2021-1-12 13:53:55 Author: blog.fox-it.com(查看原文) 阅读量:11 收藏

tl;dr

NCC Group and Fox-IT have been tracking a threat group with a wide set of interests, from intellectual property (IP) from victims in the semiconductors industry through to passenger data from the airline industry.

In their intrusions they regularly abuse cloud services from Google and Microsoft to achieve their goals. NCC Group and Fox-IT observed this threat actor during various incident response engagements performed between October 2019 until April 2020. Our threat intelligence analysts noticed clear overlap between the various cases in infrastructure and capabilities, and as a result we assess with moderate confidence that one group was carrying out the intrusions across multiple victims operating in Chinese interests.

In open source this actor is referred to as Chimera by CyCraft.

NCC Group and Fox-IT have seen this actor remain undetected, their dwell time, for up to three years. As such, if you were a victim, they might still be active in your network looking for your most recent crown jewels.

We contained and eradicated the threat from our client’s networks during incident response whilst our Managed Detection and Response (MDR) clients automatically received detection logic.

With this publication, NCC Group and Fox-IT aim to provide the wider community with information and intelligence that can be used to hunt for this threat in historic data and improve detections for intrusions by this intrusion set.

Throughout we use terminology to describe the various phases, tactics, and techniques of the intrusions standardized by MITRE with their ATT&CK framework . Near the end of this article all the tactics and techniques used by the adversary are listed with links to the MITRE website with more information.

In all the intrusions we have observed they are performed in similar ways by the adversary: from initial access all the way to actions on objectives. The objective in these cases appear to be stealing sensitive data from the victim’s networks.

Credential theft and password spraying to Cobalt Strike

This adversary starts with obtaining usernames and passwords of their victim from previous breaches. These credentials are used in a credential stuffing or password spraying attack against the victim’s remote services, such as webmail or other internet reachable mail services. After obtaining a valid account, they use this account to access the victim’s VPN, Citrix or another remote service that allows access to the network of the victim. Information regarding these remotes services is taken from the mailbox, cloud drive, or other cloud resources accessible by the compromised account. As soon as they have a foothold on a system (also known as patient zero or index case), they check the permissions of the account on that system, and attempt to obtain a list of accounts with administrator privileges. With this list of administrator-accounts, the adversary performs another password spraying attack until a valid admin account is compromised. With this valid admin account, a Cobalt Strike beacon is loaded into memory of patient zero. From here on the adversary stops using the victim’s remote service to access the victim’s network, and starts using the Cobalt Strike beacon for remote access and command and control.

Network discovery and lateral movement

The adversary continues their discovery of the victim’s network from patient zero. Various scans and queries are used to find proxy settings, domain controllers, remote desktop services, Citrix services, and network shares. If the obtained valid account is already member of the domain admins group, the first lateral move in the network is usually to a domain controller where the adversary also deploys a Cobalt Strike beacon. Otherwise, a jump host or other system likely used by domain admins is found and equipped with a Cobalt Strike beacon. After this the adversary dumps the domain admin credentials from the memory of this machine, continues lateral moving through the network, and places Cobalt Strike beacons on servers for increased persistent access into the victim’s network. If the victim’s network contains other Windows domains or different network security zones, the adversary scans and finds the trust relationships and jump hosts, attempting to move into the other domains and security zones. The adversary is typically able to perform all the steps described above within one day.

During this process, the adversary identifies data of interest from the network of the victim. This can be anything from file and directory-listings, configuration files, manuals, email stores in the guise of OST- and PST-files, file shares with intellectual property (IP), and personally identifiable information (PII) scraped from memory. If the data is small enough, it is exfiltrated through the command and control channel of the Cobalt Strike beacons. However, usually the data is compressed with WinRAR, staged on another system of the victim, and from there copied to a OneDrive-account controlled by the adversary.

After the adversary completes their initial exfiltration, they return every few weeks to check for new data of interest and user accounts. At times they have been observed attempting to perform a degree of anti-forensic activities including clearing event logs, time stomping files, and removing scheduled tasks created for some objectives. But this isn’t done consistently across their engagements.

Credential access (TA0006)

The earliest and longest lasting intrusion by this threat we observed, was at a company in the semiconductors industry in Europe and started early Q4 2017. The more recent intrusions took place in 2019 at companies in the aviation industry. The techniques used to achieve access at the companies in the aviation industry closely resembles techniques used at victims in the semiconductors industry.

The threat used valid accounts against remote services: Cloud-based applications utilizing federated authentication protocols. Our incident responders analysed the credentials used by the adversary and the traces of the intrusion in log files. They uncovered an obvious overlap in the credentials used by this threat and the presence of those same accounts in previously breached databases. Besides that, the traces in log files showed more than usual login attempts with a username formatted as email address, e.g.<username>@<email domain>. While usernames for legitimate logins at the victim’s network were generally formatted like <domain>\<username>. And attempted logins came from a relative small set of IP-addresses.

For the investigators at NCC Group and Fox-IT these pieces of evidence supported the hypothesis of the adversary achieving credentials access by brute force, and more specifically by credential stuffing or password spraying.

Initial access (TA0001)

In some of the intrusions the adversary used the valid account to directly login to a Citrix environment and continued their work from there.

In one specific case, the adversary now armed with the valid account, was able to access a document stored in SharePoint Online, part of Microsoft Office 365. This specific document described how to access the internet facing company portal and the web-based VPN client into the company network. Within an hour after grabbing this document, the adversary accessed the company portal with the valid account.

From this portal it was possible to launch the web-based VPN. The VPN was protected by two-factor authentication (2FA) by sending an SMS with a one-time password (OTP) to the user account’s primary or alternate phone number. It was possible to configure an alternate phone number for the logged in user account at the company portal. The adversary used this opportunity to configure an alternate phone number controlled by the adversary.

By performing two-factor authentication interception by receiving the OTP on their own telephone number, they gained access to the company network via the VPN. However, they also made a mistake during this process within one incident. Our hypothesis is that they tested the 2FA-system first or selected the primary phone number to send a SMS to. However the European owner of the account received a text message with Simplified Chinese characters on the primary phone number in the middle of the night Eastern European Time (EET). NCC Group and Fox-IT identified that the language in the text-message for 2FA is based on the web browser’s language settings used during the authentication flow. Thus the 2FA code was sent with supporting Chinese text.

Account discovery (T1087)

With access into the network of the victim, the adversary finds a way to install a Cobalt Strike beacon on a system of the victim (see Execution). But before doing so, we observed the adversary checking the current permissions of the obtained user account with the following commands:

net user

net user Administrator

net user <username> /domain

net localgroup administratorsIf the user account doesn’t have local administrative or domain administrative permissions, the adversary attempts to discover which local or domain admin accounts exist, and exfiltrates the admin’s usernames. To identify if privileged users are active on remote servers, the adversary makes use of PsLogList from Microsoft Sysinternals to retrieve the Security event logs. The built-in Windows quser-command to show logged on users is also heavily used by them. If such a privileged user was recently active on a server the adversary executes Cobalt Strike’s built-in Mimikatz to dump its password hashes.

Privilege escalation (TA0004)

The adversary started a password spraying attack against those domain admin accounts, and successfully got a valid domain admin account this way. In other cases, the adversary moved laterally to another system with a domain admin logged in. We observed the use of Mimikatz on this system and saw the hashes of the logged in domain admin account going through the command and control channel of the adversary. The adversary used a tool called NtdsAudit to dump the password hashes of domain users as well as we observed the following command:

msadcs.exe "NTDS.dit" -s "SYSTEM" -p RecordedTV_pdmp.txt --users-csv RecordedTV_users.csvNote: the adversary renamed ntdsaudit.exe to msadcs.exe.

But we also observed the adversary using the tool ntdsutil to create a copy of the Active Directory database NTDS.dit followed by a repair action with esentutl to fix a possible corrupt NTDS.dit:

ntdsutil "ac i ntds" "ifm" "create full C:\Windows\Temp\tmp" q q

esentutl /p /o ntds.ditBoth ntdsutil and esentutl are by default installed on a domain controller.

A tool used by the adversary which wasn’t installed on the servers by default, was DSInternals. DSInternals is a PowerShell module that makes use of internal Active Directory features. The files and directories found on various systems of a victim match with DSInternals version 2.16.1. We have found traces that indicate DSInternals was executed and at which time, which match with the rest of the traces of the intrusion. We haven’t recovered traces of how the adversary used DSInternals, but considering the phase of the intrusion the adversary used the tool, it is likely they used it for either account discovery or privilege escalation, or both.

Execution (TA0002)

The adversary installs a hackers best friend during the intrusion: Cobalt Strike. Cobalt Strike is a framework designed for adversary simulation intended for penetration testers and red teams. It has been widely adopted by malicious threats as well.

The Cobalt Strike beacon is installed in memory by using a PowerShell one-liner. At least the following three versions of Cobalt Strike have been in use by the adversary:

- Cobalt Strike v3.8, observed Q2 2017

- Cobalt Strike v3.12, observed Q3 2018

- Cobalt Strike v3.14, observed Q2 2019

Fox-IT has been collecting information about Cobalt Strike team servers since January 2015. This research project covers the fingerprinting of Cobalt Strike servers and is described in Fox-IT blog “Identifying Cobalt Strike team servers in the wild”. The collected information allows Fox-IT to correlate Cobalt Strike team servers, based on various configuration settings. Because of this, historic information was available during this investigation. Whenever a Cobalt Strike C2 channel was identified, Fox-IT performed lookups into the collection database. If a match was found, the configuration of the Cobalt Strike team server was analysed. This configuration was then compared against the other Cobalt Strike team servers to check for similarities in for example domain names, version number, URL, and various other settings.

The adversary heavily relies on scheduled tasks for executing a batch-file (.bat) to perform their tasks. An example of the creation of such a scheduled task by the adversary:

schtasks /create /ru "SYSTEM" /tn "update" /tr "cmd /c c:\windows\temp\update.bat" /sc once /f /st 06:59:00The batch-files appear to be used to load the Cobalt Strike beacon, but also to perform discovery commands on the compromised system.

Persistence (TA0003)

The adversary loads the Cobalt Strike beacon in memory, without any persistence mechanisms on the compromised system. Once the system is rebooted, the beacon is gone. The adversary is still able to have persistent access by installing the beacon on systems with high uptimes, such as server. Besides using the Cobalt Strike beacon, the adversary also searches for VPN and firewall configs, possibly to function as a backup access into the network. We haven’t seen the adversary use those access methods after the first Cobalt Strike beacons were installed. Maybe because it was never necessary.

After the first bulk of data is exfiltrated, the persistent access into the victim’s network is periodically used by the adversary to check if new data of interest is available. They also create a copy of the NTDS.dit and SYSTEM-registry hive file for new credentials to crack.

Discovery (TA0007)

The adversary applied a wide range of discovery tactics. In the list below we have highlighted a few specific tools the adversary used for discovery purposes. You can find a summary of most of the commands used by the adversary to perform discovery at the end of this article.

Account discovery tool: PsLogList

Command used:

psloglist.exe -accepteula -x security -s -a <date>This command exports a text file with comma separated fields. The text files contain the contents of the Security Event log after the specified date.

Psloglist is part of the Sysinternals toolkit from Mark Russinovich (Microsoft). The tool was used by the adversary on various systems to write events from the Windows Security Event Log to a text file. A possible intent of the adversary could be to identify if privileged users are active on the systems. If such a privileged user was recently active on a server the actor executes Cobalt Strike’s built-in Mimikatz to dump its credentials or password hash.

Account discovery tool: NtdsAudit

Command used:

msadcs.exe "NTDS.dit" -s "SYSTEM" -p RecordedTV_pdmp.txt --users-csv RecordedTV_users.csvIt imports the specified Active Directory database NTDS.dit and registry file SYSTEM and exports the found password hashes into RecordedTV_pdump.txt and user details in RecordedTV_users.csv.

The NtdsAudit utility is an auditing tool for Active Directory databases. It allows the user to collect useful statistics related to accounts and passwords. The utility was found on various systems of a victim and matches the NtdsAudit.exe program file version v2.0.5 published on the GitHub project page.

Network service scanning

Command used:

get -b <start ip> -e <end ip> -p

get -b <start ip> -e <end ip>Get.exe appears to be a custom tool used to scan IP-ranges for HTTP service information. NCC Group and Fox-IT decompiled the tool for analysis. This showed the tool was written in the Python scripting language and packed into a Windows executable file. Though Fox-IT didn’t find any direct occurrences of the tool on the internet, the decompiled code showed strong similarities with the source code of a tool named GetHttpsInfo. GetHttpsInfo scans the internal network for HTTP & HTTPS services. The reconnaissance tool getHttpsInfo is able to discover HTTP servers within the range of a network.

The tool was shared on a Chinese forum around 2016.

Figure 1: Example of a download location for GetHttpsInfo.exe

Lateral movement (TA0008)

The adversary used the built-in lateral movement possibilities in Cobalt Strike. Cobalt Strike has various methods for deploying its beacons at newly compromised systems. We have seen the adversary using SMB, named pipes, PsExec, and WinRM. The adversary attempts to move to a domain controller as soon as possible after getting foothold into the victim’s network. They continue lateral movement and discovery in an attempt to identify the data of interest. This could be a webserver to carve PII from memory, or a fileserver to copy IP, as we have both observed.

At one customer, the data of interest was stored in a separate security zone. The adversary was able to find a dual homed system and compromise it. From there on they used it as a jump host into the higher security zone and started collecting the intellectual property stored on a file server in that zone.

In one event we saw the adversary compromise a Linux-system through SSH. The user account was possibly compromised on the Linux server by using credential stuffing or password spraying: Logfiles on the Linux-system show traces which can be attributed to a credential stuffing or password spraying attack.

Lateral tool transfer (T1570)

The adversary is applying living off the land techniques very well by incorporating default Windows tools in its arsenal. But not all tools used by the adversary are so called lolbins: As said before, they use Cobalt Strike. But they also rely on a custom tool for network scanning (get.exe), carving data from memory, compression of data, and exfiltrating data.

But first: How did they get the tools on the victim’s systems? The adversary copied those tools over SMB from compromised system to compromised system wherever they needed these tools. A few examples of commands we observed:

copy get.exe \\<ip>\c$\windows\temp\

copy msadc* \\<hostname>\c$\Progra~1\Common~1\System\msadc\

copy update.exe \\<ip>\c$\windows\temp\

move ak002.bat \\<ip>\c$\windows\temp\update.batCollection (TA0009)

In preparation of exfiltration of the data needed for their objective, the adversary collected the data from various sources within the victim’s network. As described before, the adversary collected data from an information repository, Microsoft SharePoint Online in this case. This document was exfiltrated and used to continue the intrusion via a company portal and VPN.

In all cases we’ve seen the adversary copying results of the discovery phase, like file- and directory lists from local systems, network shared drives, and file shares on remote systems. But email collection is also important for this adversary: with every intrusion we saw the mailbox of some users being copied, from both local and remote systems:

wmic /node:<ip> process call create "cmd /c copy c:\Users\<username>\<path>\backup.pst c:\windows\temp\backup.pst"

copy "i:\<path>\<username>\My Documents\<filename>.pst"

copy \\<hostname>\c$\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Outlook*.ostFiles and folders of interest are collected as well and staged for exfiltration.

The goal of targeting some victims appears to be to obtain Passenger Name Records (PNR). How this PNR data is obtained likely differs per victim, but we observed the usage of several custom DLL files used to continuously retrieve PNR data from memory of systems where such data is typically processed, such as flight booking servers.

The DLL’s used were side-loaded in memory on compromised systems. After placing the DLL in the appropriate directory, the actor would change the date and time stamps on the DLL files to blend in with the other legitimate files in the directory.

Adversaries aiming to exfiltrate large amounts of data will often use one or more systems or storage locations for intermittent storage of the collected data. This process is called staging and is one of the of the activities that NCC Group and Fox-IT has observed in the analysed C2 traffic.

We’ve seen the adversary staging data on a remote system or on the local system. Most of the times the data is compressed and copied at the same time. Only a handful of times the adversary copies the data first before compressing (archive collected data) and exfiltrating it. The adversary compresses and encrypts the data by using WinRAR from the command-line. The filename of the command-line executable for WinRAR is RAR.exe by default.

This activity group always uses a renamed version of rar.exe. We have observed the following filenames overlapping all intrusions:

- jucheck.exe

- RecordedTV.ms

- teredo.tmp

- update.exe

- msadcs1.exe

The adversary typically places the executables in the following folders:

- C:\Users\Public\Libraries\

- C:\Users\Public\Videos\

- C:\Windows\Temp\

The following four different variants of the use of rar.exe as update.exe we have observed:

update a -m5 -hp<password> <target_filename> <source>

update a -m5 -r -hp<password> <target_filename> <source>

update a -m5 -inul -hp<password> <target_filename> <source>

update a -m5 -r -inul -hp<password> <target_filename> <source>

The command lines parameters have the following effect:

- a = add to archive.

- m5 = use compression level 5.

- r = recurse subfolders.

- inul = suppress error messages.

- hp<password> = encrypt both file data and headers with password.

The used password, file extensions for the staged data differ per intrusion. We’ve seen the use of .css, .rar, .log.txt, and no extension for staged pieces of data.

After compromising a host with a Linux operating systems, data is also compressed. This time the adversary compresses the data as a gzipped tar-file: tar.gz. Sometimes no file extension is used, or the file extension is .il. Most of the times the files names are prepended with adsDL_ or contain the word “list”. The files are staged in the home folder of the compromised user account: /home/<username>/

Command and control (TA0011)

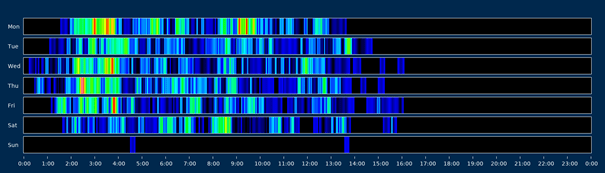

The adversary uses Cobalt Strike as framework to manage their compromised systems. We observed the use of Cobalt Strike’s C2 protocol encapsulated in DNS by the adversary in 2017 and 2018. They switched to C2 encapsulated in HTTPS in Q3 2019. An interesting observation is they made use of a cracked/patched trial version of Cobalt Strike. This is important to note because the functionalities of Cobalt Strike’s trial version are limited. More importantly: the trial version doesn’t support encryption of command and control traffic in cases where the protocol itself isn’t encrypted, such as DNS. In one intrusion we investigated, the victim had years of logging available of outgoing DNS-requests. The DNS-responses weren’t logged. This means that only the DNS C2 leaving the victim’s network was logged. We developed a Python script that decoded and combined most of the logged C2 communication into a human readable format. As the adversary used Cobalt Strike with DNS as command & control protocol, we were able to reconstruct more than two years of adversary activity. With all this activity data, it was possible for us to create some insight into the ‘office’-hours of this adversary. The activity took place six days a week, rarely on Sundays. The activity started on average at 02:36 UTC and ended rarely after 13:00 UTC. We observed some periods where we expected activity of the adversary, but almost none was observed. These periods match with the Chinese Golden Week holiday.

Figure 2: Heatmap of activity. Times on the X-axis are in UTC.

The adversary also changed their domains for command & control around the same time they switched C2 protocols. They used a subdomain under a regular parent domain with a .com TLD in 2017 and 2018, but they started using sub-domains under the parent domain appspot.com and azureedge.net in 2019. The parent domain appspot.com is a domain owned by Google, and part of Google’s App Engine platform as a service. Azureedge.net is a parent domain owned by Microsoft, and part of Microsoft’s Azure content delivery network.

Exfiltration (TA0010)

The adversary uses the command and control channel to exfiltrate small amounts of data. This is usually information containing account details. For large amounts of data, such as the mailboxes and network shares with intellectual property, they use something else.

Once the larger chunks of data are compressed, encrypted, and staged, the data is exfiltrated using a custom built tool. This tool exfiltrates specified files to cloud storage web services. The following cloud storage web services are supported by the malware:

- Dropbox

- Google Drive

- OneDrive

The actor specifies the following arguments when running the exfiltration tool:

- Name of the web service to be used

- Parameters used for the web service, such as a client ID and/or API key

- Path of the file to read and exfiltrate to the web service

We have observed the exfiltration tool in the following locations:

- C:\Windows\Temp\msadcs.exe

- C:\Windows\Temp\OneDrive.exe

Hashes of these files are listed at the end of this article.

Defense evasion (TA0005)

The adversary attempts to clean-up some of the traces from their intrusions. While we don’t know what was deleted and we were unable to recover, we did see some of their anti-forensics activity:

- Windows event logs clearing,

- File deletion,

- Timestomping

An overview of the observed commands can be found in the appendix.

For indicator removal on host: Timestomp the adversary uses a Windows version of the Linux touch command. This tool is included in the UnxUtils repository. This makes sure the used tools by the adversary blend in with the other files in the directory when shown in a timeline. Creating a timeline is a common thing to do for forensic analysts to get a chronological view of events on a system.

A number of our intrusions involved tips from an industry partner who was able to correlate some of their upstream activity.

Our threat intelligence analysts observed clear overlap between the various cases that NCC Group and Fox-IT worked in the threat’s infrastructure and capabilities, and as a result we assess with moderate confidence one activity group was carrying out the intrusions across the different type of victims.

Some overlap is very generic for a lot for a lot of groups, like the use of Cobalt Strike, or exfiltration to OneDrive. But the tool used for exfiltration to OneDrive is very specific for this adversary. The use of appspot and azureedge domains as well. The naming convention for their subdomains, tools and scripts overlap too. In summary:

The adversary: Working hours match with GMT+8.

Infrastructure: appspot.com and azureedge.net for C2 with a strong overlap in naming convention for subdomains and actual overlap in some subdomains between intrusions.

Capability: Password spraying/credential stuffing. Cobalt Strike. Copy NTDS.dit. Use scheduled tasks and batch files for automation. The use of LOLBins. WinRAR. Cloud exfil tool and exfil to OneDrive. Erasing Windows Event Logs, files and tasks. Overlap in filenames for tools, staged data, and folders.

Victim: Semiconductors and aviation industry.

We considered labelling them as two activity groups, as of the difference in victims between various intrusions. But all the other overlap is strong enough for us to consider it as one group right now. This group might have gotten a new customer interested in different data which changed the intent and victims of the adversary.

But most importantly: The largest overlap is in the top half of the pyramid of pain: domain names, host artifacts, tools, and TTPs. And these are the hardest for the adversary to change, and most effective for long-lasting detection!

Figure 3: Pyramid of pain by David J Bianco

Fox-IT and NCC Group found some very strong overlap between what we’ve seen in our intrusion, and what Cycraft describes in their APT Group Chimera report and Blackhat presentation. The bulk of the victims they describe are in different regions than we observed which is likely caused by field of view bias. SentinelOne also describes an attack and shares IOC’s that show strong overlap with the intrusions we investigated.

At this moment we believe based on the evidence observed that the various intrusions were performed by the same group. We can only report what we observed: first they stole intellectual property in the high tech sector, later they stole passenger name records (PNR) from airlines, both across geographical locations. Both types of stolen data are very useful for nation states.

Answering if this group has an advanced persistent threat (APT) technique, has some sort of state affiliation, or where they come from goes beyond the scope of this write-up. The threat intelligence and IOC’s we are sharing are intended to help discover and present intrusions by this and adversaries.

A word of thanks goes out to all the forensic experts, incident responders, and threat intelligence analysts who helped victims identifying and eradicating the adversary. And everybody from NCC Group and Fox-IT (part of NCC Group) for all the contributions to this article.

IOC

| Type | Data | Observed | Note |

| Binary MD5 | 133a159e86ff48c59e79e67a3b740c1e | – | get.exe (GetHttpsInfo) |

| Binary MD5 | 328ba584bd06c3083e3a66cb47779eac | – | psloglist.exe |

| Binary MD5 | 65cf35ddcb42c6ff5dc56d6259cc05f3 | – | update.exe (WinRAR) |

| Binary MD5 | 4d5440282b69453f4eb6232a1689dd4a | – | msadcs.exe (Cloud exfil tool) |

| Binary MD5 | 90508ff4d2fc7bc968636c716d84e6b4 | – | msadcs.exe (Cloud exfil tool) |

| Binary MD5 | c9b8cab697f23e6ee9b1096e312e8573 | – | jucheck.exe (WinRAR) |

| Binary MD5 | dd138a8bc1d4254fed9638989da38ab1 | – | msadcs.exe (NTDSAudit) |

| C2 domain | EuDbSyncUp[.]com | Q4 2017 – Q4 0218 | – |

| C2 domain | UsMobileSos[.]com | Q4 2017 – Q4 2018 | – |

| C2 domain | officeeuupdate.appspot[.]com | Q4 2017 – Q4 2018 | – |

| C2 domain | MsCupDb[.]com | Q4 2017 – Q4 2018 | – |

| C2 domain | officeeuropupd.appspot[.]com | Q3 2019 – Q1 2020 | – |

| C2 domain | platform-appses.appspot[.]com | Q4 2019 – Q1 2020 | – |

| C2 domain | watson-telemetry.azureedge[.]net | Q4 2019 – Q1 2020 | – |

| C2 domain | europe-s03213.appspot[.]com | 2019 | – |

| C2 domain | eustylejssync.appspot[.]com | 2019 | – |

| C2 domain | fsdafdsfdsaflkjkxvzcuifsad.azureedge[.]net | 2019 | – |

| C2 domain | ictsyncserver.appspot[.]com | 2019 | – |

| C2 domain | sowfksiw38f2aflwfif.azureedge[.]net | 2019 | – |

| Filename | fs_action*.bat | – | Task automation |

| Filename | fs_action*.ps1 | – | Task automation |

| Filename | update.bat | – | Task automation |

| Filename | update*.bat | – | Task automation |

| Filename | *dsinternals*.dll | – | Dsinternals lib files |

| Filename | get.exe | – | GetHttpsInfo |

| Filename | adsDL_<dir>.log | – | Staging data |

| Filename | group_membership.csv | – | SharpHound output |

| Filename | local_admins.csv | – | SharpHound output |

| Filename | msadcs.exe | – | Various tools |

| Filename | msadcs1.exe | – | WinRAR |

| Filename | OneDrive.exe | – | Cloud data exfil |

| Filename | sessions.csv | – | SharpHound output |

| Filename | RecordedTV.ms | – | WinRAR |

| Filename | RecordedTV_*.csv | – | Staging data |

| Filename | RecordedTV_*.ms | – | Staging data |

| Filename | RecordedTV_*.rar | – | Staging data |

| Filename | RecordedTV_*.txt | – | Staging data |

| Filename | teredo.tmp | – | WinRAR |

| Filename | update.exe | – | WinRAR |

| Filename | hsperfdata.sqm | – | Archive with tools |

| Filename | update*.log | – | Staging data |

| Hostname | DESKTOP-0FVJ37C | – | Origin of login to Exchange |

| IPv4 address | 47.75.0[.]147 | Q2 2019 | Password spray |

| IPv4 address | 59.47.4[.]27 | Q2 2019 | ADFS login |

| IPv4 address | 45.9.248[.]74 | Q2 2019 | Citrix login |

| IPv4 address | 172.111.210[.]53 | Q2 2019 | Citrix login |

| IPv4 address | 103.51.145[.]123 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 119.39.248[.]32 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 120.227.35[.]98 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 14.229.140[.]66 | 2019 | Mount the file-share |

| IPv4 address | 172.111.210[.]53 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 188.72.99[.]41 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 45.9.248[.]74 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 47.75.0[.]147 | 2019 | Password spray |

| IPv4 address | 5.254.112[.]226 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 5.254.64[.]234 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 59.47.4[.]27 | 2019 | Initial access |

| IPv4 address | 39.109.5[.]135 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 43.250.200[.]106 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 119.39.248[.]101 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 220.202.152[.]47 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 119.39.248[.]20 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 185.170.210[.]84 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 43.250.201[.]71 | Q3 2017 | VPN server login |

| IPv4 address | 23.236.77[.]94 | Q3 2017 | ADFS login |

| Path | C:\Code\NtdsAudit\src\NtdsAudit\obj\Release\ | – | NTDSAudit artifacts |

| Path | C:\Users\Public\Appdata\Local\ | – | Staging and tools |

| Path | C:\Users\Public\Appdata\Local\Microsoft\Windows\INetCache | – | Staging and tools |

| Path | C:\Users\Public\Libraries\ | – | Staging and tools |

| Path | C:\Users\Public\Videos\ | – | Staging and tools |

| Path | C:\Windows\Temp\ | – | Staging and tools |

| Path | C:\Windows\Temp\tmp | – | Staging and tools |

| URI in CS beacon | /externalscripts/jquery/jquery-3.3.1.min.js | Q3 2019 – Q1 2020 | – |

| URI in CS beacon | /externalscripts/jquery/jquery-3.3.2.min.js | Q2 2019 – Q3 2019 | – |

| URI in CS beacon | /jquery-3.3.2.slim.min.js | Q1 2020 | – |

| User-agent | Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko | – | Web VPN login |

| User-agent | Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko | – | Cobalt Strike beacon |

Observed discovery commands

| Technique | Command |

| Account discovery | net user |

| Account discovery | net user Administrator |

| Account discovery | net user /domain |

| Account discovery | dir \\<hostname>\c$\users |

| Account discovery | dsquery user -limit 0 -s <hostname> |

| Account discovery | psloglist.exe -accepteula -x security -s -a <current_date> |

| Account discovery | msadcs.exe “NTDS.dit” -s “SYSTEM” -p RecordedTV_pdmp.txt –users-csv RecordedTV_users.csv |

| Browser bookmark discovery | type \\<hostname>\c$\Users\<username>\Favorites\Links\Bookmarks bar\Imported From IE\*citrix* |

| Domain trust discovery | nltest /domain_trusts |

| File and directory discovery | dir \\<hostname>\c$\ |

| File and directory discovery | dir /o:d /x /s c:\ |

| File and directory discovery | dir /o:d /x \\<hostname>\<fileshare> |

| File and directory discovery | cacl <path to file> |

| Network service scanning | get -b <start ip> -e <end ip> -p |

| Network service scanning | get -b <start ip> -e <end ip> |

| Network share discovery | net share |

| Network share discovery | net view \\<hostname> |

| Permission groups discovery | net localgroup administrators |

| Process discovery | tasklist /v |findstr explorer |

| Process discovery | tasklist /v |findstr taskhost |

| Process discovery | tasklist /v |findstr 1716 |

| Process discovery | tasklist /v /s <hostname/ip> |

| Query registry | reg query \\<host>\HKU\<SID>\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Servers |

| Query registry | reg query \\<host>\HKU\<SID>\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings |

| Remote system discovery | type \\<host>\c$\Users\<username>\Favorites\Links\Bookmarks bar\Imported From IE\*citrix* |

| Remote system discovery | type \\<host>\<path>\Cookies\*ctx* |

| Remote system discovery | reg query \\<host>\HKU\<SID>\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Servers |

| Remote system discovery | dir /o:d /x \\<hostname>\c$\users\<username>\Favorites |

| Remote system discovery | net view \\hostname |

| Remote system discovery | dsquery server -limit 0 |

| System information discovery | fsutil fsinfo drives |

| System information discovery | systeminfo |

| System information discovery | vssadmin list shadows |

| System network configuration discovery | ipconfig |

| System network configuration discovery | ipconfig /all |

| System network configuration discovery | ping -n 1 -a <ip> |

| System network configuration discovery | ping -n 1 <hostname> |

| System network configuration discovery | tracert <ip> |

| System network configuration discovery | pathping <ip> |

| System network connections discovery | netstat -ano | findstr EST |

| System Owner/User Discovery | quser |

| System service discovery | net start |

| System service discovery | net use |

| System time discovery | time /t |

| System time discovery | net time \\<ip/hostname> |

Observed Defense evasion commands

Indicator Removal on Host: Clear Windows Event Logs

wevtutil cl "Windows PowerShell"

wevtutil cl application

wevtutil cl security

wevtutil cl setup

wevtutil cl systemIndicator Removal on Host: File Deletion

del /f/q *.csv *.bin

del /f/q *.exe

del /f/q *.exe *log.txt

del /f/q *.ost

del /f/q .rar update .txt

del /f/q \\c$\windows\temp*.txt

del /f/q \\c$\Progra~1\Common~1\System\msadc\msadcs.dmp

del /f/q msadcs*

del /f/q psloglist.exe

del /f/q update*

del /f/q update* .txt del /f/q update.rar

del /f/q update*rar

del /f/q update12321312.rarschtasks /delete /s /tn "update" /f

schtasks /delete /tn "update" /f

shred -n 123 -z -u .tar.gzMITRE ATT&CK references

| Name | Type | ID | More info |

| Initial Access | Tactic | TA0001 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0001/ |

| External Remote Services | Technique | T1133 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1133/ |

| Valid Accounts | Technique | T1078 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/ |

| Execution | Tactic | TA0002 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0002/ |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | Technique | T1059.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1059/001/ |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell | Technique | T1059.003 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1059/003/ |

| Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | Technique | T1053.005 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1053/005/ |

| System Services: Service Execution | Technique | T1569.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1569/002/ |

| Windows Management Instrumentation | Technique | T1047 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1047/ |

| Persistence | Tactic | TA0003 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0003/ |

| External Remote Services | Technique | T1133 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1133/ |

| Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Side-Loading | Technique | T1574.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1574/002/ |

| Valid Accounts | Technique | T1078 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/ |

| Privilege Escalation | Tactic | TA0004 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0004/ |

| Valid Accounts | Technique | T1078 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/ |

| Defense Evasion | Tactic | TA0005 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0005/ |

| Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | Technique | T1140 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1140/ |

| Indicator Removal on Host: Clear Windows Event Logs | Technique | T1070.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1070/001/ |

| Indicator Removal on Host: File Deletion | Technique | T1070.004 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1070/004/ |

| Indicator Removal on Host: Timestomp | Technique | T1070.006 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1070/006/ |

| Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Side-Loading | Technique | T1574.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1574/002/ |

| Masquerading: Rename System Utilities | Technique | T1036.003 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1036/003/ |

| Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location | Technique | T1036.005 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1036/005/ |

| Use Alternate Authentication Material: Pass the Hash | Technique | T1550.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1550/002/ |

| Valid Accounts | Technique | T1078 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/ |

| Credential Access | Tactic | TA0006 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0006/ |

| Brute Force: Password Spraying | Technique | T1110.003 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1110/003/ |

| Brute Force: Credential Stuffing | Technique | T1110.004 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1110/004/ |

| OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory | Technique | T1003.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1003/001/ |

| OS Credential Dumping: NTDS | Technique | T1003.003 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1003/003/ |

| Two-Factor Authentication Interception | Technique | T1111 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1111/ |

| Discovery | Tactic | TA0007 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0007/ |

| Account Discovery | Technique | T1087 | |

| Account Discovery: Local Account | Technique | T1087.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1087/001/ |

| Account Discovery: Domain Account | Technique | T1087.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1087/002/ |

| Browser Bookmark Discovery | Technique | T1217 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1217/ |

| Domain Trust Discovery | Technique | T1482 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1482/ |

| File and Directory Discovery | Technique | T1083 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1083 |

| Network Service Scanning | Technique | T1046 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1046 |

| Network Share Discovery | Technique | T1135 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1135 |

| Permission Groups Discovery | Technique | T1069 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1069 |

| Process Discovery | Technique | T1057 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1057 |

| Query Registry | Technique | T1012 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1012 |

| Remote System Discovery | Technique | T1018 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1018 |

| System Information Discovery | Technique | T1082 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1082 |

| System Network Configuration Discovery | Technique | T1016 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1016 |

| System Network Connections Discovery | Technique | T1049 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1049 |

| System Owner/User Discovery | Technique | T1033 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1033 |

| System Service Discovery | Technique | T1007 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1007 |

| System Time Discovery | Technique | T1124 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1124 |

| Lateral Movement | Tactic | TA0008 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0008/ |

| Lateral Tool Transfer | Technique | T1570 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1570/ |

| Remote Services: SMB/Windows Admin Shares | Technique | T1021.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1021/002/ |

| Remote Services: SSH | Technique | T1021.004 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1021/004/ |

| Remote Services: Windows Remote Management | Technique | T1021.006 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1021/006/ |

| Use Alternate Authentication Material: Pass the Hash | Technique | T1550.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1550/002/ |

| Collection | Tactic | TA0009 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0009/ |

| Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility | Technique | T1560.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1560/001/ |

| Automated Collection | Technique | T1119 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1119/ |

| Data from Information Repositories: SharePoint | Technique | T1213.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1213/002/ |

| Data from Local System | Technique | T1005 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1005/ |

| Data from Network Shared Drive | Technique | T1039 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1039/ |

| Data Staged: Local Data Staging | Technique | T1074.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1074/001/ |

| Data Staged: Remote Data Staging | Technique | T1074.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1074/002/ |

| Email Collection: Local Email Collection | Technique | T1114.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1114/001/ |

| Command and Control | Tactic | TA0011 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0011/ |

| Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | Technique | T1071.001 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1071/001/ |

| Application Layer Protocol: DNS | Technique | T1071.004 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1071/004/ |

| Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography | Technique | T1573.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1573/002/ |

| Protocol Tunneling | Technique | T1572 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1572/ |

| Exfiltration | Tactic | TA0010 | https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0010/ |

| Automated Exfiltration | Technique | T1020 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1020/ |

| Data Transfer Size Limits | Technique | T1030 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1030/ |

| Exfiltration Over C2 Channel | Technique | T1041 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1041/ |

| Exfiltration Over Web Service: Exfiltration to Cloud Storage | Technique | T1567.002 | https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1567/002/ |

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh