2021-09-30 19:00:49 Author: securelist.com(查看原文) 阅读量:51 收藏

![]() Download GhostEmperor’s technical details (PDF)

Download GhostEmperor’s technical details (PDF)

While investigating a recent rise of attacks against Exchange servers, we noticed a recurring cluster of activity that appeared in several distinct compromised networks. This cluster stood out for its usage of a formerly unknown Windows kernel mode rootkit that we dubbed Demodex, and a sophisticated multi-stage malware framework aimed at providing remote control over the attacked servers.

The former is used to hide the user mode malware’s artefacts from investigators and security solutions, while demonstrating an interesting undocumented loading scheme involving the kernel mode component of an open-source project named Cheat Engine to bypass the Windows Driver Signature Enforcement mechanism.

In an attempt to trace the duration of the observed attacks, we were able to see the toolset in question being used from as early as July 2020. Furthermore, we could see that the actor was mostly focused on South East Asian targets, with outliers in Egypt, Afghanistan and Ethiopia which included several governmental entities and telecommunication companies.

With a long-standing operation, high profile victims, advanced toolset and no affinity to a known threat actor, we decided to dub the underlying cluster GhostEmperor. Our investigation into this activity leads us to believe that the underlying actor is highly skilled and accomplished in their craft, both of which are evident through the use of a broad set of unusual and sophisticated anti-forensic and anti-analysis techniques.

How were the victims initially infected?

We identified multiple attack vectors that triggered an infection chain leading to the execution of malware in memory. We noticed that the majority of the GhostEmperor infections were deployed on public facing servers, as many of the malicious artefacts were installed by the ‘httpd.exe’ Apache server process, the ‘w3wp.exe’ IIS Windows server process, or the ‘oc4j.jar’ Oracle server process. This means that the attackers likely abused vulnerabilities in the web applications running on those systems, allowing them to drop and execute their files.

It is worth mentioning that one of the GhostEmperor infections affected an Exchange server, and took place on March 4, 2021. This was only two days after the patch for the ProxyLogon vulnerability was released by Microsoft, and it is possible that the attackers exploited this vulnerability in order to allow them to achieve remote code execution on vulnerable Exchange servers.

Although GhostEmperor’s infections often start with a BAT file, in some cases the known infection chain was preceded by an earlier stage: a malicious DLL that was side-loaded by wdichost.exe, a legitimate command line utility by Microsoft originally called MpCmdRun.exe. The side-loaded DLL then proceeds to decode and load an additional executable called license.rtf. Unfortunately, we did not manage to retrieve this executable, but we saw that the consecutive actions of loading it included the creation and execution of GhostEmperor scripts by wdichost.exe.

Example of a GhostEmperor infection chain started by a side-loaded DLL

Lastly, some of the Demodex deployments were performed remotely from another system in the network using legitimate tools such as WMI or PsExec, suggesting that the attackers have infected parts of the victims’ networks beforehand.

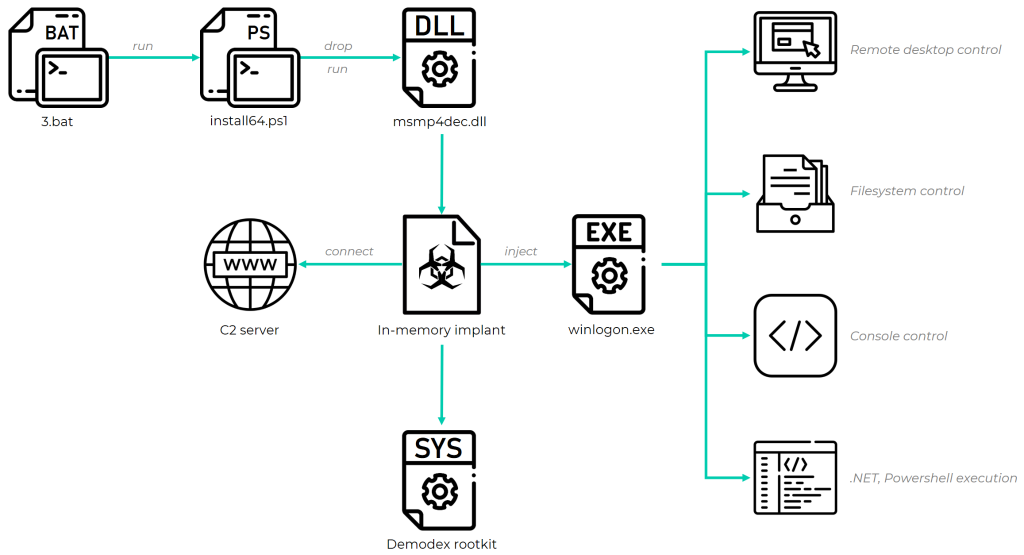

Infection chain overview

The infection can be divided into several stages that operate in succession to activate an in-memory implant and allow it to deploy additional payloads during run time. This section provides a brief overview of these stages, including a description of the final payloads. The internals of these payloads can be found in a technical document that accompanies this publication.

The flow of infection starts with a PowerShell dropper. The purpose of this component is to stage the subsequent element in the chain by installing it as a service. Before doing so, it creates a couple of registry keys that it assigns encrypted data to, one of which corresponds to a payload that will be deployed in the later stages. It’s worth noting that the script itself is delivered in a packed form, whereby its complete execution is dependent on a command-line argument that is used as a key to decrypt the bulk of its logic and data. Without this key, it’s impossible to recover the flow that comes after this stage.

Initial stage comprised of encrypted PowerShell code that is decrypted based on an attacker-provided AES key during run time

The next stage, which is executed as a service by the former, is intended to serve as yet another precursor for the next phases. It is used to read the encrypted data from the previously written registry keys and decrypt it to initiate the execution of an in-memory implant. We identified two variants of this component, one developed in C++ and another in .NET. The latter, which appeared in the wild as early as March 2021, uses the GUID of the infected machine to derive the decryption key, and is thus tailored to be executed on that specific system. The C++ variant, on the other hand, relies on hardcoded AES 256 encryption keys.

The third stage is the core implant that operates in memory after being deployed by the aforementioned loader, and is injected into the address space of a newly created svchost.exe process. Its main goal is to facilitate a communication channel with a C2 server, whereby malicious traffic is masqueraded under the guise of communication with a benign service, based on a Malleable C2 profile embedded within its configuration. It is important to note that the implementation of the Malleable C2 feature, which is originally provided in the Cobalt Strike framework, is customized and most likely rewritten based on reverse engineering of Cobalt Strike’s code.

Another interesting technique used to conceal the malicious traffic is the malware’s usage of fake file format headers to encapsulate the data passed to the C&C server. To do so, the in-memory implant synthesizes a fake media file of one of the formats RIFF, JPEG or PNG and puts any data conveyed to the server in encrypted form as its body. Thus, the transmitted packet appears as either an image or audio file and blends with other legitimate traffic in the network.

Malleable C2 profile and fake header

The last stage is the payload injected to the winlogon.exe process by the aforementioned implant and used to provide remote control capabilities to the attackers. Such capabilities include initiation of a remote console or desktop session, with the latter supporting execution of sent mouse clicks and keystrokes on the target machine and retrieval of periodic screenshots that reflect the output of those actions. This stage can also allow the attackers to load arbitrary .NET assemblies or execute PowerShell commands, as well as fully control the victim’s filesystem in order to search, retrieve or push files to it.

In addition to the last stage payload, the core component is also capable of deploying a Windows kernel mode driver on the system. The purpose of this driver is to serve as a rootkit that conceals malware artefacts such as files, registry keys and network traffic, thus gaining stealth and ability to avoid detection by security products and forensic investigators. The upcoming sections elaborate on how this driver is deployed (namely how it bypasses Windows mitigations, given that it’s not digitally signed) and what particular features it provides to the user mode malicious implant.

Overview of the GhostEmperor infection chain

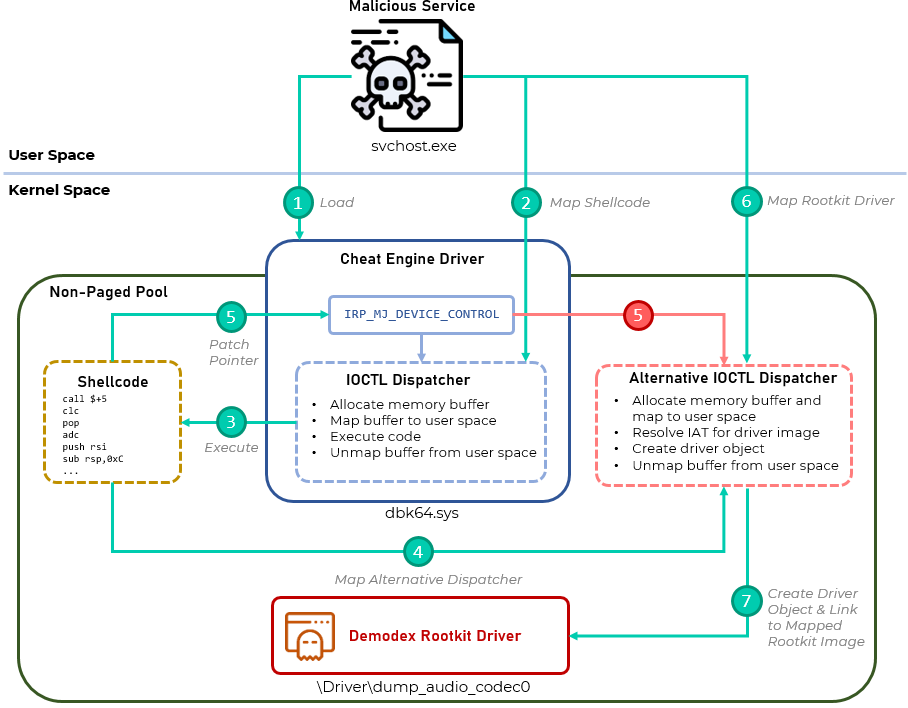

Rootkit loading analysis

On modern 64-bit Windows operating systems, it is generally not possible to load an unsigned driver in a documented way due to the Driver Signature Enforcement mechanism introduced by Microsoft. For this reason, attackers have abused vulnerabilities in signed drivers to allow execution of unsigned code to kernel space. A typical approach1 taken by many actors to date, and mostly in older versions of Windows, is to disable the Code Integrity mechanism by switching the nt!g_CiEnabled flag that resides within the CI.DLL kernel module after getting write and execution primitives via vulnerable signed drivers. After shutting down the Code Integrity mechanism, an unsigned driver can be loaded.

This approach was limited by Microsoft with the introduction of Kernel Patch Protection (a.k.a PatchGuard). This mechanism protects modification of specific data structures in the Windows kernel memory space, including the nt!g_CiEnabled flag. For this reason, the modification of this flag can now cause an invocation of a BSOD. This can be tackled by quickly setting the flag value, loading an unsigned driver and switching it back to the previous state before PatchGuard identifies a change, though this still introduces a race condition that can crash the system.

The approach used by the developer of this rootkit allows loading an unsigned driver without modifying the Code Integrity image and dealing with a potential crash. It abuses features of a legitimate and open-source2 signed driver named dbk64.sys which is shipped along with Cheat Engine, an application created to bypass video game protections and introduce cheats into them. This driver provides capability to write and execute code in kernel space by design, thus allowing it to run arbitrary code in kernel mode.

After dropping the dbk64.sys driver with a randomly generated filename to disk and loading it, the malware issues documented3 IOCTLs to the driver that allow shellcode to be run in kernel space through the following sequence of actions:

- First, a memory buffer is allocated in the kernel space non-paged pool by issuing IOCTL_CE_ALLOCATEMEM_NONPAGED.

- A successfully allocated memory buffer will be then shared between the user mode malware process and kernel address spaces using a direct I/O approach, whereby the kernel mode buffer’s address is mapped to a different address in user space. This is achieved by locking the buffer’s pages in physical memory so that they cannot be paged out (which is possible since they are allocated in the non-paged pool) following which an MDL for the buffer is created and a call to the MmMapLockedPagesSpecifyCache API function is made. All of this is implemented in the handler of IOCTL_CE_MAP_MEMORY.

- At this point the malware can access the buffer in user mode through the provided pointer from the previous IOCTL and write to it. The written data will in turn be reflected in the same buffer in kernel space. This is used to write the shellcode into the buffer.

- After the writing is done, the buffer is unmapped from user space by issuing IOCTL_CE_UNMAP_MEMORY.

- The written shellcode now resides only in kernel space and can be run by issuing IOCTL_CE_EXECUTE_CODE.

The purpose of the shellcode is to replace the dbk64.sys IOCTL dispatcher with an alternative one that in turn allows the loading of an unsigned driver. The alternative dispatcher is also implemented as position-independent code and is bundled with the shellcode. To replace the original dispatcher, the shellcode maps the code of the new dispatcher in memory and patches the pointer to the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL routine in the dbk64.sys driver object. At this point, the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL pointer is set to the new dispatcher’s address and any IOCTL issued to the driver will pass through it.

IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONROL hooking

The alternative dispatcher provides the same core capabilities as the original one, with the addition of a few that allow it to load a new driver to kernel space. The functionality that makes it possible to achieve this goal is exposed through a set of IOCTL handlers that are called in succession, finally leading to the load of the malware’s kernel mode rootkit. Below is a table of these IOCTLs with descriptions, arranged in the order they are invoked by the malware’s user mode logic in charge of deploying the rootkit.

| IOCTL Code | Description |

| 0x220180 | Processes a buffer provided by the user mode malware component by verifying its size is 272 bytes and then decodes it by negating its bytes. This IOCTL is in fact not invoked by the user mode code. |

| 0x220184 | Allocates a buffer in kernel space, locks its pages, creates an MDL and maps the buffer to a user mode address using the MmMapLockedPagesSpecifyCache API. This is essentially equivalent to the chaining of functionalities in IOCTL_CE_ALLOCATEMEM_NONPAGED and IOCTL_CE_MAP_MEMORY from the original dispatcher. After this call, the user mode code has access to a kernel mode buffer and can write to it using a pointer in user mode, as was the case for writing the shellcode. This time, however, the malware manually loads the rootkit’s PE image into the allocated buffer. |

| 0x2201B4 | Since the malware’s user mode code is in charge of loading the rootkit’s image manually in IOCTL 0x220184, it has to resolve some function addresses in kernel space that appear as dependencies in the image’s Import Address Table. This IOCTL allows the function names to be received from user space as strings, retrieving their address with the MmGetSystemRoutineAddress API and providing it back to the user mode code. The latter places the resolved address in the corresponding IAT entry of the loaded image. |

| 0x220188 | Unmaps the address of the kernel mode buffer from user space so it’s only accessible through its kernel mode pointer. |

| 0x2201B8 | Creates a new driver object using the IoCreateDriver function, assigning the driver initialization function pointer to a position-independent stub that is delivered with the shellcode and, once invoked, calls the loaded rootkit’s DriverEntry function. |

It is worth mentioning that the malware’s service makes use of a Cheat Engine utility called kernelmoduleuloader.exe (MD5: 96F5312281777E9CC912D5B2D09E6132) during the loading of the dbk64.sys driver. The driver is dropped along with the utility and a .sig file, with the latter being used as a means of authenticating the component calling dbk64.sys by conveying a digital signature that is associated with its binary.

As the malware is not a component of Cheat Engine, it runs kernelmoduleunloader.exe as a new process and injects it with a small shellcode that merely opens a handle to the dbk64.sys device with the CreateFileW API. The value of the handle is written as the second QWORD in the injected buffer, read by the malware’s process and gets duplicated using the DuplicateHandle API. From this point on, the malware’s service can call the driver as if it was a signed Cheat Engine component.

An outline of the rootkit’s loading phases

Demodex rootkit functionality

The loaded rootkit, which we dubbed Demodex, serves the purpose of hiding several artefacts of the malware’s service. This is achieved through a set of IOCTLs exposed by the rootkit’s driver that are in turn called by the service’s user mode code, each disguising a particular malicious artefact. To access the rootkit’s functionality, the malware ought to obtain a handle to the corresponding device object, after which the following IOCTLs are available for further use:

- 0x220204: Receives an argument with the PID of the svchost.exe process which runs the code of the malicious service and stores it within a global variable. This variable is used by other IOCTLs later on.

- 0x220224: Initializes global variables that are later used to hold data such as the aforementioned svchost.exe PID, the name of the malware’s service, the path to the malware’s DLL and a network port.

- 0x220300: Hides the malware’s service from a list within the services.exe process address space. The service’s name is passed as an argument to the IOCTL, in turn being sought in a system-maintained linked list. The corresponding entry is being unlinked, thus hiding the service from being easily detected. The logic in this handler is reminiscent of the technique outlined here.

- 0x220304: This IOCTL is used to register a file system filter driver’s notification routine by using the IoRegisterFSRegistrationChange API. The notification routine invoked upon registration of a new file system verifies if it is an NTFS-based one and if so, creates a device object for the rootkit which is attached to the subject file system’s device stack. Additionally, both the file system’s device object and the associated rootkit device object are registered in a global list maintained by the rootkit’s driver. Subsequent attempts to retrieve information from, access or modify the file will fail and generate error codes such as STATUS_NO_MORE_FILES or STATUS_NO_SUCH_FILE.

- 0x220308: Hides TCP connections that make use of ports within a given range from utilities that list them, such as netstat. This is done through a known4 method whereby the IOCTL dispatch routine of the NSI proxy driver is hooked and the completion routine is set to one that inspects the port of a given connection. If the underlying connection’s port falls within the given range, its entry is removed from the system’s TCP table. The two ports that constitute the range are passed as arguments to the IOCTL.

- 0x22030C: Hides malware-related registry keys by hooking several registry operations through the CmRegisterCallback API. The registered callback checks the type of operation and acts according to the following logic:

- For operations of the type RegNtPostEnumerateKey or RegNtPostEnumerateValueKey (enumeration of a key or subkey) it verifies if there is an attempt to enumerate the driver related key under HKLM\SYSTEM\ControlSet0**\Services\<malware_service_name> and if so, sets the return status of the operation to STATUS_NO_MORE_ENTRIES in order to indicate there is no data to provide for the requested enumeration.

- For operations of the type RegNtPreOpenKeyEx (attempt to open a key) on SOFTWARE\Microsoft\{EAAB20A7-9B68-4185-A447-7E4D21621943} it clears all the driver’s internal global variables, which is equivalent to resetting its operation. That’s because this key is used by the malware’s uninstaller PowerShell script, mentioned in previous sections.

- For any attempt to change a key under HKLM\MACHINE\SYSTEM via an operation with code RegNtPreSaveKey or lower, it sets that return status to the application error 0xC0000043.

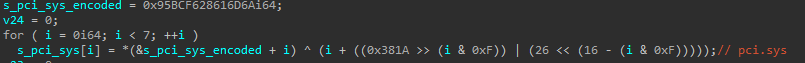

Interestingly, the pointer passed to CmRegisterCallback does not contain the direct address of the function handling the logic above, but instead an address at the end of the executable section of the pci.sys driver’s image, which is originally filled with zeros as a means to align the section in memory. Before passing the callback pointer to CmRegisterCallback, such a section is sought within the pci.sys driver and the corresponding bytes within it are patched so as to invoke the call to the actual callback handling the above logic, as outlined below. This allows all intercepted registry operations to appear as if they are handled by code that originates in the legit pci.sys driver.

Code used to patch a section in the pci.sys image in memory in order to write it with a short shellcode stub that jumps into a registry inspection callback

It is worth mentioning that the Demodex rootkit supports Windows 10 by design, and indeed appears to work according to our tests on Windows 10 builds. This is evident in the driver’s code in multiple places where different flows of the code are taken based on the underlying operating system’s version. In such checks it is possible to observe that some flows correspond to the latest builds of Windows 10, as outlined in the code snippet below.

Obfuscation and anti-analysis methods

The authors of the malware components used in the GhostEmperor cluster of activity have made some development choices that have implications on the forensic analysis process. To demonstrate some of the hurdles that investigators face, we will limit the discussion to two common analysis tools – WinDbg and Volatility. Other tools may encounter similar drawbacks when dealing with the implants in question.

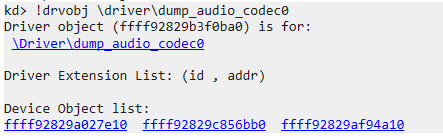

First, due to the way Demodex is loaded, its driver is not properly enlisted in WinDbg along with other system modules that are loaded in a documented way. That said, it is still possible to find the rootkit’s driver object by referring to its name (\driver\dump_audio_codec0), thus being able to list its associated device objects as well:

Driver object name listed in WinDBG

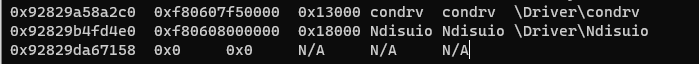

Similarly, when trying to list system modules with the Volatility3 widows.driverscan module, the Demodex driver is absent from the output. However, the framework does indicate that an anomaly is detected in the process of scanning the kernel’s memory space in search for the driver:

Anomaly while listing the Demodex driver with the windows.driverscan Volatility3 module

In addition, the malware authors have made a deliberate choice to remove all PE headers from memory-loaded images in both the third stage of the malware and the rootkit’s driver. This is done by either introducing the image with a zeroed-out header to begin with (as is the case in the third stage) and relying on a custom loader to prepare it for execution or by replacing the header of the image after its loaded with the 0x00 value, as is the case with the rootkit’s driver. From a forensic perspective, this impedes the process of identifying PE images loaded to memory by searching for their headers.

As mentioned in previous sections, the developers implemented a trampoline within the pci.sys legitimate driver in order to mask the source of callbacks that are invoked for registry-related operations. Thus, analysts that try to track such callbacks may miss out on some because they will appear to be benign calls. As demonstrated in the WinDbg listing of the Cm* callbacks below, one of them is associated with the symbol pci!ArbLibraryDeinitialize+0xa4; however, if we look at the code at the same address we can see that it is in fact a small piece of shellcode emitted by the rootkit in order to jump to the actual malicious callback that hides the malware’s registry keys.

Listing of Cm* callbacks and shellcode found within a seemingly benign code invoked from the pci.sys driver

Apart from the above, the developers introduced more standard methods of obfuscation that typically slow the static analysis of the code and are evident across multiple malware components. An example of this is a pattern of string obfuscation whereby each string is decoded with a set of predefined arithmetic and logic operations, such that different operands (e.g., shift offsets) are chosen for each string. This suggests that each string is obfuscated during compilation and that the authors have established a form of SDK that aids in uniquely obfuscating each sample during build time.

String decoding logic used to obtain clear-text strings from hardcoded blobs through a set of arithmetic and logic operations

Similarly, it is possible to observe multiple instances of API call obfuscation in the code. This is done by replacing inline calls to API functions with other stub functions that build the requested API name as a stack string, resolve it using GetProcAddress and call it while passing the arguments provided in a special struct to the stub function. The struct has a bigger size than required to pass the argument data, and most of it is filled with junk, such that only particular fields have meaningful data that gets encoded before being passed to the stub. Those fields get decoded within the stub function and in turn passed to the API function.

Example of a stub used for API call obfuscation

It is worth noting that as in the case of string obfuscation, each stub is uniquely built and makes use of an argument struct of a different size where the fields that are occupied with actual argument data are chosen at random. The order in which the stack string is initialized is also random and each stub function is used only once as a replacement for a single inline API function call. In other words, the same API function used in different places in the code will have different stubs for each place with different argument structs. This reinforces the observation that the authors were using a designated obfuscation SDK in which the API call obfuscation is yet another feature.

Finally, it is possible to see that some variants appeared in both obfuscated and non-obfuscated form. For example, we managed to view the C++ version of the second stage loader in two forms – one form that has no obfuscation at all and another that is heavily obfuscated (MD5: 18BE25AB5592329858965BEDFCC105AF). In the figure below we can see the same function in the two variants: one has the original flow of the code as produced by a compiler without obfuscation, while the other has its control flow flattened to the point where it is impossible to track the order of actions.

Example of the same function used in two variants of the second stage loader; one is non-obfuscated and the other’s control flow was flattened

Post-exploitation toolset

Once the attackers gain access to the compromised systems through the aforementioned infection chain, they use a mix of legitimate and open-source offensive toolsets to harvest user credentials and pivot to other systems in the network. This includes common utilities from the Sysinternals suite used to control processes (e.g., PsExec, PsList and ProcDump), as well as other tools like WinRAR, CertUtil and BITSAdmin. As for open-source tools, the attackers used tools such as mimkat_ssp, Get-PassHashes.ps1, Token.exe and Ladon. Internal network reconnaissance and communication is often carried out by NBTscan and Powercat.

A more comprehensive outline of these tools along with the actual command lines used by the threat actor to operate them can be found in the supplementary technical document.

Network infrastructure

For C2 communication, the attackers registered domains whose names appear to have been randomly generated, potentially not to attract any attention to the malicious traffic. GhostEmperor mainly used hosting services based in Hong Kong and South Korea, such as Daou Technology or Anchent Asia Limited.

- newlylab[.]com

- reclubpress[.]com

- webdignusdata[.]com

- freedecrease[.]com

- aftercould[.]com

- datacentreonline[.]com

- newfreepre[.]com

We also observed additional IP addresses used for downloading some of the malicious samples, or for C2 communication by the in-memory implant:

- 223.135[.]214

- 148.165[.]158

- 102.114[.]55

- 102.113[.]57

- 102.113[.]240

Who were the targets?

The majority of GhostEmperor’s victims were government entities and telecommunication companies in South East Asia, with multiple high-profile entities targeted in Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. We also observed additional victims of a similar nature from countries such as Egypt, Ethiopia and Afghanistan. Even though the latter cluster of victims belongs to a different region from the one in which we saw GhostEmperor to be highly active, we noticed that some of the organizations within it have strong ties with countries in South East Asia. This means that the attackers might have leveraged those infections to spy on the activities in countries that are of geopolitical interest to them.

Who is behind the attacks?

We attribute this activity to a formerly unknown Chinese-speaking threat actor. This is due to the fact that the attackers made use of open-source tools such as Ladon or Mimikat_ssp that are popular among such actors, with additional data points such as version info found within the resource section of second stage loader binaries that included a legal trademark field with a Chinese character: ‘Windows庐 is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation.’

Version info of loader binary with a Chinese character

On the same note, we observed that one of the decryption keys provided in a command line by the attackers and used to decode the first stage PowerShell scripts was ‘wudi520’. Looking it up in publicly available sources led us to a GitHub account under the same name. Although we cannot confirm this account is indeed connected to the GhostEmperor attackers, it has forked multiple code repositories with descriptions in Chinese or that are otherwise authored by Chinese-speaking developers.

“wudi520” GitHub account

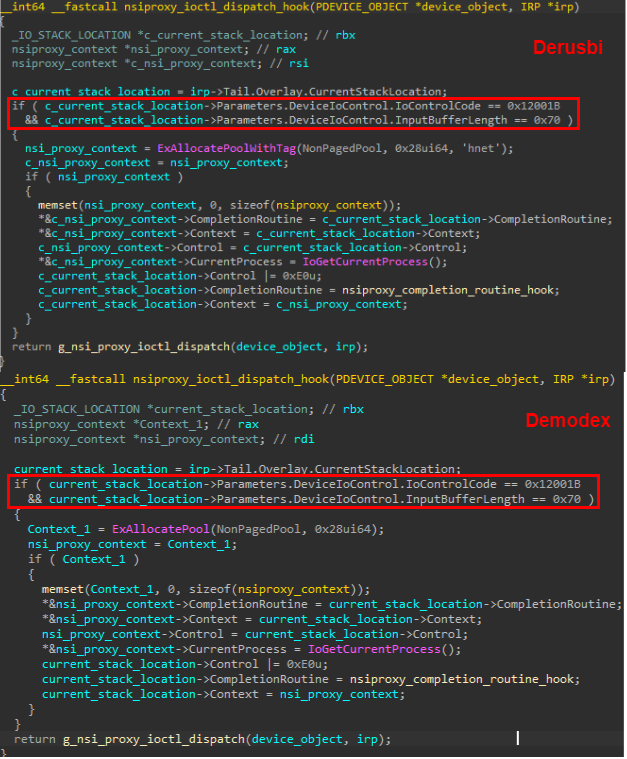

In addition, we noticed some similarities between the features of Demodex and those of the Derusbi rootkit, which was publicly described in the past and also attributed to a Chinese-speaking actor. The purpose of both is to hide malicious artefacts, where notably both have an almost identical flow for hiding TCP connections by hooking the nsiproxy.sys IOCTL dispatcher. The implementation of this filtering in the Demodex sample we analyzed is nearly identical to one seen in an older Derusbi sample (MD5: 24E9870973CEA42E6FAF705B14208E52) to the point that both use the same device control code for this action and receive an IOCTL input of the same size. That said, it is worth noting that while Derusbi used a hardcoded range of 1025 to 1777 for the targeted ports to hide, Demodex allows for an arbitrary range that can be configured by the attackers through the user mode malware.

Comparison of a similar IOCTL in the Demodex and Derusbi rootkits

It is worth noting that in one of the victim systems we observed two instances of malicious samples being dropped via a web shell. One led to the initiation of an infection chain consisting of the first stage PowerShell dropper and second stage .NET service DLL, and another was a drop of two binaries5 of the Netbot malware, formerly seen being used6 by the Lucky Mouse group. Though we cannot attest to the fact that the very same web shell was used to drop both files, the proximity of events which occurred in the course of two days, may suggest that underlying actor indeed deployed both samples and that it has a possible connection to the Lucky Mouse group, whether through shared development resources or reused tools.

Conclusions

GhostEmperor is an example of an advanced threat actor that goes after prominent targets and aims to maintain a long standing and persistent operation within their environments. We observed that the underlying actor managed to remain under the radar for months, all the while demonstrating a finesse when it came to developing the malicious toolkit, a profound understanding of an investigator’s mindset and the ability to counter forensic analysis in various ways.

Additionally, while rootkits are generally considered a deprecated method of attack, this case and other recent ones show that with a creative approach they can still be leveraged to gain a considerable level of stealth. As we have seen, the attackers conducted the required level of research to make the Demodex rootkit fully functional on Windows 10, allowing it to load through documented features of a third-party signed and benign driver. This suggests that rootkits still need to be taken into account as a TTP during investigations and that advanced threat actors, such as the one behind GhostEmperor, are willing to continue making use of them in future campaigns.

Indicators of compromise

Stage 1 – PowerShell Dropper

012862165EC105A44FEA14FACE53492F – u_ex200822.ps1

Stage 2 – Service DLL

6A44FDD66AB841C33949620666CA847A – RAudioUniConfig.dll

2DD0885F84B890883A396030DB841D28

1BC301AA9B861F762CE5F376228E992A – svchosts.exe

Stage 4

0BBFBA106FBB9E310330DC87C32CB6D1 – Payload DLL

6685323C61D8EDB4A6E35796AF34D626 – Remote Desktop Control DLL

Post-exploitation

BE38D173E4E9118BDC2E83FD5F90BE3B – kekeo.exe

F078AC9B012C503D35254AF9629D3B67 – debugall.vbs

Driver

7394229455151a9cd036383027a1536b

File paths

C:\Windows\debug\wia

PDB paths

C:\c\getpwd\x64\Release\getpwd.pdb

D:\Source\workspace\ExCtrl\XControl\Release\XCLoader.pdb

Service name and DLL path

MsMp4Hw – C:\Windows\System32\msmp4dec.dll

Msdecode – C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\Network\Connections\msdecode.dll

AuthSvc – C:\Windows\System32\AuthSvc.dll

Registry keys for encrypted buffer

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\hiaudio

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\midihelp

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\data

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\update

Domains and IPs

imap.newlylab[.]com

mail.reclubpress[.]com

imap.webdignusdata[.]com

freedecrease[.]com

aftercould[.]com

datacentreonline[.]com

game.newfreepre[.]com

27.102.113[.]57

27.102.113[.]240

27.102.114[.]55

27.102.115[.]51

27.102.129[.]120

107.148.165[.]158

154.223.135[.]214

1 This approach is well documented and demonstrated in the DSEFix public repository: https://github.com/hfiref0x/DSEFix

2 The source code of the driver can be found on GitHub.

3 They are outlined in the IOPLDispatcher.c source code within the Cheat Engines repository.

4 A technique similar to the one observed in the Demodex rootkit is outlined in this code: https://github.com/bowlofstew/rootkit.com/blob/master/cardmagic/PortHidDemo_Vista.c

5 Those binaries had the MD5s: 145FF08E736693D522F8A09C8D3405D6, 7A162C26D56B0C55E6CD81CD953F510B

6 https://securelist.com/ksb-2019-review-of-the-year/95394/, detailed analysis of the Netbot malware as part of Lucky Mouse campaigns is available to customers of our APT reporting service.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh