2021-8-6 15:57:0 Author: blog.orange.tw(查看原文) 阅读量:16 收藏

Author: Orange Tsai(@orange_8361)

P.S. This is a cross-post blog from DEVCORE

The series of A New Attack Surface on MS Exchange:

- A New Attack Surface on MS Exchange Part 1 - ProxyLogon!

- A New Attack Surface on MS Exchange Part 2 - ProxyOracle!

- A New Attack Surface on MS Exchange Part 3 - ProxyShell!

- A New Attack Surface on MS Exchange Part 4 - ProxyRelay!

Microsoft Exchange, as one of the most common email solutions in the world, has become part of the daily operation and security connection for governments and enterprises. This January, we reported a series of vulnerabilities of Exchange Server to Microsoft and named it as ProxyLogon . ProxyLogon might be the most severe and impactful vulnerability in the Exchange history ever. If you were paying attention to the industry news, you must have heard it.

While looking into ProxyLogon from the architectural level, we found it is not just a vulnerability, but an attack surface that is totally new and no one has ever mentioned before. This attack surface could lead the hackers or security researchers to more vulnerabilities. Therefore, we decided to focus on this attack surface and eventually found at least 8 vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities cover from server side, client side, and even crypto bugs. We chained these vulnerabilities into 3 attacks:

- ProxyLogon: The most well-known and impactful Exchange exploit chain

- ProxyOracle: The attack which could recover any password in plaintext format of Exchange users

- ProxyShell: The exploit chain we demonstrated at Pwn2Own 2021 to take over Exchange and earn $200,000 bounty

I would like to highlight that all vulnerabilities we unveiled here are logic bugs, which means they could be reproduced and exploited more easily than any memory corruption bugs. We have presented our research at Black Hat USA and DEFCON, and won the Best Server-Side bug of Pwnie Awards 2021. You can check our presentation materials here:

- ProxyLogon is Just the Tip of the Iceberg: A New Attack Surface on Microsoft Exchange Server! [Slides] [Video]

By understanding the basics of this new attack surface, you won’t be surprised why we can pop out 0days easily!

I would like to state that all the vulnerabilities mentioned have been reported via the responsible vulnerability disclosure process and patched by Microsoft. You could find more detail of the CVEs and the report timeline from the following table.

| Report Time | Name | CVE | Patch Time | CAS[1] | Reported By |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 05, 2021 | ProxyLogon | CVE-2021-26855 | Mar 02, 2021 | Yes | Orange Tsai, Volexity and MSTIC |

| Jan 05, 2021 | ProxyLogon | CVE-2021-27065 | Mar 02, 2021 | - | Orange Tsai, Volexity and MSTIC |

| Jan 17, 2021 | ProxyOracle | CVE-2021-31196 | Jul 13, 2021 | Yes | Orange Tsai |

| Jan 17, 2021 | ProxyOracle | CVE-2021-31195 | May 11, 2021 | - | Orange Tsai |

| Apr 02, 2021 | ProxyShell[2] | CVE-2021-34473 | Apr 13, 2021 | Yes | Orange Tsai working with ZDI |

| Apr 02, 2021 | ProxyShell[2] | CVE-2021-34523 | Apr 13, 2021 | Yes | Orange Tsai working with ZDI |

| Apr 02, 2021 | ProxyShell[2] | CVE-2021-31207 | May 11, 2021 | - | Orange Tsai working with ZDI |

| Jun 02, 2021 | - | - | - | Yes | Orange Tsai |

| Jun 02, 2021 | - | CVE-2021-33768 | Jul 13, 2021 | - | Orange Tsai and Dlive |

[1] Bugs relate to this new attack surface direclty

[2] Pwn2Own 2021 bugs

Why did Exchange Server become a hot topic? From my point of view, the whole ProxyLogon attack surface is actually located at an early stage of Exchange request processing. For instance, if the entrance of Exchange is 0, and 100 is the core business logic, ProxyLogon is somewhere around 10. Again, since the vulnerability is located at the beginning place, I believe anyone who has reviewed the security of Exchange carefully would spot the attack surface. This was also why I tweeted my worry about bug collision after reporting to Microsoft. The vulnerability was so impactful, yet it’s a simple one and located at such an early stage.

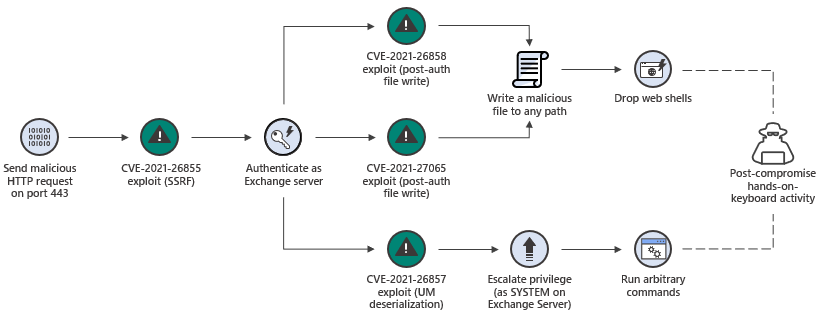

You all know what happened next, Volexity found that an APT group was leveraging the same SSRF ( CVE-2021-26855 ) to access users’ emails in early January 2021 and reported to Microsoft. Microsoft also released the urgent patches in March. From the public information released afterwards, we found that even though they used the same SSRF, the APT group was exploiting it in a very different way from us. We completed the ProxyLogon attack chain through CVE-2021-27065 , while the APT group used EWS and two unknown vulnerabilities in their attack. This has convinced us that there is a bug collision on the SSRF vulnerability.

Image from Microsoft Blog

Regarding the ProxyLogon PoC we reported to MSRC appeared in the wild in late February, we were as curious as everyone after eliminating the possibility of leakage from our side through a thorough investigation. With a clearer timeline appearing and more discussion occurring, it seems like this is not the first time that something like this happened to Microsoft . Maybe you would be interested in learning some interesting stories from here.

Mail server is a highly valuable asset that holds the most confidential secrets and corporate data. In other words, controlling a mail server means controlling the lifeline of a company. As the most common-use email solution, Exchange Server has been the top target for hackers for a long time. Based on our research, there are more than four hundred thousands Exchange Servers exposed on the Internet. Each server represents a company, and you can imagine how horrible it is while a severe vulnerability appeared in Exchange Server.

Normally, I will review the existing papers and bugs before starting a research. Among the whole Exchange history, is there any interesting case? Of course. Although most vulnerabilities are based on known attack vectors, such as the deserialization or bad input validation, there are still several bugs that are worth mentioning.

The most special

The most special one is the arsenal from Equation Group in 2017. It’s the only practical and public pre-auth RCE in the Exchange history. Unfortunately, the arsenal only works on an ancient Exchange Server 2003. If the arsenal leak happened earlier, it could end up with another nuclear-level crisis.

The most interesting

The most interesting one is CVE-2018-8581 disclosed by someone who cooperated with ZDI. Though it was simply an SSRF, with the feature, it could be combined with NTLM Relay, the attacker could turn a boring SSRF into something really fancy . For instance, it could directly control the whole Domain Controller through a low privilege account.

The most surprising

The most surprising one is CVE-2020-0688 , which was also disclosed by someone working with ZDI. The root cause of this bug is due to a hard-coded cryptographic key in Microsoft Exchange. With this hard-coded key, an attacker with low privilege can take over the whole Exchange Server. And as you can see, even in 2020, a silly, hard-coded cryptographic key could still be found in an essential software like Exchange. This indicated that Exchange is lacking security reviews, which also inspired me to dig more into the Exchange security.

Exchange is a very sophisticated application. Since 2000, Exchange has released a new version every 3 years. Whenever Exchange releases a new version, the architecture changes a lot and becomes different. The changes of architecture and iterations make it difficult to upgrade an Exchange Server. In order to ensure the compatibility between the new architecture and old ones, several design debts were incurred to Exchange Server and led to the new attack surface we found.

Where did we focus at Microsoft Exchange? We focused on the Client Access Service, CAS. CAS is a fundamental component of Exchange. Back to the version 2000/2003, CAS was an independent Frontend Server in charge of all the Frontend web rendering logics. After several renaming, integrating, and version differences, CAS has been downgraded to a service under the Mailbox Role. The official documentation from Microsoft indicates that:

Mailbox servers contain the Client Access services that accept client connections for all protocols. These frontend services are responsible for routing or proxying connections to the corresponding backend services on a Mailbox server

From the narrative you could realize the importance of CAS, and you could imagine how critical it is when bugs are found in such infrastructure. CAS was where we focused on, and where the attack surface appeared.

CAS is the fundamental component in charge of accepting all the connections from the client side, no matter if it’s HTTP, POP3, IMAP or SMTP, and proxies the connections to the corresponding Backend Service. As a Web Security researcher, I focused on the Web implementation of CAS.

The CAS web is built on Microsoft IIS. As you can see, there are two websites inside the IIS. The “Default Website” is the Frontend we mentioned before, and the “Exchange Backend” is where the business logic is. After looking

into the configuration carefully, we notice that the Frontend is binding with ports 80 and 443, and the Backend is listening on ports 81 and 444. All the ports are binding with

0.0.0.0, which means anyone could access the Frontend and Backend of Exchange directly. Wouldn’t it be dangerous? Please keep this question in mind and we will answer that later.

Exchange implements the logic of Frontend and Backend via IIS module. There are several modules in Frontend and Backend to complete different tasks, such as the filter, validation, and logging. The Frontend must contain a Proxy Module. The Proxy Module picks up the HTTP request from the client side and adds some internal settings, then forwards the request to the Backend. As for the Backend, all the applications include the Rehydration Module, which is in charge of parsing Frontend requests, populating the client information back, and continuing to process the business logic. Later we will be elaborating how Proxy Module and Rehydration Module work.

Frontend Proxy Module

Proxy Module chooses a handler based on the current ApplicationPath to process the HTTP request from the client side. For instance, visiting /EWS will use

EwsProxyRequestHandler, as for /OWA will trigger OwaProxyRequestHandler. All the handlers in Exchange inherit the class from

ProxyRequestHandler

and implement its core logic, such as how to deal with the HTTP request from the user, which URL from Backend to proxy to, and how to synchronize the information with the Backend. The class is also the most centric part of the

whole Proxy Module, we will separate

ProxyRequestHandler into 3 sections:

Frontend Request Section

The Request section will parse the HTTP request from the client and determine which cookie and header could be proxied to the Backend. Frontend and Backend relied on HTTP Headers to synchronize information and proxy internal status. Therefore, Exchange has defined a blacklist to avoid some internal Headers being misused.

HttpProxy\ProxyRequestHandler.cs

protected virtual bool ShouldCopyHeaderToServerRequest(string headerName) {

return !string.Equals(headerName, "X-CommonAccessToken", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& !string.Equals(headerName, "X-IsFromCafe", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& !string.Equals(headerName, "X-SourceCafeServer", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& !string.Equals(headerName, "msExchProxyUri", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& !string.Equals(headerName, "X-MSExchangeActivityCtx", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& !string.Equals(headerName, "return-client-request-id", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& !string.Equals(headerName, "X-Forwarded-For", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

&& (!headerName.StartsWith("X-Backend-Diag-", OrdinalIgnoreCase)

|| this.ClientRequest.GetHttpRequestBase().IsProbeRequest());

}

In the last stage of Request, Proxy Module will call the method AddProtocolSpecificHeadersToServerRequest

implemented by the handler to add the information to be communicated with the Backend in the HTTP header. This section will also serialize the information from the current login user and put it in a new HTTP header

X-CommonAccessToken, which will be forwarded to the Backend later.

For instance, If I log into Outlook Web Access (OWA) with the name Orange, the X-CommonAccessToken that Frontend proxy to Backend will be:

Frontend Proxy Section

The Proxy Section first uses the GetTargetBackendServerURL

method to calculate which Backend URL should the HTTP request be forwarded to. Then initialize a new HTTP Client request with the method CreateServerRequest.

HttpProxy\ProxyRequestHandler.cs

protected HttpWebRequest CreateServerRequest(Uri targetUrl) {

HttpWebRequest httpWebRequest = (HttpWebRequest)WebRequest.Create(targetUrl);

if (!HttpProxySettings.UseDefaultWebProxy.Value) {

httpWebRequest.Proxy = NullWebProxy.Instance;

}

httpWebRequest.ServicePoint.ConnectionLimit = HttpProxySettings.ServicePointConnectionLimit.Value;

httpWebRequest.Method = this.ClientRequest.HttpMethod;

httpWebRequest.Headers["X-FE-ClientIP"] = ClientEndpointResolver.GetClientIP(SharedHttpContextWrapper.GetWrapper(this.HttpContext));

httpWebRequest.Headers["X-Forwarded-For"] = ClientEndpointResolver.GetClientProxyChainIPs(SharedHttpContextWrapper.GetWrapper(this.HttpContext));

httpWebRequest.Headers["X-Forwarded-Port"] = ClientEndpointResolver.GetClientPort(SharedHttpContextWrapper.GetWrapper(this.HttpContext));

httpWebRequest.Headers["X-MS-EdgeIP"] = Utilities.GetEdgeServerIpAsProxyHeader(SharedHttpContextWrapper.GetWrapper(this.HttpContext).Request);

// ...

return httpWebRequest;

}

Exchange will also generate a Kerberos ticket via the HTTP Service-Class of the Backend and put it in the Authorization

header. This header is designed to prevent anonymous users from accessing the Backend directly. With the Kerberos Ticket, the Backend could validate the access from the Frontend.

HttpProxy\ProxyRequestHandler.cs

if (this.ProxyKerberosAuthentication) {

serverRequest.ConnectionGroupName = this.ClientRequest.UserHostAddress + ":" + GccUtils.GetClientPort(SharedHttpContextWrapper.GetWrapper(this.HttpContext));

} else if (this.AuthBehavior.AuthState == AuthState.BackEndFullAuth || this.

ShouldBackendRequestBeAnonymous() || (HttpProxySettings.TestBackEndSupportEnabled.Value

&& !string.IsNullOrEmpty(this.ClientRequest.Headers["TestBackEndUrl"]))) {

serverRequest.ConnectionGroupName = "Unauthenticated";

} else {

serverRequest.Headers["Authorization"] = KerberosUtilities.GenerateKerberosAuthHeader(

serverRequest.Address.Host, this.TraceContext,

ref this.authenticationContext, ref this.kerberosChallenge);

}

HttpProxy\KerberosUtilities.cs

internal static string GenerateKerberosAuthHeader(string host, int traceContext, ref AuthenticationContext authenticationContext, ref string kerberosChallenge) {

byte[] array = null;

byte[] bytes = null;

// ...

authenticationContext = new AuthenticationContext();

string text = "HTTP/" + host;

authenticationContext.InitializeForOutboundNegotiate(AuthenticationMechanism.Kerberos, text, null, null);

SecurityStatus securityStatus = authenticationContext.NegotiateSecurityContext(inputBuffer, out bytes);

// ...

string @string = Encoding.ASCII.GetString(bytes);

return "Negotiate " + @string;

}

Therefore, a Client request proxied to the Backend will be added with several HTTP Headers for internal use. The two most essential Headers are X-CommonAccessToken

, which indicates the mail users’ log in identity, and Kerberos Ticket, which represents legal access from the Frontend.

Frontend Response Section

The last is the section of Response. It receives the response from the Backend and decides which headers or cookies are allowed to be sent back to the Frontend.

Backend Rehydration Module

Now let’s move on and check how the Backend processes the request from the Frontend. The Backend first uses the method IsAuthenticated

to check whether the incoming request is authenticated. Then the Backend will verify whether the request is equipped with an extended right called ms-Exch-EPI-Token-Serialization

. With the default setting, only Exchange Machine Account would have such authorization. This is also why the Kerberos Ticket generated by the Frontend could pass the checkpoint but you can’t access the Backend directly with a

low authorized account.

After passing the check, Exchange will restore the login identity used in the Frontend, through deserializing the header X-CommonAccessToken

back to the original Access Token, and then put it in the httpContext object to progress to the business logic in the Backend.

Authentication\BackendRehydrationModule.cs

private void OnAuthenticateRequest(object source, EventArgs args) {

if (httpContext.Request.IsAuthenticated) {

this.ProcessRequest(httpContext);

}

}

private void ProcessRequest(HttpContext httpContext) {

CommonAccessToken token;

if (this.TryGetCommonAccessToken(httpContext, out token)) {

// ...

}

}

private bool TryGetCommonAccessToken(HttpContext httpContext, out CommonAccessToken token) {

string text = httpContext.Request.Headers["X-CommonAccessToken"];

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(text)) {

return false;

}

bool flag;

try {

flag = this.IsTokenSerializationAllowed(httpContext.User.Identity as WindowsIdentity);

} finally {

httpContext.Items["BEValidateCATRightsLatency"] = stopwatch.ElapsedMilliseconds - elapsedMilliseconds;

}

token = CommonAccessToken.Deserialize(text);

httpContext.Items["Item-CommonAccessToken"] = token;

//...

}

private bool IsTokenSerializationAllowed(WindowsIdentity windowsIdentity) {

flag2 = LocalServer.AllowsTokenSerializationBy(clientSecurityContext);

return flag2;

}

private static bool AllowsTokenSerializationBy(ClientSecurityContext clientContext) {

return LocalServer.HasExtendedRightOnServer(clientContext,

WellKnownGuid.TokenSerializationRightGuid); // ms-Exch-EPI-Token-Serialization

}

After a brief introduction to the architecture of CAS, we now realize that CAS is just a well-written HTTP Proxy (or Client), and we know that implementing Proxy isn’t easy. So I was wondering:

Could I use a single HTTP request to access different contexts in Frontend and Backend respectively to cause some confusion?

If we could do that, maaaaaybe I could bypass some Frontend restrictions to access arbitrary Backends and abuse some internal API. Or, we can confuse the context to leverage the inconsistency of the definition of dangerous HTTP headers between the Frontend and Backend to do further interesting attacks.

With these thoughts in mind, let’s start hunting!

The first exploit is the ProxyLogon. As introduced before, this may be the most severe vulnerability in the Exchange history ever. ProxyLogon is chained with 2 bugs:

- CVE-2021-26855 - Pre-auth SSRF leads to Authentication Bypass

- CVE-2021-27065 - Post-auth Arbitrary-File-Write leads to RCE

CVE-2021-26855 - Pre-auth SSRF

There are more than 20 handlers corresponding to different application paths in the Frontend. While reviewing the implementations, we found the method GetTargetBackEndServerUrl

, which is responsible for calculating the Backend URL in the static resource handler, assigns the Backend target by cookies directly.

Now you figure out how simple this vulnerability is after learning the architecture!

HttpProxy\ProxyRequestHandler.cs

protected virtual Uri GetTargetBackEndServerUrl() {

this.LogElapsedTime("E_TargetBEUrl");

Uri result;

try {

UrlAnchorMailbox urlAnchorMailbox = this.AnchoredRoutingTarget.AnchorMailbox as UrlAnchorMailbox;

if (urlAnchorMailbox != null) {

result = urlAnchorMailbox.Url;

} else {

UriBuilder clientUrlForProxy = this.GetClientUrlForProxy();

clientUrlForProxy.Scheme = Uri.UriSchemeHttps;

clientUrlForProxy.Host = this.AnchoredRoutingTarget.BackEndServer.Fqdn;

clientUrlForProxy.Port = 444;

if (this.AnchoredRoutingTarget.BackEndServer.Version < Server.E15MinVersion) {

this.ProxyToDownLevel = true;

RequestDetailsLoggerBase<RequestDetailsLogger>.SafeAppendGenericInfo(this.Logger, "ProxyToDownLevel", true);

clientUrlForProxy.Port = 443;

}

result = clientUrlForProxy.Uri;

}

}

finally {

this.LogElapsedTime("L_TargetBEUrl");

}

return result;

}

From the code snippet, you can see the property BackEndServer.Fqdn of AnchoredRoutingTarget is assigned from the cookie directly.

HttpProxy\OwaResourceProxyRequestHandler.cs

protected override AnchorMailbox ResolveAnchorMailbox() {

HttpCookie httpCookie = base.ClientRequest.Cookies["X-AnonResource-Backend"];

if (httpCookie != null) {

this.savedBackendServer = httpCookie.Value;

}

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(this.savedBackendServer)) {

base.Logger.Set(3, "X-AnonResource-Backend-Cookie");

if (ExTraceGlobals.VerboseTracer.IsTraceEnabled(1)) {

ExTraceGlobals.VerboseTracer.TraceDebug<HttpCookie, int>((long)this.GetHashCode(), "[OwaResourceProxyRequestHandler::ResolveAnchorMailbox]: AnonResourceBackend cookie used: {0}; context {1}.", httpCookie, base.TraceContext);

}

return new ServerInfoAnchorMailbox(BackEndServer.FromString(this.savedBackendServer), this);

}

return new AnonymousAnchorMailbox(this);

}

Though we can only control the Host part of the URL, but hang on, isn’t

manipulating a URL Parser

exactly what I am good at? Exchange builds the Backend URL by built-in UriBuilder. However, since C# didn’t verify the Host

, so we can enclose the whole URL with some special characters to access arbitrary servers and ports.

https://[foo]@example.com:443/path#]:444/owa/auth/x.js

So far we have a super SSRF that can control almost all the HTTP requests and get all the replies. The most impressive thing is that the Frontend of Exchange will generate a Kerberos Ticket for us, which means even when we are attacking a protected and domain-joined HTTP service, we can still hack with the authentication of Exchange Machine Account.

So, what is the root cause of this arbitrary Backend assignment? As mentioned, the Exchange Server changes its architecture while releasing new versions. It might have different functions in different versions even with the same component under the same name. Microsoft has put great effort into ensuring the architectural capability between new and old versions. This cookie is a quick solution and the design debt of Exchange making the Frontend in the new architecture could identify where the old Backend is.

CVE-2021-27065 - Post-auth Arbitrary-File-Write

Thanks to the super SSRF allowing us to access the Backend without restriction. The next is to find a RCE bug to chain together. Here we leverage a Backend internal API /proxyLogon.ecp

to become the admin. The API is also the reason why we called it ProxyLogon.

Because we leverage the Frontend handler of static resources to access the ECExchange Control Panel (ECP) Backend, the header msExchLogonMailbox

, which is a special HTTP header in the ECP Backend, will not be blocked by the Frontend. By leveraging this minor inconsistency, we can specify ourselves as the SYSTEM user and generate a valid ECP session with the internal

API.

With the inconsistency between the Frontend and Backend, we can access all the functions on ECP by Header forgery and internal Backend API abuse. Next, we have to find an RCE bug on the ECP interface to chain them together. The

ECP wraps the Exchange PowerShell commands as an abstract interface by

/ecp/DDI/DDIService.svc. The DDIService

defines several PowerShell executing pipelines by XAML so that it can be accessed by Web. While verifying the DDI implementation, we found the tag of WriteFileActivity did not check the file path properly and led to an

arbitrary-file-write.

DDIService\WriteFileActivity.cs

public override RunResult Run(DataRow input, DataTable dataTable, DataObjectStore store, Type codeBehind, Workflow.UpdateTableDelegate updateTableDelegate) {

DataRow dataRow = dataTable.Rows[0];

string value = (string)input[this.InputVariable];

string path = (string)input[this.OutputFileNameVariable];

RunResult runResult = new RunResult();

try {

runResult.ErrorOccur = true;

using (StreamWriter streamWriter = new StreamWriter(File.Open(path, FileMode.CreateNew)))

{

streamWriter.WriteLine(value);

}

runResult.ErrorOccur = false;

}

// ...

}

There are several paths to trigger the vulnerability of arbitrary-file-write. Here we use ResetOABVirtualDirectory.xaml as an example and write the result of

Set-OABVirtualDirectory to the webroot to be our Webshell.

Now we have a working pre-auth RCE exploit chain. An unauthenticated attacker can execute arbitrary commands on Microsoft Exchange Server through an exposed 443 port. Here is an demonstration video:

As the first blog of this series, ProxyLogon perfectly shows how severe this attack surface could be. We will have more examples to come. Stay tuned!

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh