Targeted attacks

Putting the ‘A’ into APT

In December, SolarWinds, a well-known IT managed services provider, fell victim to a sophisticated supply-chain attack. The company’s Orion IT, a solution for monitoring and managing customers’ IT infrastructure, was compromised by threat actors. This resulted in the deployment of a custom backdoor, named Sunburst, on the networks of more than 18,000 SolarWinds customers, including many large corporations and government bodies, in North America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

One thing that sets this campaign apart from others, is the peculiar victim profiling and validation scheme. Out of the 18,000 Orion IT customers affected by the malware, it seems that only a handful were of interest to the attackers. This was a sophisticated attack that employed several methods to try to remain undetected for as long as possible. For example, before making the first internet connection to its C2s, the Sunburst malware lies dormant for up to two weeks, preventing easy detection of this behaviour in sandboxes. In our initial report on Sunburst, we examined the method used by the malware to communicate with its C2 (command-and-control) server and the protocol used to upgrade victims for further exploitation.

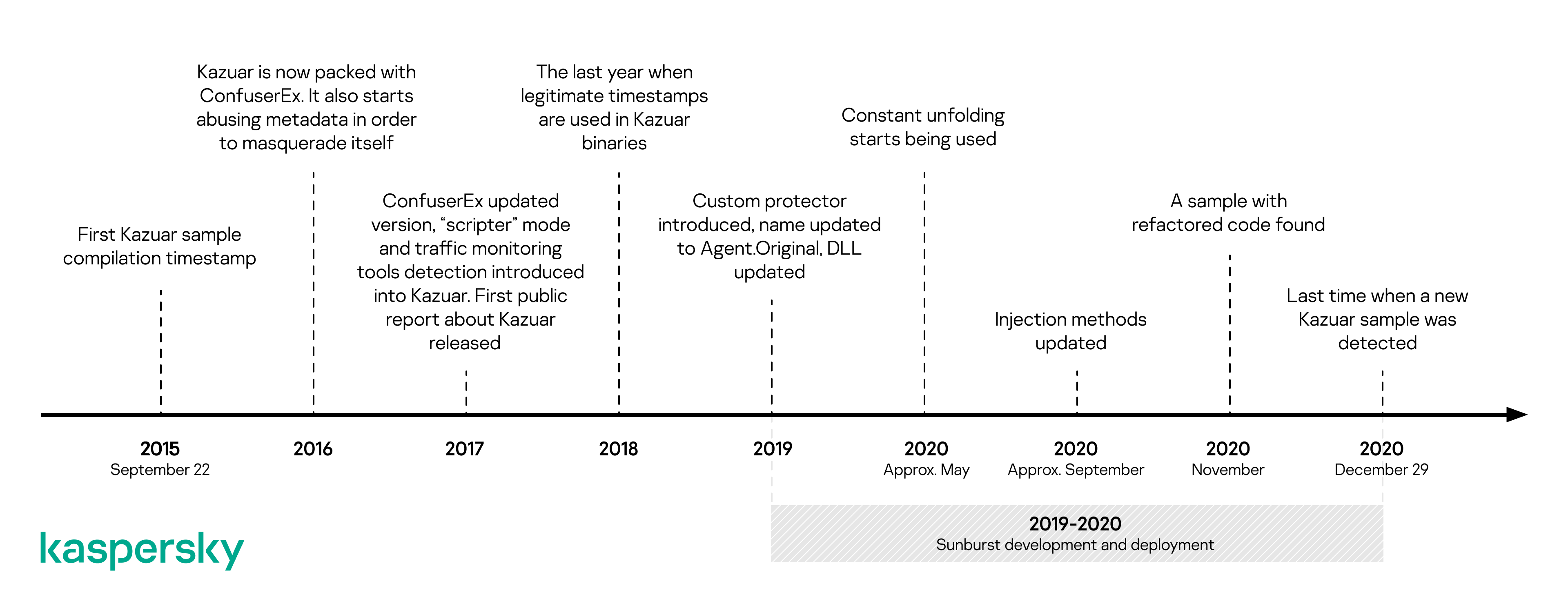

Further investigation of the Sunburst backdoor revealed several features that overlap with a previously identified backdoor known as Kazuar, a .NET backdoor first reported in 2017 and tentatively linked to the Turla APT group.

The shared features between Sunburst and Kazuar include the victim UID generation algorithm, code similarities in the initial sleep algorithm and the extensive usage of the FNV1a hash to obfuscate string comparisons. There are several possibilities: Sunburst may have been developed by the same group as Kazuar; the developers of Sunburst may have adopted some ideas or code from Kazuar; both groups obtained their malware from the same source; some Kazuar developers moved to another team, taking knowledge and tools with them; or the developers of Sunburst introduced these links as a form of false flag. Hopefully, further analysis will make things clearer.

Lazarus targets the defence industry

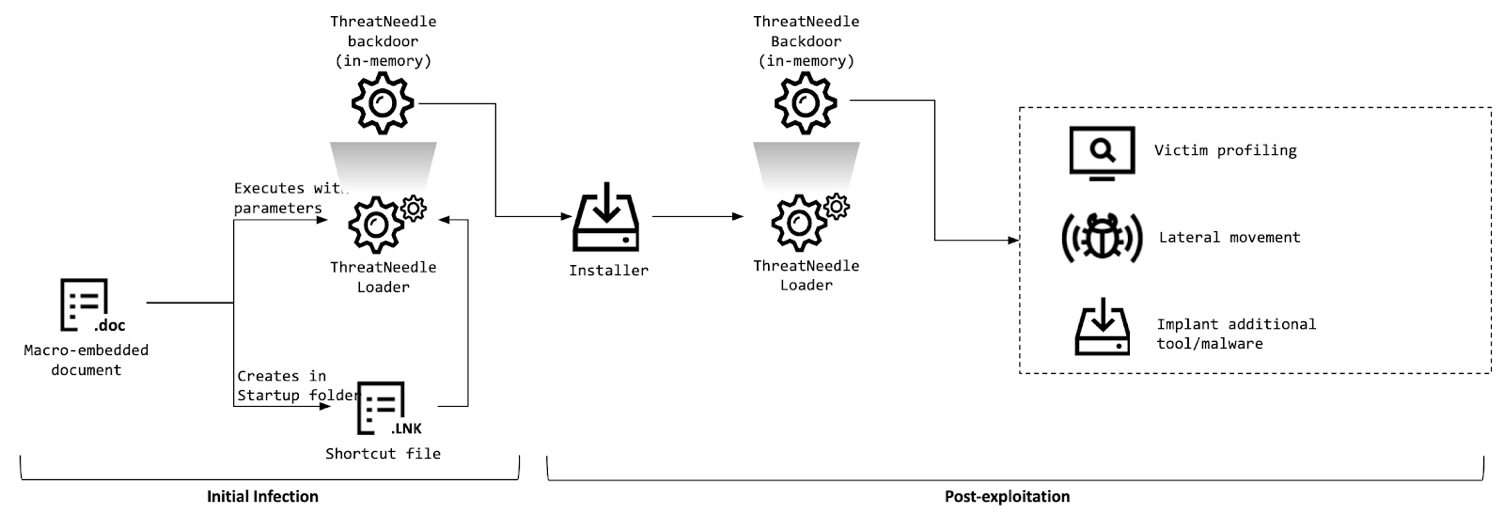

We have observed numerous activities of the Lazarus group over many years, with the threat actor changing targets depending on its objectives. Over the last two years, we have tracked Lazarus’s use of ThreatNeedle, an advanced malware cluster of Manuscrypt (aka NukeSped), to target several industries. While investigating attacks on the defense industry in mid-2020, we were able to observe the complete life-cycle of an attack, uncovering more technical details and links to the group’s other campaigns.

Lazarus made use of COVID-19 themes in its spear-phishing emails, embellishing them with personal information gathered using publicly available sources. Once the victim opens an infected document and agrees to enable macros, the malware is dropped onto the system and proceeds to a multi-stage deployment procedure.

After gaining an initial foothold, the attackers gathered credentials and moved laterally, seeking crucial assets in the victim’s environment. They overcame network segmentation by gaining access to an internal router machine and configuring it as a proxy server, allowing them to exfiltrate stolen data from the victim’s intranet to their remote server.

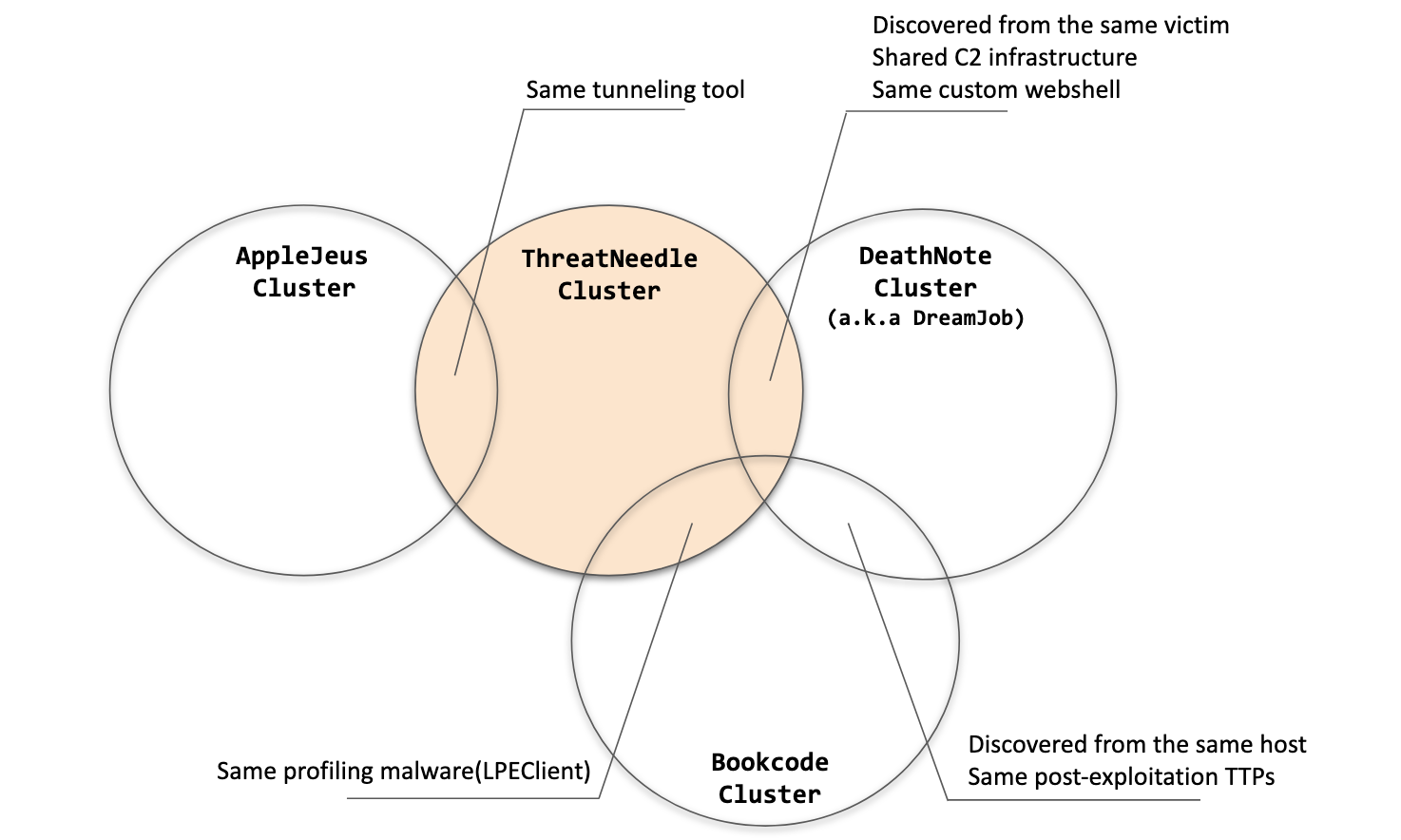

We have been tracking ThreatNeedle malware for more than two years and are highly confident that this malware cluster is attributed only to the Lazarus group. During this investigation, we were able to find connections to several other clusters belonging to the Lazarus group.

MS Exchange zero-day vulnerabilities exploited in the wild

On March 2, Microsoft released out-of-band patches for four zero-day vulnerabilities in Exchange Server that are being actively exploited in the wild (CVE-2021-26855, CVE-2021-26857, CVE-2021-26858 and CVE-2021-27065). The vulnerabilities allow an attacker to gain access to an Exchange server, create a web shell for remote server access and steal data from the victim’s network.

Microsoft attributed the attacks to a threat actor called Hafnium, although other researchers have reported that there are also other groups exploiting the vulnerabilities to launch attacks.

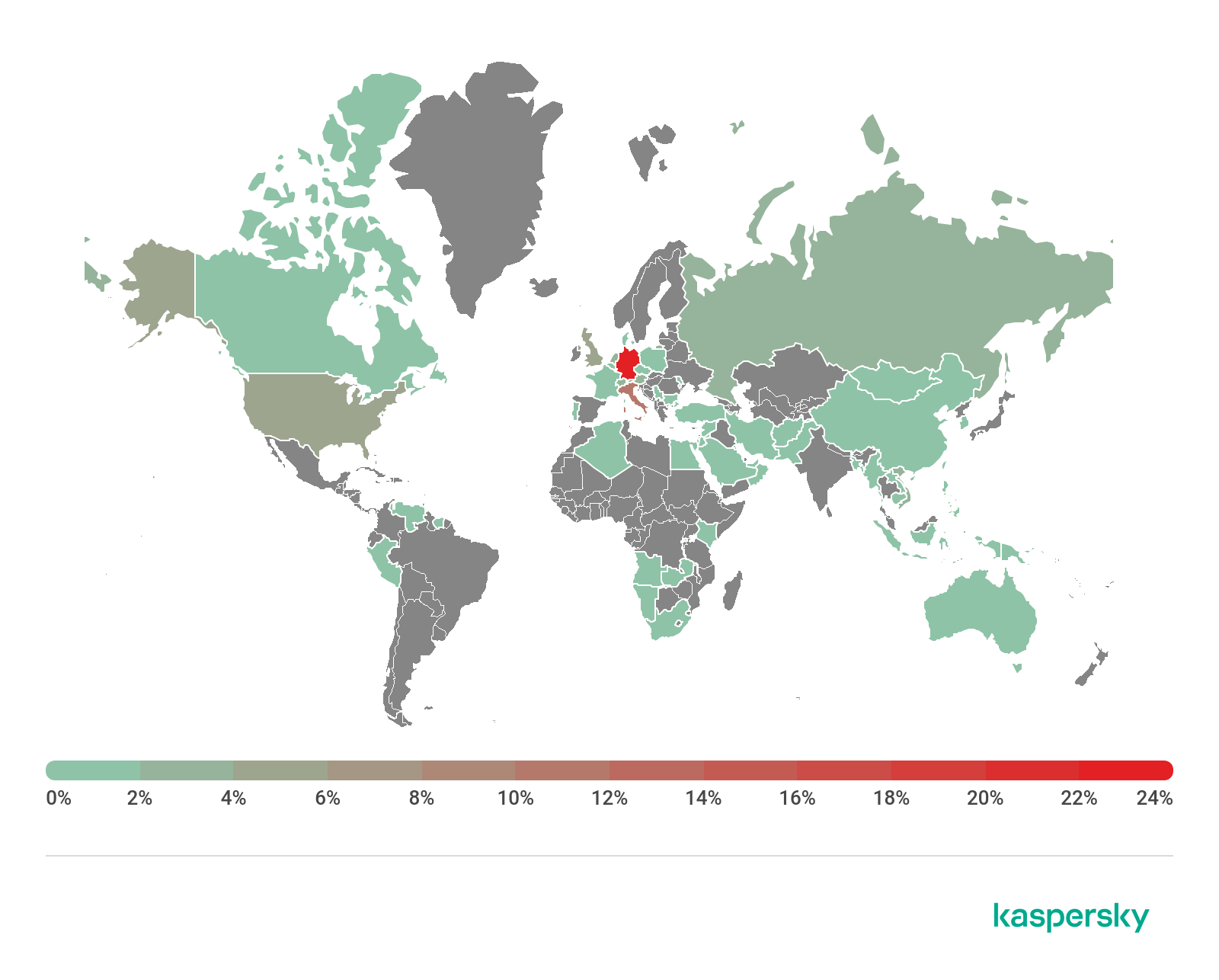

Our threat intelligence indicates that companies across the globe have been targeted in attacks that exploit these vulnerabilities – with the greatest focus on Europe and the US.

Kaspersky products protect against this threat with behavior-based detection and exploit prevention components. We also detect and block the backdoors used in the exploitation of these vulnerabilities. Our EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) solution helps to identify attacks in the early stages by marking suspicious actions with special IoA (Indicators of Attack) tags and by creating corresponding alerts.

Kaspersky products protect against this threat with behavior-based detection and exploit prevention components. We also detect and block the backdoors used in the exploitation of these vulnerabilities. Our EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) solution helps to identify attacks in the early stages by marking suspicious actions with special IoA (Indicators of Attack) tags and by creating corresponding alerts.

Our recommendations for staying safe from attacks using these vulnerabilities can be found here.

Ecipekac: sophisticated multi-layered loader discovered in A41APT campaign

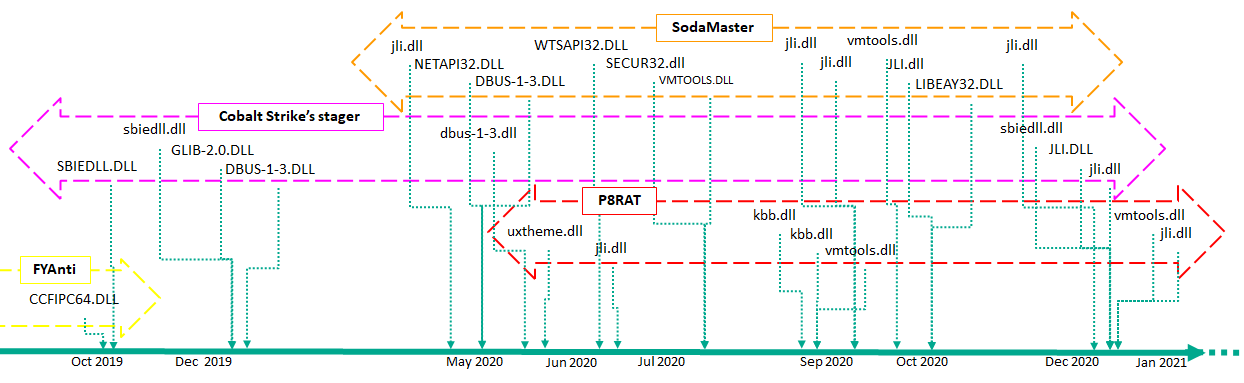

A41APT is a long-running campaign, active from March 2019 to the end of December 2020, that has targeted multiple industries, including Japanese manufacturing and its overseas bases. We believe, with high confidence, that the threat actor behind this campaign is APT10.

One particular piece of malware from this campaign is called Ecipekac (aka DESLoader, SigLoader, and HEAVYHAND). It is a very sophisticated multi-layer loader module used to deliver payloads such as SodaMaster, P8RAT, and FYAnti which in turn loads QuasarRAT.

The operations and implants of the campaign are remarkably stealthy, making it difficult to track the threat actor’s activities. The threat actor behind the campaign implements several measures to conceal itself and make it more difficult to analyze. Most of the malware families used in the campaign are fileless malware and have not been seen before.

The operations and implants of the campaign are remarkably stealthy, making it difficult to track the threat actor’s activities. The threat actor behind the campaign implements several measures to conceal itself and make it more difficult to analyze. Most of the malware families used in the campaign are fileless malware and have not been seen before.

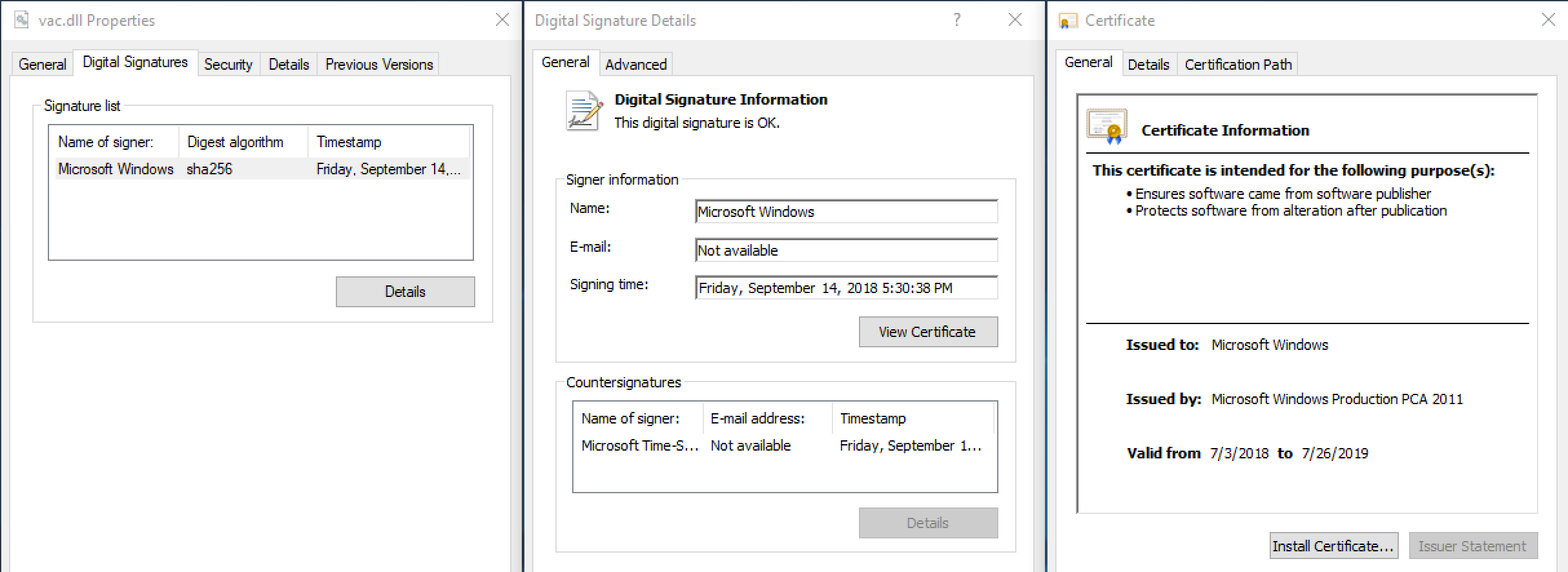

We believe that the most significant aspect of the Ecipekac malware is that the encrypted shellcodes are inserted into digitally signed DLLs without affecting the validity of the digital signature.

When this technique is used, some security solutions cannot detect these implants. Judging from the main features of the P8RAT and SodaMaster backdoors, we believe these modules are downloaders responsible for downloading further malware which we have so far been unable to obtain.

You can find out more about the campaign here.

Other malware

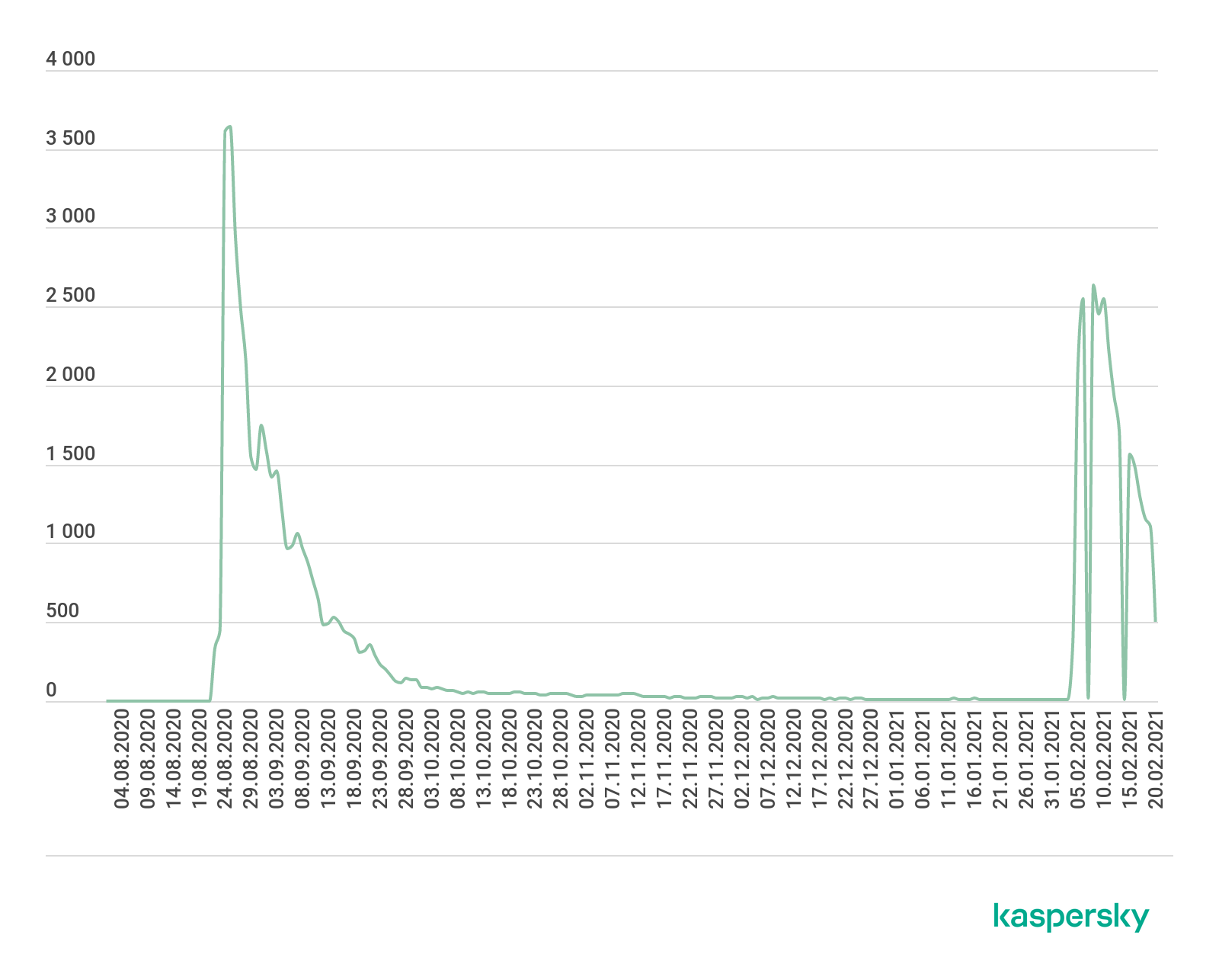

Some time ago, we discovered a number of fake applications being used to deliver a Monero crypto-currency miner to target computers. The fake programs are distributed through malicious websites that may be listed in the victim’s search results. We believe this is a continuation of a campaign last summer, reported by Avast, in which the malware masqueraded as the Malwarebytes antivirus installer. In the latest campaign, we observed the malware impersonating several applications: the ad blockers AdShield and Netshield, as well as the OpenDNS service.

Once the victim has started the program, it changes the DNS settings on the device so that all domains are resolved through the attackers’ servers: this prevents the victim from accessing certain antivirus sites. The malware then updates itself: the update also downloads and runs a modified Transmission torrent client, which sends the ID of the targeted computer, along with installation details, to the C2 server. It then downloads and installs the miner.

Data from Kaspersky Security Network showed that, from February 2021 until the time we published our report, there were attempts to install fake applications on the devices of more than 7,000 people. At the peak of the current campaign, more than 2,500 people were attacked each day, with most victims located in Russia and CIS countries.

Ransomware encrypting virtual hard disks

Ransomware gangs are exploiting vulnerabilities in VMware ESXi to target virtual hard disks and encrypt the data stored on them. The ESXi hypervisor lets multiple virtual machines store information on a single server using the SLP (Service Layer Protocol).

The first vulnerability (CVE-2019-5544) can be used to carry out heap overflow attacks. The second (CVE-2020-3992) is a Use-After-Free (UAF) vulnerability related to the incorrect use of dynamic memory during program operation. Once attackers have been able to gain an initial foothold in the target network, they can use the vulnerabilities to generate malicious SLP requests and compromise data storage.

The vulnerabilities are being exploited by RansomExx. The Darkside group is reportedly using the same approach; and the attackers behind the BabuLocker Trojan have also hinted that they are able to encrypt ESXi.

macOS developments

Towards the end of last year, Apple unveiled machines powered by its own M1 chip, designed to replace Intel’s processors in its computers. The Apple M1, a direct relative of the processors used in the iPhone and iPad, will ultimately allow Apple to unify its software under a single architecture.

Just a few months after the release of the first Apple M1 computers, malware writers had already recompiled their code to adapt it to the new architecture.

These include the developers of XCSSET, malware first discovered last year, which targets Mac developers by injecting a malicious payload into Xcode IDE projects on the victim’s Mac. This payload is subsequently executed during the building of project files in Xcode. XCSSET modules are able to read and dump Safari cookies, inject malicious JavaScript code into various websites, steal files and information from applications such as Notes, WeChat, Skype, Telegram and others, and encrypt files. The samples we have observed include some compiled specifically for the Apple Silicon chips.

Silver Sparrow is another new threat that targets the M1 chip. This malware introduces a new way for malware writers to abuse the default packaging functionality: instead of placing a malicious payload inside pre-install or post-install scripts, they hid one in the Distribution XML file. This payload uses JavaScript API to run bash commands in order to download a JSON configuration file. The sample extracts a URL from the “downloadURL” field for the next download. An appropriate Launch Agent is also created for persistent execution of the malicious sample. The JavaScript payload can be executed regardless of chip architecture, but analysis of the package file makes it clear that it supports both Intel and M1 chips.

Most malicious objects detected for the macOS platform are adware. The developers of these programs are also updating their code to include support for the M1 chip, including the Pirrit and Bnodlero families.

You can find technical details, along with our FAQ on M1 threats, here.

Cybercriminals don’t just add support for new platforms: sometimes they use new programming languages to develop their ‘products’. Recently, macOS adware developers have been paying more attention to new languages, apparently in the hope that such code will be more opaque to virus analysts who have little or no experience with the newer languages. We have already seen quite a few samples written in Go, and recently cybercriminals have turned their attention to Rust as well. You can read our analysis of a new adware program called Convuster here.

Secondhand news

There’s a strong market in secondhand computing devices. Some of our researchers recently looked at the security implications of buying and selling secondhand devices: their aim was to see what traces are left behind on laptops and other storage data when people sell them.

The overwhelming majority of the devices we investigated contained at least some traces of data – mostly personal but some corporate. Researchers were able to access data on more than 16% of the devices outright. A further 74% contained data that could be recovered using file-carving methods. Only 11% of devices had been wiped properly.

The data recovered ranged from the harmless to revealing and even dangerous: calendar entries, meeting notes, access data for corporate resources, internal business documents, personal photos, medical information, tax documents and more. Some of the data could be used directly – for example, contact information, tax documents and medical records (or access to them through saved passwords). Other data could lead to indirect damage if exploited by cybercriminals.

Aside from the data that could be exposed, there’s also a risk that malware left on a device could infect the new owner. We found malware on 17% of the devices we looked at.

Sellers need to consider what traces they might leave behind when they sell a device; and buyers need to think about the security of any secondhand device they buy.

The UK National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) provides good practical advice for buyers and sellers.

Stalkerware during the pandemic

Stalkerware is commercially available software used to spy on another person via their device, without that person’s knowledge or consent. Stalkerware is the digital tip of a very real-world iceberg. In a 2017 report, the European Institute for Gender Equality indicates that seven out of 10 women affected by online stalking have experienced physical violence at the hands of the perpetrator. The Coalition Against Stalkerware defines stalkerware as software which “may facilitate intimate partner surveillance, harassment, abuse, stalking, and/or violence”.

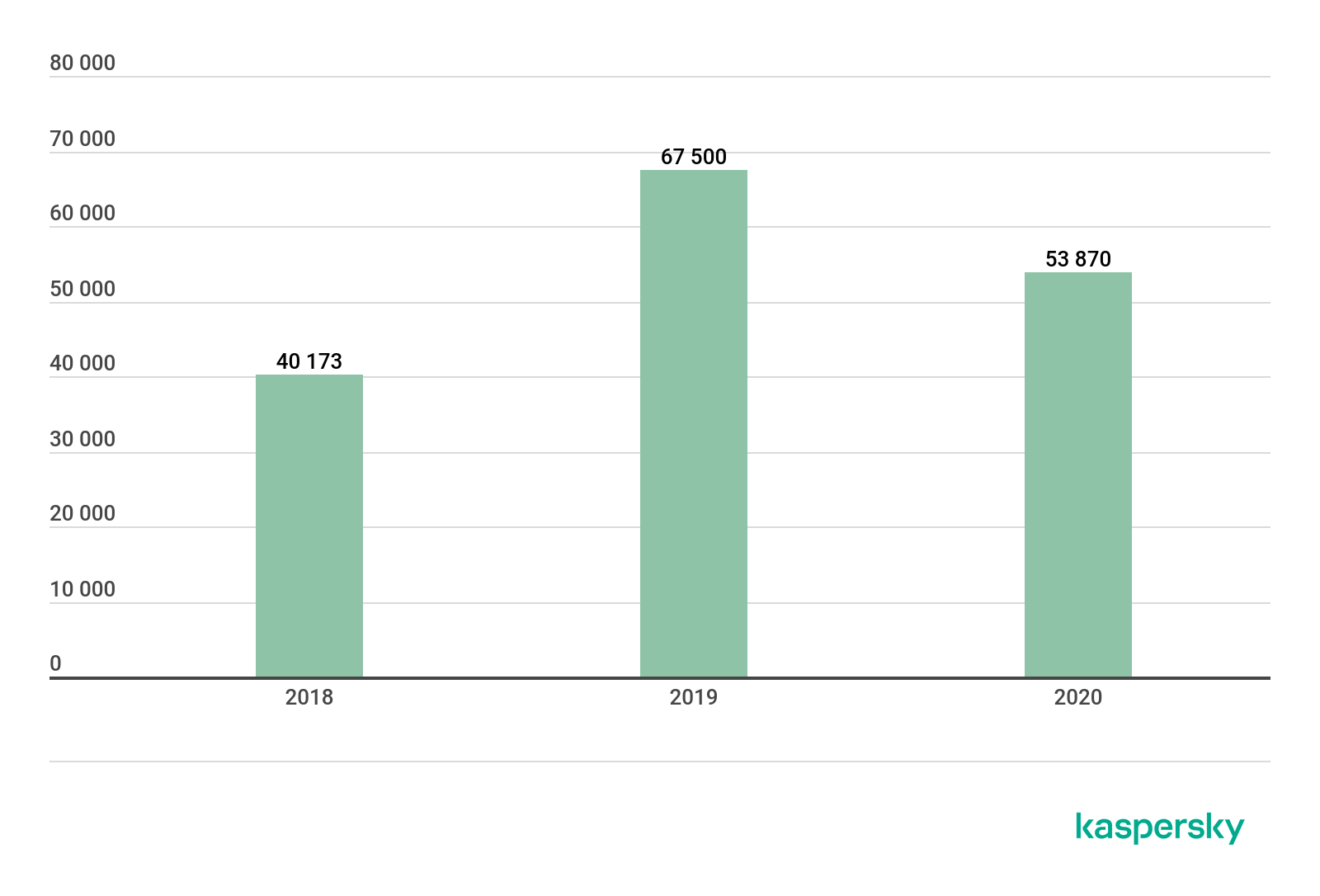

The number of people affected by stalkerware has been growing in recent years. We saw a fall in numbers in 2020, the drop-off coinciding with the worldwide lockdowns that came in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is hardly surprising: since stalking is typically carried out by someone the target lives with, if both abuser and target are housebound, there is less need to use technology to track someone’s activities. Notwithstanding the relative decline, 53,870 is a big number. Moreover, these are numbers of Kaspersky customers: no doubt the real figure is considerably higher.

The most commonly detected stalkerware sample in 2020 was Monitor.AndroidOS.Nidb.a. This app is re-sold under other names, so it is prominent in the market – iSpyoo, TheTruthSpy and Copy9 apps are all part of this family. Another popular application is Cerberus, which is sold as anti-theft smartphone protection and hides itself to avoid notice. Like genuine phone-finding apps, Cerberus has access to geo-location, can take photos and screenshots and record sound. Other high-ranking stalking apps include Track My Phone (which we detect as Agent.af), MobileTracker and Anlost.

The most commonly detected stalkerware sample in 2020 was Monitor.AndroidOS.Nidb.a. This app is re-sold under other names, so it is prominent in the market – iSpyoo, TheTruthSpy and Copy9 apps are all part of this family. Another popular application is Cerberus, which is sold as anti-theft smartphone protection and hides itself to avoid notice. Like genuine phone-finding apps, Cerberus has access to geo-location, can take photos and screenshots and record sound. Other high-ranking stalking apps include Track My Phone (which we detect as Agent.af), MobileTracker and Anlost.

Top 10 most detected stalkerware samples globally

| Samples | Affected users | |

| 1 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Nidb.a | 8147 |

| 2 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Cerberus.a | 5429 |

| 3 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Agent.af | 2727 |

| 4 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Anlost.a | 2234 |

| 5 | Monitor.AndroidOS.MobileTracker.c | 2161 |

| 6 | Monitor.AndroidOS.PhoneSpy.b | 1774 |

| 7 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Agent.hb | 1463 |

| 8 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Cerberus.b | 1310 |

| 9 | Monitor.AndroidOS.Reptilic.a | 1302 |

| 10 | Monitor.AndroidOS.SecretCam.a | 1124 |

The greatest number of stalkerware detections occurred in Russia, Brazil and the US.

Top 10 most affected countries by stalkerware – globally

| Country | Affected users | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 12389 |

| 2 | Brazil | 6523 |

| 3 | United States of America | 4745 |

| 4 | India | 4627 |

| 5 | Mexico | 1570 |

| 6 | Germany | 1547 |

| 7 | Iran | 1345 |

| 8 | Italy | 1144 |

| 9 | United Kingdom | 1009 |

| 10 | Saudi Arabia | 968 |

You can read our full report on the subject here.

Stalkerware operates stealthily, so it’s difficult for anyone targeted with such programs to see that it’s installed on their device – they hide the app’s icon and remove other traces of their presence.

Kaspersky is actively working to end the use of stalkerware, not just by detecting it but by working with partners. In 2019, Kaspersky and nine other founding members created the Coalition Against Stalkerware. Last year, we created TinyCheck, a free tool to detect stalkerware on mobile devices – specifically for service organizations working with people facing domestic violence. We are one of five partners in an EU-wide project aimed at tackling gender-based cyber-violence and stalkerware called DeStalk, which the European Commission chose to support with its Rights, Equality and Citizenship Program.

Doxing in the corporate sector

When most people think of doxing, they tend to think it applies only to celebrities and other high-profile people. However, confidential corporate information is no less sensitive; and the financial and reputational impact resulting from the disclosure of such data means that any organization could become a victim of doxing. This is clear, for example, from the fact that several ransomware gangs now threaten to leak stolen corporate data to increase the likelihood that their victims will pay up.

Cybercriminals use a variety of methods to gather confidential corporate information.

One of the easiest approaches is to use open-source intelligence (OSINT) – that is, gathering data from publicly accessible sources. The internet provides a lot of helpful information to would-be attackers, including the names and positions of employees, including those who occupy key positions in the company: for example, the CEO, HR director and chief financial officer.

Information harvested from the online personal profiles of employees can be used to set up BEC (Business Email Compromise) attacks, in which an attacker initiates email correspondence with a member of staff by posing as a different employee (including their superior) or as a representative of a partner company. The attacker does this to gain the trust of the target before persuading them to perform certain actions, such as sending confidential data or transferring funds to an account controlled by the attacker.

BEC attacks can also be used to collect further information about the company, or to gain access to valuable corporate data, or access to company resources – for example, credentials allowing access to cloud-based systems.

There are various technical tricks that cybercriminals use to obtain information relevant to their particular goals, including sending email messages containing a tracking pixel – often disguised as a “test” message.

This enables attackers to obtain data such as the time the email was opened, the version of the recipient’s mail client and the IP address. This data lets the attackers build a profile on a specific person who they can then impersonate in subsequent attacks.

Phishing continues to be an effective way for attackers to gather corporate data. For example, they may send an employee a message that mimics a notification from a business platform such as SharePoint, which contains a link.

If the employee clicks the link, they are redirected to a spoofed website containing a fraudulent form for entering their corporate account credentials – data which is captured by the attackers.

Sometimes cybercriminals resort to phone phishing – either by calling an employee directly and trying to “phish” corporate information, or sending a message and asking them to call the number given in the message. One way to trick employees is to pose as IT support staff – this method was used in the Twitter hack in July 2020.

By obtaining employee credentials, they were able to target specific employees who had access to our account support tools. They then targeted 130 Twitter accounts – Tweeting from 45, accessing the DM inbox of 36, and downloading the Twitter Data of 7.

— Twitter Support (@TwitterSupport) July 31, 2020

Attackers may not confine themselves to gathering publicly available data, but may also hack an employee’s account. This could be used to gain a foothold in the company, from which they can extend their activities, or to circulate false information that could damage the company’s reputation and result in financial loss. There has even been a case where cybercriminals have obtained audio and video content of the CEO of an international company and used deepfake technology to imitate the CEO’s voice, using it to persuade the management team of one of the company’s branches to transfer money to the scammers.

You can read our full report on doxing, including tips on how to protect yourself, here.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh