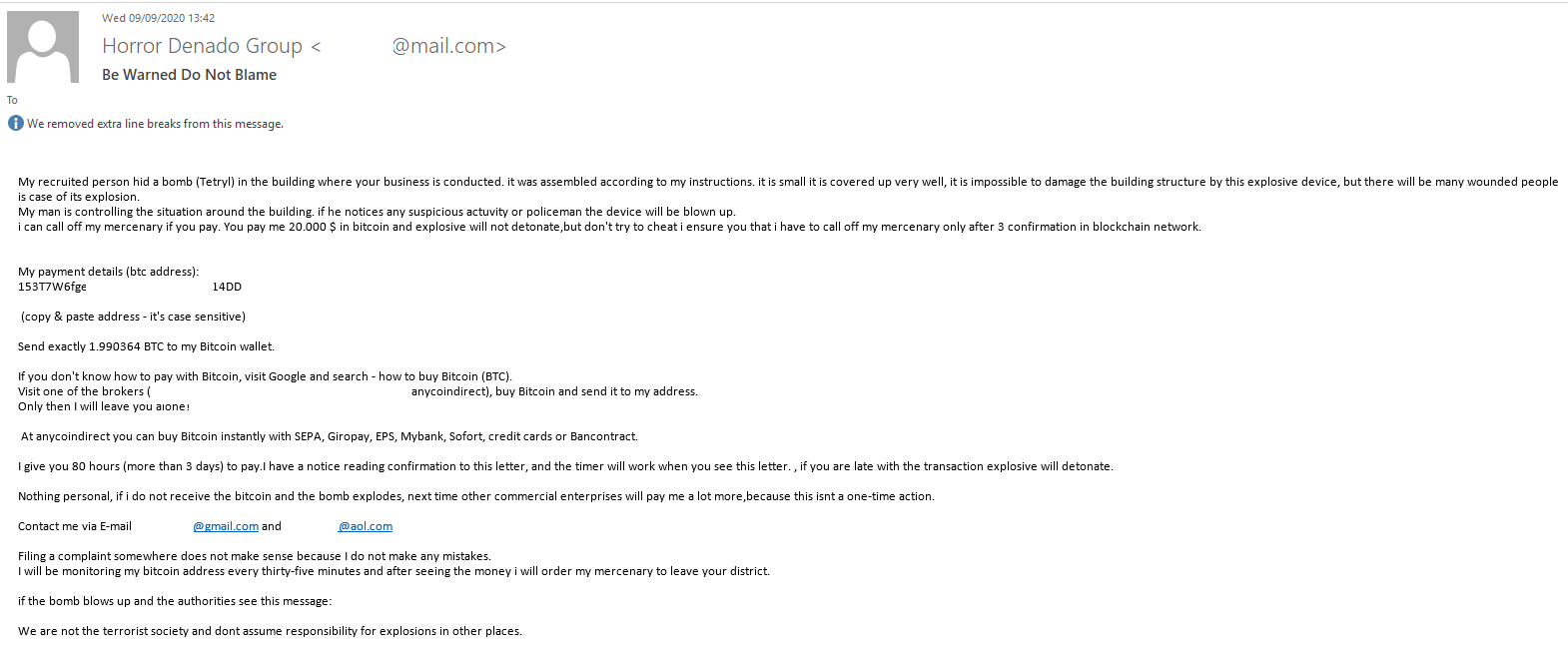

The senders of an email that talked about a bomb planted in company’s offices went much further with their threats. The amount demanded by the blackmailers was much larger than in previous messages: $20,000. To make their threats sound convincing enough, the cybercriminals provided details of the “attack”: an intention to blow up the bomb if the police intervened, the substance used, the explosive yield and plans to threaten other blackmail victims with the explosion.

Attacks on the corporate sector

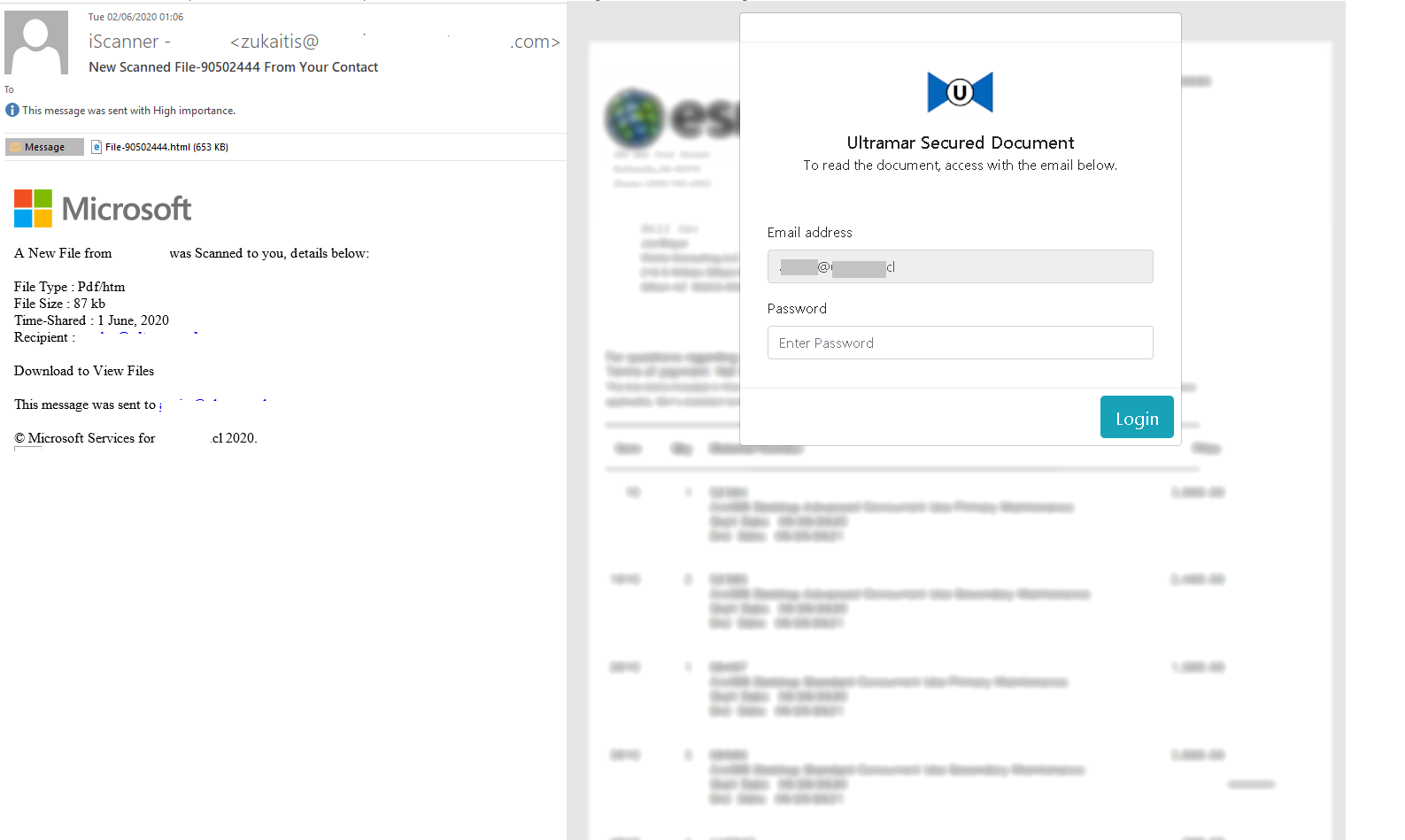

Theft of work accounts and infecting of office computers with malware in targeted attacks are the main risk that companies have faced this year. Messages that imitated business email or notifications from major services offered to view a linked document or attached HTML page. Viewing the file required entering the password to the recipient’s corporate email account.

Reasons given for asking users to open a link or attachment could be varied: a need to install an update, unread mail, quarantined mail or unread chat messages. The cybercriminals created web pages that were designed to look like they belonged to the company under attack. URL parameters including the corporate email address were pushed to the fake page with the help of JavaScript. This resulted in the user seeing a unique page with a pre-entered email address and a design generated to imitate the company’s corporate style. The appearance of that page could lull the potential victim into a false sense of security, as all they needed to do was enter their password.

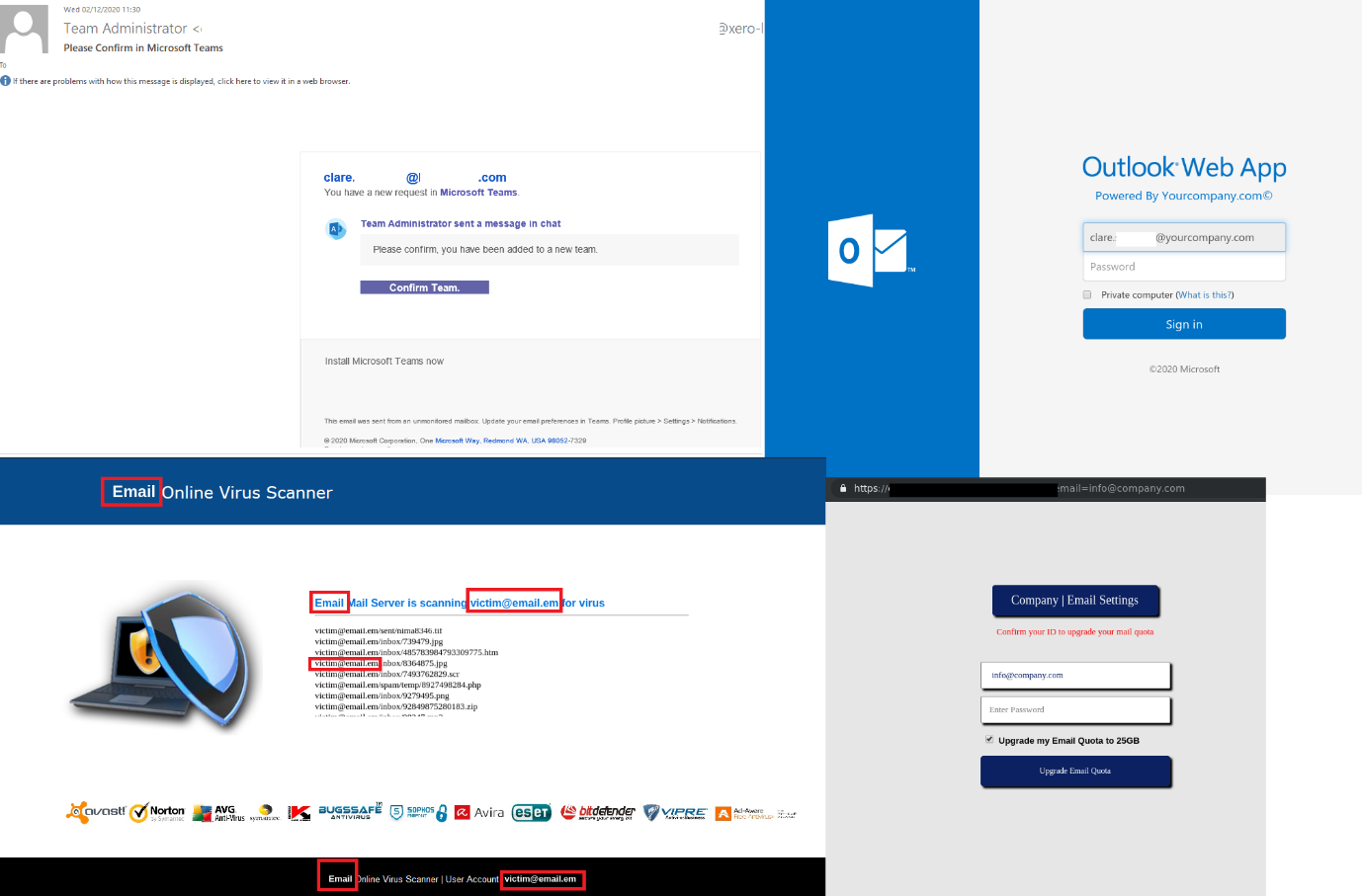

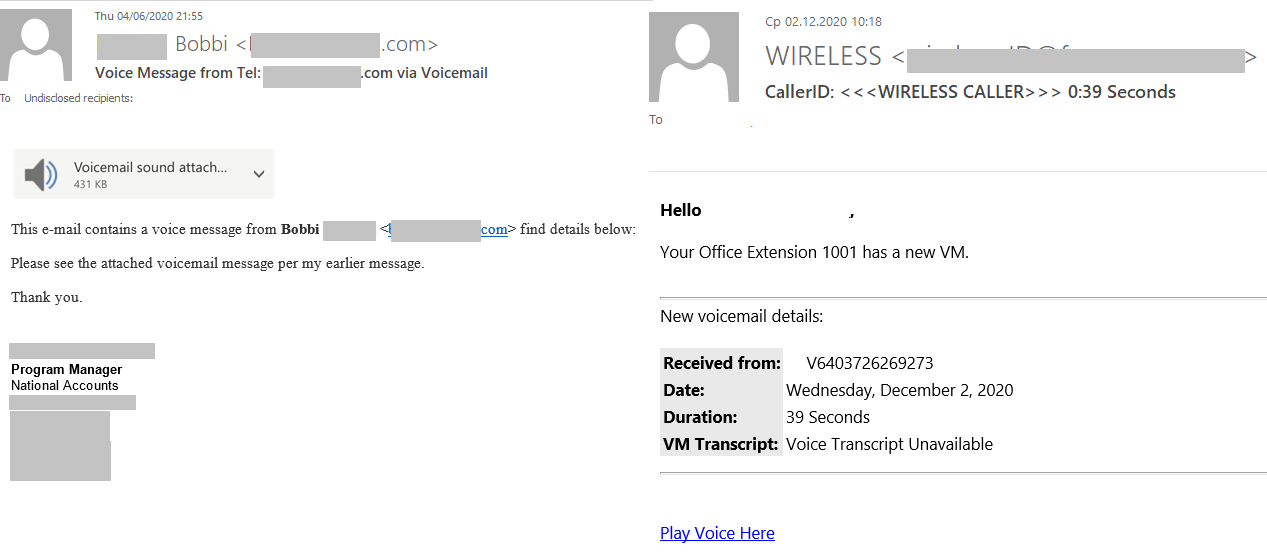

During this type of attacks scammers began to make broader use of “voice messaging”. The appearance of the messages imitated business email.

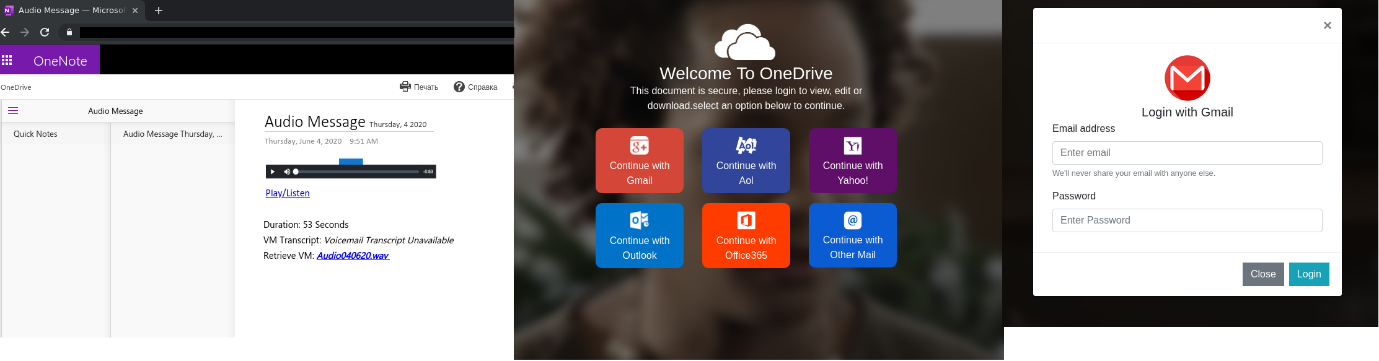

The link could lead directly to a phishing site, but there also was a more complex scenario, in which the linked page looked like an audio player. When the recipient tried playing the file, they were asked to enter the credentials for their corporate mailbox.

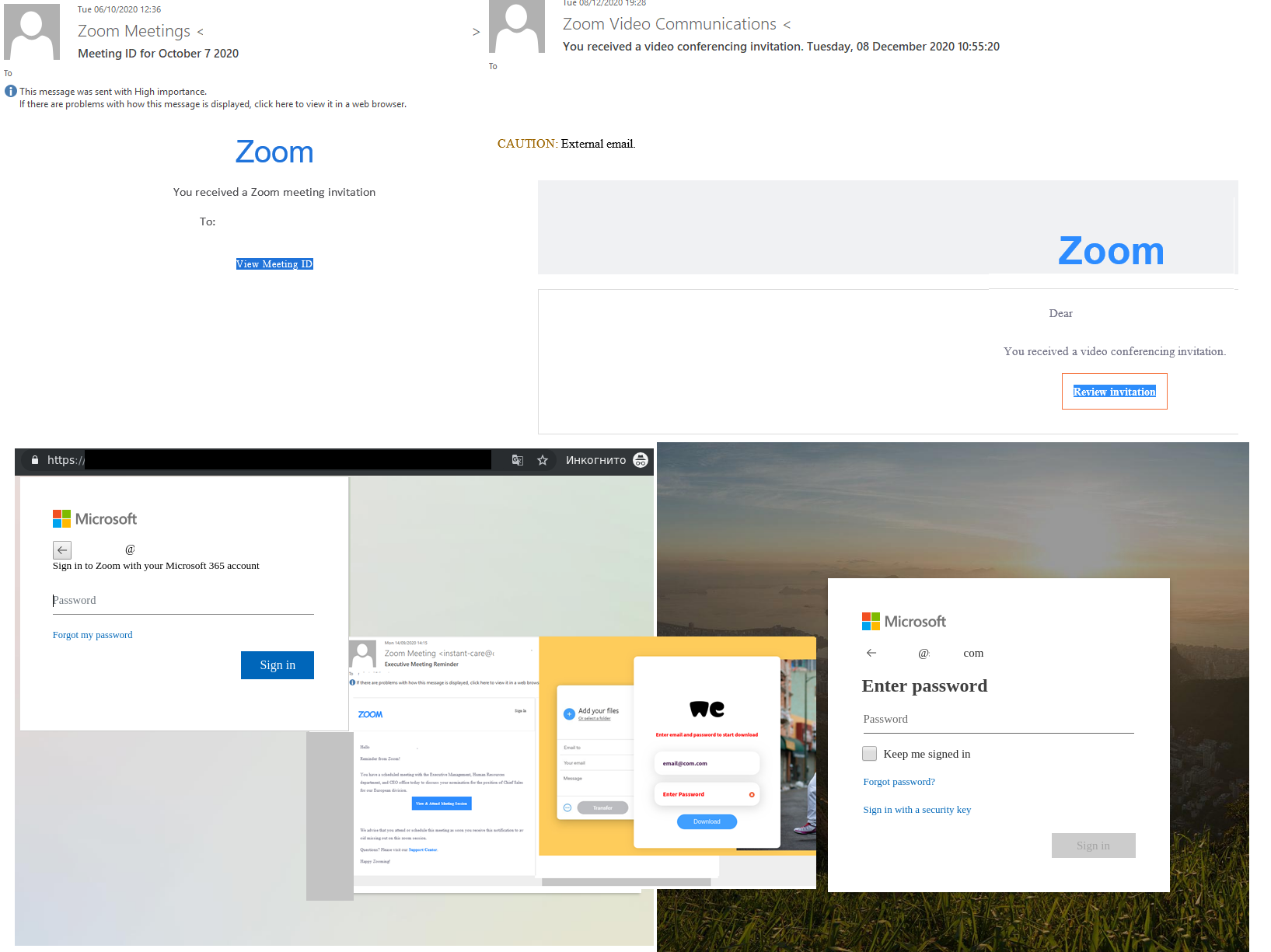

Demand for online videoconferencing amid remote work led to a surge in fake online meeting invitations. A significant distinctive feature, which should have alarmed the recipients of the fake invitations, were the details that the page was asking them to enter in order to join the meeting. To access a real Zoom meeting, you need to know the meeting ID and password. The fake videoconference links opened fake Microsoft and WeTransfer pages, which contained fields for entering the login and password for a work account.

Messengers targeted

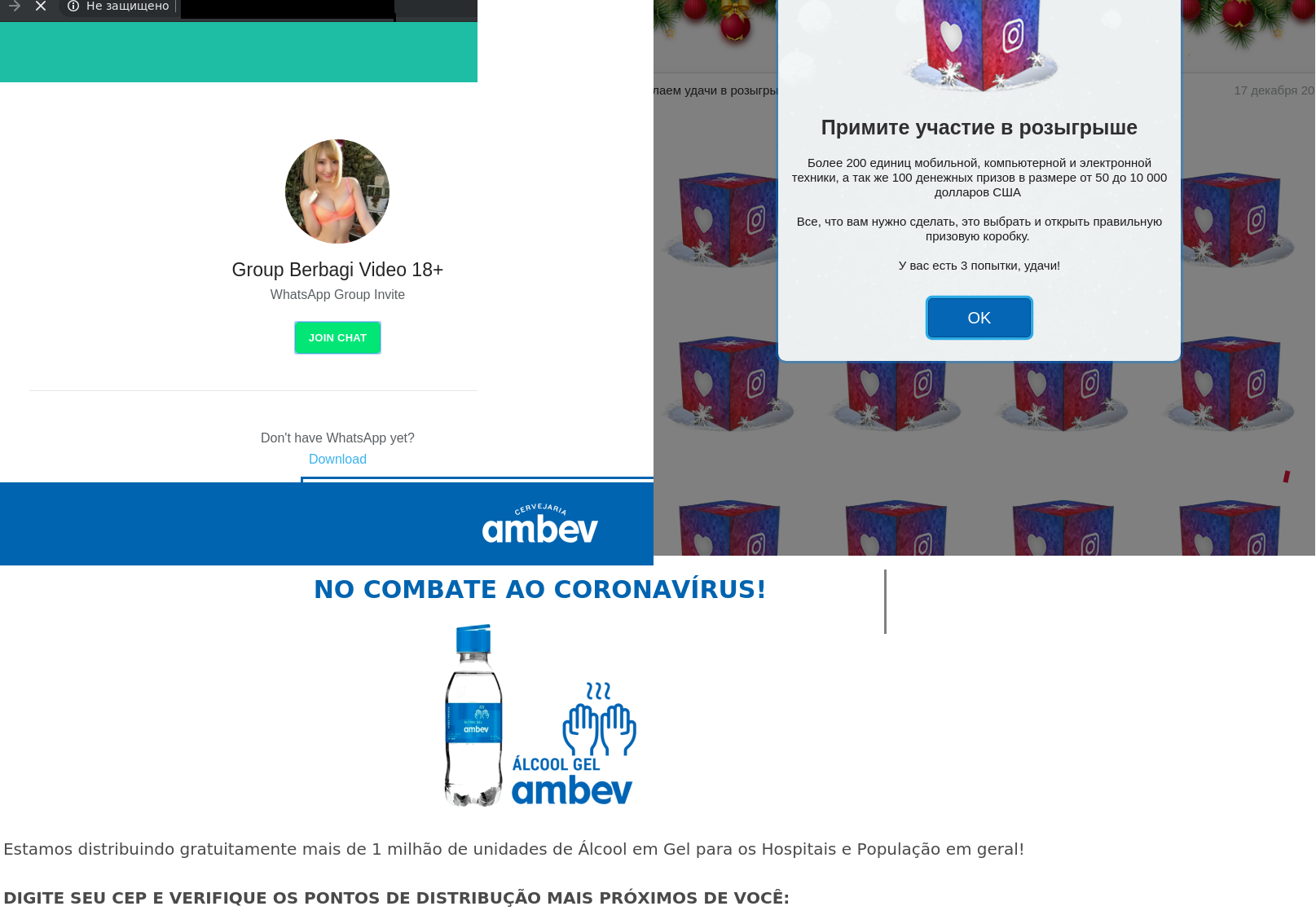

Scammers who were spreading their chain mail via social networks and instant messaging applications began to favor the latter. Message recipients, mostly in WhatsApp, were promised a discount or prize if they opened a link sent to them. The phishing web page contained a tempting message about a money prize, award or other, equally desirable, surprises.

The recipient had to fulfill two conditions: answer a few simple questions or fill out a questionnaire, and forward the message to a certain number of their contacts. Thus, the victim turned into a link in the spam chain, while subsequent messages were sent from a trusted address, thus avoiding anti-spam filters.

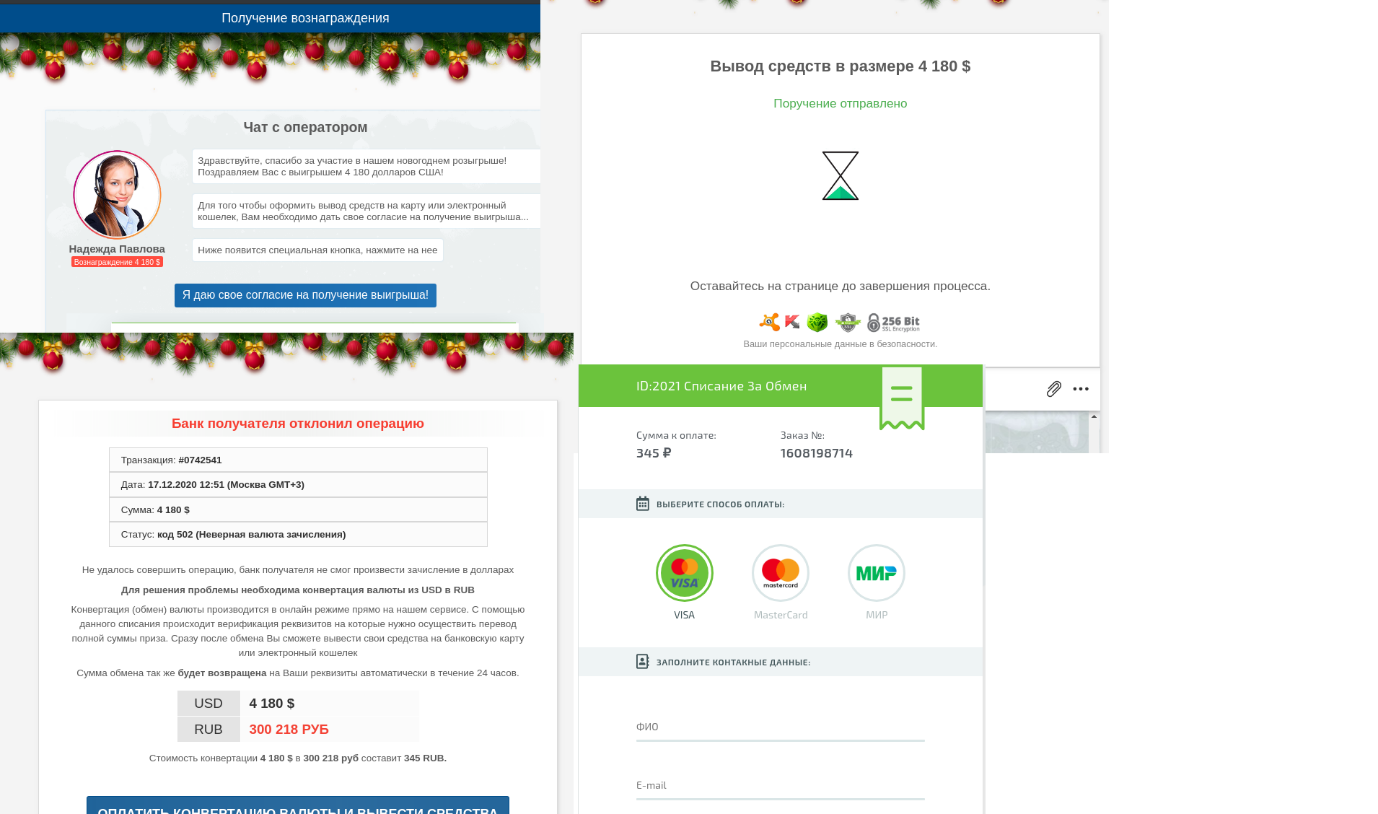

Besides that, a message from someone that the recipient knew would have much more credibility. Thus, the chain continued to grow, and the scammers went on enriching themselves. After all, even if the victim did fulfill the conditions, getting that promised prize proved not so simple, as the “lucky” recipient was urged to pay bank commission.

COVID-19

“Public relief” by spammers

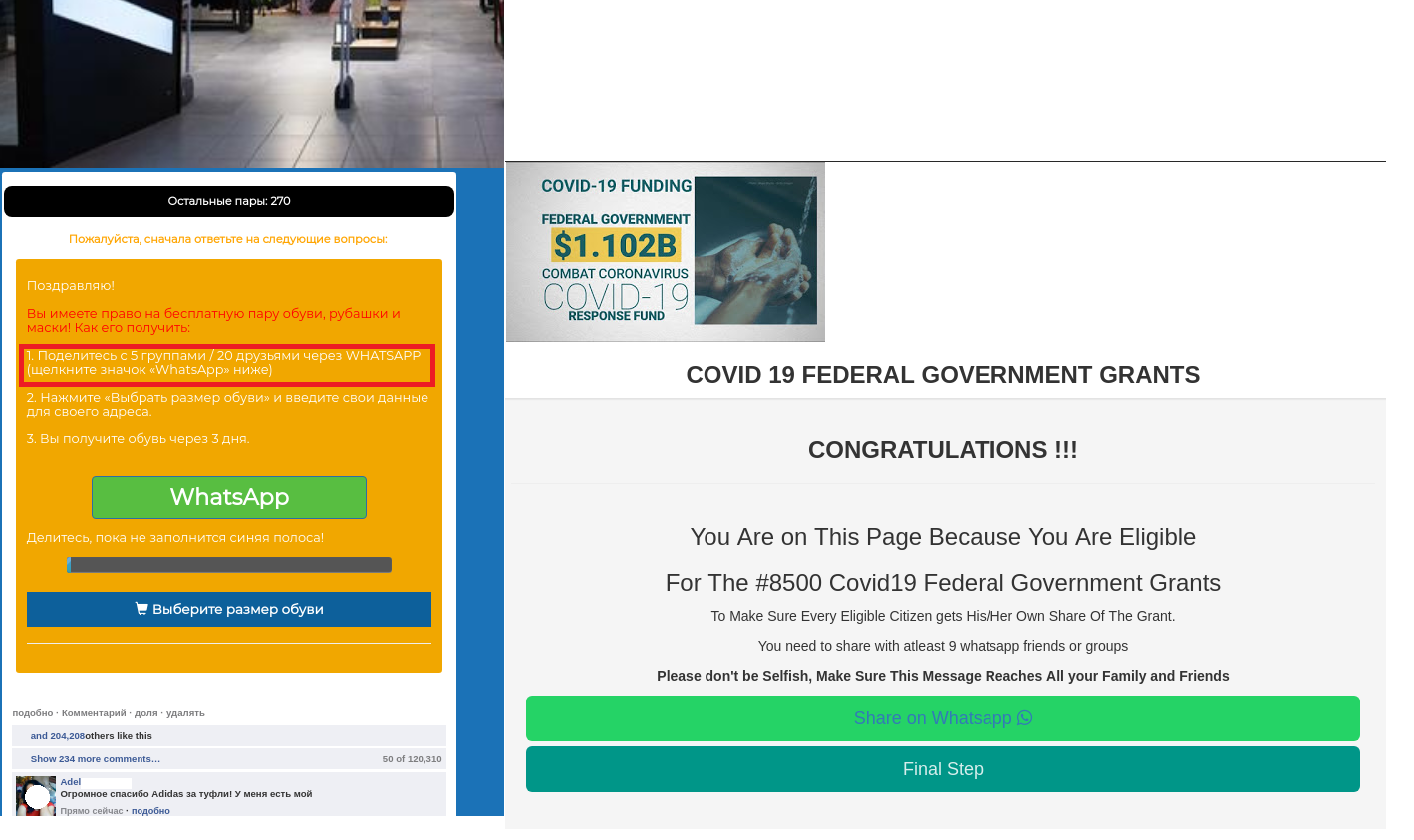

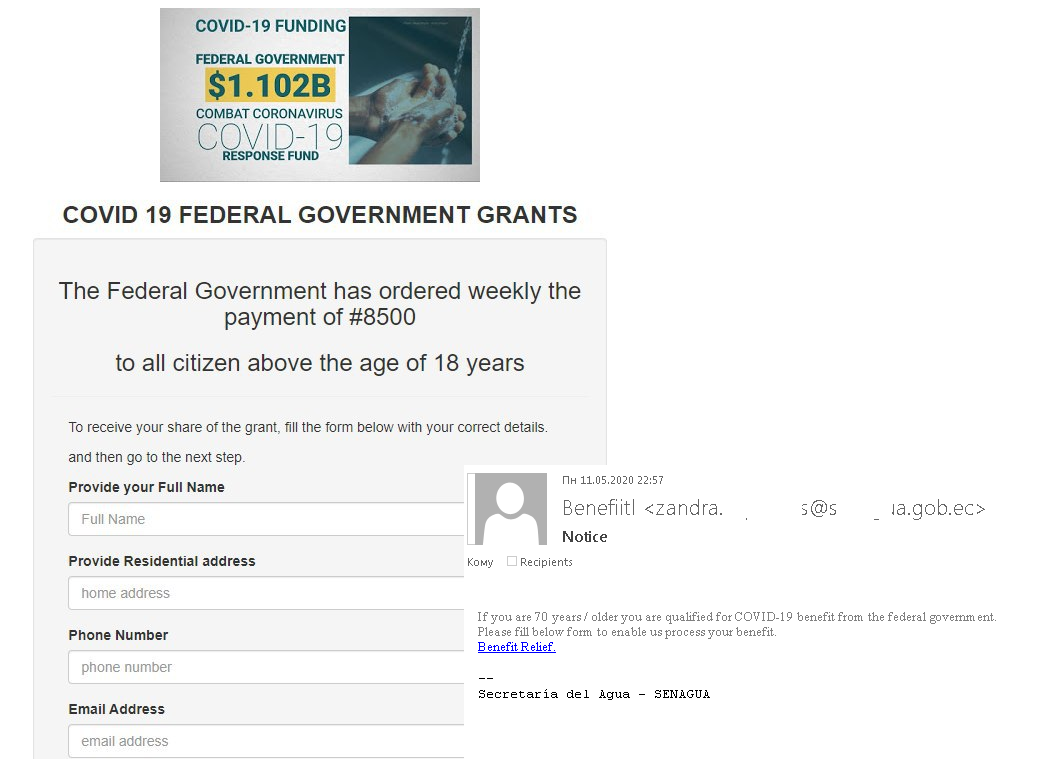

Many governments did their best to help citizens during the pandemic. That initiative, together with the fact that people on the whole were willing to get payouts, became a theme for spam campaigns. Both individuals and companies were exposed to the risk of being affected by cybercriminals’ schemes.

Messages offering financial aid to businesses hurt by the pandemic or to underprivileged groups could crop up in social media feeds or arrive through instant messaging networks. The main requirement for getting the funds was filling out a detailed personal questionnaire. Those who took the step found that a small commission was required as well. Real government payouts these days are made through public portals that also serve other purposes and do not require additional registration, questionnaires or commissions.

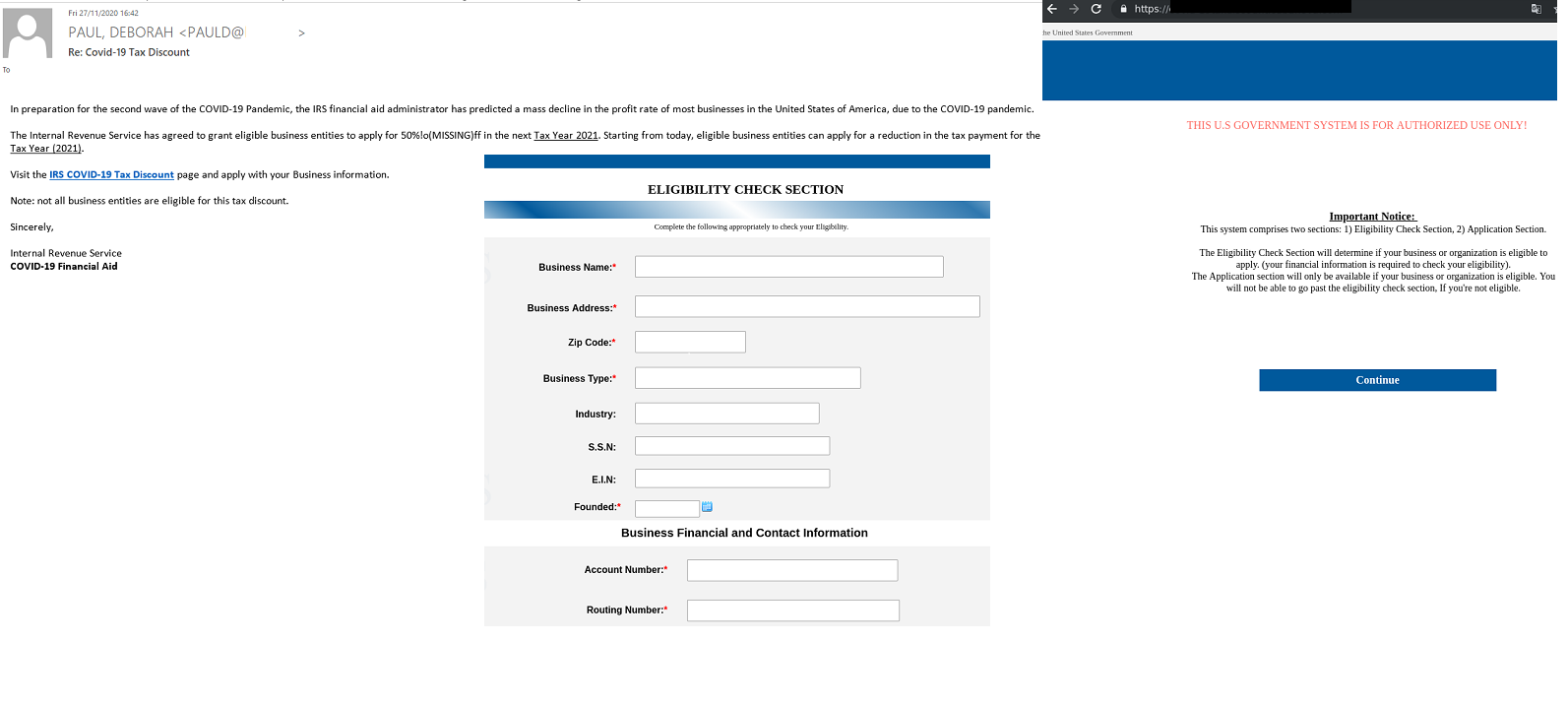

Cybercriminals who offered tax deductions to companies employed a similar scheme. As in the examples above, the reason provided for the easing of tax policy was the pandemic, and in particular, anticipation of a second wave of COVID-19.

However, offers of tax deductions and compensations were hiding not just the danger of losing money but losing one’s account to the scammers, too, as many of the messages contained phishing links.

Malicious links

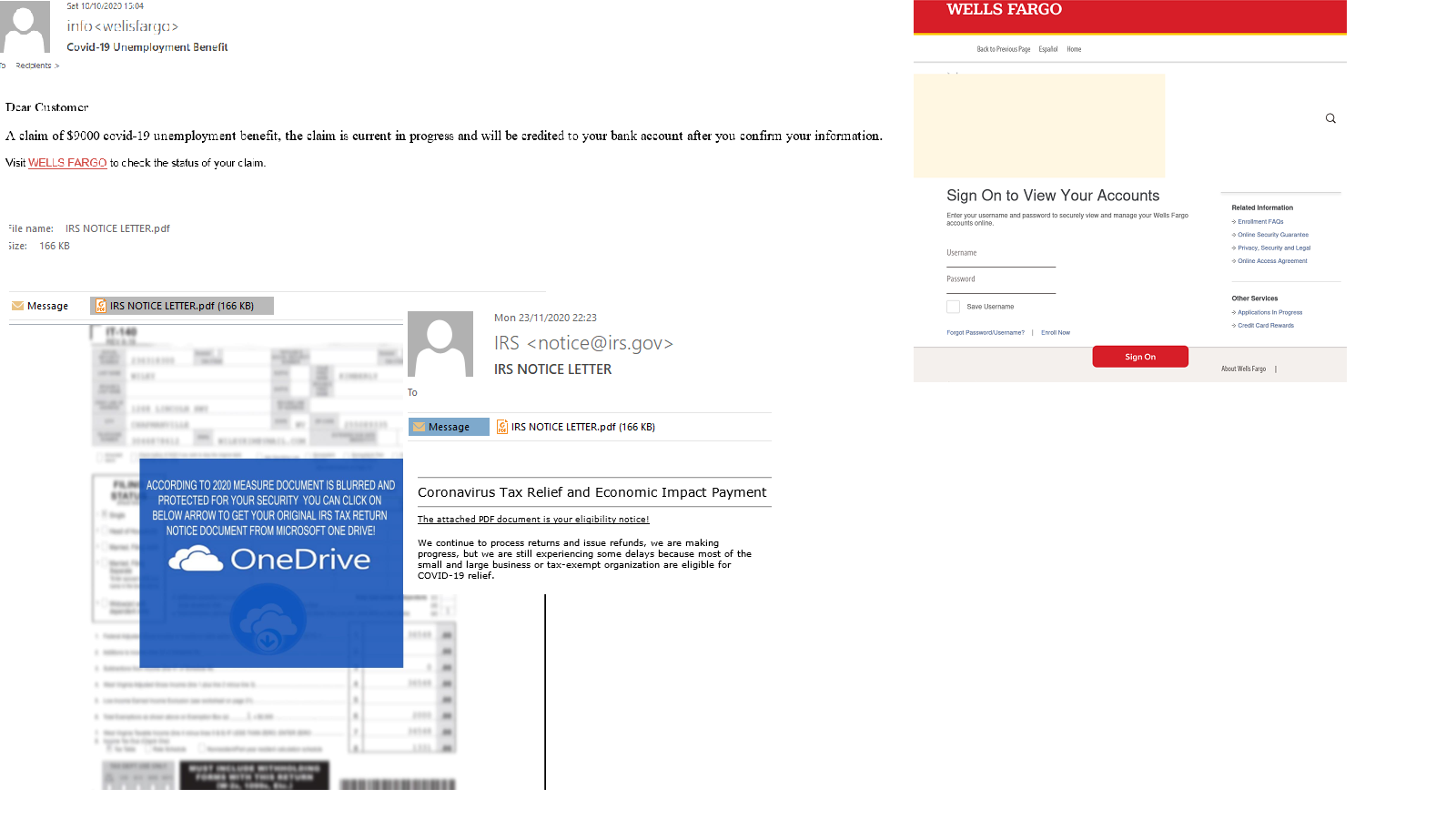

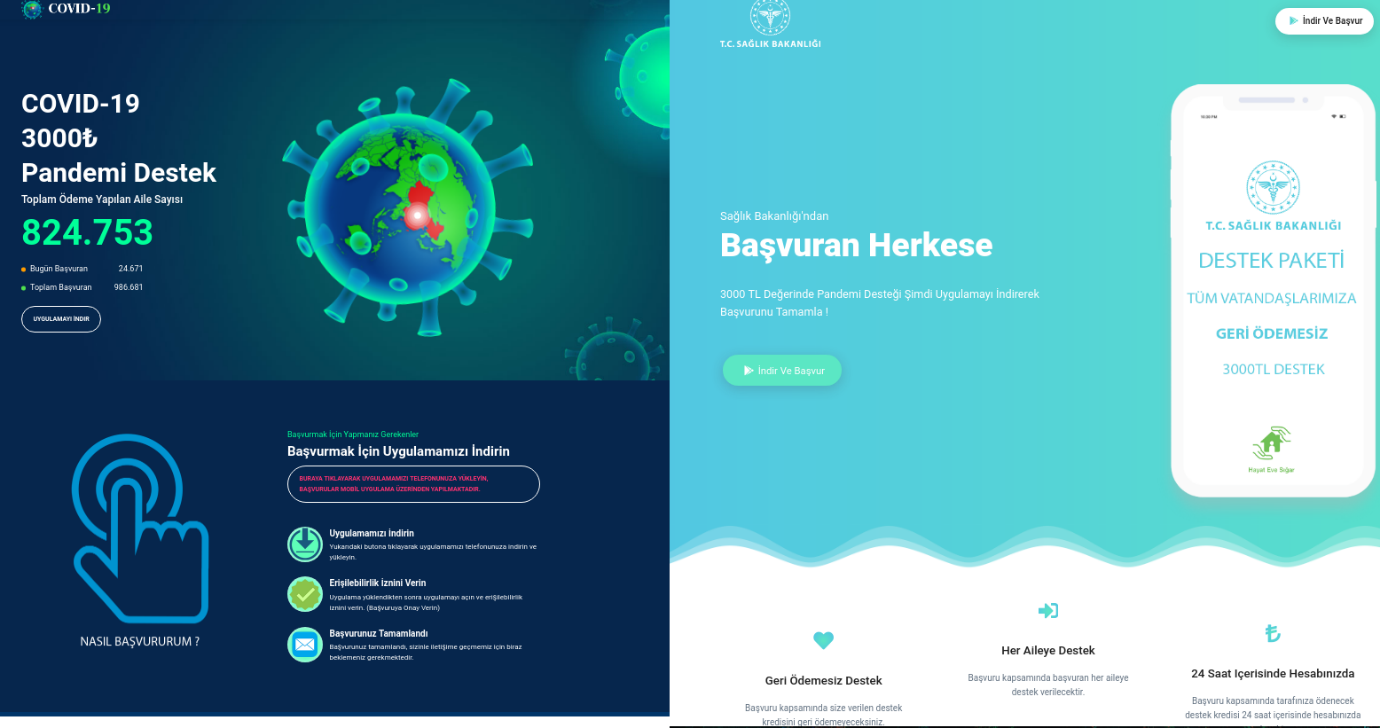

Email campaigns that promised compensation could also threaten computer security. Messages in Turkish, just as those mentioned earlier, offered a payout from Turkey’s Ministry of Health – not always mentioned by name – but getting the money required downloading and installing an APK file on the recipient’s smartphone. The attack was targeting Android users, and the downloadable application contained a copy of the Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.cf.

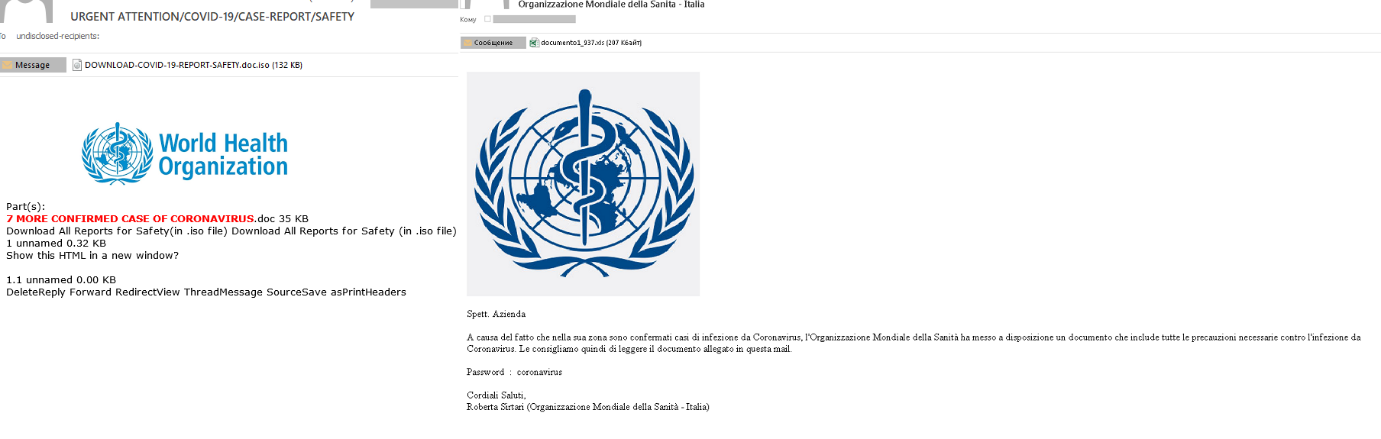

A fear of being infected with a new virus and a desire to know as much as possible about it could prompt recipients to review the email and open the links that it contained, as long as the message had been sent by a well-known organization. Fake letters from the WHO purporting to contain the latest safety advice were distributed in a variety of languages. The attachment contained files with various extensions. When the recipient tried to open these, malware was loaded onto the computer. In the message written in English, the attackers spread the Backdoor.Win32.Androm.tvmf, and in the one written in Italian, the Trojan-Downloader.MSOffice.Agent.gen.

Viral postal services

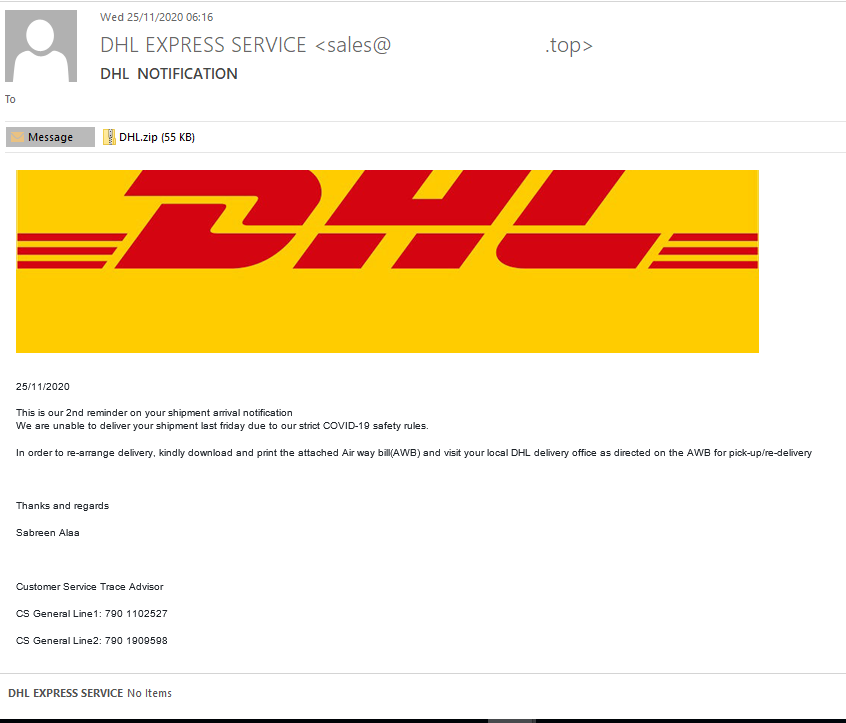

COVID-19 was also mentioned in fake email messages that mimicked notifications from delivery services. The sender said that there was a problem with delivering an order due to the pandemic, so the recipient needed to print out the attachment and take it to the nearest DHL office. The attached file contained a copy of the HEUR:Trojan.Java.Agent.gen.

The corporate sector

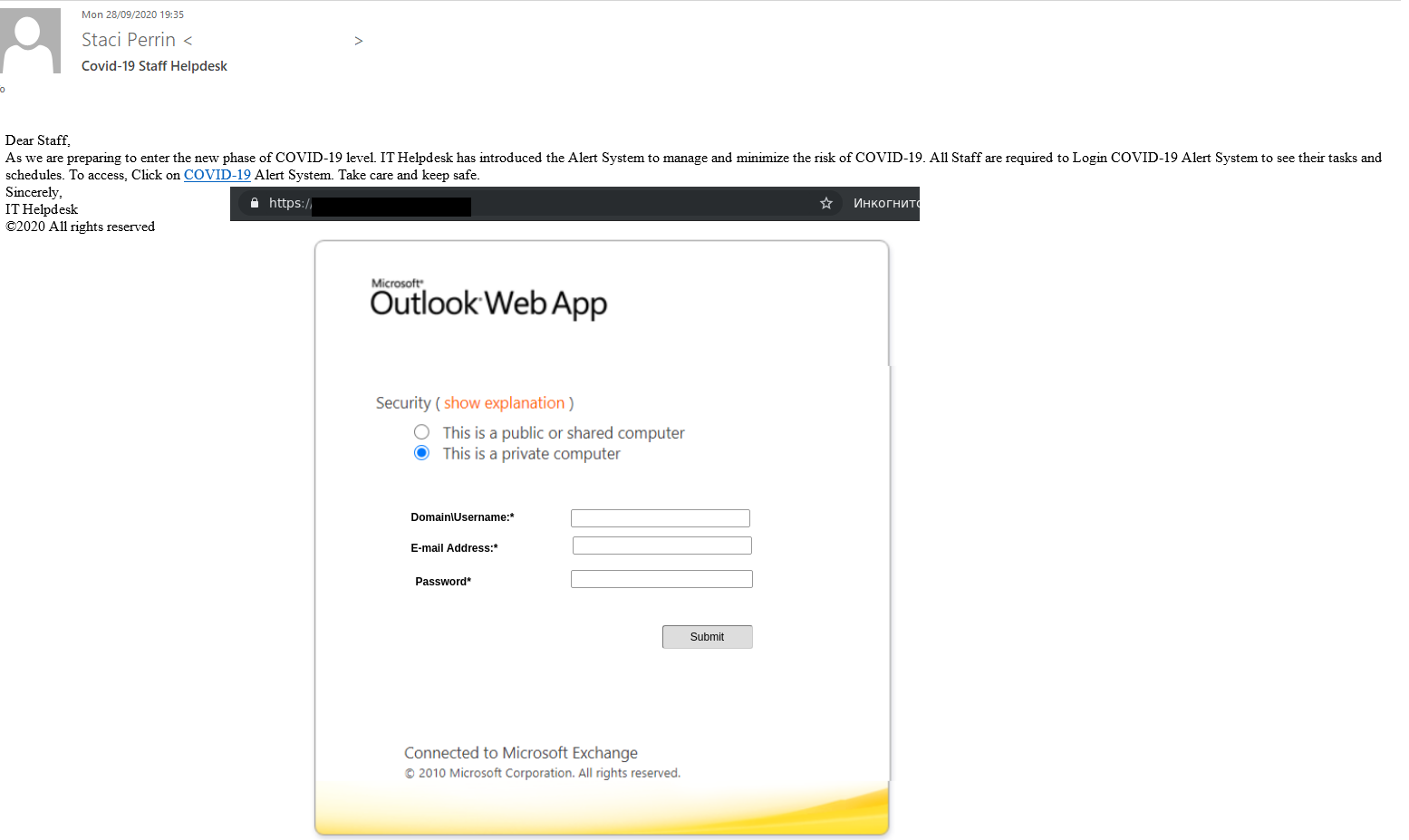

Spam that targeted companies also exploited the COVID-19 theme, but the cybercriminals occasionally relied on a different kind of tricks. For example, one of the emails stated that technical support had created a special alert system to minimize the risk of a new virus infection. All employees were required to log in to this system using their corporate account credentials and review their schedules and tasks. The link opened a phishing page disguised as the Outlook web interface.

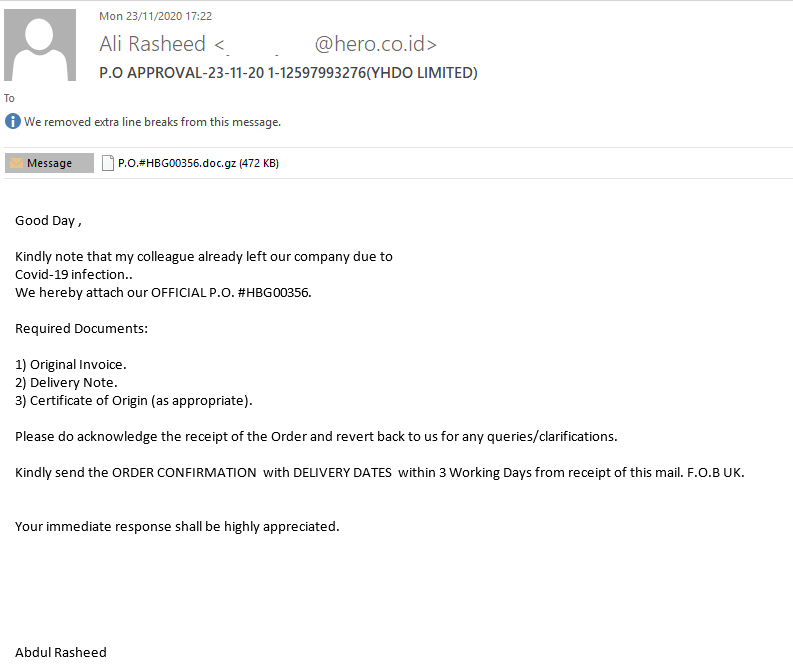

In another instance, scammers were sending copies of the HEUR:Trojan-PSW.MSIL.Agensla.gen in the form of an email attachment. The scammers explained that the recipient needed to open the attached file, because the previous employee, who was supposed to send the “documentation”, had quit over COVID-19, and the papers had to be processed within three days.

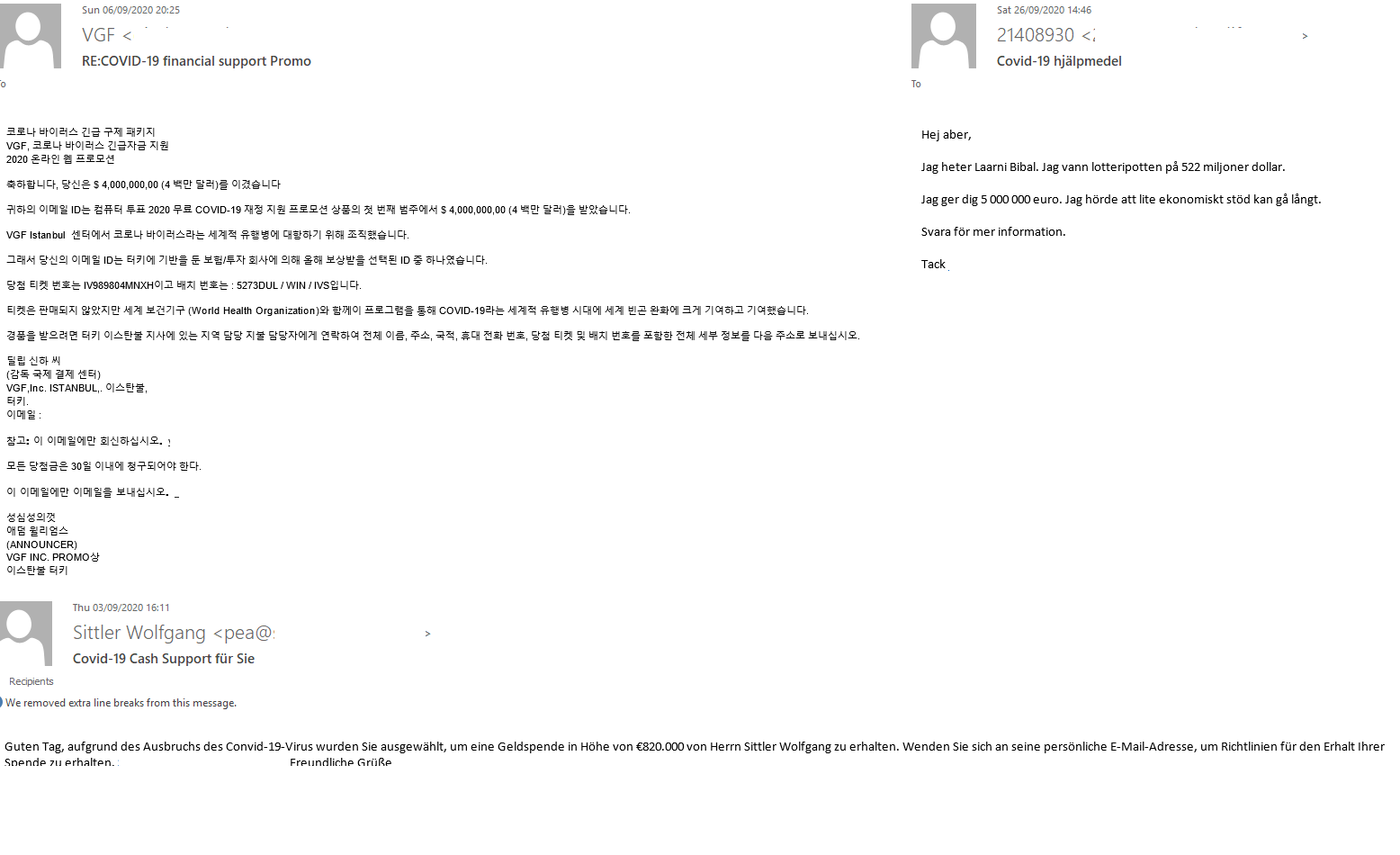

“Nigerian” crooks making money from the pandemic

Email from “Nigerian” scammers and fake notifications of surprise lottery winnings regularly tapped the pandemic theme. The message in Korean shown below says that the recipient’s email address had been selected randomly by some center in Istanbul for a coronavirus-related emergency payout. Such surprise notices of winnings and compensations were generally sent out in a variety of languages. Messages from some lucky individuals who had won a huge sum and wished to support their fellow creatures in the difficult times of the pandemic were another variation on the “Nigerian” scam.

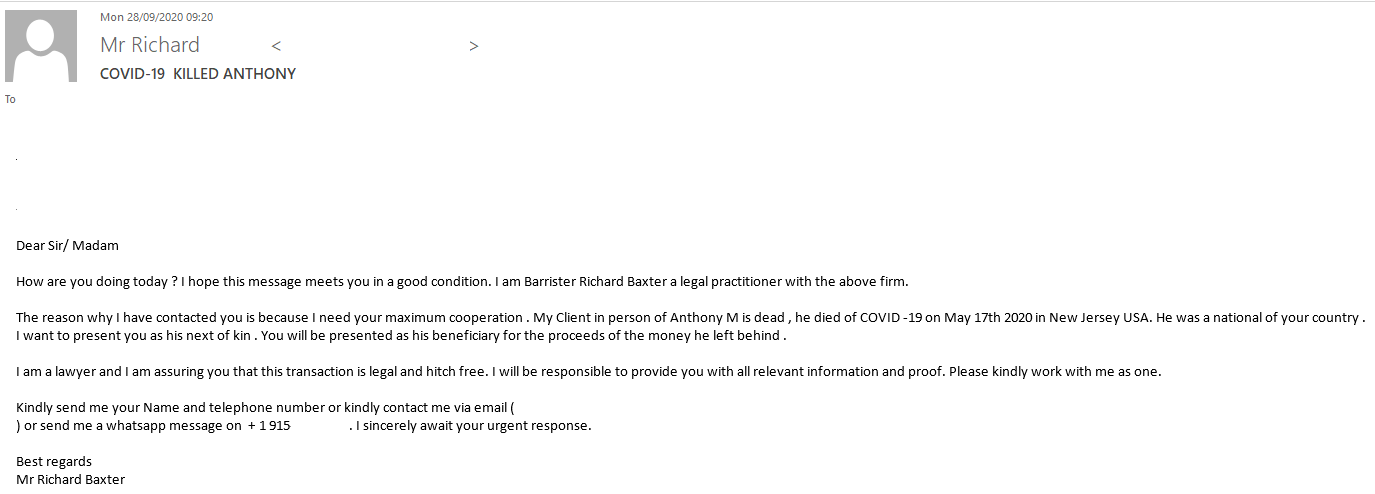

Where messages were signed as being from a lawyer trying to find a new owner for no-man’s capital, the sender emphasized that the late owner of the fortune had died of COVID-19.

An unusual turn of events

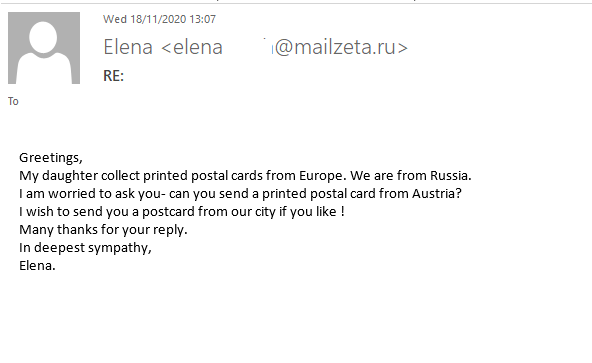

Regular “Nigerian” scam email is easy to recognize: it talks about millionaires or their relatives trying to inherit a huge fortune or bequeath it to someone who bears the same last name. The public seems to have become so accustomed to that type of junk mail that it has ceased to react, so cybercriminals have come up with a new cover story. To avoid being found out right away, they refrain from mentioning astronomical sums of money, instead posing as a mother from Russia who is asking for help with her daughter’s effort to collect postcards from around the world. The key point of this kind of messages is to get the potential victim to reply: the “mother’s” request sounds absolutely innocent and easy to do, so it can resonate with recipients. If the victim agrees to send a postcard, they are in for a lengthy email exchange with the scammers, who will offer them to partake in a large amount of money by paying a small upfront fee.

“Nigerian” scammers are not the only ones that have been getting creative. Spammers who sent out their messages through website feedback forms employed yet another unusual trick. The messages were signed as being from an outraged graphic artist or photographer, their names changing with each new message. The sender insisted that the website contained their works and thus violated their copyright, and demanded that the content be taken down immediately, threatening legal action.

The deadline for meeting the demand was quite tight, as the scammers needed the victim to open the link as soon as possible, while pondering on the consequences of that action as little as possible. A law-abiding site owner was likely to do just that. This is confirmed by related discussions in various blogs, with the users reporting that they immediately tried checking what photographs they had “stolen”. The links were not functional at the time the “complaints” were discovered, but in all likelihood, they had previously linked to malicious files or phishing programs.

Statistics: spam

Proportion of spam in email traffic

The share of spam in global email traffic in 2020 was down by 6.14 p.p. when compared to the previous reporting period, averaging 50.37%.

Proportion of spam in global email traffic, 2020 (download)

The percentage of junk mail gradually decreased over the year, with the highest figure (55.76%) recorded in January and the lowest (46.83%), in December. This may be due to the universal transition to remote work and a resulting increase in legitimate email traffic.

Sources of spam by country

The group of ten countries where the largest volumes of spam originated went through noticeable change in 2020. United States and China, which had shared first and second places (10.47% and 6.21%, respectively) in the previous three years, dropped to third and fourth. The “leader” was Russia, which was the source of 21.27% of all spam email in 2020. It was followed by Germany (10.97%), which was just 0.5 percentage points ahead of the United States.

Sources of spam by country in 2020 (download)

France gained 2.97 p.p. as compared to the year 2019, remaining fifth with 5.97%, while Brazil lost 1.76 p.p. and sunk to seventh place with 3.26%. The other countries in last year’s “top ten”, India, Vietnam, Turkey and Singapore, dropped out, giving way to the Netherlands (4.00%), which skipped to sixth place, Spain (2.66%), Japan (2.14%) and Poland (2.05%).

Malicious email attachments

Attacks blocked by the email antivirus in 2020 (download)

In 2020, our solutions detected 184,435,643 dangerous email attachments. The peak in malicious activity, 18,846,878 email attacks blocked, fell on March, while December was the quietest month, with 11,971,944 malicious attachments, as it was in 2019.

Malware families

TOP 10 malware families in 2020 (download)

Members of the Trojan.Win32.Agentb family were the most frequent (7.75%) malware spread by spammers. The family includes backdoors, capable of disrupting the functioning of a computer, and copying, modifying, locking or deleting data. The Trojan-PSW.MSIL.Agensla family was second with 7.70%. It includes malware that steals data stored by the browser, as well as credentials for FTP and email accounts.

Equation Editor vulnerability exploits, Exploit.MSOffice.CVE-2017-11882, dropped to third place with 6.55 percent. This family had topped the ranking of malware spread through spam in the previous two years.

Trojan.MSOffice.SAgent malicious documents dropped from second to fourth place with 3.41%. These contain a VBA script, which runs PowerShell to download other malware secretly.

In fifth place, with 2.66%, were Backdoor.Win32.Androm modular backdoors, which, too, are frequently utilized for delivering other malware to an infected system. These were followed by the Trojan.Win32.Badun family, with 2.34%. The Worm.Win32.WBVB worms, with 2.16%, were seventh. Two families, in eighth and ninth place, contain malware that carefully evades detection and analysis: Trojan.Win32.Kryptik trojans, with 2.02%, use obfuscation, anti-emulation and anti-debugging techniques, while Trojan.MSIL.Crypt trojans, with 1.91%, are heavily obfuscated or encrypted. The Trojan.Win32.ISO family, with 1.53%, rounds out the rankings.

TOP 10 malicious email attachments in 2020 (download)

The rankings of malicious attachments largely resemble those of malware families, but there are several subtle differences. Thus, our solutions detected the exploit that targeted the CVE-2017-11882 vulnerability more frequently (6.53%) than the most common member of the Agensla family (6.47%). The WBVB worm, with 1.93%, and the Kryptik trojan, with 1.97%, switched positions, too. Androm-family backdoors missed the “top ten” entirely, but the Trojan-Spy.MSIL.Noon.gen, with 1.36%, which was not represented in the families rankings, was tenth.

Countries targeted by malicious mailshots

Spain was the main target for malicious email campaigns in 2020, its share increasing by 5.03 p.p. to reach 8.48%. As a result of this, Germany, which had topped the rankings since 2015, dropped to second place with 7.28% and Russia, with 6.29%, to third.

Countries targeted by malicious mailshots in 2020 (download)

Italy’s share (5.45%) fell slightly, but that country remained in fourth place. Vietnam, which had previously rounded out the top three, dropped to fifth place with 5.20%, and the United Arab Emirates, with 4.46%, to sixth. Mexico, with 3.34%, rose from ninth to seventh place, followed by Brazil, with 3.33%. Turkey, with 2.91%, and Malaysia, with 2.46%, rounded out the rankings, while India, 2.34%, landed in eleventh place last year.

Statistics: phishing

In 2020, Anti-Phishing was able to block 434,898,635 attempts at redirecting users to phishing web pages. That is 32,289,484 fewer attempts than in 2019. A total of 13.21% of Kaspersky users were attacked worldwide, with 6,700,797 masks describing new phishing websites added to the system database.

Attack geography

In 2020, Brazil regained its leadership by number of Anti-Phishing detections, with 19.94% of users trying to open phishing links at least once.

Geography of phishing attacks in 2020 (download)

TOP 10 countries by number of attacked users

The countries with the largest numbers of attempts at opening phishing websites in 2018 “topped the rankings” again in 2020: Brazil, with 19.94%, in first place, and Portugal, with 19.73%, in second place. Both countries’ indicators dropped remarkably from 2019, Brazil “losing” 10.32 p.p. and Portugal, 5.9 p.p. France, which had not been seen among the ten “leaders” since 2015, was in third place with 17.90%.

Venezuela, last year’s “leader”, had the largest numbers in the first two quarters of 2020, but came out eighth overall, the share of attacked users in that country decreasing by 14.32 p.p. to 16.84%.

| Country | Share of attacked users (%)* |

| Brazil | 19.94 |

| Portugal | 19.73 |

| France | 17.90 |

| Tunisia | 17.62 |

| French Guiana | 17.60 |

| Qatar | 17.35 |

| Cameroon | 17.32 |

| Venezuela | 16.84 |

| Nepal | 16.72 |

| Australia | 16.59 |

* Share of users on whose devices Anti-Phishing was triggered out of all Kaspersky users in the country in 2020

Top-level domains

Most scam websites, 24.36% of the total number, had a .com domain name extension last year. Websites with a .ru extension were 22.24 p.p. behind with 2.12%. All other top-level domains in the “top ten” are various country-code TLDs: the Brazilian .com.br with 1.31% in third place, with Germany’s .de, (1.23%), and Great Britain’s .co.uk (1.20%) in fourth and fifth places, respectively. In sixth place was the Indian domain extension .in, with 1.10%, followed by France’s .fr with 1.08%, and Italy’s .it with 1.06%. Rounding out the rankings were the Dutch .nl, with 1.03%, and the Australian .com.au, with 1.02%.

Most frequent top-level domains for phishing pages in 2020 (download)

Organizations under attack

The rating of attacks by phishers on different organizations is based on detections by Kaspersky Lab’s Anti-Phishing deterministic component. The component detects all pages with phishing content that the user has tried to open by following a link in an email message or on the web, as long as links to these pages are present in the Kaspersky database.

Last year’s events affected the distribution of phishing attacks across the categories of targeted organizations. The three largest categories had remained unchanged for several years: banks, payment systems and global Internet portals. The year 2020 brought change. Online stores became the largest category with 18.12%, which may be linked to a growth in online orders due to pandemic-related restrictions. Global Internet portals remained the second-largest category at 15.94%, but their share dropped by 5.18 p.p. as compared to 2019, and banks were third with a “modest” 10.72%.

Online games and government and taxes dropped out of the “top ten” in 2020. They were replaced by delivery companies and financial services.

Distribution of organizations targeted by phishers, by category in 2020 (download)

Conclusion

With its pandemic and mass transition to remote work and online communication, last year was an unusual one, which was reflected in spam statistics. Attackers exploited the COVID-19 theme, invited victims to non-existent video conferences and insisted that their targets register with “new corporate services”. Given that the fight against the pandemic is not over yet, we can assume that the main trends of 2020 will stay relevant into the near future.

The general growing trend of targeted attacks on the corporate sector will continue into next year, all the more so because the remote work mode, increasingly popular, makes employees more vulnerable. Users of instant messaging networks should raise their guard, as the amount of spam and phishing messages received by their mobile devices is likely to grow as well. Besides, the number of email messages and schemes exploiting the COVID-19 theme one way or another has a high likelihood of rising.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh