2021-05-01 06:20:40 Author: parsiya.net(查看原文) 阅读量:261 收藏

Recently, I looked at the NordPass Password Manager browser extension. I could not find any guides on manual testing of browser extensions. I decided to write my own. So, here we are, "pushing the boundaries of science."

List of things I think you will learn after reading this post. This helps you decide if you want to spent time reading or not.

- Quick recon on a browser extension and desktop app combo.

- Local servers.

- Analyze traffic between the extension and the app.

- Discover the tech stack of the applications.

- Test browser extensions.

- Load unpacked extension in Edge.

- Modify the extension source to make it easier to read/debug.

- Reverse engineer obfuscated JavaScript with VS Code.

- Find open source sections of code.

- Identify and reverse engineer custom application code.

- Log and instrument extensions.

- JavaScript cryptography with SubtleCrypto.

- Bonus: Why 96 bits is the ideal IV size for AES-GCM.

- Dynamic analysis of JavaScript code with DevTools.

- Console.

- Snippets.

- Export extension's functions for manual fuzzing.

- Call function's in the extension without debugging.

- Windows 10 VM.

- Microsoft Edge (should work on Chrome, too).

- Comes with the VM.

- Free Nord account.

- Nordpass Password Manager desktop application.

- I am using version

2.33.14but this should work on any recent version.

- I am using version

- Wireshark and npcap.

- Visual Studio Code.

Install the Nordpass desktop application and start it. The Windows firewall dialog might appear because the current version of the Nordpass desktop is listening on all interfaces. This might be fixed by the time you read this.

The Local Server

Open an admin command prompt and run netstat -anb > c:/path/to/some/file. Open

the file and search for nord.

TCP 0.0.0.0:9213 0.0.0.0:0 LISTENING

[NordPass.exe]

TCP [::]:9213 [::]:0 LISTENING

[NordPass.exe]The b switch puts the process name on a separate line so,

netstat -anb | findstr /spin "nordpass" is useless for this output.

$ netstat -anb | findstr /spin "nordpass"

16: [NordPass.exe]

51: [nordpass-background-app.exe]

53: [nordpass-background-app.exe]

62: [NordPass.exe]First Issue: Thse server is listening on all interfaces. It should not.

People from outside might be able to connect to the server. In the real world,

this is less scarier than it sounds because in most personal networks the

router/modem only allows connections from other machines on the local network

and not from the outside.

The Desktop Application

The desktop app is installed in %LocalAppData%\Programs\nordpass. A brief look

at the installation directory tells us it's an Electron app (there's a file

named LICENSE.electron.txt lol).

The source for an Electron app is in resources\app.asar. We can extract it by

running the asar command (install with npm):

asar e app.asar c:/projects/nordpass/app.asar.original.

Note the resources\app.asar.unpacked directory. If you copy the app.asar

file to a different path and try to extract it you will get an error. The

app.asar file references this directory and the extraction does not work if it

is not present.

Note: Closing the Nordpass app just minimizes it to tray. Right-click on the tray icon and select quit to properly close it.

The Background Application

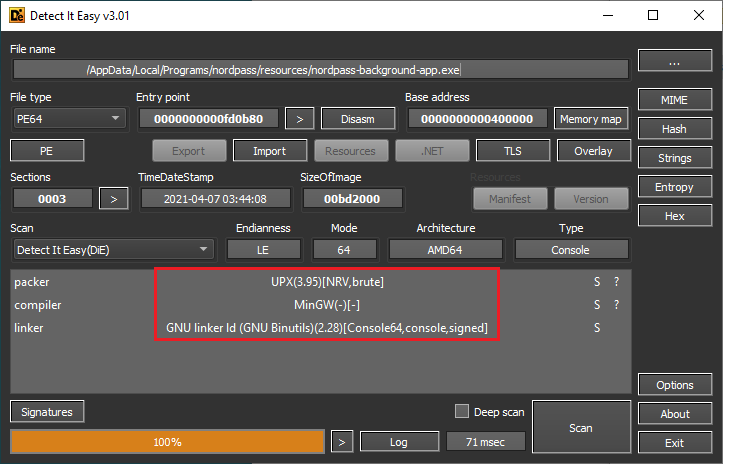

The background app is at resources\nordpass-background-app.exe. It's a

compiled binary. Analyze it with Detect-It-Easy to see it's packed

with UPX.

Detect-It-Easy results for the background app

Detect-It-Easy results for the background app

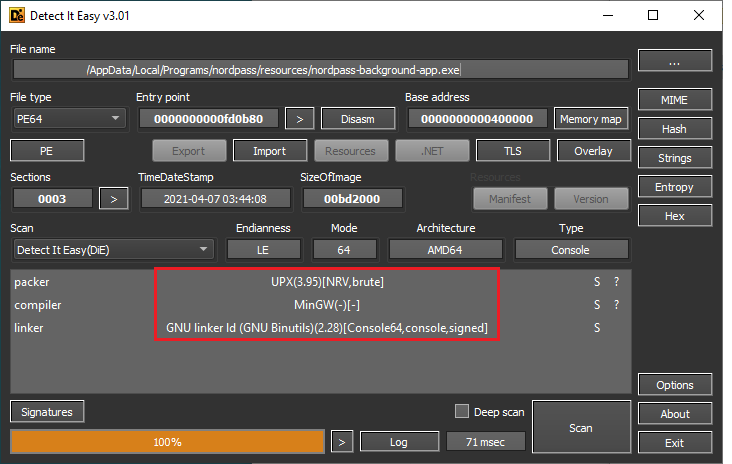

We can also open it with 7-Zip to see the UPX sections.

Background app opened in 7-zip

Background app opened in 7-zip

It's actually a Go app.

$ strings -n 10 nordpass-background-app.exe | findstr "Go"

Go build ID:There are a few analysis tools like ElevenPaths' Neto or Duo's crxcavator for browser extensions. I could not find anything about manual testing so, I wrote my own.

Setting Up The Extension

Start Wireshark and listen on the loopback interfaces. It's

Adapter for loopback traffic capture (installed by npcap). Use filter

tcp.port == 9213.

Go to the extension web page in Edge. You will see a prompt about allowing other stores. This lets Edge install extensions from the Chrome web store.

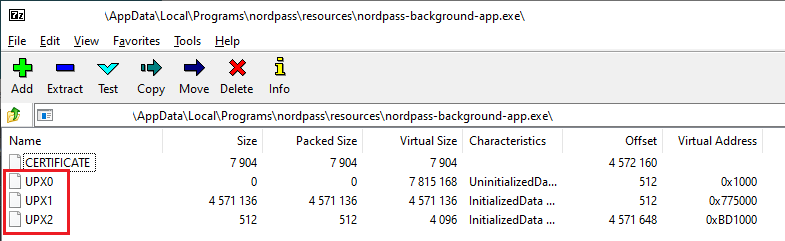

After installing the extension (if the desktop app is running), it will show a

four-digit code. The desktop app will display a window where you can enter it.

This pairs the extension with the app. Let's call this the pairing code.

Pairing the extension

Pairing the extension

The Old New Thing - Yet Another Local WebSocket Server

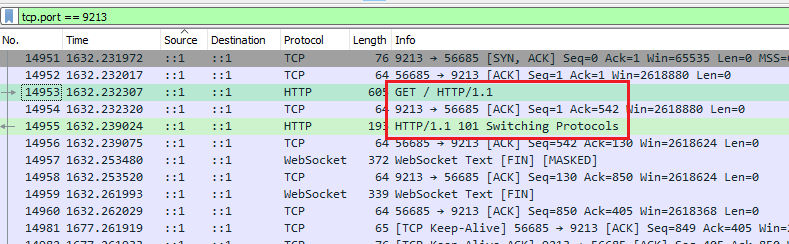

Switch to Wireshark and see the Switching Protocols text. It's the handshake

request of a WebSocket connection.

Pairing traffic in Wireshark

Pairing traffic in Wireshark

Right-click the handshake in Wireshark > Follow > HTTP Stream (some misc

headers removed):

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:9213

Connection: Upgrade

Upgrade: websocket

Origin: chrome-extension://fooolghllnmhmmndgjiamiiodkpenpbb

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

Sec-WebSocket-Key: AR0a/AoK76S/znNsjVC8KQ==

Sec-WebSocket-Extensions: permessage-deflate; client_max_window_bits

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: SfGJJieKb0arlzTiMRAhTszBanA=The Origin header shows this is coming from the extension. This is a

cross-origin request (chrome-extesion://... to http://localhost:9213).

But, Parsia, we do not see the Access-Control-Allow-Origin response header,

CORS is not enabled. The extension cannot see this response!!1!

Well, didja know?

Well, didja know?

Optional reading assignments:

- Read the so-called PlayStation Now RCE report. The root cause was a similar local WebSocket server.

- Read The Same-Origin Policy Gone Wild by yours truly for some curious SOP edge cases.

- (optional) Watch my presentation localghost: Escaping the Browser Sandbox Without 0-Days for some "thought leadership."

The traffic is over HTTP which is not really that bad. Before you scream HTTPs

let's enumerate their options for deploying a TLS server with a valid

certificate.

- Generate a self-signed certificate and add it to the OS key store.

- No one like this, see Superfish.

- Use a valid certificate for

localhost. Assuming you can convince someone to sign it.- Boo! You just gave everyone a valid cert for localhost.

The Messaging Protocol

Each message is a JSON object.

The first message after installation from the extension to the server:

{

"id": 1,

"type": "EXTENSION/LOGIN",

"key": "ea3b758623d2cfc13b1957...", // long hex value

"isFullScreen": false,

"extensionId": "fdrk45blr",

"browser": "edge"

}The server replies with a similar message:

{

"id": 1,

"type": "EXTENSION/LOGIN",

"key": "006e36c4dda85cce40711f49", // long hex value

"isDesktopLaunchedOnSameUser": true

}We have no idea what these are. Converting the hex values to ASCII does not give us anything.

Next, the extension displays the four-digit code. After entering it in the desktop app we see encrypted messages.

ext -> srv

{

"id": 2,

"data": "7919c0de7a34f60936145940dea3b758623d2cfc13b195739b1171adaa13..."

}

srv -> ext

{

"id": 2,

"data": "64b5b7b9006e36c4dda85cce40711f49d6e830e2e50b1c483421cabdbc4b..."

}After the first installation, we will not see the handshake again. We just see encrypted messages.

Debugging The Extension

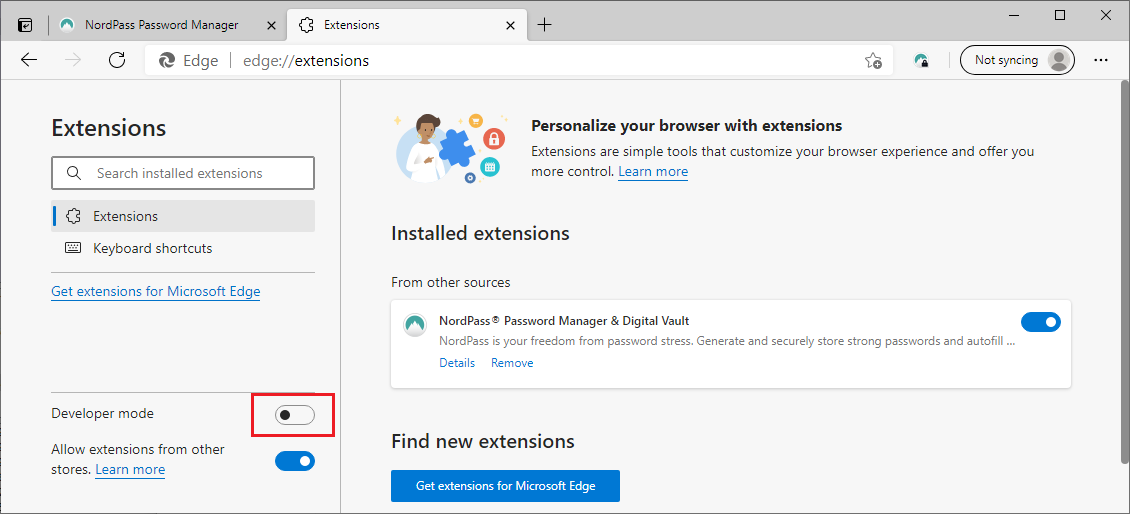

In Edge, go to edge://extensions. Enable Developer mode with the slider in

the bottom left of the page.

Edge extension developer mode

Edge extension developer mode

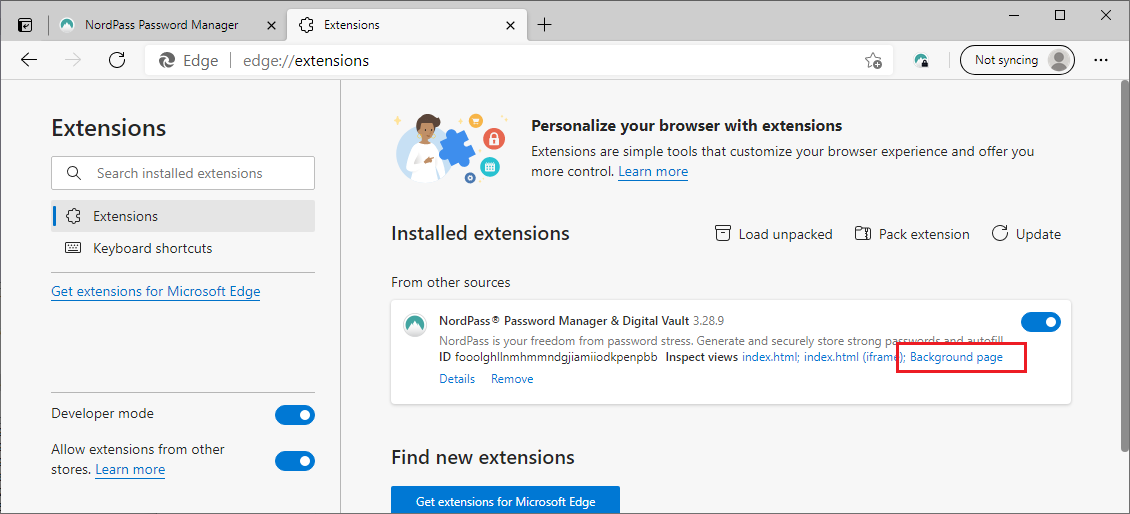

Now, we can click on the different active extension pages and debug them with DevTools.

After developer mode is enabled

After developer mode is enabled

We are interested in the background page.

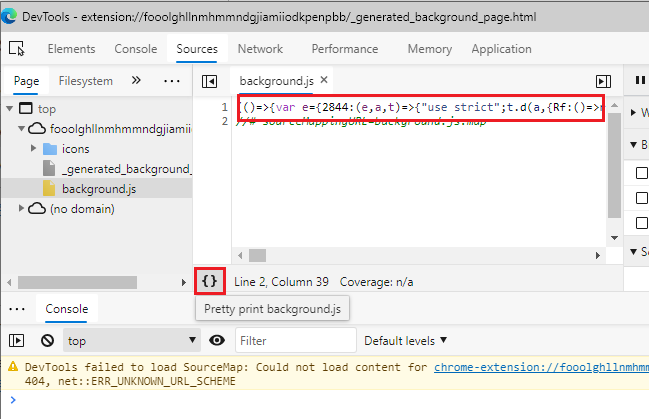

Background page in DevTools

Background page in DevTools

The extension's JavaScript is minified and painful to debug. We can click on the

{} button to beautify the code here. Let's do better.

Loading Unpacked Extensions

On Windows, Edge extensions are stored at

%userprofile%\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Extensions\.

Our extension is in

fooolghllnmhmmndgjiamiiodkpenpbb (this is the extension's ID in the Chrome web

store). Copy this directory to another path. We will modify this.

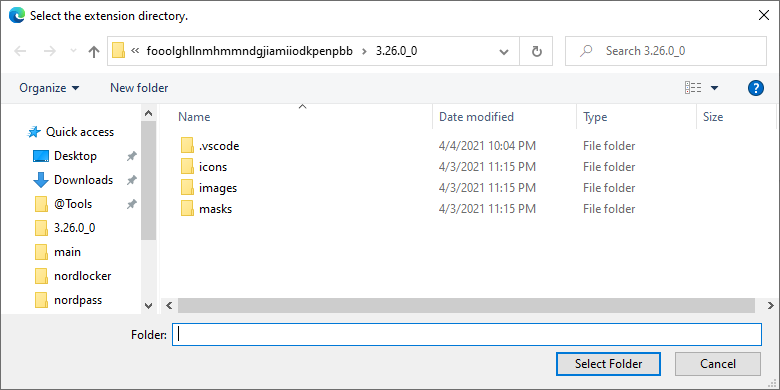

In edge://extensions remove the original extension. Next, click on the

Load unpacked button. Select the fooolghllnmhmmndgjiamiiodkpenpbb\3.26.0_0

directory. When loading an unpacked extension you should select the path with

the manifest.json file. Parent directories do not work.

Extension directory

Extension directory

Using our copy as an unpacked extension means we can directly modify the source and reload the extension to see the changes.

Beautifying JavaScript

There are multiple online services like CyberChef to beautify JavaScript. I use a local Python (also node) module named js-beautify.

$ cd fooolghllnmhmmndgjiamiiodkpenpbb\3.26.0_0

$ js-beautify -r *.js

beautified redirectContent.js

beautified app.js

beautified background.js

beautified content.js

beautified autofill.js

beautified analytics.jsReload the extension (click the reload link in edge://extensions) and we

should see beautified JavaScript in DevTools.

Beautified Extension

Beautified Extension

We can set breakpoints and debug the extension but we are still dealing with obfuscated JavaScript.

By now, you are wondering why we manually beautified the extension instead of letting the browser do it for us. I want to use VS Code's rename symbol ability to reverse engineer the extension's code.

Right-click on the extension directory and open it in VS Code. Open

background.js. Click on any variable (some times you have wait 10-20 seconds

for the editor to parse the file) and press F2. Choose a new name and it will

be renamed every where.

Renaming Symbols With VS Code Rename

To be fair JavaScript scope is a mess and doubly so for obfuscated code.

- Does not check if there is an existing variable with the same name in scope.

- Has some issues with the scope of parameters for inline functions so be

careful when renaming

efunction parameters. - The editor reparses the whole file after every save. Do multiple changes before saving to speed things up. This has been hit-and-miss, sometimes it's super quick and sometimes not.

- If VS Code is taking too long to parse the file, close it and open it again.

Most important tip: Create a backup every time you reload the extension and it still works. Sometimes, the refactor messes up the JavaScript and you want a working copy with most of your progress. I use git and create a commit after every few renames. If things go bad, revert.

Reversing Workflow

- Debug the extension, add some breakpoints, etc..

- Rename some variables (or add comments).

- In

edge://extensionsclickReloadin front of the extension. - The extension will be reloaded but your DevTools page is not closed and the breakpoints are not cleared. The breakpoints even persist after you close Edge.

- If the extension is still working and there are no errors, create a backup

(

git commit). - If something is broken, spend a few minutes to fix it but I usually

git resetto a good state instead. - Go to 1.

I have found a few online tools that help with deobfuscating JavaScript.

- JS Nice: http://jsnice.org/

- JStillery: https://mindedsecurity.github.io/jstillery/

- de4js: https://lelinhtinh.github.io/de4js/

I have not gotten great results from them. E.g., JS Nice has trouble parsing

big obfuscate blobs and its output is not valid JavaScript most of the time. I

have had a little success pasting individual functions or modules.

There are two types of code in such files:

- Open source modules.

- Application code.

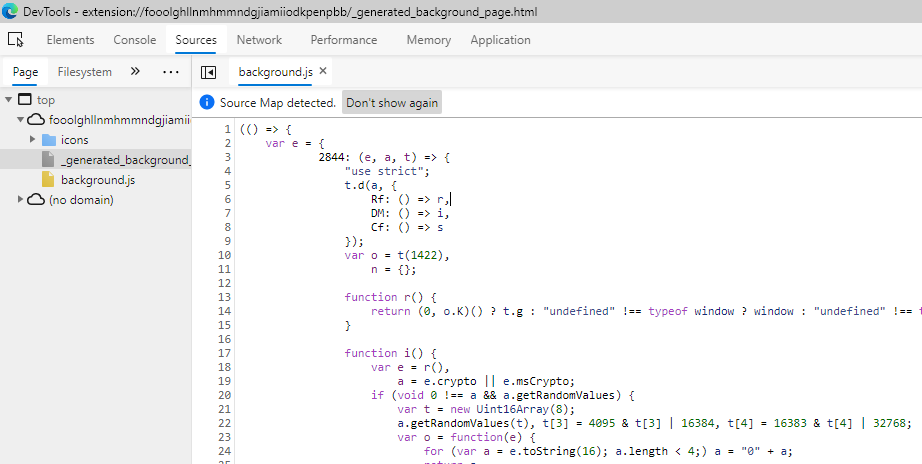

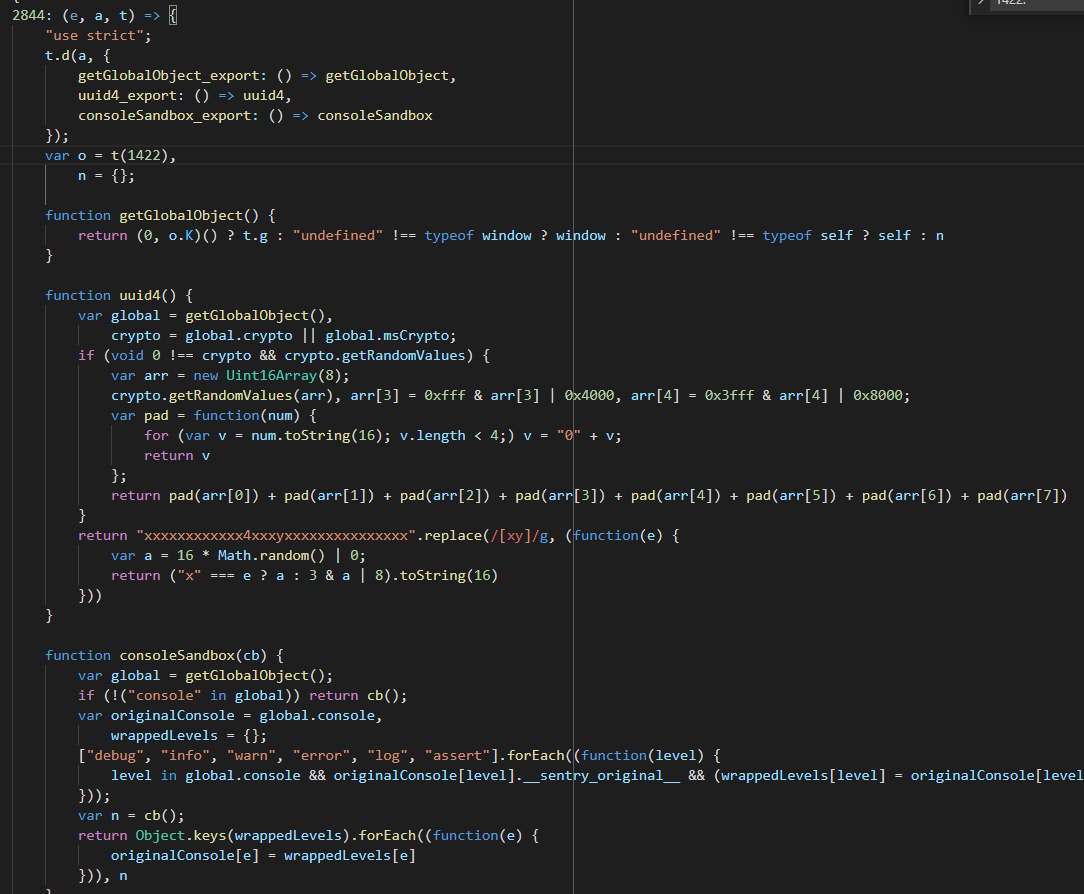

Reversing Open Source Code

I have learned some things about these kinds of files by trial and error. E.g.,

number: is the start of a module. This is the first module in background.js:

(() => {

var e = {

2844: (e, a, t) => {

"use strict";

t.d(a, {

Rf: () => r,

DM: () => i,

Cf: () => s

});

var o = t(1422),

n = {};

function r() {

return (0, o.K)() ? t.g : "undefined" !== typeof window ? window : "undefined" !== typeof self ? self : n

}

function i() {

var e = r(),

a = e.crypto || e.msCrypto;

if (void 0 !== a && a.getRandomValues) {

var t = new Uint16Array(8);

a.getRandomValues(t), t[3] = 4095 & t[3] | 16384, t[4] = 16383 & t[4] | 32768;

var o = function(e) {

for (var a = e.toString(16); a.length < 4;) a = "0" + a;

return a

};

return o(t[0]) + o(t[1]) + o(t[2]) + o(t[3]) + o(t[4]) + o(t[5]) + o(t[6]) + o(t[7])

}

return "xxxxxxxxxxxx4xxxyxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx".replace(/[xy]/g, (function(e) {

var a = 16 * Math.random() | 0;

return ("x" === e ? a : 3 & a | 8).toString(16)

}))

}

function s(e) {

var a = r();

if (!("console" in a)) return e();

var t = a.console,

o = {};

["debug", "info", "warn", "error", "log", "assert"].forEach((function(e) {

e in a.console && t[e].__sentry_original__ && (o[e] = t[e], t[e] = t[e].__sentry_original__)

}));

var n = e();

return Object.keys(o).forEach((function(e) {

t[e] = o[e]

})), n

}

},

Usually modules are imported by others. Search for 2844 to see where it's

imported:

1170: (e, a, t) => {

"use strict";

t.d(a, {

yW: () => c

});

var o = t(2844), // t is `require`.

Most of the code is usually open source modules. We can find them with a bit of

searching. This module has a unique string

(xxxxxxxxxxxx4xxxyxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx). We can use grep.app to

search it on GitHub.

It's a JavaScript UUID generator. I could not easily find the actual module for

it. Usually, it's easier than that. Wait, there's the sentry_original word in

the original code. It might be the sentry SDK (3rd result).

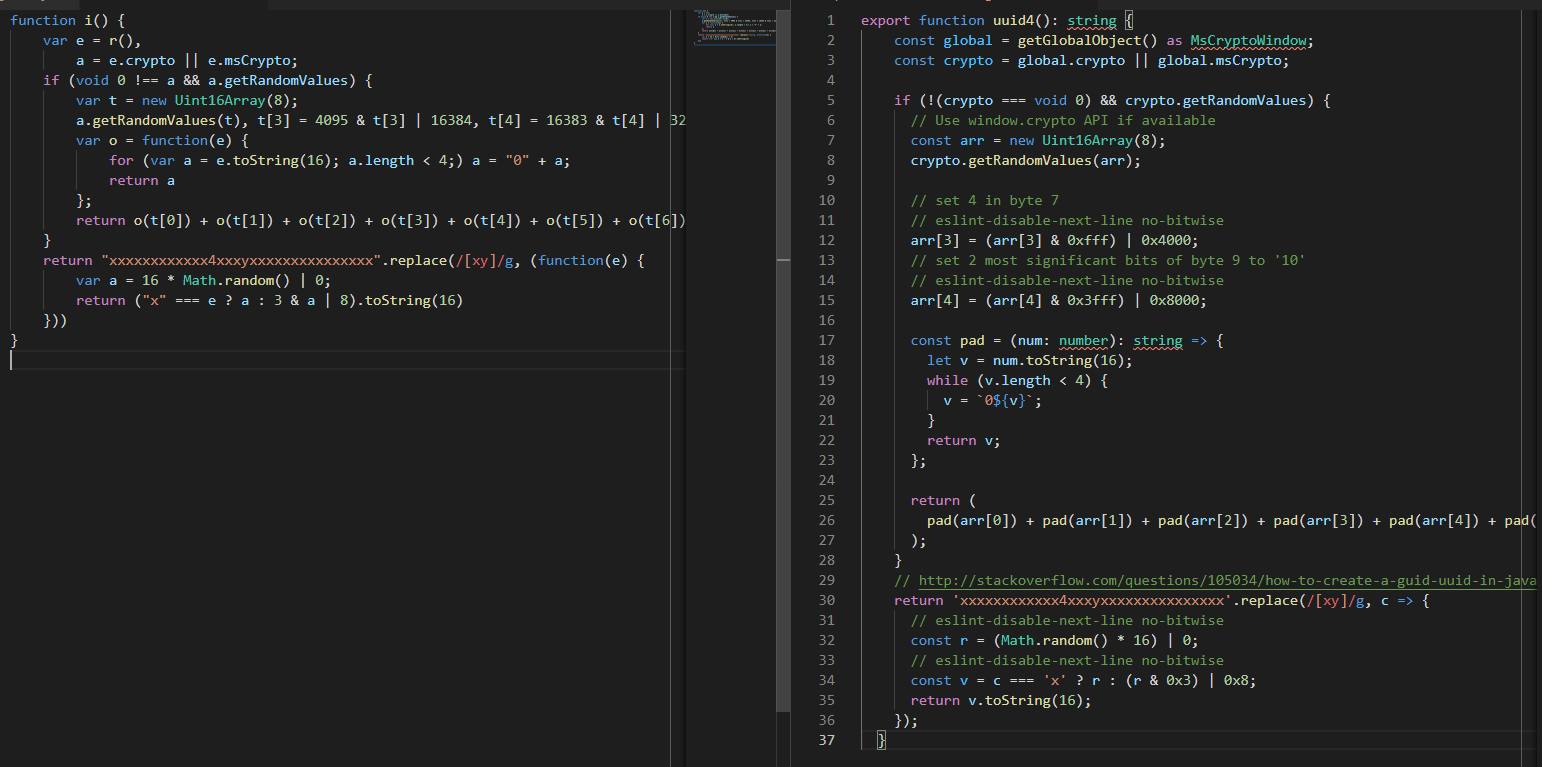

We find the string in misc.ts. It's a TypeScript file. Often, we find the exact module and it's a matter of looking at the actual module and effortlessly renaming.

Functions side by side (open the image in a new tab to see it in full-size)

Functions side by side (open the image in a new tab to see it in full-size)

Rename function i() to function uuid4():

- Click on

ior put you cursor besides it. - Press

F2. - Enter

uuid4and press Enter. - The function will be renamed.

- Save changes.

Renaming function i

Renaming function i

We can do more, var e = r(), is const global = getGlobalObject(). But, this

is not as important as renaming functions.

Unfortunately, we did not find the exact source we saw how to do this. As an

exercise, try reversing the s(e) function (after uuid4). The final result is

easier to read:

2844 reversed

2844 reversed

The Pairing Code

It's very tempting to go through all the modules and rename as much as we can but we can spend our time better.

Note: There are multiple ways to get to the application's logic code. Some examples:

- Search for the

EXTENSION/LOGINstring (we saw it in the handshake). Strings are usually not obfuscated. - Search for the WebSocket (ws) module strings and fields.

- E.g.,

ws://.

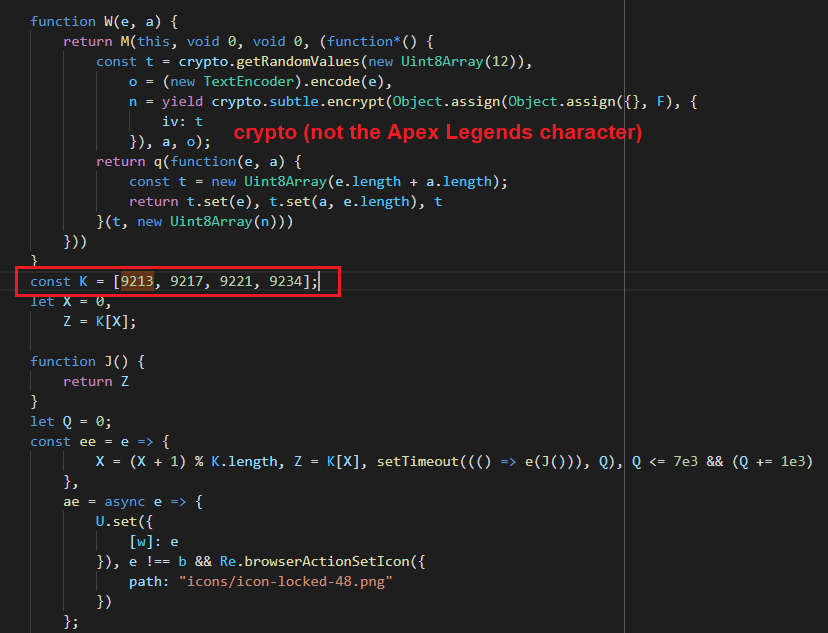

- E.g.,

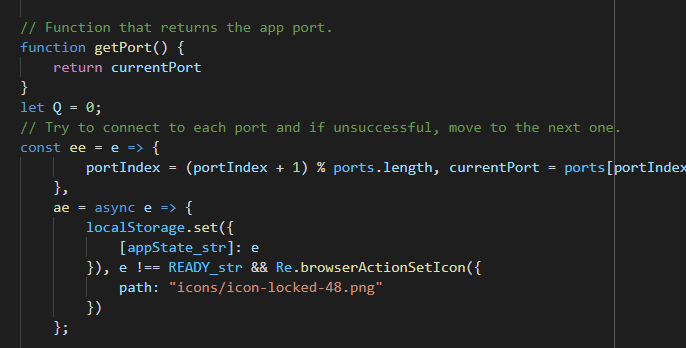

I knew the WebSocket used port 9213 so I searched for that. I landed in a very

interesting part of code with a bunch of crypto(graphy) function calls.

9213 in code

9213 in code

The K array contains the server's ports. It goes through them one by one and

tries to connect. The desktop app probably does the same when setting up the

server.

We do not need to know how each function exactly works. For example, the ee

function tries one port, waits for a bit and tries another.

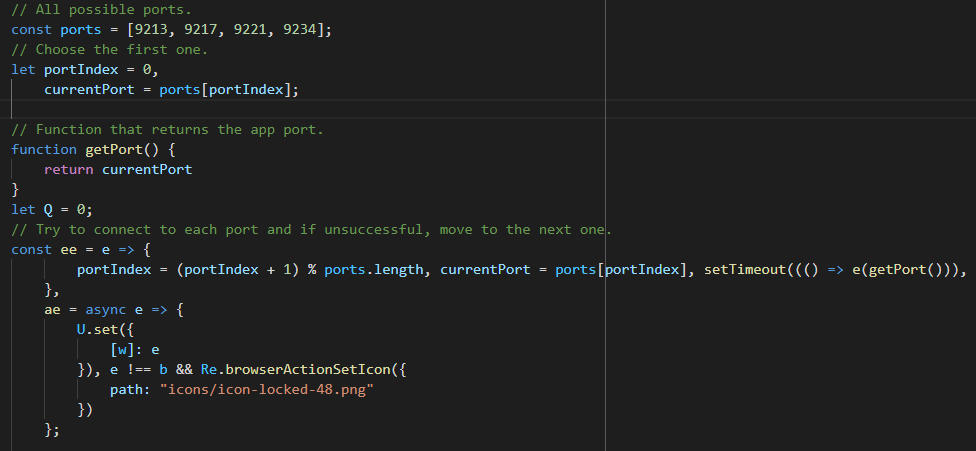

Port section renamed

Port section renamed

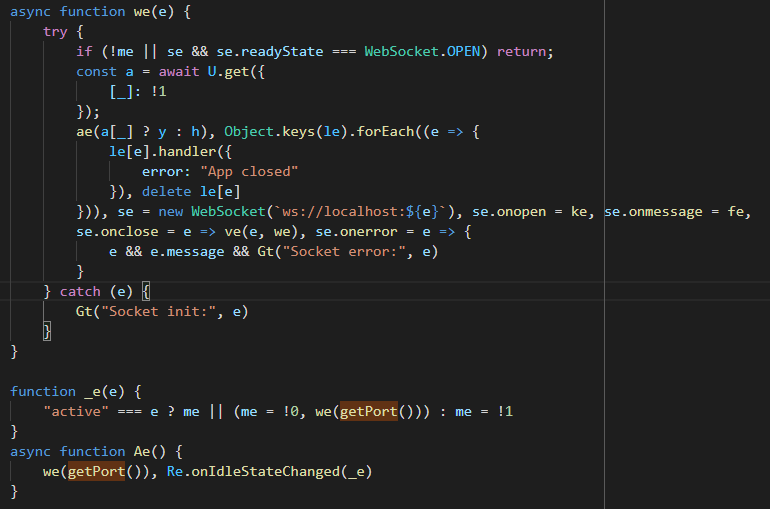

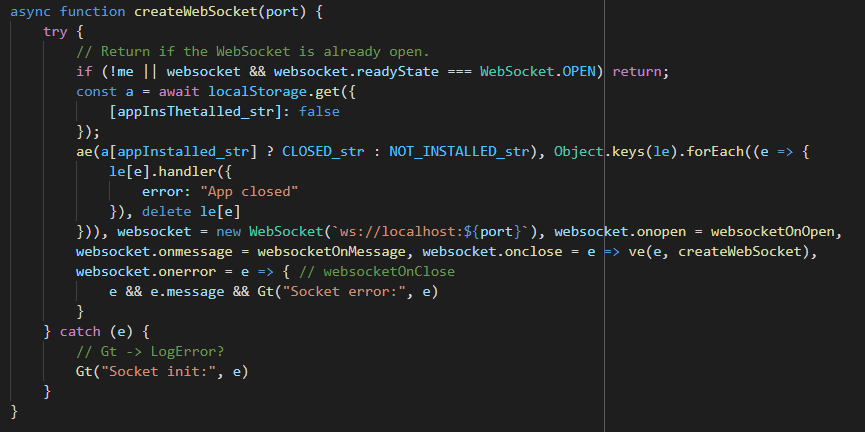

Searching for getPort gets to the WebSocket section. See we(e).

The WebSocket function

The WebSocket function

se is the WebSocket object. The event handlers for onmessage (it's fe) and

others are assigned here. We can rename them now.

The U function is an interesting case:

const a = await U.get({

[appInstalled_str]: !1 // ["appInstalled"]: false

});

ctrl+click on it to go to its definition.

G = t(3150);

const U = {

get: async function(e) {

return G.storage.local.get(e)

},

set: async function(e) {

return G.storage.local.set(e)

},

remove: function(e) {

return G.storage.local.remove(e)

}

};

It deals with local storage. We can just call it LocalStorage. The API is at

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Mozilla/Add-ons/WebExtensions/API/storage/local.

Think of it as an extension specific key-value store.

G is either the browser object or chrome (we are in a Chrome web store

extension after all). But does it matter? We know enough to rename U to

LocalStorage.

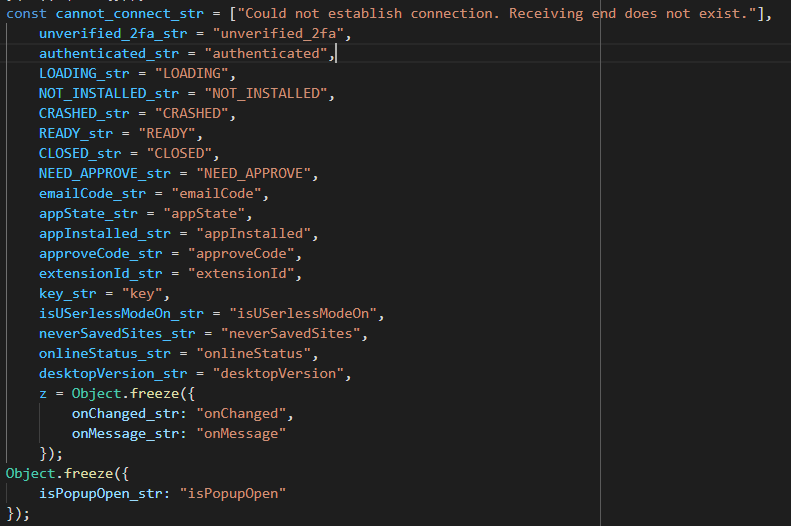

If you click on _ in the original code (now it's appInstalled_str) we get to

a bunch of constants that we can rename. I like to add _str to the end of

their variables to remember they are constants. You can also replace the

variable with the actual string manually (["appInstalled"]: false):

Some renamed constants

Some renamed constants

The function's final form:

createWebSocket

createWebSocket

Logically, our next targets are the WebSocket event handlers. They have custom

application code. The handshake starts in websocketOnOpen. ctrl+click to get

here:

websocketOnOpen before renames

websocketOnOpen before renames

ctrl+click on the ae(LOADING_str) function (called as ae("LOADING")).

Turns out we have seen it before. It's near the getPort function.

ae function

ae function

ae = async applicationState => {

localStorage.set({

// Set application state to local storage

[appState_str]: applicationState // ["appState"]: applicationState

}), applicationState !== "READY" && Re.browserActionSetIcon({

path: "icons/icon-locked-48.png"

})

};

See how renaming helps as we dive deeper into the application code?

aesets the valueappStatekey in the extension's local storage to the function's parameter (LOADINGhere).- If the function parameter is not

READYit callsRe.browserActionSetIconwith an object with a field namedpath.pathpoints to an icon in the extension.

I renamed ae to setAppState. We can easily guess Re.browserActionSetIcon

is setting the extension's icon to icons/icon-locked-48.png.

![]() Extension's `locked` icon

Extension's `locked` icon

Next, websocketOnOpen is trying to retrieve the value of key from local

storage.

async function websocketOnOpen() {

try {

setAppState(LOADING_str);

const e = (await localStorage.get({ // get the value of "key" from local storage

[key_str]: null // ["key"]: null

}))[key_str]; // ["key"]

if (e) {

ue = await

function(e) {

A few more symbol renames:

async function websocketOnOpen() {

try {

setAppState("LOADING"); // set application state to "LOADING"

const key = (await localStorage.get({ // get the value of "key" in local storage

["key"]: null // ["key"]: null

}))["key"]; // ["key"]

if (key) { // if "key exists" do these

ue = await

function(e) {

If the key exists we step into the if(key) block. It starts with this

in-line function call.

async function websocketOnOpen() {

try {

setAppState("LOADING"); // set application state to "LOADING"

const key = (await localStorage.get({ // get the value of "key" in local storage

["key"]: null

}))["key"];

if (key) { // if "key exists" do these

a = await

function(e) { // What is this?

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return $(V(e))

}))

}(key);

What is function(e)? It's creating a generator function.

I have no clue what it is but when I see it I only care about what M returns

and not the wrapper. It is retuning $(V(e)) here. What does V(e) do?

function V(e) {

const a = new Uint8Array(e.length / 2);

for (let t = 0; t < e.length; t += 2) a[t / 2] = parseInt(e.substring(t, t + 2), 16);

return a

}

This is the equivalent of Python's unhexlify. It converts a hex string into

bytes. I did not even try and figure out the math. I saw it's creating a byte

array with half the length of input and then it iterates through it

two-char-at-a-time and calls parseInt(n, 16).

This kind of guessing is (in my opinion) the best skill you can hone as a reverse engineer and it comes with practice.

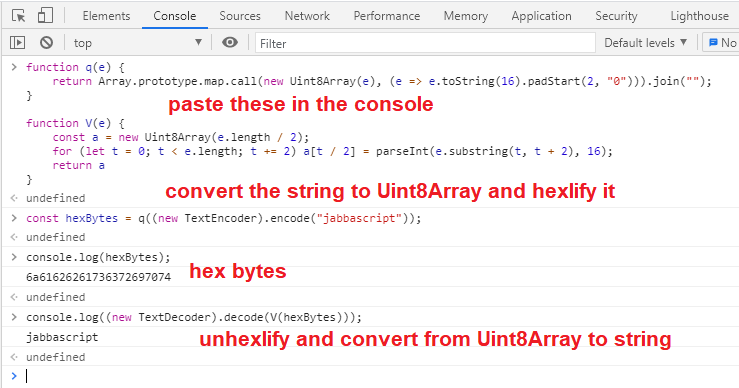

Quick Intro to JavaScript Dynamic Analysis with Browser DevTools

We already know how to debug JavaScript that is running in an extension or a web page. But what about small snippets of code like an individual function? We can analyze them in two places in the browser:

- Console

- Snippets

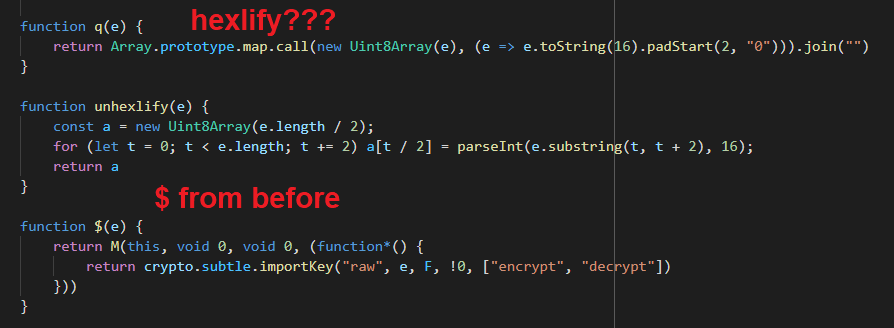

Look at the function above unhexlify. Can you guess what it does without

thinking? It's hexlify, it comes before unhexlify (lol).

hexlify in code

hexlify in code

Copy/paste the function into a REPL and the pass some input, analyze the output, and/or debug the execution. You can either use an online JavaScript REPL or paste it in the browser's console.

unhexlify and hexlify in action

unhexlify and hexlify in action

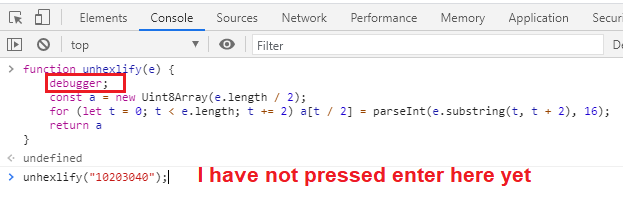

If you want to debug, you can add the statement debugger; in your code. I

pasted the unhexlify function in the console (see the extra debugger;

statement) and then called it with an input. In the following picture I have not

pressed enter on the last line yet.

unhexlify in the console

unhexlify in the console

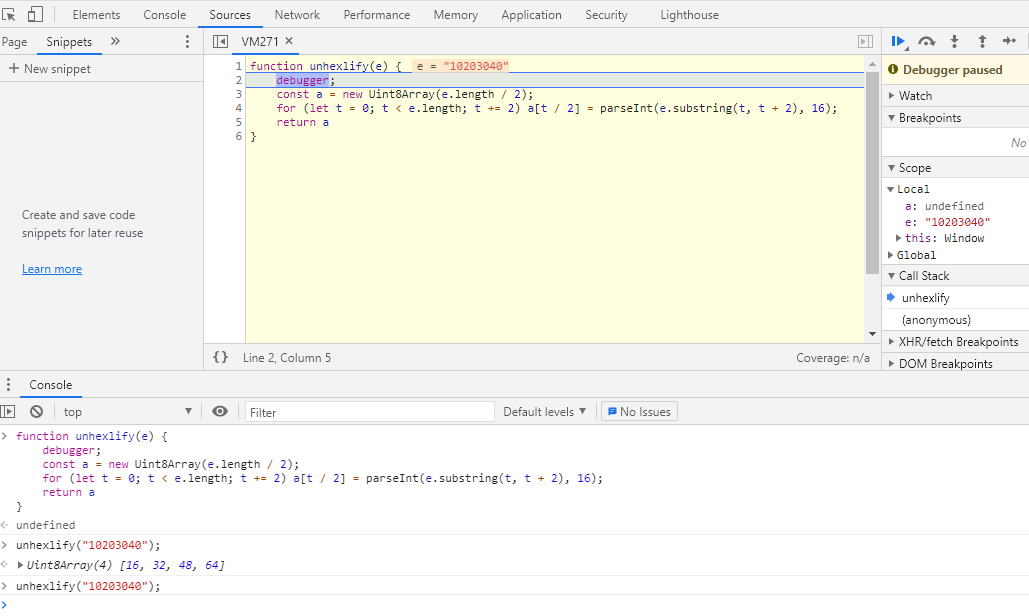

After pressing enter, unhexlify is called and we switch to the Sources tab.

Debugger triggered

Debugger triggered

Tip: It's easier for me if I convert lines that do several things into

multiple lines and add intermediate variables. Change the code as you see fit

(make sure the functionality is not altered) but do whatever you can to make it

easier. This is not supposed to be hard (and if anyone tells you so, kick them

in the butt). unhexlify above is now the following code (note the intermediate

variable).

function unhexlify(hexString) {

debugger;

const hexBytes = new Uint8Array(hexString.length / 2);

for (let i = 0; i < hexString.length; i += 2)

{

let twoChars = hexString.substring(i, i + 2); // added intermediate variable

hexBytes[i / 2] = parseInt(twoChars, 16);

}

return hexBytes

}

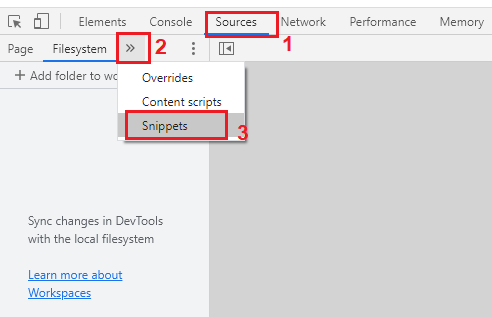

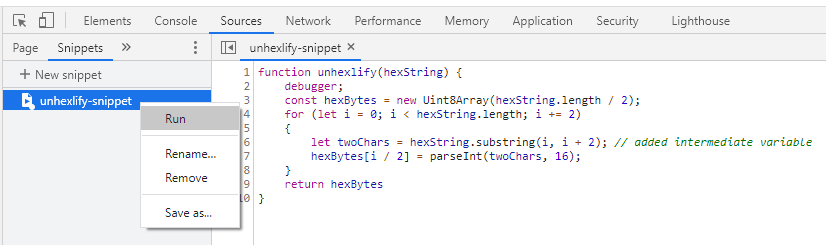

We can also use DevTools' snippets.

- Open a new browser window and press

F12to open the DevTools. - Switch to the

Sourcestab and thenSnippets.Snippetsmight be hidden so you might need to click on>>. Snippets in DevTools

Snippets in DevTools

- Click on

New snippetand give it a name. - Paste the function in it.

- Having the

debuggerhere is optional because we can set breakpoints before execution.

- Having the

- Press

ctrl+enteror right-click the snippet in the left sidebar and selectRun. - The snippet should run once but will do nothing because it just adds the

function to the scope. Now, we can call the function in the console.

Running the snippet

Running the snippet - Type

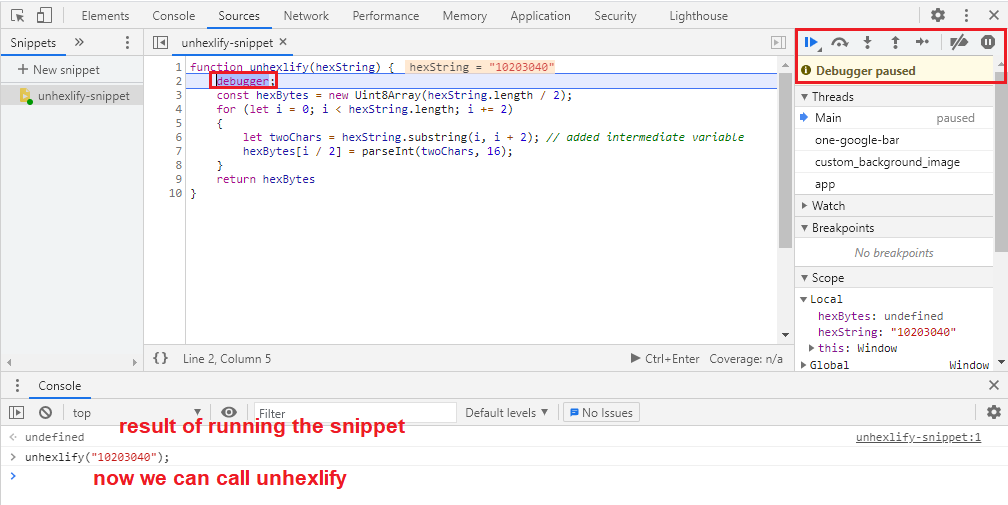

unhexlify("10203040");in the console. - The snippet should stop at

debuggeror any breakpoint. Debugging the snippet

Debugging the snippet

Enter Cryptography

Back to the task at hand. The $ function is also there. We are reaching the

crypto region.

function $(e) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", e, F, !0, ["encrypt", "decrypt"])

}))

}

SubtleCrypto are a set of browser cryptography APIs. The documentation warns:

If you're not sure you know what you are doing, you probably shouldn't be using this API.

Luckily for me, I am the CryptoGangsta so I can do what

I want. All importKey parameters except F are unknown. With a ctrl+click

we get to it:

const F = {

name: "AES-GCM",

length: 256

},

H = {

name: "ECDH",

namedCurve: "P-384"

};

Looking at the parameters for importKey we see the 3rd

parameter is named algorithm. MDN says:

For AES-CTR, AES-CBC, AES-GCM, or AES-KW: Pass the string identifying the algorithm or an object of the form { "name": ALGORITHM }, where ALGORITHM is the name of the algorithm.

So F is the algorithm object that tells the function we are importing an

AES-GCM key of length 256. Remember it was coming from the item named key

in local storage?

We can also figure out what H is, too. It's the ECDH algorithm object.

For ECDSA or ECDH: Pass an EcKeyImportParams object.

EcKeyImportParams should have two fields:

name: EitherECDSAorECDH.namedCurve:P-256,P-384, orP-521which are NIST approved curves (backdoors added and removed here :^)).

Let's rename:

const AESGCMAlgo = {

name: "AES-GCM",

length: 256

},

ECDHAlgo = {

name: "ECDH",

namedCurve: "P-384"

};

$ becomes:

function $(e) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", e, AESGCMAlgo, true, ["encrypt", "decrypt"])

}))

}

importKey is called like this:

const result = crypto.subtle.importKey(

format, // "raw"

keyData, // e or the function parameter

algorithm, // { name: "AES-GCM", length: 256 }

extractable, // true

keyUsages // ["encrypt", "decrypt"]

);

It imports a array with the AES key bytes and returns (a promise with) a

CryptoKey which can be used to encrypt and decrypt stuff

(keyUsages).

function importAESKey(keyBytes) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", keyBytes, AESGCMAlgo, true, ["encrypt", "decrypt"])

}))

}

The Importance of Knowing Cryptography

Look at these two algorithms and take a couple of minutes to guess the

handshake's cryptographic algorithm. We have a symmetric encryption algorithm

(AES-GCM) and a key agreement algorithm (ECDH). How are these usually used

in conjunction? What other very popular cryptographic thingamajig does this

(hint: SSL/TLS)?

Each side sent an EXTENSION/LOGIN message which was a JSON object. It had a

key named key which was a long hex string. Knowing this, we can just skip a

few steps and look for crypto.subtle in the code to figure out what the

handshake does.

Reversing The Handshake

Immediately after the import function we have:

function Y(e) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return hexlify(yield crypto.subtle.exportKey("raw", e))

}))

}

What do you think it does? What comes with import? It exports a key as raw hex

bytes using exportKey. Name it exportKey.

function exportKey(key) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return hexlify(yield crypto.subtle.exportKey("raw", key))

}))

}

And we get to the main function.

function B(e, a) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

const t = yield function(e) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", unhexlify(e), ECDHAlgo, true, [])

}))

}(e), o = yield crypto.subtle.deriveBits(Object.assign(Object.assign({}, ECDHAlgo), {

public: t

}), a, 384);

return function(e) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return importAESKey(new Uint8Array(e))

}))

}(yield crypto.subtle.digest("SHA-256", o))

}))

}

Start by adding comments and rename some of the variables/parameters. There's no need to figure out what this blob does in one look.

function B(appECDHKeyHexBytes, a) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

const ecdhCryptoKey = yield function(ecdhKey) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", unhexlify(ecdhKey), ECDHAlgo, true, []) // import ECDH P-384 key

}))

}(appECDHKeyHexBytes), o = yield crypto.subtle.deriveBits(Object.assign(Object.assign({}, ECDHAlgo), {

public: ecdhCryptoKey

}), a, 384);

return function(aesKey) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return importAESKey(new Uint8Array(aesKey)) // import AES-GCM 256 key

}))

}(yield crypto.subtle.digest("SHA-256", o)) // SHA-256(o)

}))

}

First parameter is an ECDH key in hex bytes. We know this because we can see

it's unhexlified first and then passed to importKey with ECDHAlgo. This

returns an ECDH CryptoKey (ecdhCryptoKey). This ecdhCryptoKey is used in

crypto.subtle.deriveBits.

Those Object.assign calls are just style points. They create the first

parameter for deriveBits. The documentation says the first parameter is

algorithm.

algorithm is an object defining the derivation algorithm to use.

To use ECDH, pass an EcdhKeyDeriveParams object.

EcdhKeyDeriveParams looks like:

{

name: "ECDH",

public: // CryptoKey representing the public key of the other entity.

}

These assigns get the old ECDHAlgo object:

{

name: "ECDH",

namedCurve: "P-384"

}

and add a new field named public with value of ecdhCryptoKey:

{

name: "ECDH",

namedCurve: "P-384", // This will be ignored

public: ecdhCryptoKey

}

So we are calling deriveBits like this:

crypto.subtle.deriveBits(

{ name: "ECDH", public: ecdhCryptoKey }, // algorithm

a, // baseKey

384 // number of bits to derive

}

deriveBits with an ECDH algorithm object performs the ECDH key agreement.

- Each side generates a pair of ECDH keys. These should be on the same curve.

- Each side sends their public key to the other side.

- Each side calculates a shared secret using their own private key and the other side's public key.

Through Elliptic Curve cryptomagic these two shared secrets are the same. Now,

we know a or the second parameter for this function and deriveBits is the

extension's ECDH private key as a CryptoKey.

function generateEncryptionKey(appECDHKeyHexBytes, extensionECDHCryptoKey) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

const ecdhCryptoKey = yield function(ecdhKey) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", unhexlify(ecdhKey), ECDHAlgo, false, []) // import ECDH P-384 key

}))

}(appECDHKeyHexBytes), sharedSecret = yield crypto.subtle.deriveBits(Object.assign(Object.assign({}, ECDHAlgo), {

public: ecdhCryptoKey

}), extensionECDHCryptoKey, 384);

return function(aesKey) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

return importAESKey(new Uint8Array(aesKey)) // import AES-GCM 256 key

}))

}(yield crypto.subtle.digest("SHA-256", sharedSecret)) // SHA-256(sharedSecret)

}))

}

The last piece of the puzzle is the hash. The 384-bit shared secret is passed to

SHA-256 and returned. You are probably wondering why the hash? If we want 256

bits why not just pass 256 instead of 384 to deriveBits and use those?

There is another SubtleCrypto function named deriveKey which

does this and return a ready-to-use CryptoKey.

I looked at how these two were implemented in various browser libraries and it

seems like deriveKey is a deriveBits and an importKey. The code could have

been this:

subtle.crypto.deriveKey(

{ name: "ECDH", public: ecdhCryptoKey },

extensionECDHCryptoKey,

AESGCMAlgo, // { name: "AES-GCM", length: 256 }

true,

["encrypt", "decrypt"]

);

At this point we have already guessed what happens. But, let's trace it in the

code anyways. Searching for generateEncryptionKey we get to this function

(already renamed). It does the handshake and returns the message encryption AES

key:

async function doHandshake() {

// generate an ECDH keypair

const extensionKeyPair = await crypto.subtle.generateKey(ECDHAlgo, true, ["deriveBits"]),

extensionPubKey = await exportKey(extensionKeyPair.publicKey), // export the extension's public key

generatedExtensionId = await getOrGenerateExtensionId(), // generates and return a 9 digit base36 string

// outgoing extension message example:

// {

// "id": 1,

// "type": "EXTENSION/LOGIN",

// "key": "long-hex-value", // extension's public key

// "isFullScreen": false,

// "extensionId": "fdrk45blr",

// "browser": "edge"

// }

// send EXTENSION/LOGIN message and return the response from server

serverExtensionLoginMessage = await sendMessage({

type: "EXTENSION/LOGIN",

key: extensionPubKey,

isFullScreen: isExtensionFullScreen(),

extensionId: generatedExtensionId

}),

// incoming server message example:

// {

// "id": 1,

// "type": "EXTENSION/LOGIN",

// "key": "long-hex-value", // server's public key

// "isDesktopLaunchedOnSameUser": true

// }

// generate an AES-GCM 256 CryptoKey

messageEncryptionKey = await generateEncryptionKey(serverExtensionLoginMessage.key, extensionKeyPair.privateKey),

// export the AES key as bytes

messageEncryptionKeyBytes = await crypto.subtle.exportKey("raw", messageEncryptionKey),

// generate the 4-digit pairing code (called approve code in source) from the key

approveCode = new Uint8Array(messageEncryptionKeyBytes, 0, 2).join("").padStart(4, "0").substr(0, 4);

return await localStorage.set({

["appInstalled"]: true,

["approveCode"]: approveCode // store the approve code in local storage

}), messageEncryptionKey // return the AES encryption key

}

We see how the four-digit extension pairing code is generated.

function approveCode(messageEncryptionKeyBytes) {

return new Uint8Array(messageEncryptionKeyBytes, 0, 2).join("").padStart(4, "0").substr(0, 4);

}

It converts the key to Uint8 and returns the first four digits. Let's see what it means:

// Paste these two functions in the browser console

function unhexlify(e) {

const a = new Uint8Array(e.length / 2);

for (let t = 0; t < e.length; t += 2) a[t / 2] = parseInt(e.substring(t, t + 2), 16);

return a

}

function approveCode(messageEncryptionKeyBytes) {

return new Uint8Array(messageEncryptionKeyBytes, 0, 2).join("").padStart(4, "0").substr(0, 4);

}

// now we can call the function and see the result

hexBytes1 = unhexlify("1020304050");

Uint8Array(5) [16, 32, 48, 64, 80] // result

approveCode(hexBytes1); // command

"1632" // result

hexBytes2 = unhexlify("AABBCCDD"); // command

Uint8Array(4) [170, 187, 204, 221] // result

approveCode(hexBytes2); // command

"1701" // result

hexBytes3 = unhexlify("01020304"); // command

Uint8Array(4) [1, 2, 3, 4] // result

approveCode(hexBytes3); // command

"1234" // result

Bug: In the current version (2.33.14) if an approve code starts with 0

the desktop app will not accept it. If this happens refresh the extension page

to get a new one.

We also see how the extension ID (this is different from the extension ID in the Chrome web store) is generated. If it exists, it's retrieved from local storage, otherwise, a 9 digit base36 string is created:

async function getOrGenerateExtensionId() {

const storedExtensionId = (await localStorage.get({

["extensionId"]: ""

}))["extensionId"];

if (storedExtensionId) return storedExtensionId;

const generatedExtensionId = Math.random().toString(36).substr(2, 9);

return await localStorage.set({

["extensionId"]: generatedExtensionId

}), generatedExtensionId

}

The Handshake Demystified

We have cracked the handshake.

- Extension and the app generate a pair of ECDH P-384 keys.

- Send their public keys in an

EXTENSION/LOGINmessage. - Generate a 384-bit shared secret using ECDH.

- Use SHA-256 of this secret to encrypt messages using AES-GCM 256.

- The extension uses this key to generate the four-digit "approve code" and displays it.

- The user must enter this code in the desktop app.

- If the code is accepted, the extension and server use the encryption key to encrypt their messages and communicate.

Message Encryption and Decryption

At this point, we know the algorithm and the key but AES-GCM also needs an IV

for encryption/decryption and a tag for decryption. A good place to look for

these is the websocketOnMessage function.

Let's remember what an incoming message looks like:

{

"id": 2,

"data": "7919c0de7a34f60936145940dea3b758623d2cfc13b195739b1171adaa13db9d807dcb361..."

}Fortunately, the event handler is short.

async function websocketOnMessage(e) {

try {

const t = JSON.parse(e.data);

if (0 === t.id) await he(t);

else {

const e = await ge(t);

e.type === a.EXTENSION_LOGIN && (await localStorage.set({

[isUSerlessModeOn_str]: e.isUserless

}), await localStorage.set({

[T]: e.desktopVersion

})), le[t.id].handler(e), delete le[t.id]

}

} catch (e) {

Gt("socketMessenger:handleMessage:", e)

}

}

In an websocket onMessage event handler, the actual message is in e.data.

async function websocketOnMessage(event) {

try {

// incoming message is in event.data

// parse the incoming message

const parsedMessage = JSON.parse(event.data);

// if messageID === 0 pass it to another function

if (0 === parsedMessage.id) await handleZeroIDMessage(parsedMessage);

else {

// if id != 0, decrypt the message

const decryptedMessage = await decryptMessage(parsedMessage);

// if message type is "EXTENSION/LOGIN"

decryptedMessage.type === a.EXTENSION_LOGIN && (await localStorage.set({

["isUSerlessModeOn"]: decryptedMessage.isUserless

}),

await localStorage.set({

["desktopVersion"]: decryptedMessage.desktopVersion

})),

// add the message to the queue and call the message handler based

// on the encrypted message

messageQueue[parsedMessage.id].handler(decryptedMessage),

// delete it from the queue

delete messageQueue[parsedMessage.id]

}

} catch (e) {

Gt("socketMessenger:handleMessage:", e)

}

}

Decryption

If the message ID equals zero then a different function handles it. I have named

it handleZeroIDMessage. We don't need to look at it, what we need is the

function originally named ge (now decryptMessage) that does the decryption.

// const unencryptedMessageTypes = ["EXTENSION/LOGIN", "APP/CRASHED"];

const unencryptedMessageTypes = [a.EXTENSION_LOGIN, o.APP_CRASHED];

// ...

async function decryptMessage(message) {

// if type of message is one of the above, return the message. These messages are not encrypted

if (message.type && unencryptedMessageTypes.includes(message.type)) return message; // step 1

// if the message has a type but no data, return an empty object

// no data === nothing to decrypt

if (message.type && !message.data) return {}; // step 2

try {

// step 3: decrypt the message

const decryptedMessageText = await

function(ciphertext, key) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

const cipherTextBytes = unhexlify(ciphertext), // convert the ciphertext from hex string to bytes

iv = cipherTextBytes.slice(0, 12), // iv = first 12 bytes

cipher = cipherTextBytes.slice(12), // the rest is ciphertxt+tag

decryptedMessage = yield crypto.subtle.decrypt(Object.assign(Object.assign({}, AESGCMAlgo), {

iv: iv

}), key, cipher);

// return the decrypted message as text.

return (new TextDecoder).decode(new Uint8Array(decryptedMessage))

}))

}(message.data, messageEncryptionKey);

// parse the decrypted message as JSON and return the result

return JSON.parse(decryptedMessageText) // step 4

} catch (e) {

return {

error: "Invalid message"

}

}

}

- If the message has a type and it's one of the two unencrypted types, return the message. No need to decrypt.

- If the message has a type but no data, return an empty object.

- Decrypt message and return the result as text:

- IV: First 12 bytes.

- The rest is ciphertext + AES-GCM tag.

- Parse the decrypted message and JSON and return the result.

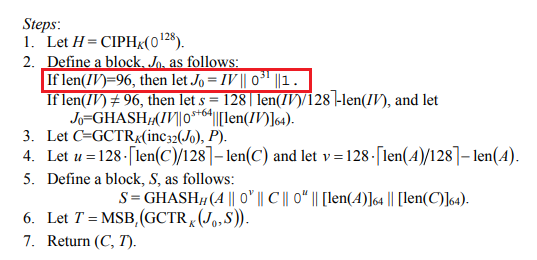

Side Quest: AES-GCM IV Size

AES-GCM's initialization vector is the first 12 bytes of the ciphertext. This is the recommended size (96 bits). Reading NIST publication 800-38D I saw references like this (bottom of page 8):

For IVs, it is recommended that implementations restrict support to the length of 96 bits, to promote interoperability, efficiency, and simplicity of design.

So a 96-bit IV is efficient, but why? Looking at the algorithms for encryption (page 15) and decryption (page 17) I can see that we need to calculate a GHASH when the IV is not 96 bits. Extra computation === bad!

AES-GCM encryption algorithm steps

AES-GCM encryption algorithm steps

Encryption

We don't need to find the encryption routine but it's good practice. Search for

crypto.subtle.encrypt in code.

function W(e, a) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

const t = crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(12)),

o = (new TextEncoder).encode(e),

n = yield crypto.subtle.encrypt(Object.assign(Object.assign({}, AESGCMAlgo), {

iv: t

}), a, o);

return hexlify(function(e, a) {

const t = new Uint8Array(e.length + a.length);

return t.set(e), t.set(a, e.length), t

}(t, new Uint8Array(n)))

}))

}

We have become pros at renaming variables.

function encryptMessage(message, key) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

// step 1: IV = generate 12 random bytes

const iv = crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(12)),

// step 2: convert the message to bytes

messageBytes = (new TextEncoder).encode(message),

// step 3: encrypt

ciphertext = yield crypto.subtle.encrypt(Object.assign(Object.assign({}, AESGCMAlgo), {

iv: iv

}), key, messageBytes);

// step 5 : return hexlify(iv + ciphertext)

return hexlify(function(e, a) { // step 4: concat(e, a)

const t = new Uint8Array(e.length + a.length);

return t.set(e), t.set(a, e.length), t

}(iv, new Uint8Array(ciphertext)))

}))

}

- Generate 12 bytes, this will be the initialization vector.

- Convert the message from text to bytes.

- ciphertext = AES-GCM(message, IV, key).

- Concatenate IV + ciphertext.

- Return hexlify(IV + ciphertext).

Add reverse engineering obfuscated JavaScript to your resume.

Image credit: an anime named Dagashi Kashi

Image credit: an anime named Dagashi Kashi

At this point we can create our own extension. But, why reinvent the wheel when we can modify the current extension to do what we want?

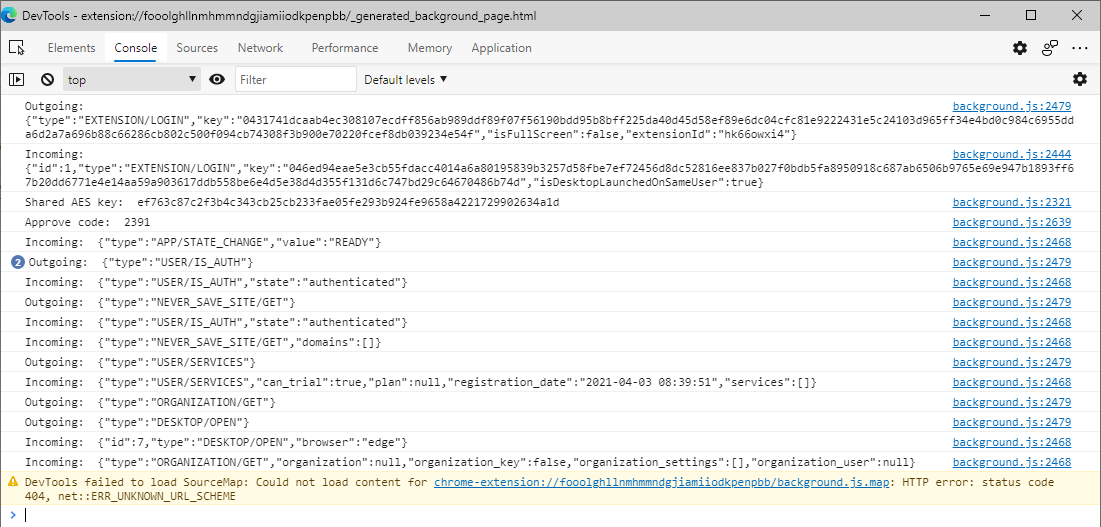

We can debug the extension and put watches on specific variables to see all incoming and outgoing messages but it's slow and painful. Instead, we can log a bunch of things to the console like:

- The shared key.

- The (four-digit) approve code.

- Incoming messages after decryption.

- Outgoing messages before encryption.

- Send arbitrary messages.

We will just add console.log messages to the extension's code at various places.

We know the shared key is either generated or read from local storage and then

passed to importAESKey. So, we modify that function like this:

function importAESKey(keyBytes) {

return M(this, void 0, void 0, (function*() {

console.log("Shared AES key: ", hexlify(keyBytes));

return crypto.subtle.importKey("raw", keyBytes, AESGCMAlgo, true, ["encrypt", "decrypt"]);

}))

}

The Approve Code

The code is generated inside the doHandshake function. Log it there.

async function doHandshake() {

// ...

approveCode = new Uint8Array(messageEncryptionKeyBytes, 0, 2).join("").padStart(4, "0").substr(0, 4);

console.log("Approve code: ", approveCode);

return await localStorage.set({

["appInstalled"]: true,

["approveCode"]: approveCode

}), messageEncryptionKey

}

Incoming Messages After Decryption

We need to log the messages in the decryptMessag function in two places. Not

every message is decrypted (e.g., EXTENSION/LOGIN).

- Create a block for the first

ifand print the message. This will print the unencrypted types. - Add a new line just before the second return of

decryptMessageto print decrypted messages.

The modified code is:

async function decryptMessage(message) {

if (message.type && unencryptedMessageTypes.includes(message.type))

{

// log unecrypted message.

console.log("Incoming:", JSON.stringify(message));

return message;

}

try {

// ...

const decryptedMessageText = await

function(ciphertext, key) {

// ...

}(message.data, messageEncryptionKey);

// log the decrypted message

console.log("Incoming:", decryptedMessageText);

// parse the decrypted message as JSON and return the result

return JSON.parse(decryptedMessageText)

} catch (e) {

// ...

}

}

Outgoing Messages Before Encryption

The best location is the sendMesage function.

function sendMessage(e) {

console.log("Outgoing:", JSON.stringify(e));

// ...

}

Console is lit!

Console logs

Console logs

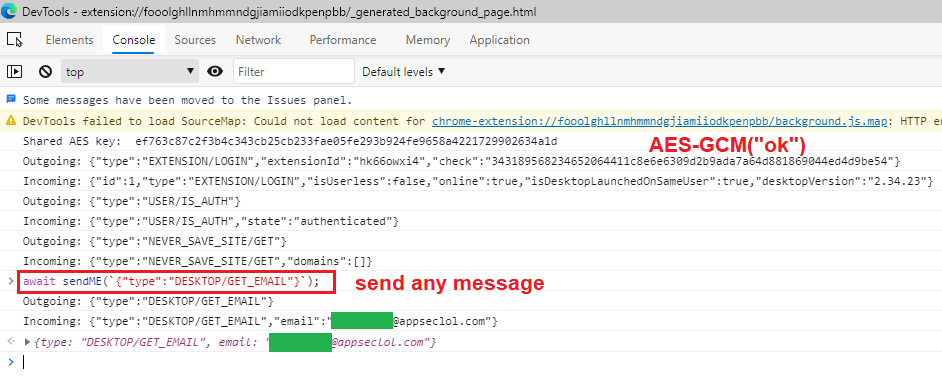

Send Arbitrary Messages

This was a fun one. I could see message but I also wanted to send my own

messages without creating a client. A slow way to do this is putting a

breakpoint in sendMessage just before the encryption routine. Then we can

modify outgoing messages.

A much better way is to send messages from the console by calling sendMessage

(which did not work).

sendMessage(JSON.parse(`{"type":"DESKTOP/OPEN"}`));

VM114:1 Uncaught ReferenceError: sendMessage is not defined

at <anonymous>:1:1

After an hour of troubleshooting I realized it's because I need to call it like

foo.bar.whatever.sendMessage. I realized I can create my own function in the

code and add it to the window object (e.g., make it global) and then call it

in the console and send arbitrary messages.

I added it to the extension code right after sendMessage.

// my own function

async function sendME(rawMessage) {

return sendMessage(JSON.parse(rawMessage));

}

// make it global

window.sendME = sendME;

Then I could do this in the console inside the extension's DevTools:

await sendME(`{"type":"USER/IS_AUTH"}`);

Outgoing: {"type":"USER/IS_AUTH"}

Incoming: {"type":"USER/IS_AUTH","state":"authenticated"}

Send any message from the console

Send any message from the console

This is pretty fun. We can use this technique to call any extension function manually in the console. We can start hacking at the extension and the desktop app.

Well, a shit ton. See the What Are We Gonna Learn Here Today? section up top.

Some lessons learned while reversing JavaScript:

- Search for strings and field/property names to find open source modules.

- They are not usually obfuscated. Error message are good candidates.

- Search in the obfuscated code for field/property names of the kind of objects

you are looking for. E.g.,

onmessagebecause we are looking for a WebSocket object. - You don't need to rename everything. Give priority to function names

especially in open source sections. Use the extra time to figure out what the

custom application code is doing.

- In this example, we don't care how the

wsmodule works internally. We just rename and chase the event handlers because they contain app code.

- In this example, we don't care how the

- Save early and often. As I said, I use git and commit every few changes.

- With this kind of high-speed reversing, it's very easy to mess up.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh