2018-02-09 11:52:41 Author: parsiya.net(查看原文) 阅读量:131 收藏

I read the NISTIR 8202 - Blockchain Technology Overview draft so you do not have to. These are my notes from the January 2018 version of the document.

After reading this, you will know enough buzzwords to add Blockchain Expert to your LinkedIn title/Twitter bio/email signature.

You can find a copy of the draft at:

- Audience

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Blockchain Architecture

- 3. Blockchains in Operation

- 4. Consensus

- 5. Forking

- 6. Smart Contracts

- 7. Blockchain Categorization

- 8. Blockchain Platforms

- 9. Blockchain Limitations and Misconceptions

- 10. Conclusion

The publication is for somewhat technical readers that are not familiar with blockchain technology. It's not supposed to be a technical guide.

A blockchain is a distributed immutable digital ledger. The ledger can be private or public.

A wallet is used to sign transactions. Each wallet has at least one pair of public/private keys. Transactions signed by private keys can be verified using the public key. This means a user with access to the private key (not necessarily the wallet owner) has initiated the transaction.

When organizations want to use blockchains, they need to pay attention to:

- What if they need to modify the blockchain? Remember one prominent characteristic of blockchains is immutability.

- How do participants decide what transactions are valid? This is called reaching consensus.

Blockchains can store different values:

- Wealth: e.g. Bitcoin.

- Smart contracts: Software which is deployed on the blockchain and then executed by the participants.

From an accessibility perspective, blockchains can be:

- Permissionless: Anyone can participate/read/write.

- Permissioned: Not open to the public. Participants are vetted.

Most blockchains have the following core concepts:

- Each transaction is digitally signed and involves one or more participants accompanied by a record of what happened (e.g. amount of assets transferred).

- Blockchain is built from blocks where each block contains multiple transactions and some other information such as the hash of the previous block.

- Each new block's hash is stored in itself and in the next block.

A blockchain is a distributed immutable digital ledger usually without a central authority.

Concise description of blockchain technology:

Blockchains are distributed digital ledgers of cryptographically signed transactions that are grouped into blocks. Each block is cryptographically linked to the previous one after validation and undergoing a consensus decision. As new blocks are added, older blocks become more difficult to modify. New blocks are replicated across all copies of the ledger within the network, and any conflicts are resolved automatically using established rules.

1.1 Background and History

The current era of blockchains started with Satoshi Nakamoto's famous paper Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System. Satoshi is anonymous. The main benefit of Bitcoin over previous blockchains is enabling direct financial transfers between users.

Wallets are usually pseudonymous meaning the transactions can be tracked, but there's no real identity tied to a wallet. However, it's possible to track users when they cash out or via other means.

Another advantage of blockchains is enabling people to do business with unknown and untrusted users.

1.3 Notes on Terms

- User: Anyone who uses the blockchain.

- Node: Any system within the blockchain.

- Full node: Stores the complete blockchain.

- Mining/Minting node: Full node that also creates new blocks.

- Lightweight node: Does not store the complete blockchain or create new blocks and passes data to other nodes.

Blockchains use known cryptographic primitives and computer science concepts.

2.1 Hashes

Hash is a way of calculating a fixed sized output from any input. Output is usually called digest or message digest.

A good hashing algorithms has these characteristics:

- Diffusion: Smallest change in input results in a completely different output.

- Pre-image resistant: Hard to find input that results in a specific digest.

- Collision resistant: Hard to find two inputs that produce in the same digest.

- Second pre-image resistant: Hard to find any other input that produce the same digest as a specific input.

Bitcoin uses SHA-256. While it's theoretically possible to find collisions, it's almost impossible to have two valid blocks result in the same hash and be calculated close to each other in time.

If a single transaction/event in a block changes, hash of the block will completely change.

2.2 Transactions

A transaction is a recording of a transfer of assets. Each transaction usually has at least these components:

- Amount: Total amount of assets transferred.

- Inputs: "A list of digital assets to be transferred." Assets cannot be added or removed from digital assets, they have to be split into multiple new smaller assets. The other way is possible, smaller assets can be combined to make a larger assets.

- Parsia's note: This is wrong in my opinion. Input is a wallet with (hopefully adequate) digital assets. Later in the document we have Table 2 where Account A is listed under inputs.

- Outputs: Accounts/wallets that will receive the assets in the transaction.

- Transaction ID/Hash: Transaction's unique identifier.

Table 2: Example Transaction (taken directly from draft)

| Input | Output | Amount | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transaction ID: 0xa1b2c3 | Account A | Account B | 0.0321 | |

| Account C | 2.5000 | |||

| 2.5321 |

2.3 Asymmetric Key Cryptography

Asymmetric key cryptography usage in blockchains:

- Each wallet has at least one public/private key pair.

- Transactions are signed by private key.

- Public keys are used to derive addresses. They are usually hashed (with some other info) to produce the address. Multiple addresses can be derived from one public key.

- Public keys are used to verify transactions signed by private keys.

- Only the user with access to private key can sign valid transactions.

2.4 Addresses and Address Derivation

Address is a short, alphanumeric string derived from the user's public key usually through a hash function. Addresses are used in transactions (e.g. transferring money). Addresses are sometimes converted to QR codes for easier use.

2.4.1 Private Key Storage

Blockchains do not have any mechanism for storing private keys. Users usually use software or hardware wallets to store private keys. Private keys should be generated using a secure random function. The person with access to the private key, has full access to the account. Usually assets transferred after theft cannot be returned (blockchain is immutable). There are some noticeable exceptions such as Ethereum's hard fork.

2.5 Ledgers

Ledger is a collection of event/transactions.

Although it's in the best interest of the authority maintaining a centralized ledger, they have problems:

- Centralized ledgers can be lost or destroyed.

- Transactions might not be valid. Users must trust the authority to validate each transaction.

- Transaction lists might not be complete.

- Transactions might have been altered.

How distributed ledgers work (simplified):

- New transaction is submitted to node 1.

- Node 1 adds the transaction to its

transaction pool(or list of pending transactions).- There's no central repository of pending transactions, each node maintains its own.

- Node 1 sends the transactions to adjacent nodes. Adjacent nodes pass the new transaction around the network.

- Node 2 adds the transaction to a block and publishes it (e.g. mines the block).

- Node 2 sends the complete block to adjacent nodes.

- Other nodes verify the block, add it to their blockchains and pass it around. Each node removes any transactions that are in the newly mined block from its list and starts mining a new block.

2.6 Blocks

A block contains a list of validated transactions. "'Validity' is ensured by checking that the providers of funds in each transaction (listed in the transaction's 'input' values) have each cryptographically signed the transaction."

Parsia's note: I think there's a step missing here, nodes should also check if sender has enough assets for the transfer.

New transactions are added to the blockchain when a new block is published (by a node).

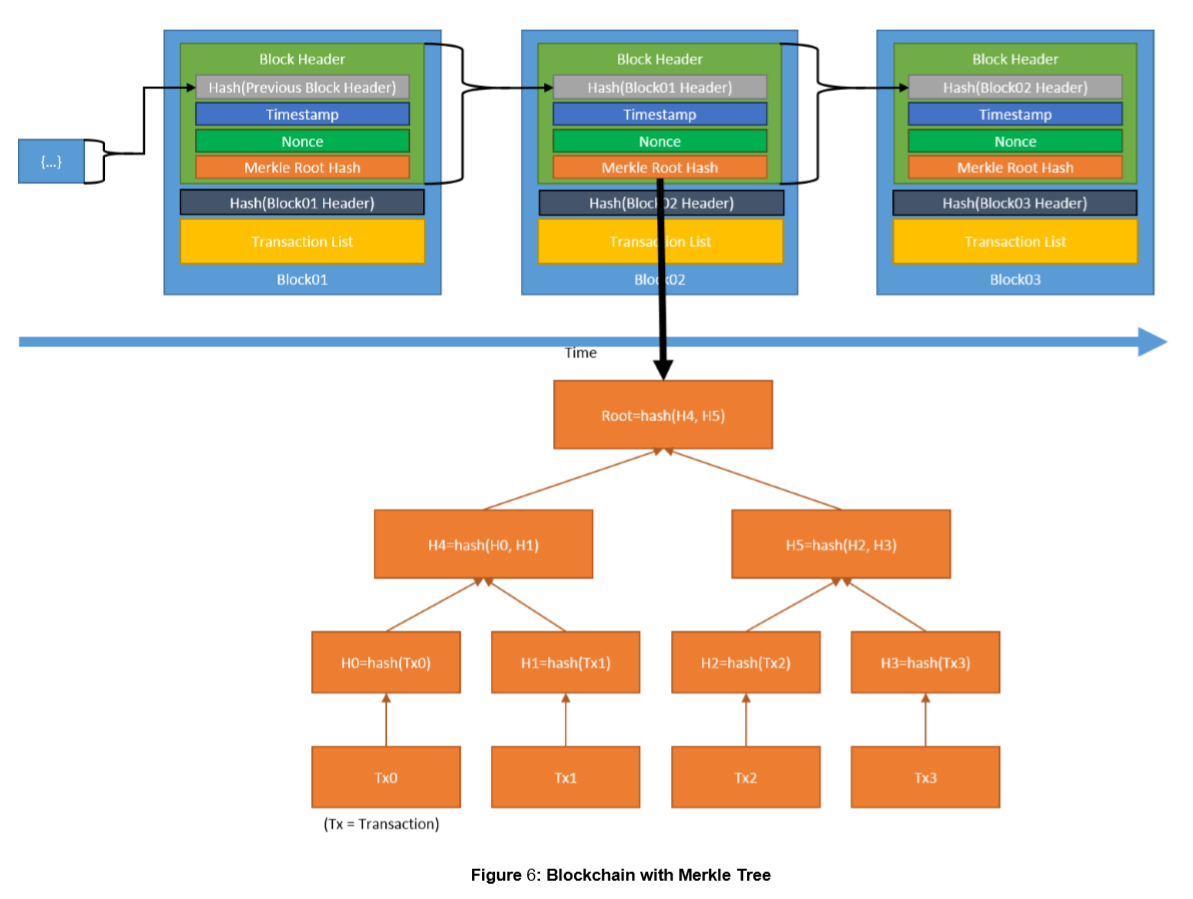

Each block usually consists of:

- Block number or block height.

- Current block's hash.

- Previous block's hash.

- Merkle tree root hash of transactions.

- Timestamp.

- Size of the block.

- Nonce value. Manipulated when mining.

- List of transactions.

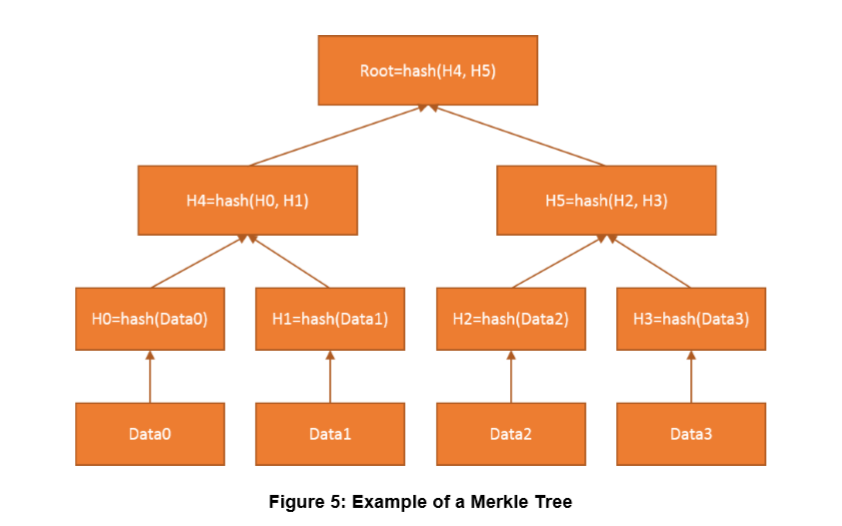

Merkle Tree Root Hash

Instead of hashing all transactions together, they are hashed in a binary tree.

- Level 0 of tree contains transactions.

- Level 1 is hash of each transaction (1:1).

- For each level, take two adjacent nodes and calculate their hash. Hash is sent to next level.

- Rinse and repeat until one hash remains.

Draft figure 5: Merkle Tree Root Hash

Draft figure 5: Merkle Tree Root Hash

Figures 5 and 6 are taken from the draft.

Entire block header is hashed and stored in the block (and in the next block). Right click and open the image in a new tab).

Draft figure 6: Blockchain with Merkle Tree

Draft figure 6: Blockchain with Merkle Tree

2.7 Chaining Blocks

Blocks are chained together:

- Each block has its own hash.

- Each block has hash of previous block.

- Each block's hash is stored in next block.

- Modifying any block will invalidated all block hashes after it in the blockchain and will be detected.

In this section a blockchain similar to Bitcoin is discussed. It's a permissionless blockchain that utilizes proof of work consensus method.

- Permissionless: Everyone can join the network.

- Proof of work: Because there's no central authority. Nodes need to perform a difficult task (mining a block) to be granted permission to create a new block and be rewarded (in this case bitcoins).

- Mining a block is a difficult task but verifying that a mined block is valid is easy.

Nodes

Nodes were briefly discussed in section 1.3, this is a more detailed discussion:

- Node: Any computer/system running blockchain software and participating in the network.

- Full Node:

- Store the entire blockchain.

- Pass data to other nodes.

- Check the validity of new blocks (see below for definition of validation).

- Propose new transactions.

- Mining Node (minting node):

- Full node.

- Maintain the blockchain by creating/mining new blocks.

- Lightweight Node:

- Do not store entire blockchain.

- Pass data to full nodes to be processed.

- Propose new transactions.

Validation

Validation means checking the following:

- Format of the new block.

- Hashes in the new block are correct (including hash of transactions and hash of entire block).

- New block has hash of previous block.

- Each transaction in the new block is valid and signed by correct parties (signed by private key(s) associated with the wallet).

New Transactions

Proposing a new transaction:

- Every node can propose new transactions.

- Each transaction is passed around the network.

- Mining nodes add proposed transactions to their unspent transaction pool.

- There's no central pool of unspent transactions.

- Each node maintains their own.

- When proposing a new transaction, sender can attach a transaction fee to it.

- Transaction fee: Reward for mining a block with the transaction thus validating it by adding it into the blockchain.

Candidate Block

Creating a candidate block (Parsia's note: candidate block is not defined in the draft, these are my own notes):

- Mining node selects some transactions from its unspent transaction pool to store into a new block before mining.

- There's no requirement or rule about choosing transactions.

- Pending transactions with attached transaction fees are processed first (more reward for the miner).

- Each transaction is checked for validity.

- Other nodes will reject blocks with invalid transactions.

- Mining node creates the block header (transaction hashes, previous block hash, timestamps, etc.).

- Now mining node has a candidate block.

Creating New Blocks

Mining a new block:

- Mining nodes start mining a new candidate block.

- Depending on the blockchain, mining nodes may need to perform some difficult work/puzzle to get to mine a new block.

- Blockchain's consensus method decides which node mines a new block.

Mining nodes in the blockchain are usually competing to mine new blocks. They do not trust each other.

A consensus model enables a group of mutually distrusting nodes to work together.

Genesis Block

First block of blockchain and often the only pre-configured block. The field for hash of the previous block is set to zero. Genesis block contains the initial state of the blockchain.

What Happens When a New Blockchain is Started

- Initial state of the blockchain is agreed upon (Genesis block).

- Nodes agree on a consensus method (how new blocks are added to the chain).

- Genesis block's previous block hash field is zero, for every other block this is calculated during mining.

- Users verify each new block.

4.1 Proof of Work Consensus Model

- Nodes compete in solving a difficult puzzle to earn the right to create the new block.

- Solving the puzzle is difficult, verifying the solution is easy.

- Difficult puzzle: Excessive use of energy.

- Nodes organize into pools to solve the puzzle through divide and conquer.

- In Bitcoin, mining nodes bruteforce the header nonce to find a block with a hash value lower than a certain number.

- Hash starting with certain number of zeros.

- This number is modified overtime to increase/decrease the difficulty of mining.

- This controls the publishing rate of new blocks.

- Past work on the puzzle does not influence solving future puzzles.

- After a block is published, everyone starts from zero and compete to mine the new block.

- If two blocks are mined roughly at the same time, the block with the largest chain is usually chosen. The network will wait and choose the chain that mines the next block first.

- This discourages nodes from discarding valid mining blocks by others (to only mine blocks themselves) because other nodes are already mining on top of the new block.

- But the majority of the nodes can conspire to discard valid blocks and only accept blocks mined by themselves.

- When a block is mined, it's sent to other nodes.

- Receiving nodes check the validity of the block (as mentioned before), add it to their block chain and pass it to other nodes.

4.2 Proof of Stake Consensus Model

- Nodes with more stake in the system want it to succeed.

- Nodes with more stake has a higher chance of being chosen to create new blocks.

- Stake is the amount of cryptocurrency that a node has in the system.

- How much node has bought into the blockchain.

- These blockchains use less energy because nodes do not have to solve puzzles.

- Usually nodes are not rewarded for creating new blocks.

Chain-Based Proof of Stake

- Choice of block creation is random.

- Nodes with higher stakes have a higher chance.

- Node with 20% of total stakes get chosen 20 times out of 100.

Byzantine Fault Tolerance Proof of Stake

Also called Multi-Round Voting System.

- Blockchain nominates several nodes.

- All staked users vote.

- After several rounds of voting, one node is chosen create mine a new block.

Coin-Age Proof of Stake

- Users spend "aged" cryptocurrency to create a new block.

- Coins need to be held for a certain duration before they can be spent (e.g. 30 days).

- When coins are spent, their age resets to zero.

- Users with more stake can create more blocks but cannot dominate the system.

4.3 Round-Robin Consensus Model

- Used in permissioned/private blockchain because there's a degree of trust between nodes.

- In permissionless blockchains, adversaries can add a large number of nodes and take control.

- Nodes take turns in creating new blocks.

- Model must have fall back procedures for unavailable nodes.

- Low power requirements, no need to mine/compete.

4.4 Ledger Conflicts and Resolutions

Or what to do when multiple valid blocks are published around the same time.

- Decentralized networks have lag.

- Multiple nodes may publish valid blocks and pass them to adjacent nodes.

- Results in multiple chains.

- Conflicts must be resolved quickly.

- Most blockchains let nodes mine and choose the chain that mines the next block first.

- Longest chain is chosen.

- Transactions in losing chain return to the unspent transaction pool and will be mined again.

Fork: Changes to the blockchain software and implementation.

5.1 Soft Fork

- Does not prevent users who do not adopt the change from using the modified blockchain.

- Must be accepted by majority of nodes to be adopted successfully.

- Example: Adding escrow and time-locked refunds to Bitcoin.

5.2 Hard Fork

- Locks out users who do not adopt the change.

- Changes to the hashing algorithm, consensus model or overhauling the protocol.

- Example: Ethereum hard fork after the DAO hack in 2016.

- Hard fork returned the stolen funds.

- Old fork renamed to Ethereum Classic.

- After each hard fork, users will have the same amount of assets in both the old and the new fork.

5.3 Cryptographic Changes and Forks

A hard fork is required if a vulnerability in the hash algorithm is discovered.

Some hashing algorithms:

- Bitcoin: SHA-256.

- Ethereum: Keccak-256.

- Litecoin: scrypt.

Post Quantum Blockchain

Table 3: Impact of quantum computing on common cryptographic algorithms (taken directly from draft).

| Cryptographic Algorithm | Type | Purpose | Impact from Large-Scale Quantum Computer |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES | Symmetric Key | Encryption | Larger key sizes needed |

| SHA-2, SHA-3 | N/A | Hash functions | Larger output needed |

| RSA | Public Key | Signatures, key establishment | No longer secure |

| ECDSA, ECDH (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) | Public Key | Signatures, key exchange | No longer secure |

| DSA (Finite Field Cryptography) | Public Key | Signatures, key exchange | No longer secure |

Parsia's small nitpick: Diffie-Hellman is a key agreement algorithm, parties do not exchange the key.

Parsia's note: This is a very bare section.

- A collection of code/function and data/state deployed to the blockchain.

- Contract executes the appropriate method with user input.

- Code is on the blockchain and immutable. If trusted, can be used by other users to perform actions.

- Store information.

- Perform calculations.

- Send funds to other parties.

- Similar to library functions in programming.

- Example: Publicly generate trustworthy random numbers.

- Leaderless Byzantine Paxos - Leslie Lamport

- https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/leaderless-byzantine-paxos/

- All mining nodes execute the smart contract code simultaneously when mining new blocks.

- Meaning smart contracts are more expensive than normal transactions.

- Submitting user attaches a fee to the smart contract for execution.

- If execution is longer than fee, execution will be aborted.

- Max limit on amount of time dedicated to execution of each smart contract to prevent malicious users from performing Denial of Service (DoS) attacks.

Based on permission model, blockchains can be:

- Permissionless: Open to the public. Everyone read/write/access.

- Permissioned: Users are vetted.

7.1 Permissioned

- Used by entities that trust each other to some extent but not completely.

- Can be readable by everyone but usually only certain users can write.

- Example: Laws, federal register.

- Laws: Everyone can read, only Congress nodes can publish.

- Federal register: Everyone can read, only federal government can publish.

- Users can verify the blocks and check the integrity/authenticity of laws/rules.

- Example: Laws, federal register.

- Everyone might be able to submit transactions but only certain users can read/write.

- Example: Voting. Everyone can vote but only voting machines read/record transactions.

- Consensus mechanism is based on how much users trust each other.

7.1.1 Application Considerations for Permissioned Blockchains

- How permissions are administered?

- Can write access be revoked?

- Who can create new blocks?

- Designate a trusted set of mining nodes.

- Tamper-evident design

- Prevent malicious nodes from submitting invalid transactions.

- How to handle invalid/malicious data on the blockchain?

- Undo theft.

- Blockchains are immutable by nature which makes this very difficult.

- Rewriting blocks is easier in permissioned blockchains.

- No need to solve difficult puzzles

- Mining nodes are incentivized to maintain the blockchain by out-of-band rewards (e.g. legal requirements).

7.1.2 Use Case Examples

Some use-cases. Parsia's Note: I think this section is the least important part of draft. Everyone can come of with "blockchain" ideas.

Banking

- Some banks come up with a private distributed ledger to record intra-bank transactions (e.g. SWIFT?).

- Only participating banks can see transactions.

- Use round-robin or Byzantine-Paxos to create blocks.

- Banks can agree to undo blocks if fraud occurs.

- Transactions are not anonymous.

Supply Chain

- Recording transfer of physical goods in the supply chain.

- Monitor supplier actions.

- Calculate and store warehouse stocks based on transactions.

Insurance and Healthcare

- Checking benefits.

- Insurance eligibility.

- Level of coverage.

- Medicine supply.

Parsia's note: What about challenges? For example handling PII, preventing HIPAA violations, confidentiality of patient data.

We can also talk about examples such as:

- Software supply chain management with blockchain? CCleaner malware example?.

7.2 Permissionless

- Most common. Most cryptocurrencies are permissionless.

- No central authority.

- Everyone can participate.

- Non-trivial proof of work consensus model (e.g. mining).

7.2.1 Application Considerations for Permissionless Blockchains

- Public facing data:

- Blockchain is public.

- What should be stored?

- How to protect privacy of users?

- Full transactional history:

- Everyone can read all transactions.

- False data attempts:

- Everyone can participate so malicious users are present.

- How to prevent invalid transactions?

- Data immutability:

- Applications usually follow CRUD (Crete, Read, Update, Delete) but blockchains only have CR (Create, Read).

- How to deprecate older events when they are updated?

- How to handle invalid/outdated data?

- Transactional throughput capacity:

- Proof of work is needed so new blocks are added slowly (e.g. Bitcoin blockchain can only confirm X transactions per second).

- How to handle unconfirmed transactions waiting in queue?

- Transaction fees incentivizes mining nodes.

7.2.2 Use Case Examples

Use-case examples for permissionless blockchains.

Trusted Timestamping

- Users upload data.

- Hash of data and timestamp is added to blockchain.

- Users can prove access to data at a certain time by hashing the data and comparing with the data on the blockchain.

- Patents.

- Contract signatures.

Parsia's note: This is a good tutorial application.

Energy Industry

- Store energy certificates in the blockchain.

- Which user has produced and how much.

This section is a short overview of different blockchain platforms currently in use.

8.1 Cryptocurrencies

Perhaps the most popular blockchains.

8.1.1 Bitcoin (BTC)

- The OG cryptocurrency.

- SHA-256 hash.

- Proof of work system where miners need to find a nonce value that creates a block hash smaller than a certain number (e.g. start with a certain number of zeros).

- Difficulty is adjusted to have a new block every 10 minutes.

- Mining nodes get Bitcoins for each new block.

- Transaction fees are optional but needed as time goes on:

- Block rewards decrease as time passes by (and eventually reach zero).

- Blockchain can only process a certain number of transactions per second and there's a backlog of unconfirmed transactions.

- Transactions contain code written in

Script.- Bitcoin transactions only a small subset of it.

- Not Turing complete.

8.1.2 Bitcoin Cash (BCC)

Parsia's note: Depending on the exchange, BCC could mean BitConnect Coin. Bitcoin Cash is BCH in some exchanges.

- Created when original Bitcoin blockchain had a hard fork in July 2017 after introduction of Segwit.

- Segregated Witness (Segwit) splits transactions into two segments: transactional data and signature data.

- Reduced the amount of data that need to be verified in each block thus increasing speed.

8.1.3 Litecoin (LTC)

- Similar to Bitcoin.

- Implemented Segwit and has a larger block size.

- Witness signature is separated from Merkle tree.

- Uses scrypt for hashing.

8.1.4 Ethereum (ETH)

- Focused on providing smart contracts.

- Ethereum's transaction programming language is Turing complete.

- Mining nodes receive funds through mining and transaction fees.

- Transactions must be accompanied by transaction fees.

- Gas: 1/100,000 Ether.

- Transactions consume gas.

- If transactions do not have sufficient gas, they are aborted.

- Max gas for each transaction is 3 million (30 Ethers).

- All mining nodes must execute transactions in parallel.

- Result of transaction is recorded in next block.

8.1.5 Ethereum Classic (ETC)

- Hard fork of ETH.

- Created when ETH rewrote history after the DAO hack.

- Some users rejected the fork for philosophical reasons.

- Almost everything else is the same as ETH.

8.1.6 Dash (DASH)

- Wants to provide faster transactions.

- Makes transactions in four seconds.

- Hash a "masternode" network.

- A deterministic order of masternodes by using hash and proof of work.

- Masternodes need 1000 Dash collateral.

- Uses all 11 SHA-3 contestant candidates in a chain.

- Harder to produce ASICs for mining.

- Harder mining.

8.1.7 Ripple (XRP)

- Name of both cryptocurrency and payment network.

- Fixed supply of 100 billion XRPs. Half for circulation.

- Clients do not need full blockchain.

- No mining rewards.

- Each transaction destroys a specific amount of currency.

8.2 Hyperledger

- Linux Foundation.

- Several projects.

- https://github.com/hyperledger

8.2.1 Hyperledger Fabric

- Modular blockchain.

- Has smart contracts named Chaincode (in Golang).

- Written in Golang.

- https://github.com/hyperledger/fabric

8.2.2 Hyperledger Sawtooth

- Modular blockchain.

- Proof of elapsed time as consensus protocol.

- Each node asks for a wait time from a hardware enclave.

- Hardware enclave returns a random number for each request.

- The node with smallest wait time mines the next block.

- Tied to hardware that can provide the enclave.

- https://github.com/hyperledger/sawtooth-core

8.2.3 Hyperledger Iroha

- Identity service based on blockchain.

- Institutions can manage identities.

- https://github.com/hyperledger/iroha

8.2.4 Hyperledger Burrow

- Permissioned blockchain.

- Accepts Ethereum smart contracts.

- https://github.com/hyperledger/burrow

8.2.5 Hyperledger Indy

- Independent identity platform.

- Users can exchange verifiable claims.

- Has three privacy features:

- Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs).

- Pointers to off-ledger sources (no personal data in blockchain).

- Zero-knowledge-proofs.

- https://www.hyperledger.org/projects/hyperledger-indy

8.3 MultiChain

- Allows users to setup, configure and deploy blockchains.

- Fork of Bitcoin with modifications.

- Default configuration: private, permissioned using round-robin consensus.

- https://github.com/MultiChain

This section talks about some limitations and mistakes about blockchain

9.1 Blockchain Control

- Even permissionless blockchains still depend on core developers of software that runs on nodes.

- Even when developers mean well, they can still introduce vulnerabilities into the system.

9.2 Malicious Users

- Blockchain system can control transaction rules and specifications.

- It cannot enforce a code of conduct.

- Any permissionless blockchain has malicious users.

- Blockchains often use monetary rewards (cryptocurrency for mining new blocks) to motivate users to act fairly.

- Once malicious users control a decent number of nodes, they can:

- Ignore transactions.

- Create their own altered version of blockchain and then revealing it when it's longer than the current blockchain. Honest nodes will switch to the longer chain and all transactions in the old blockchain are invalidated.

- Refuse to transmit blocks to other nodes.

- Ignore mined blocks from other nodes and only accepting their own.

- Blockchains can do hard forks to combat malicious users with a majority.

9.3 No Trust

- Users in permissionless blockchains do not trust each other.

- In every blockchain system, users need to have trust:

- Trust in the cryptographic primitives (e.g. hash function is collision-resistant).

- Trust in the software developers to write bug-free code and not intentionally introduce vulnerabilities.

- Trust that majority of users are not colluding in secret.

- Trust that nodes are accepting and processing transactions fairly.

9.4 Resource Usage

- Blockchains based on Proof of Work Consensus Model (e.g. Bitcoin), use a lot of energy and resources to solve difficult puzzles.

- Every new full node that joins the network needs to download the complete blockchain (over 100 GB for Bitcoin).

- Blockchains have limits on amount of data stored and are not meant to be storage options. Using a blockchain as a storage medium will be slow and consume many resources.

- Usually pointers to off-site data and hashes are stored on the blockchain with some other metadata.

9.5 Transfer of Burden of Credential Storage to Users

- No built-in user key management.

- If private keys are lost, account is lost.

- If private keys are stolen, then account belongs to the thief.

- No "Forgot my Password" functionality.

9.6 Private/Public Key Infrastructure and Identity

- Nodes verify that transactions are signed by private key associated with an account but they do not provide any means of associating real-world identities to accounts.

- Wallets are not anonymous and can be tracked. Usually it's possible to discover the identity of user associated with wallet through exchanges or anywhere digital assets are converted to real-work currency.

- Typical blockchains are not designed to be identity management systems.

I have skipped this section. Very similar to executive summary.

Parsia's note: I will provide my feedback to draft authors. Hopefully it can help make the document more useful. If you have any feedback please let me know.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh